Primary Source Guide: The Election 1860

Table of Contents:

Election Background

Candidates

Party Platforms

Campaigning

Election Day

Primary Sources

Further Reading

[Download as a PDF]

Teacher’s Guide

This guide is to assist students in formulating and understanding their own thoughts using primary sources.

Concepts Covered:

Primary sources can be letters, diaries, newspapers, documents, maps, photographs, charts, oral histories, cartoons, 3-D objects, and more. Examining these sources grant students a wide range of skills from conducting research to understanding and fact-checking complex texts. Primary source exploration can cover an array of Common Core State Standards including:

- Evaluating varied points of view

- Analyzing how specific word choices shape meaning

- Assessing the credibility of sources

- Conducting research projects based on focused questions

- Gathering evidence from literary and informational texts to support a claim

Language Arts Common Core Standards:

- Building knowledge through content-rich nonfiction

- Reading, writing, and speaking grounded in evidence from text, both literary and informational

- Regular practice with complex text and its academic language

The National Council for the Social Studies C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards:

- Understanding historical perspectives and how those perspectives shaped historical themes and events

- Identifying, summarizing, comparing, and analyzing historical sources

- Finding helpful sources that can support an overarching argument

- Gathering and evaluating multiple sources to build context

The Election Background of 1860 Background

The presidential election of 1860 took place in a time of national crisis. The presidential platforms in the election of 1860 covered topics such as a national tariff, a transcontinental railroad, the Homestead Act, and the principal issue, slavery. This election featured four parties running for election. The Republican party, which had fielded its first presidential candidate in 1856, was formed after the collapse of the Whig Party in 1854. The Democratic Party, unable to agree on the topic of slavery, split into northern and southern factions. The last party, the Constitutional Union party, was formed in 1859 by conservatives in Washington, D.C., who wanted to ignore the topic of slavery entirely.

Meet the Candidates

Four candidates were nominated for president in the election of 1860: Abraham Lincoln, John Breckenridge, Stephen Douglas, and John Bell.

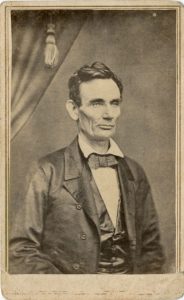

Abraham Lincoln

The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) was born in a one-room log cabin in Hodgenville, Kentucky. His father moved the family to Spencer County, Indiana in 1816. In 1830, the family once again moved, this time to Illinois. Before becoming a legislator in 1834, Lincoln worked odd jobs: store clerk, surveyor, and postmaster. He also served as a captain of the 31st Regiment of Sangamon County, Illinois during the Black Hawk War of 1832.

During his first term in the Illinois House of Representatives, a colleague encouraged Lincoln to take up the law as a career. Lincoln did, and became an entirely self-taught lawyer. In Springfield, Illinois, he practiced law and launched his political career. Lincoln served a short stint in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. In 1858, Lincoln and Stephen Douglas held seven formal public debates in hopes to win one of the two Illinois Senate seats in the U.S. Congress. While Lincoln was defeated by Douglas for the seat, his ability as an orator helped him gain support from the public and increased national recognition.

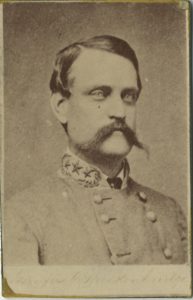

John C. Breckinridge

The Southern Democrats nominated John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875). Breckinridge was born in Lexington, Kentucky, and was a graduate of Centre College and later Transylvania Law School in 1845. Breckinridge was a lawyer, politician, and served as a major in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848).

Breckinridge was a strong advocate for states’ rights. However, while he was personally opposed to slavery and backed the colonization movement, or the movement to free the slaves and resettle them in Africa, he supported the legality of slavery and its expansion into the territories. In 1856 Breckinridge was nominated as James Buchanan’s vice-president. The two won the election, making Breckinridge the youngest vice-president in U.S. history. When the public opinion of President Buchanan began faltering, Breckinridge’s began to blossom, and his popularity rose among southern voters.

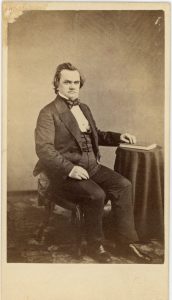

Stephen A. Douglas

The Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861). Douglas was born in Brandon, Vermont, during the war of 1812 and grew up on his uncle’s farm. Douglas studied law in New York and began his career in politics in Jacksonville, Illinois. Over time Douglas became known for his oratory skills and his ability to write and create bills.

Douglas supported the transcontinental railroad, a homestead policy, the expansion of U.S. territory, and the formal organization of U.S. territories. Douglas wrote his most infamous piece of legislation, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, in 1854, which permitted the expansion of slavery into the western territories under an idea called popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty, or the right for new states and territories to vote on whether to include or exclude slavery within their borders. was not just the core of the Kansas-Nebraska Act but Douglas’ answer to the slavery question. Support for him among his party waned, as many saw Douglas as a Democrat who promoted and/or protected Southern interests at the cost of Northern interests.

Kansas had applied for statehood under the Lecompton Constitution, which directly went against popular sovereignty to permit slavery despite the will of the majority of voters. President Buchanan supported this state constitution, but Douglas could not. He broke off from the Democratic Party and joined the Republicans to block the passage of the statehood bill. In the eyes of the Southern Democrats Douglas betrayed them and lost all support.

John Bell

John Bell (1797-1869) was nominated by the newly formed Constitutional Union Party. Bell was born in Nashville, Tennessee, and attended the University of Nashville. He was a lawyer, politician, and planter. Bell was a Representative in the U.S. Congress from 1827 to 1841 and served as Speaker of the House from 1834 to 1835. Originally a Democrat, he switched affiliation and joined the Whig Party. During his time in the House, he served as chair for the Committee on Indian Affairs and the Committee on the Judiciary.

After deciding not to run for reelection for the House in 1841, Bell accepted a place in President William Henry Harrison’s Cabinet as Secretary of War. He resigned only a few months after the death of Harrison in 1841 and returned to Congress, serving as U.S. Senator from Tennessee from 1847 to 1859.

In 1859 John Crittenden of Kentucky and 50 other border state and conservative congressmen formed the Constitutional Union Party. The Party’s platform hoped to rally support for the Union and the Constitution without regard to sectional issues. Their slogan was “The Union as it is, the Constitution as it is.” The party nominated John Bell for president and attempted to ignore the slavery issue entirely, in hopes of winning the support of border state voters.

Party Platforms

Republican Party

The Republican Party’s platform centered on its moral objection to slavery. Lincoln and the party pledged to keep slavery out of the territories but vowed to keep slavery untouched where it already existed.

Northern Democratic Party

The Northern Democratic Party’s platform was based on “popular sovereignty,” or the right for new states and territories to vote on whether to include or exclude slavery within their borders.

Southern Democratic Party

The Southern Democratic Party’s platform opted for a federal slave code, which would allow anyone to own slaves within all federal territories.

Constitutional Union Party

The Constitutional Union platform pledged to ignore the topic of slavery as was done in the past in hopes of keeping the country united and preventing Southern rebellion.

Campaigning

During the 1800s candidates depended on their supporters to get their names and platforms before voters and to build voter enthusiasm for elections. If a candidate campaigned publicly on their own behalf, voters would see them as undignified and overly ambitious.

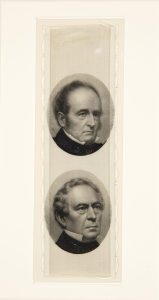

Publication of campaign newspapers, songsters, tokens, buttons, ribbons, and posters were created and distributed during the campaign season. Supporters held rallies, marched in parades, and gave speeches to appeal to voters. Another way the voters could “meet” their political party’s presidential candidate was by reading candidate biographies written and published expressly for the presidential campaign. These biographies were frequently issued as pamphlets bound in paper wrappers. Most included a woodcut or engraving of the candidate, either on the cover or opposite the title page.

The campaign had another, less visible side. Privately from their offices, candidates worked for their election by courting potential supporters and keeping tabs on the activities of their opponents. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, wrote to Indiana politician Richard W. Thompson (1809-1900), a former Whig and Know-Nothing party member who backed Constitutional Union Party candidate John Bell until August 1860 when he transferred his support to Lincoln.

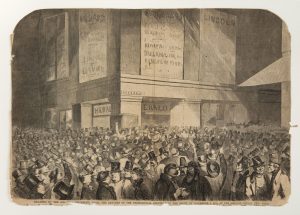

Election Day

On November 6, 1860, voters went to the ballot box to cast their votes in droves. Lincoln won the Electoral College by a landslide. Since the North had more voters, the majority of the Electoral College was controlled by the Northern states. Lincoln didn’t win a single vote from a Southern state. The election of 1860 established the Democratic and Republican parties as the dominant political parties in the United States. It also was the tipping point for Southern representatives to vote to secede from the Union in order to preserve slavery. Within a few weeks, the newly-formed insurrectionist Confederate States of America fired on Fort Sumter and started the Civil War.

Primary Sources:

Click each primary source type to view items.

Manuscripts, Speeches, & Documents

Further Reading

Teen Resources

The Election of 1860: A Nation Divides on the Eve of War by Jessica Gunderson

The Election of 1860 and the Administration of Abraham Lincoln by Arthur Meier

Schlesinger

Adult Resources

Lincoln and the Election of 1860 by Michael Green

The Election of 1860: “A Campaign Fraught with Consequences” by Michael Holt

The Election of 1860: Reconsidered by James Fuller

Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election of 1860

by Douglas Egerton

Lincoln’s Campaign Biographies by Thomas A. Horrocks