Where and How Lincoln Composed His Main Works

Where and How Lincoln Composed His Main Works

By D. Leigh Henson

Lincoln’s numerous compositions encompass a remarkable range of purposes and genre, constituting a major field of study for academics in such diverse fields as history, political science, rhetoric, literature, and language. Recently, John Channing Briggs, Douglas L. Wilson, and Fred Kaplan have added to our knowledge of Abraham Lincoln’s skillful composition, especially his writing process and techniques of style.[1] Scholars note that Lincoln was particularly careful in revising for the publication he often sought for his pre-presidential political speeches. Other aspects of Lincoln the writer invite consideration. This essay identifies places where Lincoln worked at writing and discusses a key facet of his composing process—his use of exploratory “fragments” and “notes.”

Eyewitnesses provide insight into where and how Lincoln as a politician and president wrote, but there are not many who put their observations in writing, with only four cited in this study: William H. Herndon, his third law partner and political advisor; Henry B. Rankin, who claimed he studied law in the Lincoln-Herndon law office; Noah Brooks, Lincoln’s White House confidant designated as his secretary for his second presidential term; and Francis B. Carpenter, the artist who painted the famous First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln. John G. Nicolay and John M. Hay’s ten-volume Lincoln biography includes critical commentary on Lincoln’s political rhetoric and presidential eloquence, especially his use of language. These biographers noted that Lincoln’s compositional powers grew, but they do not provide insight into that process, nor do they describe Lincoln as he was writing.

Lincoln’s career as a lawyer required writing standard documents and private letters, while his political career involved composing private and public letters, editorials, campaign announcements, handbills, stump speeches for his own campaigns and for presidential campaigns (Whigs in 1836 and 1840, Republicans in 1856), debate speeches, addresses in the Illinois legislature and Congress, legislative resolutions, and remarks. His interest in politics also led him to write and deliver eulogies for President Zachary Taylor and Congressman Henry Clay. Even Lincoln’s lectures had implicit political purposes. His political compositions were vital to his rise to the presidency, and passages in some of them foreshadowed the statesmanship and literary distinction of his inaugural addresses, Gettysburg Address, and last speech.

Lincoln began writing in childhood, and he developed the habit of writing whenever and wherever he wanted to capture his ideas. Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, who could read but not write, probably began to teach him to read before the family moved from Kentucky to Indiana when he was seven. Receiving scant formal education in Indiana, Lincoln there demonstrated his life-long commitment to self-education. According to his stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, the boy Lincoln copied passages of particular interest from his reading, read them aloud, and kept them in a scrapbook, but the only surviving pages of Lincoln’s hand from the 1820s are from his “cyphering book,” which includes his first attempt at verse. When he lacked paper, he wrote on “boards.” Eventually the young Lincoln in Indiana even composed essays on such subjects as cruelty to animals and temperance.[2]

Some of Lincoln’s Indiana compositions were satirical. The only surviving example is “The Chronicles of Reuben,” a story saved through oral history. Lincoln apparently created this story as revenge against a family that failed to invite the Lincolns to a double wedding. Lincoln’s sarcasm refers to the wedding night in which the grooms, brothers in the offending family, inadvertently go to bed with the wrong brides. Additionally, during his time in New Salem (1832–1837), Lincoln wrote legal materials for acquaintances in their places of business and homes, and perhaps in the stores where he clerked.

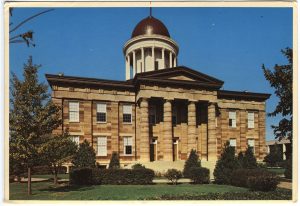

In his law offices Lincoln worked on political speeches and probably other compositions besides legal documents and related correspondence. During an 1867 interview in the Lincoln-Herndon law office, Herndon told a newspaper reporter, “On this very table . . . on this very corner [of it] Lincoln wrote ‘A House Divided Against Itself’” [1858 House Divided speech].[3] Lincoln’s Springfield law offices were in four locations. The first was in Hoffman’s Row one block north of the Capitol on Fifth Street during his partnership with John T. Stuart (1837–1841). The second was on the opposite side of the street in partnership with Stephen T. Logan (1841–1843) before they moved to the third floor of the Tinsley Building on Adams Street on the south side of the Capitol square (1843–1844). Lincoln and Herndon also had their office on the third floor of the Tinsley Building (1844–1857).[4] Lincoln probably worked on his 1854 Peoria address there and surely in the Capitol’s law library as he did research there for that speech. Lincoln probably worked on his 1857 Dred Scott speech in his Tinsley Building office and/or in the second-floor office at the back of a building on the west side of the Capitol square, where Lincoln and Herndon moved in 1857.[5]

Herndon observed Lincoln as a researcher and writer/speaker longer than anyone else. Herndon noted that Lincoln’s concern for public welfare and opinion in accomplishing public policy was evident early in his political career. Reflecting on Lincoln’s 1836 announcement to run for reelection to the Illinois legislature, Herndon wrote, “He classed universal suffrage, temperance, and slavery” as matters that “‘must first find lodgement with the most enlightened souls who stamp them with their approval. In God’s own time they will be organized into law and thus woven into the fabric of our institutions.’”[6] Lincoln’s main political compositions apply direct or indirect moral argumentation.

Herndon’s account of Lincoln’s House Divided speech focused on his composing process:

He had been all along led to expect it [1858 nomination as the Illinois Republican candidate for the US Senate], and with that in view had been earnestly and quietly at work preparing a speech in acknowledgment of the honor about to be conferred on him. This speech he wrote on stray envelopes and scraps of paper, as ideas suggested themselves, putting them into that miscellaneous and convenient receptacle, his hat. As the convention drew near he copied the whole on connected sheets, carefully revising every line and sentence, and fastened them together, for reference during the delivery of the speech, and for publication. The former precaution, however, was unnecessary, for he had studied and read over what he had written so long and carefully that he was able to deliver it without the least hesitation or difficulty.[7]

The composing process described here surely reflects Lincoln’s characteristic preparation of important political speeches and other writings in the critical two years leading to his run for the presidency.

Herndon also reported that Lincoln solicited the opinions of “a dozen or so of his friends” on the House Divided speech before it was given, with some of them predicting that speech would alienate Democrats who had newly joined the Republican cause. Herndon wrote that Lincoln rejected that criticism with the assertion that the time is exactly right for such a speech and that he is willing to risk going down with its truths—its “advocacy of what is just and right.”

Herndon noted that Lincoln was a self-confident writer: “He often asked as to the use of a word or the turn of a sentence, but if I volunteered to recommend or even suggest a change of language which involved a change of sentiment [meaning] I found him the most inflexible man I have ever seen.” Herndon allegedly told Lincoln that giving the House Divided speech would make him president, and critics have faulted that claim as gratuitous. Herndon says that when Lincoln returned to Springfield during the 1858 Senate race he “consulted with friends.”

Herndon’s assistance to Lincoln during that campaign indicates the importance of research in the candidate’s composing process during his political rise:

He kept me busy hunting up old speeches and gathering facts and statistics at the State Library [in the Capitol]. I made liberal clippings bearing in any way on the questions of the hour from every newspaper I happened to see, and kept him supplied with them, and on one or two occasions, to answer to letters and telegrams. I sent books forward to him. He had a little leather bound book, fastened in front with a clasp, in which he and I both kept inserting newspaper slips and newspaper comments until the canvass opened.[8]

Herndon’s Lincoln biography includes critical commentary on Lincoln and Dan Stone’s 1837 protest in the Illinois Legislature against slavery, the 1848 speech in Congress on internal improvements, the 1854 Peoria speech, Lincoln’s 1858 debate speeches in general, his 1859 Ohio and Kansas speeches, and the 1860 Cooper Union address, but those commentaries offer no further insight into Lincoln’s composing/revising process.

Lincoln worked on speeches in the second Lincoln-Herndon law office, on the west side of the Capitol square, surely during his famous 1858 US Senate race against Stephen A. Douglas. Henry B. Rankin wrote that he saw Lincoln working in his office on the 1860 Cooper Union address—sometimes cited as the speech that made him president. Rankin reported that Lincoln’s preparation for that speech involved spending considerable time on historical research in the State Library (in the Capitol) and that Lincoln discussed his findings with Herndon and Newton Bateman (then the Illinois Superintendent of Public Instruction).[9]

Seeking solitude to work on his First Inaugural address, Lincoln got permission from Clark M. Smith, his brother-in-law, to seclude himself in a small, third-floor room of his general store on the south side of the Capitol square, with just a chair, desk, and the four publications he asked Herndon to collect for him, which Herndon identified as “Henry Clay’s great speech delivered in 1850, Andrew Jackson’s proclamation against Nullification, the Constitution,” and [later] “Webster’s reply to Hayne, a speech which he read when he lived at New Salem.”[10]

Lincoln’s bedroom in Springfield included a desk, and he undoubtedly found late-night solitude there conducive to writing. It is uncertain whether Lincoln’s White House bedroom had a desk. In response to my email inquiry of April 29, 2022, The White House Historical Association replied, “It does not seem that Lincoln’s White House bedroom had a desk, though there are very few mentions of the room’s furnishings.”

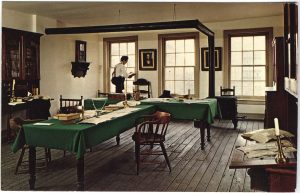

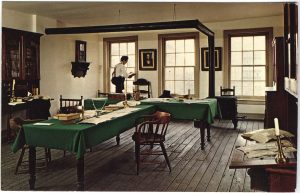

C.K. Stellwagen’s 1866 drawing of Lincoln’s White House office, on the second floor, sometimes called the Cabinet Room, shows the furniture that Lincoln used for writing. There were two desks besides the long table used for Cabinet meetings as depicted in Francis B. Carpenter’s painting First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln, which hangs in the US Capitol. Besides writing on that table, Lincoln could have written on a large desk with a tall back case and elevated slanting work surface, and, more conveniently, at a smaller desk a few feet in front of it. The top of the smaller desk is long but not wide, with a low back case. It appears to be particularly designed for writing and was located just beyond the end of the Cabinet Room’s long table toward the wall with two windows looking toward the Washington Monument and Potomac River. Most likely, this smaller desk is the one that Carpenter’s Six Months at the White House refers to several times as Lincoln’s desk, including twice as his “writing desk.”[11] David S. Reynolds notes that Lincoln’s office had “rickety furniture,” including “his old desk under a window overlooking the Potomac; a large wooden table for cabinet meetings in the center of the room.”[12]

Stellwagen’s drawing of the Cabinet Room shows an armchair between the large and small desks, near the wall with two windows, and Lincoln sometimes wrote while sitting in an armchair. In describing Lincoln’s work on a Congressional message, Noah Brooks wrote: “The president’s message was first written with pencil on stiff sheets of white pasteboard, or boxboard, a good supply of which he kept by him.

These sheets, five or six inches wide, could be laid on the writer’s knee, as he sat comfortably in his armchair, in his favorite position, with his legs crossed.”[13] For reference, President Lincoln kept files on the important people he corresponded with: “In his office in the public wing of the White House was a little cabinet, the interior divided into pigeonholes. The pigeonholes were lettered in alphabetical order, but a few were devoted to individuals. Horace Greeley, I remember, had a pigeonhole by himself; so did each of several generals who wrote often to him.”[14]

According to the Mr. Lincoln’s White House website, he also wrote in the War Department’s telegraph office: “The office gave Mr. Lincoln an opportunity to write and think in peace as he waited for telegrams to arrive and be deciphered.”[15] He allegedly worked on the Emancipation Proclamation there.[16]

Lincoln sometimes used private writing to express his feelings and rehearse arguments and language. In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, the titles of 111 writings contain the words “fragments” or “notes,” and sometimes the editors refer to these pieces as “scraps.” Thirty-nine of the fragments/notes date to before Lincoln’s 1860 presidential election.

In Lincoln in Private, Ronald C. White describes Lincoln’s fragments and notes as “private reflections” and “highly personal scraps of writings.”[17] White does not mention that Lincoln’s fragments/notes are not about such personal concerns as his relationship with his parents, stepmother, marriage, or fatherhood. White explains that Lincoln composed these pieces so that his “best thoughts” would “not escape him,” referring to these pieces as “building blocks that can help us reconstruct Lincoln’s thought processes as he approached history-altering decisions,” and that he likely composed many others.[18] White’s book focuses on just twelve of the 111 fragments/notes that he says “reveal new and interesting aspects about Lincoln” that White’s previous thirty-plus years of Lincoln study had not taught him.

White observes that “almost every surviving Lincoln fragment/note begins with a challenge” and that “although a few of the notes appear to be part of a first draft or preparation for a more polished public speech, the large majority are reflections and analyses that did not reappear anywhere else.”[19] The titles and dates, however, for sixteen of the first thirty-nine fragments or notes (41%) specify they were prepared for speeches or debates (sometimes at named places) and a law lecture. The following survey discusses examples of the most substantial fragments/notes relating to possible or actual speech or lecture preparation.

Lincoln drafted a 3,600-word Fragment on the Tariff (1847) in preparing to enter Congress because Whigs had favored a tariff, but he never delivered a speech on that subject. Instead, his congressional speeches were about other subjects of interest to Whigs that eclipsed the tariff: the Mexican War, internal improvements, and the 1848 presidential race. It is uncertain whether or how Lincoln may have publicly or privately used some of his 250-word Fragment: What General Taylor Ought to Say (1848). The 715-word Notes: Fragment Law Lecture (July 1, 1850?), urged students of the law to practice business “diligence,” seek settlements out of court, prepare thoroughly, and learn to speak effectively, but Lincoln never gave such a lecture or published on practicing law. The Complete Works includes two fragments on government, with a combined word count of 427. Those fragments are arbitrarily dated to 1854, and Lincoln may have intended them for a lecture.

Dated arbitrarily to April 1, 1854, are two fragments on slavery, 400 words combined, from before Lincoln delivered his October Peoria address. That speech launched his second political career and is widely recognized as presenting his foundational antislavery arguments, including his central position grounded in the equality language of the Declaration of Independence. One of Lincoln’s fragments on slavery expresses that position: “Most governments have been based, practically, on the denial of equal rights of men, as I have, in part, stated them; ours began by affirming those rights. . . We proposed to give all a chance; and we expected the weak to grow stronger, the ignorant, wiser; and all better, and happier together.”[20]

The other fragment on slavery, noted Roy P. Basler lead editor of The Collected Works, may belong to a later period than 1854. That fragment contains a logical train of thought suggesting Lincoln’s mind at work on slavery when he contended with Douglas over slavery and race during the 1858 Senate campaign: “If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?—You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.”[21] None of Lincoln’s subsequent speeches or other compositions employ this exact language, but several speeches criticize the indifference to enslavement based racial superiority—one of Douglas’s main positions.

Possibly written as the first Republican presidential campaign began, the Fragment on Sectionalism (c. July 23, 1856), is a 1,762-word analysis of Northern and Southern political, economic, and moral perspectives on slavery extension and whether proponents or opponents of it are “more sectional than the other.” Lincoln notes that Southerners are driven by an economic interest in slavery, while “moral principle . . . unites us of the North.” He questions whether the side without moral concern for slavery extension should “really think that by [the] right surrendering to wrong, the hopes of our Constitution, our Union, and our liberties, can possibly be bettered?”

In 1856, as Lincoln campaigned for the Republican presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, he condemned the Southern charge that the Republican Party was sectional and disunionist, arguing for free labor and denying that the Southern cause would prevail. After his party’s defeat, Lincoln urged its members to keep working on shaping public opinion to embrace the principle that “all men are created equal.”[22]

The alleged dates of twelve fragments/notes coincide with the 1858 Senate race. Three concern a stump speech Lincoln made at Edwardsville on May 18 and show that he was anticipating oppositional positions he would probably encounter in the campaign, including sectionalism, the threat of slavery extension, and Douglas’s regard for it. Those fragments/notes rehearse his responses to rival positions. The May speech includes language Lincoln would use in the House Divided speech, June 16. Among the twelve fragments/notes are three concerning slavery and several whose titles say they were in preparation for speeches in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Given the volume of the twelve fragments/notes, the following discussion concerns just two more of them; they are chosen for the important insights they afford into Lincoln’s campaign rhetoric.

The first is a 2,450-word Fragment of a Speech (c. December 28, 1857). Like other fragments, the date is questionable. Basler observed that in this fragment “key reference and much of the argument in the identical language of the House Divided speech was derived from an earlier speech fragment, or that the fragment was in part actually a preliminary draft of that speech.”[23] The 2,450-word fragment features the rhetorical qualities characteristic of the speeches Lincoln carefully crafted as he rose to political prominence in 1858: the speech develops logically through a problem-solution organization, ending with a cogent call to action. The language is direct and precise.

The fragment starts with an explanation of the problem that Douglas’s position and policy on slavery pose for Republicans. Lincoln admonished Republicans not to align with Douglas based strictly on his opposition to the proslavery Lecompton Constitution, for such an alignment would make them captive to the Democratic Party, whose other policies are decidedly proslavery. Maintaining that Douglas has done nothing to “get a free-state majority into Kansas,” Lincoln argued that Douglas’s indifference as to whether slavery “is voted down or voted up” is contradictory to Republicans’ position that slavery is morally wrong. Lincoln reminded Republicans that Douglas accuses them of sectionalism.

Lincoln began the second half of the fragment by asking and answering the question of “what ought Republicans do?” He averred that Republicans should support Douglas if he succeeds in “securing a fair vote to the people of Kansas, without contrivance.” Lincoln reiterated that Republicans in Congress “ought to keep slavery out of a territory, up to the time of its forming a state constitution.” He argues that the purpose of Douglas’s 1854 Nebraska bill was to begin shaping public opinion to be indifferent to the immorality of slavery and that presently there is more “angry agitation of this subject, both in and out of Congress, than ever before.” Lincoln then exclaimed: “A house divided against itself cannot stand” and proceeded by stating the same position and language he would use in the House Divided speech—that he did not “expect the Union to be dissolved,” but the tendency is toward extending slavery even into free states. Lincoln gave a call to action with loaded language: the solution of giving “victory to the right [is] not bloody bullets, but peaceful ballots,” as provided for in the “good old Constitution.”

Basler observed that the 2,860-word Fragment: Notes for Speeches (c. August 21, 1858), pertains to Lincoln’s single speech in the first of the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, at Ottawa, and two stump speeches that Lincoln gave between the first and second debates. Much of this fragment rehearses Lincoln’s subsequent defense of the Democratic proslavery conspiracy accusation from the House Divided speech that he would make in the second and sixth debates. He also repeated the view that the Dred Scott decision was not settled law, as he also said in his Speech at Springfield, June 26, 1857, and would maintain during the 1858 Senate campaign.

Douglas sometimes willfully misrepresented Lincoln’s rhetoric, and the fragment dated c. August 21, 1858, expresses his frustration with that demagoguery:

He [Douglas] takes issues I have not tendered. In good faith I try to set him right. If he really has misunderstood my meaning, I give him language that can no longer be misunderstood. He will have none of it. At Bloomington, six days later [July 17, 1858], he speaks again, and perverts me even worse than before. He seems to have grown confident and jubilant, in the belief that he has entirely diverted me from my purpose of fixing a conspiracy upon him and his co-workers [Lincoln’s allegation that Democratic Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, and Douglas collaborated to spread slavery]. Next day he speaks again at Springfield, pursuing the same course, with increased confidence and recklessness of assertion.[24]

Ethical rhetoric was important to Lincoln, who wrestled with whether or how to respond to Douglas’s demagogic methods. Lincoln sometimes resolved this dilemma with “turnabout is fair play” personal satire, at other times by satirizing his rival’s positions and policy. The rivals even debated the use of personal attacks.

In the c. August 21, 1858, fragment Lincoln also practiced his argument that Douglas’s refusal to recognize the immorality of slavery and indifference to its extension was designed to mold public opinion toward accepting slavery in free states. Lincoln drew upon the logic and language of this fragment during the rest of the debates and in the rhetoric he used in 1859 to advance the Republican cause and his political ambition.

Only three of the titles of Lincoln’s fragments assigned to his presidency relate to public discourse: Fragment of the House Divided Speech (December 7, 1860), written years after the speech was given (June 1858) in response to an autograph request; Fragment of Speech Intended for Kentuckians (February 12, 1861?; speech never given); and A Meditation on the Divine Will (September 2, 1862?). Lincoln studies discuss this latter fragment more than any other. White devotes the insightful, final chapter of Lincoln in Private to that fragment. Most of the sixty-two presidential notes concern appointments and promotions, sometimes referring to correspondence. Others relate to election data, military strategy, or campaign concerns.

Lincoln understood the importance of writing to advance his political and presidential work: he was an opportunistic but astute writer. He wrote in various places from workplace settings to private and secluded quarters, and he knew the power of putting down one word after another to discover and develop ideas, and refine language privately before public speaking and publishing to gain the desired effect.

D. Leigh Henson is Professor Emeritus at Missouri State University.

[1]John Channing Briggs, Lincoln’s Speeches Reconsidered (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005); Douglas L. Wilson, Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (NY: Alfred A Knopf, 2006); Fred Kaplan, Lincoln: The Biography of a Writer (NY: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2008).

[2]Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 2 vols. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 2008), 1:27.

[3]Wayne C. Temple, “Herndon on Lincoln: An Unknown Interview with a List of Books in the Lincoln & Herndon Law Office,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 98, No. 1/2 (Spring/Summer 2005), 35.

[4]For more information about the law offices of Logan, Lincoln, and Herndon in the Tinsley Building as well as the US circuit and district court of Illinois in that building, see R. Gerald McMurtry, ed., Lincoln Lore No. 1579 (September, 1969): 2–4.

[5]Temple, 35.

[6]William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Lincoln, ed. Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis (Galesburg, IL: Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College; Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1006), 113.

[7]Ibid., 243; Burlingame, Lincoln 1:756.

[8]Herndon and Weik, 251.

[9]Henry B. Rankin, Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln (NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1916), 378.

[10]Herndon and Weik, 287; Burlingame, 1:756.

[11]F.B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House (NY: Hurd and Houghton, 1866).

[12]David S. Reynolds, Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times (NY: Penguin Books, 2020), 612.

[13]Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time (NY: The Century Company, 1896), 298.

[14]Ibid., 300.

[15]https://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/washington/the-war-effort/war-effort-telegraph-office/.

[16]David Homer Bates, Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps During the Civil War (NY: The Century Co., 1907), opposite title page.

[17]Ronald C. White, Lincoln in Private: What His Most Personal Reflections Tell Us about Our Greatest President (NY: Random House, 2021), XV.

[18]Ibid., XVIII–XIX.

[19]Ibid.

[20]Roy P. Basler, et al., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55, 2:222.

[21]Ibid., 2:222–23.

[22]Lincoln, Speech at a Republican Banquet, Chicago, Illinois, Collected Works, 2:385.

[23]Basler, 2:454.

[24]Ibid., 2:549.