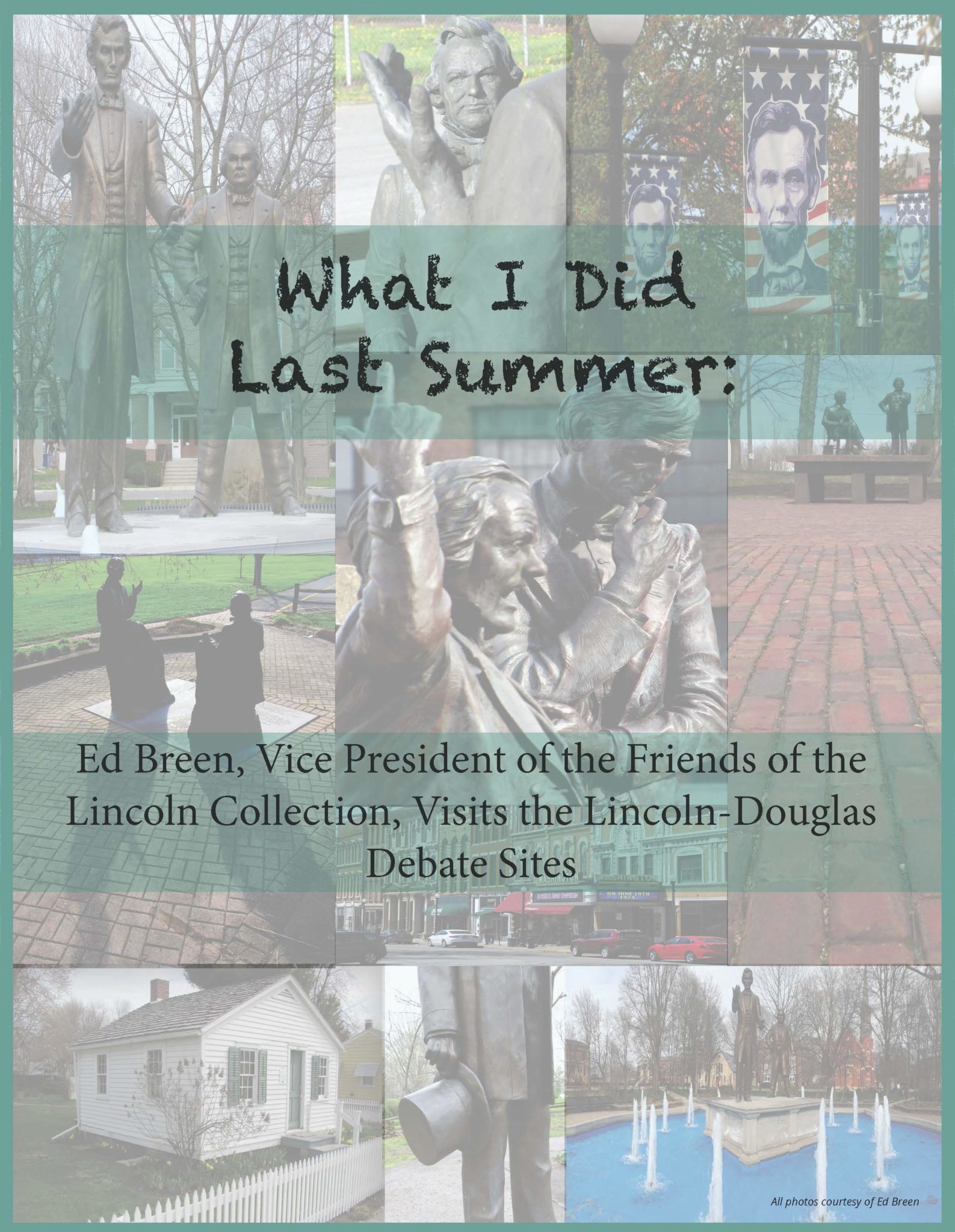

What I Did Last Summer: Ed Breen, Vice President of the Friends of the Lincoln Collection, Visits the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Sites

By Ed Breen

Charleston

Joe Judd sat behind the counter of his used book store at 303 Lincoln Avenue on the west side of Charleston, Illinois, and talked about what it meant to him and others in town that their town was among the seven communities across the Illinois landscape where the future of the United States of America was argued, discussed, and disputed 160 years ago this year.

“Debate” is the proper term. Judd’s town of Charleston was one of the seven sites, one in each Illinois Congressional District, (except for Chicago and Peoria, where the two had already spoken, one after the other) where the two great political heavyweights of the era—Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas — went toe-to-toe on lawns, platforms, hurriedly-erected stages and a couple of fairgrounds. These were the “Lincoln-Douglas Debates,” the bedrock arguments on how to correct what a 21st Century observer, Condoleezza Rice, called “America’s birth defect”: Slavery. What John C. Calhoun and others had once called “our peculiar institution.”

In Charleston, the confrontation between the two U.S. Senate candidates – Douglas the Democrat, Lincoln the fledgling Republican – was on September 18, 1858, midway through a schedule that had begun in Ottawa on August 21st and concluded in Alton, on the banks of the Mississippi River, on October 15.

“Oh, yes, it still means a lot. It’s a part of who we are,” Judd said, “but I don’t know that the young people really understand that. They maybe think it was just two old men.”

Judd, a man in middle age who graduated from Eastern Illinois University, just across the street from his bookstore, worked in Chicago and came back to Charleston (pop. 21,133) to raise his daughters. The town, like all of the towns on this particular circuit, is struggling with its economy. Jobs have departed from Charleston, the student population is about half of three decades ago, partly because the State of Illinois can’t afford to maintain the university as it once was.

“But you know,” Judd said with something resembling Chamber of Commerce pride, “Lincoln’s father and step-mother are both buried here, just a couple of miles from right here. Lincoln came through here after his election on his way to Washington and he stopped to see his step-mother out there in that little cabin. It’s still there. It would be like today if a President, with all his stuff packed in his car, stopped to see his mother living in a trailer at the edge of town.”

Thomas and Sarah Bush Lincoln are buried in Shiloh Cemetery just south of Charleston, the seat of Coles County and it was at the Coles County fairgrounds, a few miles to the north, that the debaters squared off on that Saturday in 1858, the day that local historian Charles Coleman described in his book on Coles County as “the biggest day in the history of Charleston.”

The site – as with all seven sites—is preserved and revered by the residents. There are Lincoln and Douglas statues, modest, smaller-than- life, and a museum maintained and staffed by volunteers.

Quincy

Statuary, the figures of Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Douglas, is found at all sites, except Quincy, where a larger-than-life bronze relief tablet marks the downtown spot and tells the story. Just across the street, of course, is the fine old Lincoln Hotel, now known as the Lincoln Douglas Apartments on Fourth Street.

Freeport, Ottawa, Alton and Quincy each possess central downtown squares where the debates were staged. Some – Ottawa and Alton, in particular — are lavish: Heroic bronze figures and carefully landscaped surroundings.

Galesburg

But perhaps most interesting is Galesburg, which makes the most of the convergence of Lincoln and his monumental biographer Carl Sandburg, who was born and reared in Galesburg and attended Knox College, the site of the fifth debate on October 7, 1858.

A platform was hurriedly constructed against the east wall of “Old Main,” the administrative building at the college, which appears pretty much unchanged today.

One problem: The raised platform, necessary if the estimated crowd of 20,000 was to see or hear the speakers, blocked the door leading from the building. Thus did the two politicians crawl through a window adjacent to the door and emerge on the stage.

The window is preserved. So is the red upholstered chair beneath the window which Mr. Lincoln allegedly rested in before climbing to the window.

“Oh, go ahead and sit in it if you’d like,” said Melody Diehl, Student Loans Coordinator for the college, whose office is adjacent to the historic waiting room and window. “We let everybody sit in it. Most of the commencement speakers stop here and sit in the chair. Madeleine Albright did, John Podesta did. Lots of famous people. Go ahead, you won’t break it.”

Halls of “Old Main” are lined with maps, photographs and artifacts, including a bronze Lincoln life mask and a painting depicting the enormous and partisan crowd which had assembled just beyond those doors.

And while there are no life-size statues of Lincoln and Douglas here, there is a larger-than-life rendering of Carl Sandburg at the heart of the downtown square. His childhood home is also an attraction south of downtown and within 100 yards of the once-sprawling and still active Galesburg railroad yards. White frame house, picket fence and a paving brick sidewalk. The house and visitor center are open Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.

Throughout the 420-mile expanse from Freeport, hugging up against adjacent Wisconsin, south to Jonesboro, wedged in at that time only a few miles from the slave-holding states of Kentucky and Missouri, are the remnants of the Illinois frontier. Two-lane blacktop roads link most of the towns. Family farms, both large and small, dot the landscape on both sides of the roads. These communities, by and large, are what remain. Tree-lined streets, architecture too ornate and expensive to be built or maintained today. Courthouse squares and in each of these special places bound together by history, special parks set aside to mark what happened all those years ago.

Jonesboro

Jonesboro is the smallest of the towns, population 1,749. Said Lincoln of Douglas on his arrival in Jonesboro: “Did the Judge talk of trotting me down to Egypt to scare me to death? . . . ” (Southwestern Illinois has long carried the moniker of “Little Egypt” because the central town of the region is named Cairo).

The Jonesboro appearance, third in the sequence, was the most distant from the Midwestern Illinois frontier— geographically and culturally— and also the most sparsely attended; the crowd was estimated at 1,500. It is also the most rural of the settings. The bronze statues are surrounded by live oak timber, including a massive oak believed to have been there on that September day 160 years ago.

It is surrounded by the Trail of Tears State Forest, a commemoration of the forced removal through the area of the Cherokee Native Americans.

And that is the most abiding of impressions from the seven-town tour: That the evidence of events past is inescapable across the arc of Illinois from Wisconsin south to the Ohio River.

The Lincoln and Douglas debates, certainly the focus of 1858, were but a slice of the continuum of history across this western frontier of the Old Northwest Territory, the huge swath of America created by Ordinance in 1787, territories (and later, states) in which slavery was prohibited by statute.

Ottawa

In Ottawa, Ryan Prusynski, a teenager, served up fries at McDonalds and talked about his town.

Yes, that date, August 21, still looms large. “We went there on school trips when I was in third grade and again in sixth grade,” he said, motioning in the direction of Washington Park in downtown Ottawa where the debate occurred. Adjacent to the park is a half-block-long urban mural painted in 2007 depicting what went on across the street in the park all those years ago.

“The kids in Ottawa Township High School now go to the park and read aloud the texts from the debates that day,” the young Ottawan said. “But, you know, the thing we talk about more is the radium poisoning, the places that are still contaminated.”

That all began in 1922 when the Radium Dial Company set up shop in a former high school building in Ottawa and hired hundreds of young women to paint wristwatch dials, using radioactive paint that caused the watch dials to glow in the dark. Thus were wearers able for the first time to roll over in bed in the middle of the night, glance at their wristwatches, satisfy their curiosity and go back to sleep.

The result, as we know in a better informed era, was massive radioactive contamination of both people and places in Ottawa. Residents, particularly the young women applying the paint, ingested huge doses of Radium radiation that led to illness and death from anemia, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has been a constant presence in Ottawa since 1986 and some areas of the community are still uninhabitable.

Thus did the glow of wristwatches overshadow that August day in Ottawa.

Alton

Down the road, 220 miles southwest of Ottawa, is the Mississippi River town of Alton, a town of 27,000 that is really a far northern suburban St. Louis, but it seems not to have benefitted from location.

Its shrine at the October 15 debate site is within sight of the river, a presence which drives so much of all Mississippi River towns, past and present.

The downtown site is expansive and elegant, with statuary created by artist Jerry McKenna. He was selected by a committee of the Rotary club and produced a Lincoln and a Douglas who are both life-sized and life-like with animation and expression that seem to befit what we know of that day.

Francis Grierson, a local historian, was there:

“This final debate resembled a duel between two men-of-war, the pick of a great fleet, all but these two sunk or abandoned in other waters, facing each other in the open, the Little Giant hurling at his opponent, from his flagship of slavery, the deadliest missiles, Lincoln calmly waiting to sink his antagonist by one simple broadside.”

“Alton had seen nothing so exciting since the assassination of Elijah Lovejoy, the fearless Abolitionist, many years before (in 1837)”

Alton seems to have wrapped itself around the era unlike any other place.

Just down the road, still hugging the bank of the great river is the home of Lyman Trumbull, United States Senator from Illinois, who, as Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, helped to draft the language of the Thirteenth Amendment, the final and uncompromising language that brought an end to the debate and the bloodletting, the prohibition of slavery in the United States of America.

A half century earlier, the 1,000 inhabitants of the river town had gathered on its bank to watch the passing parade of the Corps of Discovery – the Lewis and Clark Expedition – as it ascended the river toward the unknown of the far west.

And the great debate came and went and the war came and went. And not at all incidentally, Alton is the birth and nurturing place of one of the most iconic of American musicians. Jazz trumpeter player Miles Davis was born in 1926 in Alton into an affluent African-American family. His mother was a teacher and violinist; his father, a dentist.

And so it is, up and down the breadth and depth of these Illinois communities. Historic people and historic events came and went over 200 years, bookends to a few weeks and a few events which gave shape and form to who and what we are today.

Freeport

This is no better demonstrated than 310 miles to the north in Freeport, another Midwestern town struggling to preserve its past and develop its future.

At the corner of State and Douglas streets is Debate Square. It is a couple of blocks east of the most dominant structure on the Freeport skyline: The 83-foot limestone obelisk, the Soldiers’ Monument, erected in 1871 as a tribute to the Stephenson County men who served and died in the Civil War.

Slightly more than an acre, Debate Square was the site of the second of the seven debates and seems to be the place where Douglas framed his “Freeport Doctrine,” a delicate balance between popular sovereignty and judicial determination on the future of slavery.

The Freeport statues give life to the scene, display tablets describe what happened there, including newspaper accounts of the day. Probably only coincidental, but in most of the sculptural interpretations, including Freeport, the chosen moment depicts an animated Douglas and a contemplative Lincoln

But it is next door, at the Union Dairy ice cream shop at 126 E. Douglas Street, that all of this – the speeches, the memorials, the statues, the memoirs and the transcripts – seems encapsulated in the life and times of Ron Allen, a middle-aged African-American.

Allen was born and reared in Chicago, in “the projects,” he says with no rancor and some pride. The Ida B. Wells House between 37th and 39th streets on the South Side of the city. An early attempt at public housing built just prior to World War II.

His mother, he said, came to the city from the South, from Mississippi, part of the post-war African-American migration from rural to urban America. There is no mention of his father.

He was educated in Chicago and came to Freeport at his mother’s insistence.

“God bless my Mama,” he said, adjusting his cap and walking from his apartment in the Union Dairy building the 100 feet to the park. “I’m here because she didn’t want me killed in Chicago.”

He and his wife Amy, who is white, live in the modest apartment beside the ice cream shop.

“Been here a long time,” he said. “Oh yes, we watch the people come to the park. Usually they come here first and get an ice cream cone, then they go over to the park and look at all the statues, then they read the stuff on the signs and then go on.”

Does he identify with what happened here? Evaluate its importance in the national life and, more importantly in his life? No, not really.

“What happened here?” he said. “Why back in those days in Freeport there was so much goin’ on and so many women over there,” he said pointing to the southeast, “that mostly they didn’t know there was a debate here at all.”

He laughed, re positioned his cap and returned to be bench and sat down with his wife in front of their apartment to simply watch and wait and get into these kinds of conversations.

The legacy of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 160 years ago?

It persists in these Illinois towns.

It is partly preserved in the bronze statues.

And it partly – and more importantly – resides in the lives of those living at 130 E. Douglas Street in Freeport, and at 303 Lincoln Avenue in Charleston, Illinois.