The Woman Who Found Lincoln at Gettysburg: Josephine Cobb of the National Archives

The Woman Who Found Lincoln at Gettysburg: Josephine Cobb of the National Archives

By Mark B. Pohlad

For nearly ninety years there were no known photographs of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg.

That changed dramatically in 1952 when the intrepid Washington, D.C., archivist Josephine Cobb (1906-86) went searching—and found him. She enlarged a mislabeled glass plate negative until she identified Lincoln’s face in the crowd. The War Department had purchased the image as part of a collection from Mathew Brady in 1875; the army moved the group to the National Archives in 1941 where it came under Cobb’s purview. Its historical significance had gone unrecognized for ninety years, and it may have remained so today. Her discovery is the closest thing we have to an actual visual record of the Gettysburg Address––one of Lincoln’s, this country’s, and democracy’s finest moments.

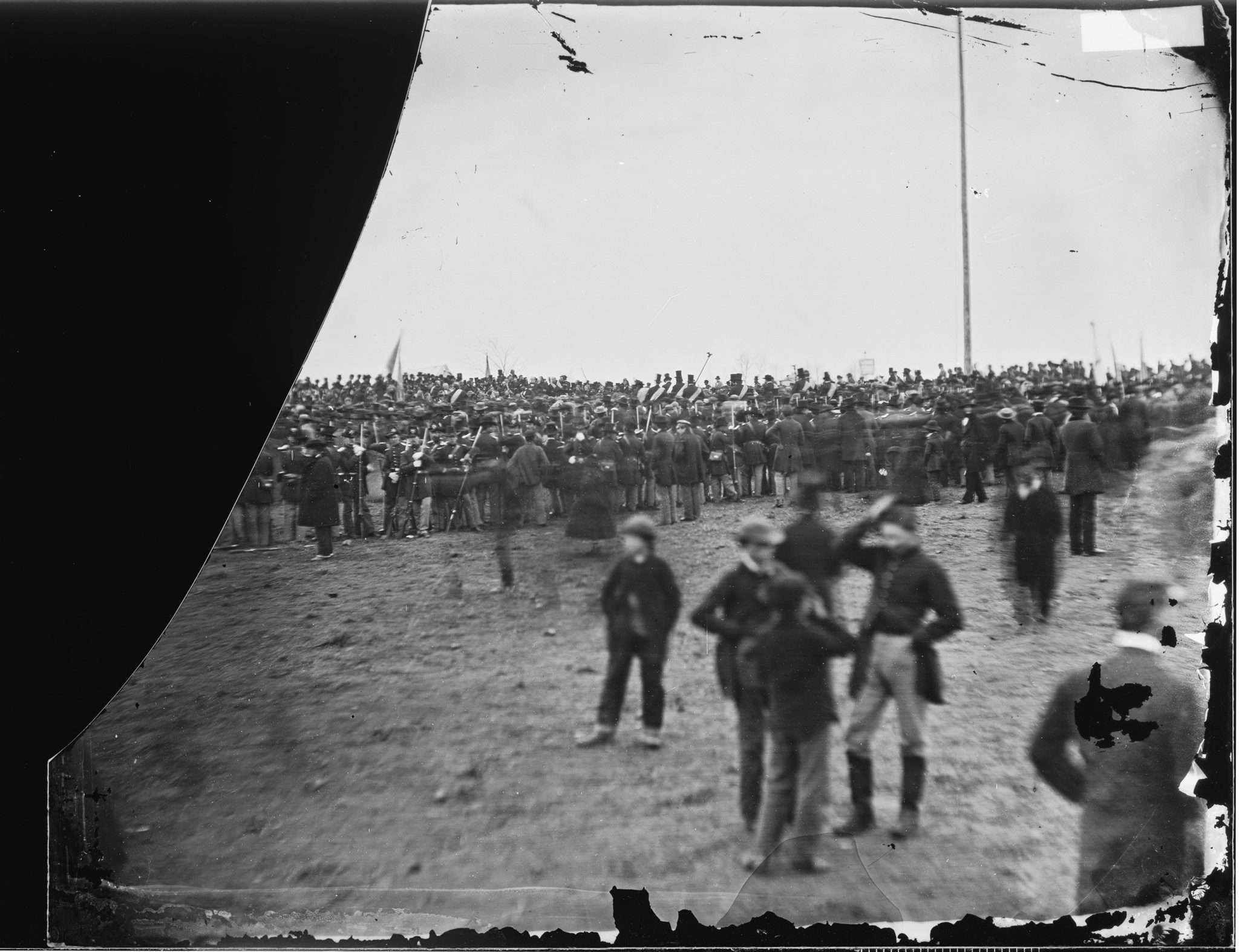

In the image, a group of boys are milling about casually in the foreground. A crowd can be seen very deep in the background; it is so dense that no individual can be distinguished in it. But Cobb intuited that it might have valuable information to offer. The tallest flag, she reasoned, might mark the location of a speaker’s platform, a promising place to search for dignitaries. She enlarged the image repeatedly—some twenty times––until she could make out the bare-headed, downcast, bearded face of Abraham Lincoln. Cobb had not only found the war-weary president in the photo, she had also found the first known photograph of the dedication at the Soldiers’ Cemetery at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. Within hours of when the exposure was made, Lincoln would speak the most famous piece of oratory in American history—273 words that redefined the war and the meaning of freedom in this country.

Cobb estimated that the image was probably exposed around noon when the president and his cortege arrived on the speaker’s platform, still three hours before his own “few appropriate remarks.” Given the position of his head and shoulders, he appears to be taking his seat. Cobb identified Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, directly to Lincoln’s right, along with Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, the official host of the event, seen in great clarity at the far right. Other observers have recognized Major General Robert C. Schenck on Lincoln’s left and Edward Everett in the upper right, hands on hips and perhaps looking around (because his face is thoroughly blurred). Lincoln’s secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, are here too. So well known is the enlargement showing Lincoln’s face that many viewers are genuinely shocked to see the original photograph from which it came. Even when the two images are seen side-by-side, it is not immediately obvious how they relate to each other. Moreover, the glass plate itself is broken; about a quarter of the upper left side is gone, giving it a roughly trapezoidal shape. It is possible the cameraman made a random shot merely to get rid of a defective plate.

Many people erroneously believe that the detail shows Lincoln seating himself after he has already delivered his famous speech. They claim that the photographer was caught short because he thought he would have enough time to capture the president speaking. After all, the previous speaker, Edward Everett—a former Secretary of State, Harvard president, governor, and congressman––had spoken for two hours. This narrative has currency because it corroborates the startling brevity of the Gettysburg Address, just a couple minutes or so. But since the detail of Lincoln comes from a very distant crowd scene, where the president would be virtually invisible anyway, it cannot be the case that the photographer intended to take this picture during his speech. Apart from what the image shows, most perplexing of all has been determining who took the picture in the first place. Researchers disagree; many believe it to have been Alexander Gardner, others David Bachrach, and still others an anonymous Brady “operator.”

It is difficult to imagine a time when we did not possess the image of Lincoln at Gettysburg, for Cobb made her discovery a full sixty-seven years ago, in late 1952. At that time, not even a century had passed since Lincoln’s assassination. Incredibly, a couple of Civil War veterans were still alive. In fact, an article about the hundred-and-sixth birthday of a Union drummer boy appeared on the same front page of the newspaper where Cobb’s discovery was first announced.[1] The year 1952 was a kind of annus mirabilis for Lincoln and photography. In that year the last picture of Lincoln “from the flesh”—a photograph of his body lying in state in an open coffin—was discovered by teenaged Ron Rietveld. As in Cobb’s case, he had also found Lincoln hiding in plain sight, in a photograph he came across while perusing the cabinets and drawers of the Illinois State Historical Society. Finally, 1952 was also the year in which the photohistorian Helmut Gernsheim discovered the oldest known photograph of all: Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras, of 1827.

On Lincoln’s birthday in 1953, a small, front-page article in the Gettysburg Times announced Cobb’s discovery.[2] Soon the story would be reproduced in newspapers across the country. A week later, Life magazine ran a small story featuring Cobb’s detail of Lincoln on the speaker’s platform.[3] Its glib first sentence ran, “Long lost photographs of Lincoln have a way of turning up just in time for Lincoln’s birthday.” It then recounts how “going over a collection of 5,000 miscellaneous Matthew [sic] Brady photographs, Josephine Cobb of the National Archives in Washington found one labeled ‘crowd of citizens, soldiers, etc.’ which she has tentatively identified as showing the Gettysburg ceremony.” The author continues, “The face of the bearded man who may be Lincoln is slightly blurred making positive identification almost impossible.” In the announcements of Cobb’s discovery, her claims are invariably described as “tentative,” likely at her own insistence. But there is enough visual information in the detail to make it certain––Lincoln’s location in the crowd, the many glances directed at him, the long, thin face, the familiar hair pattern, and even his characteristically crooked tie. In the years since Cobb found Lincoln, no one has challenged her claim.

Cobb’s find became even more well known after it appeared in Stefan Lorant’s lavish picture book, Lincoln: A Picture Story of His Life in 1957.[4] Throughout her career, she had frequently helped Lorant with his projects. In Cobb-like fashion, Lorant once enlarged a photograph of Lincoln’s New York City funeral procession to find young Theodore Roosevelt peering down from a window. A review of Lorant’s Lincoln: A Picture Story of His Life claimed that Cobb, in order to find Lincoln, had enlarged the negative 100 times, and Lorant 250 times in order to reproduce it in his book.[5] In the 1960s and beyond, the image became so well known that viewers forgot that its discovery was actually someone’s achievement.

Two years before unearthing the Gettysburg plate, Cobb brought to light another Civil War-era photograph containing a Lincoln look-alike.[6] In 1950 she became intrigued by an 1863 photograph labeled “Hanover Junction, Va.” But something seemed a bit off. That town, she knew, is only twenty miles north of Richmond, well within Confederate lines during the war. And noticing that the soldiers were wearing Union uniforms, she reasoned that the image must instead have been taken in Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania. For many viewers, the 1863 date raised the possibility that the tall, top-hatted figure seen in it was Lincoln on his way to Gettysburg. It created a great deal of excitement in the Lincoln community (recall that there were no known images of Lincoln at Gettysburg before her enlargement-based discovery.) Ultimately, Cobb did not believe that it was the president in the photograph, but not before she had conducted her own extensive research. In any case, carefully examining mislabeled photographs––then exercising extreme caution in making claims––would prepare her for her own positive identification two years later of Lincoln at the Soldiers’ Cemetery in Gettysburg. Had Cobb lived into our own time, she would have been intrigued with more recent examinations of Gettysburg stereoscopic photos purporting to show a top-hatted Lincoln on horseback. Researchers of those images employ the same principles of enlargement she had used so effectively in 1952.

Cobb’s background prepared her well for her image-based research. She grew up in South Portland, Maine, in the eighteenth-century home of her ancestors. Her father was a journalist who often wrote about the history of the state; a grandfather had served in the Union army. After high school, Cobb earned a bachelor’s degree from Simmons College in 1931. She worked in the rare books room of the Boston Public Library and at the venerable Massachusetts Historical Society. Her M.A. thesis from Boston University four years later recommended the establishment of a national research collection before anything like it existed. At American University in Washington, D.C., she studied the relatively new field of archival sciences. When the National Archives was established in 1936 and hiring only men, Cobb boldly ventured there and secured a position as its first woman employee, “Assistant Archivist in the Photographic Archives and Research Division.” Among her duties was cataloguing Frederick Hill Meserve’s collection with the assistance of his daughter, Dorothy (1901-1979). It marked the beginning of a long association with members of the renowned Kunhardt family.[7] Over time, the photographic department at National Archives grew and improved, including—crucially for Cobb’s Gettysburg discovery––its ability to enlarge images. She closely monitored these innovations while becoming intimate with the holdings. A sensitivity to photographic media seemed to be in her DNA; her brother Allen was employed at the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York.

Cobb occupied positions at the National Archives for thirty-six years as a cataloger, specialist in Civil War subjects, and later as Chief, or Archivist-in-Charge, of the Still Picture Branch. Some of the earliest photographs accessioned by that department were of the Civil War, and it was this era that became her specialty. Her exhaustive research on Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, as well as on photographs of Abraham Lincoln and Civil War photography more generally, made her well known, even legendary. Over the course of decades, Cobb was a devoted contributor to professional and academic associations. A medal recipient for her work on the Lincoln Sesquicentennial in 1959, she was also long a member of the distinguished Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia and served as its president in 1970 and 1971.

Cobb looked like the consummate professional—tall, thin, immaculately dressed, and tidily coiffed. Entirely engrossed in her work, it became part of her endearingly quirky personality. As a young scholar, Harold Holzer had a memorable experience with her “eccentric side.” “Once,” he recalled, “Miss Cobb pressed her forefinger to her lips as if to hush our conversation, then slowly opened a drawer in her old wooden desk, whispering: ‘I am going to show you a rare daguerreotype. If you can tell me who it portrays, I will consider that you have graduated into a real student of Civil War photography.’ And then, almost conspiratorially, she handed me a small plate, covered completely in wax paper and secured by an orange rubber band. ‘But I can’t see it, I protested. It’s wrapped in wax paper. May I remove it?’ ‘Of course not,’ she snapped, snatching it back and replacing it in her drawer. ‘That would make it too easy.’ So much for graduating.”[8] According to the conventions of the day, she was always officially referred to as “Miss Josephine Cobb.” Holzer recalled that she affectionately signed her letters, “your friend, J. C.” Acquaintances called her simply, “Jo.”

Not merely a librarian, Cobb was also an accomplished scholar in her own right. Her publications and conference talks were meticulous and exhaustive. Her groundbreaking article “Mathew B. Brady’s Photographic Gallery in Washington,” on which she must have been at work when she found Lincoln at Gettysburg, was the first detailed examination of the social and commercial realities that shaped Brady’s career.[9] Not sequestered in the stacks and archives, she was also doing field work with people from the Civil War era. Cobb once interviewed octogenarian Lydia Mantle Fox who had known Brady personally and who provided many details about Civil War-era Washington photography.[10] Encounters like this were still possible in the 1950s, but it took an enterprising soul to find and conduct them. Her interest in the field was consuming, an editorial note in her article alerting the reader that “Many years of research, much of it on her own time, have made her an outstanding authority on Brady and his work.”[11] Indeed, Cobb told a reporter in 1951 that, even though she would prefer to devote her life to studying Brady, “As it is, I have to chisel to get extra time to work on him, for as head of a section here I am constantly called upon to fill out forms and beat people over the head for statistics.”[12] Among the many original insights she makes in this essay is one concerning the chair in which Lincoln sits in Gardner’s portraits. Her discussion of where such chairs were made, who owned them, and where they could be found, is contained in a single remarkable footnote.[13] We also learn that, among the presidential candidates in the 1860 race, Brady favored Stephen A. Douglas over the rail-splitter candidate.[14]

Likewise, Cobb’s superb biographical article “Alexander Gardner” was the most accurate and comprehensive study of the cameraman until the first book-length treatment three decades later.[15] It is still worth consulting for the photographs she reproduces, which are startlingly contemporary looking, and for the intriguing details of Gardner’s life and career she recounts. These include how Gardner rescued his fifteen-year-old son from the boarding school in Confederate-controlled Emmitsburg, Maryland, just before the nearby battle at Gettysburg. Or how, long after the war, Gardner and his wife dressed members of the Indian delegations to Washington in old, “smelly” costumes with beads and feathers because their attire had become too Americanized.[16]

Cobb was deeply engaged in her topic, but not a fanatic merely in love with the medium. Proof of that is seen in the first line of another of her articles: “Photography’s part in the Civil War was not significant to either military or naval operations and it had no part at all in the organization of the forces of either North or South.”[17] She was sober and realistic, which made her a good judge of what represented a genuine contribution to the field. Accordingly, that same piece concludes with her “List of Photographers and Their Assistants with Military Units,” some three hundred names, “most of whom have been forgotten despite their contribution to the views of the Civil War.”[18] It is a breathtaking piece of historical research and still indispensable today. Nor was Cobb’s research limited to photography. Just as she found Lincoln’s face at Gettysburg, she did the same for Gardner’s when she uncovered a rare painted portrait of the “camera-shy” cameraman.[19] She was also particularly knowledgeable about Masonic history and its imagery, her Maine relatives being long-time members of the Order. Cobb even wrote the foundational essay on collecting patriotic envelopes, a marvelous source of political graphics in the war era. In this article, she characteristically enlarges some examples, speaks at length about those that show Lincoln, and explains papers and pigment composition in terms that would impress a conservator.[20]

Given this wide range of expertise in nineteenth-century visual culture, after 1962 Cobb’s title at the National Archives had changed to “Specialist in Iconography.” It was the first such use of that term in relation to an archivist, one whose interests spanned a vast range of media and their intersection. Along these lines, at a 1962 Library of Congress symposium on “American Printmaking Before 1876: Fact, Fiction, and Fantasy,” she spoke about how prints were often based on a range of photographic media and could therefore be trusted as accurate representations. Indeed, Cobb read widely in her field and held strong, informed opinions, as seen in her book reviews for American Archivist in the 1960s. About a new edition of Beaumont Newhall’s even-then classic survey of the medium, History of Photography, she claimed that he had omitted some fifty important photographers. Furthermore, as she said, “Mr. Newhall writes largely of the contributions made by those of English-speaking countries, giving less attention to the contributions by those who work and write in other lands and tongues.”[21] Here Cobb leveled the kind of criticism that inclusive-minded humanities scholars only began making thirty years later.

Beyond her own superb scholarship, her best work consisted of her day-to-day assistance to researchers for their own projects. She was instrumental in the books of many of the twentieth century’s most important historians. Searching her name on the Internet reveals countless publications by authors on Civil War-era photography, Abraham Lincoln, and the American West, in which they acknowledge her assistance. Those who visited her in room 14-N of the Archives Building in Washington, D.C. (after 1959) were genuinely helped along in their work. Later in her career, she even conducted graduate seminars for future museum directors and librarians. To be sure, Cobb’s expertise and good judgment suffuses the field even now.

After retiring from the National Archives in 1972, she returned to her childhood Portland, Maine, and built a beautiful home in Cape Elizabeth overlooking the sea. Cobb turned her attention to local history, working with state organizations such as the Maine Old Cemetery Association and the Maine Historical Society. She helped convert the latter from “an old boys’ club” into something more public and inviting. “She was of that generation that made things pop,” one local historian said.[22] In her large library of books were volumes signed to her by researchers and notables such as Carl Sandburg. Replaying the type of work she had done for the National Archives, Cobb now carefully curated the photographs she herself owned, composing a six-volume catalogue of her collection of daguerreotypes.[23] She carefully labeled the 245 images and had copy prints made of each. This intimate archive was her final gift to the field. Cobb’s last few months were especially difficult, as she suffered from Alzheimer’s.[24] A nightmare for anyone, of course, the disease is perhaps especially devastating for archivists who have dwelt in a world of order and detail.

Anyone else might have written a book or article about the discovery of Lincoln at Gettysburg, for such an achievement could launch or crown a Lincoln scholar’s career. But it was characteristic both of Cobb’s humility, and perhaps her ethics as an archivist, that this discovery was unselfishly given to the field as simply more information about an object under her care. Considering her importance to Lincoln scholarship, to Civil War studies, and to the history of American archives, it is unimaginable that to date there is not a single piece of scholarly writing on her. Nor are there any obituaries or appreciations to be found online. Sadly, she did not receive any acknowledgement in the recent televised documentaries celebrating the sesquicentennial of the Gettysburg Address, even though the image of Lincoln she found was often analyzed in detail.

Surely, Josephine Cobb joins the ranks of major Civil War-era photohistorians such as Frederick H. Meserve, Stefan Lorant, Lloyd Ostendorf, Robert Taft, and the Kunhardts. She should also be regarded as a pioneering historian of American visual culture. In all, her discovery of Lincoln at Gettysburg was neither inevitable nor a matter of luck. It was the result of her years-long engagement with the collection of the National Archives and a function of her expertise and hard work. She well deserves to be part of the narrative of the beloved image of Lincoln at Gettysburg.

Mark B. Pohlad is an Associate Professor of Art History at DePaul University, Chicago.

Endnotes

[1] “Discover Gettysburg-Lincoln Picture in National Archives at Capital After 90 Years.” The Gettysburg Times, February 12, 1953, p. 1. The drummer boy was Albert Woolson (1850-1956) “one of the last two living veterans of the Union Army.”

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Lincoln at Gettysburg?” Life, February 20, 1952.

[4] Stefan Lorant, Lincoln: A Picture Story of His Life (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1967), 277, 299.

[5] Joseph Gies, “Picture in a Million,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 7, 1957, 140-41.

[6] The Gettysburg Times, “Claim Photo in Times Was Abraham Lincoln,” October 4, 1952, 2.

[7] Cobb worked with Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and her son, Philip B. Kunhardt, Jr., on the Time-Life Books study Mathew Brady and His World (1977).

[8] Frank J. Williams and William D. Pederson, eds., Lincoln Lessons: Reflections on America’s Greatest Leader (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 46.

[9] Josephine Cobb, “Mathew B. Brady’s Photographic Gallery in Washington,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 1953-1956 (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society, 1957), 28-69.

[10] Ibid., 68n78.

[11] Ibid., 28.

[12] Jane Eads, “Capital Letter,” Greenville (PA) Record-Argus, February 21, 1951, 7.

[13] “Mathew B. Brady’s Photographic Gallery in Washington,” 45n34.

[14] Ibid., 46.

[15] Josephine Cobb, “Alexander Gardner, Image 7, no. 6 (June 1958): 124-136. See Mark D. Katz, Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner (New York: Viking Studio Books, 1990).

[16] Ibid., 133, 134.

[17] Josephine Cobb, “Photographers of the Civil War,” Military Affairs 26, no. 3 (Autumn 1962): 127-135.

[18] Ibid., 129-35.

[19] Charles Hamilton and Lloyd Ostendorf, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 122. Other photographic portraits of Gardner have since been discovered.

[20] Josephine Cobb, “Decorated Envelopes in the Civil War,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 1963-1965, ed. Francis Coleman Rosenberger (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society, 1966), 230-239.

[21] Josephine Cobb, “Reviews of Books,” The American Archivist 28, no. 3 (July 1965): 448-457.

[22] Leslie Bridgers, “Picture of Success: Lincoln Discovery Made Local Woman’s Success,” Keep Me Current [Falmouth, Maine], February 7, 2007.

[23] They are now a part of the Harvard Library’s Harrison D. Horblit Collection of Early Photography.

[24] I am especially grateful to Alan H. Hawkins, Cobb’s close friend and Maine neighbor, for sharing details of her personal life.