The Mystery of Lincoln’s Second Flatboat Trip to New Orleans

The Mystery of Lincoln’s Second Flatboat Trip to New Orleans

Glenn W. LaFantasie

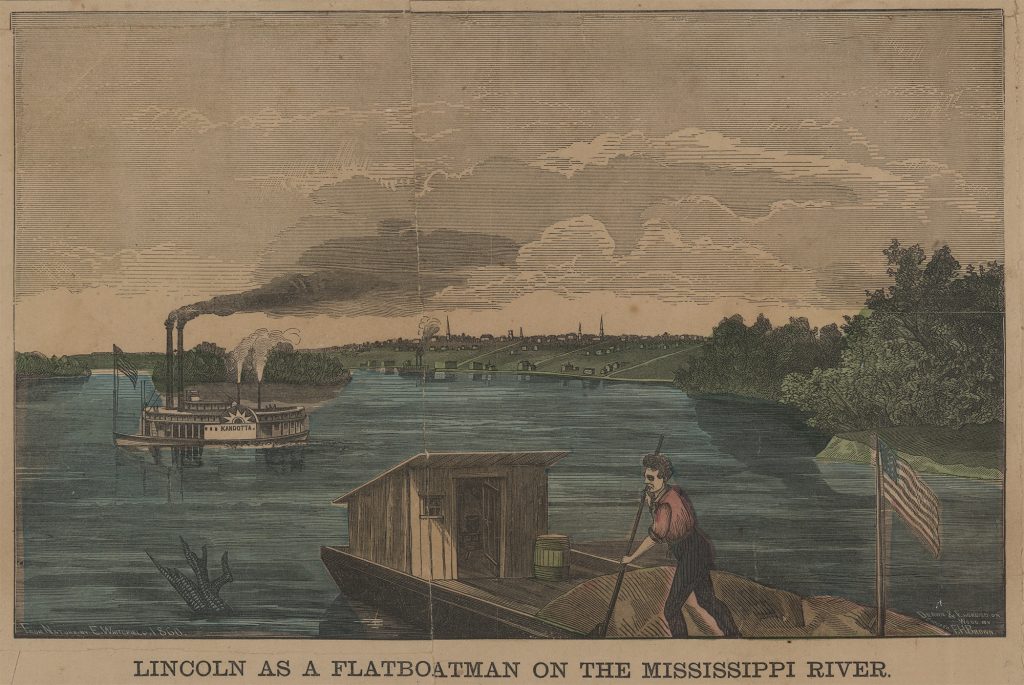

In his youth, Abraham Lincoln took two trips down the Mississippi River on flatboats laden with goods to be sold in New Orleans. The first trip occurred in the spring of 1828, when Lincoln lived in Indiana and agreed to accompany Allen Gentry, a merchant’s son, down the Ohio River and the Mississippi to the Crescent City, the fat southern market city where westerners knew they could get top dollar for anything from pork to corn whiskey, tobacco to sorghum. The voyage must have been an eye-opener for Lincoln because he had never ventured far from his family’s home in Spencer County. Both diligence and vigilance were required, for, as Mark Twain later explained, the Mississippi “had a new story to tell every day.”

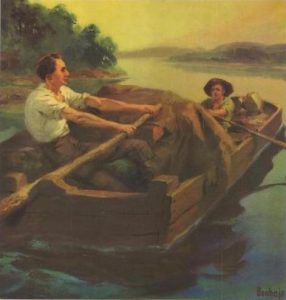

During the long trip, boisterous storms whipped at the bobbing flatboat, sometimes threatening to scuttle the vessel, crew, and goods. The rain soaked them through to the skin; the wind chilled them to the bone. At night they tied up close to the river’s bank, bedding down on the hard wood of their “running board,” as flatboats were sometimes called, and shivering themselves to sleep. A flatboat, Lincoln once remarked, floated “faster than an egg-shell,” but in places the currents varied, and sometimes the vessel languished, only helped downstream by Lincoln using a pole or oar. When the going was slow, and people stood on the banks watching the flatboat slip by, it was possible to strike up a lazy conversation. Meanwhile, Gentry steered the flatboat as best he could, avoiding the sometimes-busy traffic on the rivers that included other flatboats, keelboats, and a high number of churning steamboats.

Along the way, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked one night at a landing by a group of Black marauders wielding hickory clubs. The ambushers, Lincoln recollected some three decades later, intended “to kill and rob them.” Despite the surprise and the depths of darkness, he and Gentry fought back with vigor. Lincoln grabbed a club and knocked several of the attackers into the river. With quick wits, Gentry shouted out, “Lincoln get the guns and Shoot,” a ruse to make the attackers think the two boatmen were armed. Almost at once, the Black men fled into the night, pursued by their wounded victims. Eventually, Lincoln and Gentry gave up the chase and returned to the flatboat, where they discovered their wounds from the fight were bleeding. Fearful that the raiders would return, the boatmen cut their vessel loose and, finding “the middle current,” drifted downriver until daylight gave them comfort and made them feel more secure. Lincoln carried a scar from one of his wounds for the rest of his life. The rest of the trip was uneventful, although there is no record of Lincoln’s impression of New Orleans, which was among the country’s biggest cities and certainly the largest one he had ever seen so far in his young life.

The second flatboat journey happened a few years later, in April 1831, when Lincoln, who had recently arrived in Illinois and gone off on his own, compared himself to “a sort of floting Drift wood.” But this second voyage contains a mystery that historians have failed to solve conclusively. Unlike Lincoln’s earlier trip to New Orleans, this venture did not involve any high adventure with marauders, but it is mysterious because the extant records only vaguely reveal precisely who comprised the crew of the flatboat after a stop at St. Louis on the journey south, and who accompanied Lincoln on the crew’s return to Illinois.

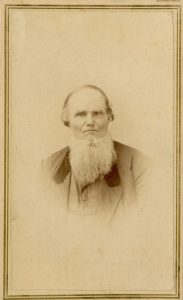

At the center of the mystery are Lincoln and his cousin John Hanks, the person who had persuaded Thomas Lincoln to relocate his family from Indiana to Illinois. Hanks, who had lived for a while with the Lincolns in Indiana, appeared every bit the weathered pioneer with his round face, high forehead, scraggly beard, and impish look in his eyes. To earn money during the winter of 1830–1831—when a tremendous blizzard called the “Deep Snow” covered the prairie in two to three feet of snow, after which high winds and arctic cold created drifts up to twenty feet high—Lincoln and Hanks found work doing various chores for the local farmers stranded in their cabins. They also worked splitting rails—hundreds, perhaps even thousands of them. As temperatures rose again with the advent of spring, the thaw produced a great flood in which rivers and streams overflowed their banks and travel could be accomplished only by floating vessels of low draft, like canoes and makeshift rafts.

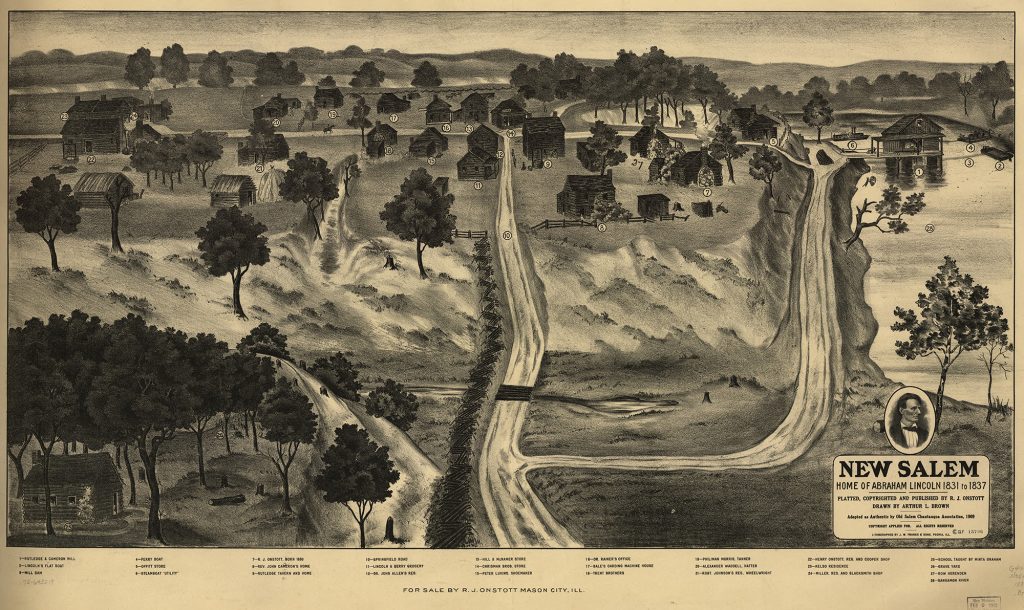

Nevertheless, John Hanks, a boatman of high reputation, arranged with Denton Offutt, an amiable but not entirely trustworthy enterpriser, to hire Lincoln and his stepbrother John D. Johnston to man a flatboat to New Orleans. There, Offutt wanted to sell various goods for cash to finance a store in New Salem, a pioneer village on the Sangamon River that many believed was destined to become a significant entrepôt. None of them knew that Offutt, who stood about six feet tall and had a dark complexion, black hair, and a missing front tooth, was a skilled huckster and confidence man. He was described a few years later as “very talkative” and trying to “pass for a gentleman.” The three men were supposed to meet their new employer in Springfield, Illinois, but for hours they slogged through the town’s muddy streets without finding him. Finally, they discovered him sound asleep in a dingy corner of the Buckhorn Tavern, where he was three sheets to the wind. Soon they learned that he had failed to acquire a flatboat, a sure sign of the man’s almost total lack of responsibility. After sobering up, Offutt tried to redeem himself by hiring the three young men to build the flatboat for their journey south.

Lincoln, Hanks, and Johnston agreed to do so, and they constructed it in Sangamotown, about eight miles northwest of Springfield on the Sangamon River. Many decades later, John Roll, a local worker hired to make the pins for the boat, vividly remembered his first sight of Lincoln. “He was a tall, gaunt young man,” said Roll, “dressed in a suit of blue homespun jeans, consisting of a roundabout jacket waistcoat, and breeches which came to within four inches of his feet. The latter were encased in rawhide boots, in the tops of which, most of the time, his pantaloons were stuffed.” Lincoln’s soft felt hat had once been black, but now, after much wear, was, in the young man’s own words, “sunburned until it was a combine of colors.” Actually, Lincoln looked much like any other man of the time, except that his legs were longer, his frame was skinnier, and his face—while not unpleasant to the eye—left some people fretful about his homeliness. Other people, however, were of two minds about his appearance. Said one woman who had met Lincoln during her childhood: “I considered Lincoln the ugliest person I ever saw, but in time his face grew to be good-looking.”

As they built the flatboat, Lincoln talked incessantly. In between the thuds of axes and hammers, he frequently commented on the books he had read—“Shakespear & other histories and Tale Books of all Discription.” During his stay in Sangamotown, Lincoln read a book about Francis Marion and his partisans during the Revolutionary War and “an old blue-backed life of Washington,” and these may have been among the books he discussed with the construction team as they worked on the flatboat. Occasionally he recited his favorite poetry or prose passages gleaned from his voracious reading. Most of the time, however, he spoke about politics. One Sangamotown resident described young Lincoln as “a John Q Adams man & went his Length on that Side of politics.” In the rising spring of 1831, Lincoln made plain his devotion to Adams’s National Republican Party, a forerunner to the Whig Party, which would fully emerge three years later under the leadership of Henry Clay of Kentucky. Although the National Republicans fervently opposed practically everything that President Andrew Jackson said and did, Lincoln’s conversations on politics, as he smoothed rough planks with an adze and pounded pins into augured holes, defended the Democratic president, especially when his fellow workers disparaged the chief executive with lies or statements expressing outright malice. Hanks remembered that Lincoln “could not hear Jackson wrongfully abused.”

Lincoln’s political stance revealed an unusual sophistication for a young man of twenty-two, not only in his attitude toward the politics of his time, but about how he could readily keep his personal feelings and his political beliefs separate, coexisting in different spheres. For the rest of his life, his ability to segregate personal convictions from political principles became a stunning hallmark of his civic life. Remarkably he never treated his political enemies as mortal ones, although in private he sometimes spoke of his opponents more damningly. When he wasn’t talking politics, he regaled his audience of Sangamotown residents, who had gathered to watch the construction of the flatboat, with humorous yarns and witty stories.

By mid-April, Lincoln and the others—Offutt, Hanks, and Johnston—launched the flatboat and sailed down the Sangamon River toward Beardstown. At New Salem, however, a mill dam forced them to halt, for while the flatboat’s bow passed smoothly over the dam, the remainder of the vessel did not clear the barrier, and in an instant the boat became stuck, hung up on the dam and suspended over its edge in the middle of the turbulent river. In what would become one of the most famous episodes of his life, Lincoln jumped off the boat into the cold water and tried to free the vessel by prying it over the obstacle. In the words of one New Salem witness, Lincoln strained “every nerve to push the boat off the dam,” but his efforts failed.

Nothing would dislodge the boat, and the crew noticed that with the bow high in the air and protruding over the dam, the stern had dipped into the river and was taking on water. The situation was now more dire than it had been. It was at that moment, as the circumstances worsened, that Lincoln thought of a practical solution to the problem. Through the deep water of the mill pond created by the dam, he either waded or swam to the riverbank, inquired among the crowd of spectators, and walked to a carpenter’s shop in the village, where he borrowed an augur. Then he returned to the river, found a small ferry boat that wasn’t being used at the moment, and directed the effort to offload to the ferry (and thus to shore) as much of the flatboat’s cargo as the crew could manage. Onboard, Lincoln used the augur to drill a hole in the bow’s hull. By now he was fully in command of the flatboat’s rescue. He directed the crew into the water, and the three men lifted the stern of the boat out of the river, by which means they drained out through the bow hole all of the water that had seeped into the boat. Somehow (none of the surviving accounts are very detailed) Lincoln plugged the bow hole, probably with a wooden dowel sealed with pitch or tar, which he must have obtained from the watching villagers. Finally, with everyone’s clothes soaking wet and their bodies shivering, the men pushed the flatboat over the dam. Later the crew reloaded the flatboat. Lincoln’s ingenuity impressed everyone—Offutt, the onlookers, and everybody else who later heard about it. In fact, the story became something of a legend among the citizens of New Salem.

With the boat dislodged and reloaded, Offutt and his crew set off again down the rushing Sangamon. Just north of Beardstown, the Sangamon met the Illinois River, and the flatboat, finally leaving the Sangamon behind, picked up speed as it headed westward toward the Mississippi. North of Alton, Illinois, the flatboat slipped smoothly into the mighty river, came about, and pointed its bow south toward the Crescent City. For the second time in his life, Lincoln sailed the great river, looking for adventure and hoping for money in his pockets. Just like all the rivers in the West this spring, the Mississippi rose to its banks, fed by the thaw of snow in the mountains and the surging estuaries that carried water, mud, and silt along its pulsating ambit. Flatboats and keelboats skimmed along the water’s surface, and steamboats, chugging and puffing, worked their way down river and up—a grand flotilla of commerce and mobility.

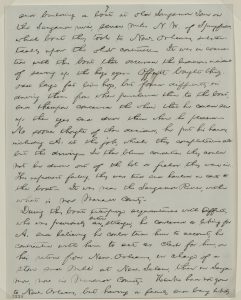

Coming to St. Louis, the crew tied up the flatboat at one of the countless wharves along the city’s edge, and it was there that the mystery of Lincoln’s second trip to New Orleans enters muddy ground. Some thirty years after the fact, during the presidential campaign of 1860, Lincoln claimed that Offutt’s flatboat paused in St. Louis so that John Hanks could be put ashore. Hanks, said Lincoln, wanted to turn back because he wished not “to be detained from home longer than at first expected.” Hence, according to Lincoln, Hanks did not go to New Orleans with the others.

But there is something distinctly peculiar about Lincoln’s assertion. Unlike John D. Johnston, who left Offutt’s employ before construction of the flatboat had been completed and rejoined the crew after the vessel had been launched, Hanks had remained on hand for the whole endeavor, and Hanks’s own accounts of his participation in the journey do not mention his departure at St. Louis; as a matter of fact, Hanks stated that he remained on board the flatboat until it reached New Orleans and then returned to Illinois with Lincoln. Is it possible that Lincoln’s memory failed him? Or is it at all likely that Hanks prevaricated about visiting New Orleans with the rest of the crew? Is the more credible witness Lincoln or Hanks?

Lincoln’s version has been generally taken at face value, if only because he seemed to have no reason to fabricate Hanks’s departure or falsify the facts. Yet Hanks, without knowing about Lincoln’s comment, claimed during two separate interviews he gave to Lincoln’s former law partner William H. Herndon (one in June 1865 and the other in 1865 or 1866), that he did, in fact, visit New Orleans with Lincoln and the others. Apart from this detail of the flatboat journey, Hanks’s overall testimony has been accepted as reliable, often filling in details about Lincoln’s early life in Illinois that would otherwise have remained unknown. Why should his recollections about the New Orleans trip be called into question?

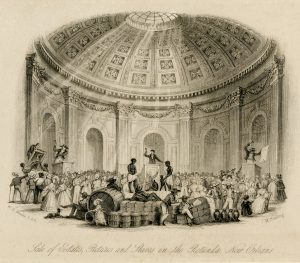

The most important doubt centers on Hanks’s declaration, made in one of his interviews with Herndon, that Lincoln reacted negatively to the slave auctions and to the treatment of slaves that Offutt’s crew witnessed in the Crescent City. In an obvious overstatement, Hanks asserted that Lincoln “formed his opinions of Slavery” after seeing firsthand the brutality of the peculiar institution. But if Hanks left the flatboat at St. Louis before Offutt and the others reached New Orleans, how could he possibly know about Lincoln’s response to what was seen in the city’s slave markets? Based on this conflicting evidence, some historians surmise that Lincoln may have told Hanks about his emotional reactions once the two men had been reunited in Illinois. But Hanks told Herndon definitively that he went with Offutt and the others to New Orleans. In an 1887 letter to Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s co-author of a Lincoln biography, Hanks tried to clarify his earlier testimony by saying that Lincoln actually communicated his antislavery sentiments to John D. Johnston, his fellow crewman and stepbrother. Unfortunately for posterity, Hanks’s letter is garbled and nearly inarticulate (he was illiterate, and someone must have written the letter for him). His precise words to Weik were: “It was his step Brother he mad[e] that remark to. his name was John Jonson[.] I was not at the sail at the time.”

Hanks was referring specifically to an alleged statement that Lincoln made after viewing the harshness of slavery in New Orleans: “By God, boys, let’s get away from this. If ever I get a chance to hit that thing [i.e., slavery], I’ll hit it hard.” Herndon said that he got the statement from Hanks, who quoted Lincoln during an interview, but Herndon’s extant interview notes contain no such statement. One could surmise that John D. Johnston gave Lincoln’s statement to Hanks, which seems to be what Hanks was trying to explain in his letter to Weik. But Hanks implied that the statement was made by Lincoln to Johnston on board a vessel (“sail”), perhaps meaning the steamboat that the crew took from New Orleans to St. Louis on the return trip. If so, then the statement makes no sense, since it is phrased in such a way to suggest that Lincoln said it while watching events transpire in the slave market and requesting his friends to leave the marketplace. More to the point, Hanks claimed in an interview with Herndon that Lincoln’s reaction to the slave market “was silent from feeling—was Sad.” From this we are led to believe that Lincoln said nothing at all about the institution of slavery or the treatment of slaves in the New Orleans slave market, but rather took on an expression of sadness caused by what he saw as a slave coffle passed by, perhaps on its way to the auction pens.

None of this means that Lincoln did not utter the statement that Herndon attributed to him. It’s possible that Lincoln said something along those lines to Johnston while the crewmen walked the streets of New Orleans and that Johnston later repeated the words to Hanks who, in turn, told them to Herndon in an interview that went unrecorded or went missing over the years. But all this third- and fourth-hand information about such questionable evidence makes it seem unlikely Lincoln said any such thing about hitting slavery hard in 1831. Complicating matters is the fact that Hanks, in a newspaper interview given in 1881, when he was seventy-nine years old, insisted that he and Lincoln had made “two different trips to New-Orleans” on flatboats in the early 1830s. Other sources also assert that Lincoln made a total of three flatboat voyages to New Orleans. It is certainly possible that Lincoln went to New Orleans on a third trip, but he never mentioned more than two voyages made by flatboat down the Mississippi, once in 1828 and again in 1831. So it seems fair to say, given the lack of corroborative sources, that Lincoln did not take a third flatboat trip to the Crescent City.

Nevertheless, Lincoln’s own statement about Hanks leaving the flatboat in St. Louis and returning to Illinois—given the weight of Hanks’s insistence that he remained in Offutt’s employ all the way to New Orleans—grows weak under close examination. If Hanks did return to Illinois as Lincoln claimed, why did he not turn back at Alton or ask to be dropped off, at the very least, on the Illinois side of the Mississippi, which would have made his trip home all the easier? Lincoln had no reason in 1860 to make up the story about Hanks leaving the flatboat in St. Louis. But it is interesting that his statement appears in only one of his autobiographical sketches for the campaign of 1860, the one prepared for John L. Scripps. What’s more, Scripps inexplicably asserted that he had “not been put in possession of any of the incidents connected with this trip,” when indeed he had been, and decided for whatever reason to leave out Lincoln’s reference to Hanks from the published campaign biography.

As for Hanks making the round trip to New Orleans and back, Herndon never doubted that Hanks had done just that. He also accepted that Lincoln swore to hit slavery hard after seeing a slave auction because, as Herndon put it, “I have also heard Mr. Lincoln refer to it himself”—the “it” being his reaction to the slave market or, possibly, to his remark about hitting slavery hard, or both. Mentioning Hanks as his source, Herndon professed that Lincoln at the slave market was specifically horrified by watching “a beautiful mulatto girl, sold at auction. She was felt over, pinched, trotted around to show the bidders that said article was sound, etc. Lincoln walked away from the sad, inhuman scene with a deep feeling of unsmotherable hate. He said to Hanks this: ‘By God! if I ever get a chance to hit that institution, I’ll hit it hard, John.’” Herndon added that “John Hanks, who was two or three times examined by me, told me the above facts about the negro girl and Lincoln’s declaration. There is no doubt about this.” But Hanks said nothing of the kind in the notes Herndon kept of his interviews, in the letter Hanks sent to Weik in 1887, or in any of the surviving newspaper interviews Hanks gave to the press.

As if all this were not enough to muddy the record of Lincoln’s second trip to New Orleans, Herndon disclosed yet another episode that took place while Lincoln and the Offutt crew were there. In Herndon’s words, “when Lincoln went down to New Orleans in ’31 he consulted a Negress fortune teller, asking her to give him his history, his end and his fate; she told him what it was, according to her insight, which was no insight at all but simply a fraud to make money. It may be true that the Negress did believe that she was inspired or empowered to see the visions and end of all mortals. This story is said to be true. I cannot vouch for it, and yet it is told me and it is quite likely the case.” In another version of the story, the fortune teller predicts to Lincoln: “You will be President, and all the negroes will be free.”

Finally, the peculiar nature of the autobiography adds to the mystery. In early June 1860, after his nomination by the Republican Party, Lincoln received numerous requests for biographical information and statements of his political policies. He turned down those requests by preparing forms that explained he could not possibly answer every individual query. Lincoln intended his brief autobiography to aid a handful of authors who were writing campaign biographies of him. But why he included details about so many things, like his flatboat trips, and excluded other crucial matters, like the names of his children, is not evident. The document is something of a hodge-podge, lacking a strict chronological order to the events he recounts and, one suspects, describing other experiences out of proportion to their real importance in his life, such as naming all of his school masters in Kentucky and Indiana, but admitting that he only attended those schools “by littles.”

Among the autobiography’s many oddities is the inclusion of his fellow crewmen by name on the flatboat in 1831. In that context, his remark about John Hanks’s departure at St. Louis appears all the more strange. While building the flatboat at Sangamotown, John Johnston—whom Lincoln always regarded as lazy—left Lincoln and Hanks to finish the job, but later returned to complete the trip to New Orleans. Lincoln made no mention of that, missing a fine opportunity to embarrass his stepbrother. For that matter, Lincoln himself quit the venture at Beardstown, when Offutt and Hanks went on a drinking spree, and walked all the way back to Sangamotown, where Offutt later found him. Smooth talker that he was, Offutt successfully begged Lincoln to rejoin the crew, promising that there would be no more carousing as they floated down the Mississippi. No doubt Lincoln was too ashamed to recount that episode in his autobiography. It also seems unusual that Lincoln made no explicit reference to his impression of New Orleans, which must have been favorable enough for him to hope he could stay on there and find work cutting cordwood for steamboats. When, however, Hanks and Johnston both took sick at the end of the month they all spent in the city, Lincoln decided his best course would be to accompany his mates home to Illinois.

Out of this morass of evidence, like a gummy, circuitous Louisiana bayou, it is nearly impossible to determine what precisely occurred during Lincoln’s second visit to New Orleans. But after weighing this evidence, I have reached several conclusions that I’ve used to guide my understanding of the flatboat trip and the crew’s layover in New Orleans: 1. Hanks did not leave the flatboat in St. Louis (thus Lincoln’s memory must have failed him about Hanks’s departure; for his part, Scripps detected that something was amiss and omitted Lincoln’s reference to Hanks); 2. one of Hanks’s accounts of the trip—i.e., the one given in an interview conducted by Herndon, ca. 1865–1866—can be accepted as authentic and credible; 3. other claims about the New Orleans trip (even those attributed to Hanks)—such as Lincoln’s promise to hit slavery hard whenever he might get the chance, the story of the slave girl on the auction block, and the far too prescient remarks of the fortune teller—could well be true but suffer, in my estimation, from an excessive dose of Victorian melodrama.

Unless new sources come to light about Lincoln’s second voyage to New Orleans, it’s unlikely that the mystery surrounding whether John Hanks made the entire round trip or that he quoted Lincoln accurately can be conclusively solved. At this great distance from the spring of 1831, the appearance of corroborating evidence seems about as doubtful as the Mississippi River flowing backwards.