The Intellectual Milieu of Abraham Lincoln

The Intellectual Milieu of Abraham Lincoln

By Allen C. Guelzo

Abraham Lincoln was not a philosopher, or even what we might today call an intellectual. “Politics were Lincoln’s life,” William Henry Herndon told Jesse Weik in 1887, “and newspapers were his food.” Yet, in almost the same breath, Herndon acknowledged that “we used to discuss philosophy,” that Lincoln “knew much of the law of Political Economy & the Social Science,” and that above all, Lincoln was “intensely thoughtful—persistent—fearless and tireless in thinking” and “lived in his reason and reasoned in his life.” He had intellectual hobbies that only occasionally peeked-out from the wings of his professional and political life, especially “political Economy—the study of it,” and Herndon listed a virtual syllabus of 19th-century writers on the subject which Lincoln “digested and assimilated” – John Stuart Mill, Henry Carey, John Ramsey McCullough and Francis Wayland.[1] (He would, in fact, lift an entire section from Mill’s Principles of Political Economy and write it into one of his more famous speeches, the address to the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society in 1859, and re-use Wayland’s if A, on the ground of intellectual superiority, have a right to improve his own means of happiness…. to produce his 1854 syllogism If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B)….[2]

Limited as Lincoln’s formal education had been, he had “also studied Natural Philosophy” as well as “Astronomy, Chemistry” from whatever other books he could find “from which he could derive information or knowledge,” and in 1855, Herndon remembered that he was so intrigued by the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s popular serial, The Annals of Science: Being a Record of Inventions and Improvements, that “he instantly rose up and said that he must buy the whole set.”

Herndon told Francis Carpenter that, before leaving for Washington in 1861, Lincoln had sent “to my private residence a box ful of his books – mostly political” but including “some valuable literary works—Byron—Goldsmith—Locke—Gibbon &c.”[3] So when the English lawyer George Borrett called on him at the Soldiers’ Home in the summer of 1864, Lincoln not only “launched off into some shrewd remarks about the legal systems of the two countries, and then talked of the landed tenures of England,” but “next turned upon English poetry, the President saying that when we disturbed him he was deep in [Alexander] Pope.”[4] And he would later surprise John Hay with “a little indulged inclination” for “philology” and a deep acquaintance with Shakespeare. “Some of Shakespeare’s plays I have never read,” Lincoln admitted in 1863, but “others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth. It is wonderful.”[5]

While this will re-inforce Leonard Swett’s warning that “any man who took Lincoln for a simple minded man would very soon wake [up] with his back in a ditch,” it does not go very far toward placing Lincoln on the larger intellectual map of his times.[6] For that, we have to consider a wider milieu, and Lincoln’s place in it. Oddly, for much of the 20th century, there was very little agreement that Lincoln’s America had much in the way of such a milieu. The great American historian (and Librarian of Congress) Daniel Boorstin described Americans as do-ers rather than thinkers, pragmatists rather than philosophers, who “focused on immediate, changing, and unpredictable needs… They did not pursue the absolute, nor expend their thinking on doctrinal quibbles.” In every aspect of American life, “ideology was displaced by organization. Sharp distinctions of thought and purpose were overshadowed by the need to get together on…common purposes.” Even Lincoln’s fellow-lawyers proceeded “warily and undogmatically from case to case,” Boorstin claimed, and were “rich in the prudence of individual cases but poor in theoretical principles.”[7]

European observers tended to agree, although not in Boorstin’s enthusiastic tones. In the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville was dismayed to find that “there is no country in the civilized world where they are less occupied with philosophy than the United States.” And not only philosophy – less occupied with theology, with political theory, with “fewer great artists, illustrious poets, and celebrated writers” than in Europe. This, Tocqueville concluded, was the inevitable result of America’s democratic politics. In democracies people have only the shallowest of ideas, and tend to be “tightly chained to the general will of the greatest number.”[8]

But both Tocqueville and Boorstin were looking through the wrong end of the telescope, for the most obvious fact about American democracy was, as Lincoln put it, that it was founded on a philosophical proposition, “that all men are created equal.” This founding was itself a marker of a tremendous intellectual upheaval known as the Enlightenment, in which not only a political order but an entire way of understanding the universe were dramatically re-written. From the Middle Ages, western Europeans had understood the physical world as a hierarchy: from the Earth on up to the highest heavenly realms, all material things stood in an orderly and graded relationship to each other. This applied to the social and political world as well. Societies and kingdoms existed as social pyramids, with mutually-supportive layers of kings, nobility and commoners in strictly top-down fashion.

But beginning in the 1600s, a revolution in scientific thinking overturned the fixed hierarchies of the heavens and earth and substituted natural laws as the explanations for movement and order in the physical world; and in the hands of the eighteenth century’s political philosophers – Locke, Montesquieu, Beccaria – the old pyramids were challenged by theories of natural rights which everyone held equally. It was from this Enlightenment that the American Revolution sprang.[9]

Lincoln was born at almost the tail end of the Enlightenment, in 1809. But his entire mental life was wrapped around the Enlightenment principles that had animated the American founding. “All the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated, and were given to the world from this hall in which we stand,” he said at Independence Hall, on his way to his inauguration in 1861. “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” Government was rooted, not in the authority of superiors in a hierarchy, but in the consent of all the governed, as equals bearing equal natural rights. “No man,” Lincoln said in his great Peoria speech of October 1854, “is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle — the sheet-anchor of American republicanism.”[10]

But more than simply embracing the politics of the Enlightenment, Lincoln also espoused the Enlightenment’s rejection of arbitrary intellectual authorities of any kind, starting with religious skepticism. No writers held more charm for the twenty-something Lincoln than the paladins of Enlightenment religious doubt, “Tom Pain & [Constantin] Volney,” leading the young Lincoln to go “further against Christian beliefs — & doctrines & principles than any man.” For Lincoln, neither religious authority nor religious enthusiasm, but reason was the guiding light to truth. “Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence,” he declared in 1838, and he irritated the devout of Springfield in 1842 by describing as a “Happy day, when, all appetites controled, all passions subdued, all matters subjected, mind, all conquering mind, shall live and move the monarch of the world. Glorious consummation! Hail fall of Fury! Reign of Reason, all hail!”[11] This was a skepticism which experience and prudence would teach Lincoln to temper over the years. But it was never wholly effaced, either. He would not even attempt to govern his rambunctious children by authority. “It is my pleasure that my children are free, happy and unrestrained by parental tyranny,” he explained. “Love is the chain whereby to bind a child to its parents.”[12]

What reason taught Lincoln in particular was two-fold: that minds were impressed with sensations that corresponded to external realities (which was John Locke’s doctrine in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1689) and that minds were effectively passive in receiving and acting on those sensations. “He adopted Locke’s notions as his system of mental philosophy,” Herndon wrote, and “held that reason drew her inferences as to law, etc., from observation, experience, and reflection on the facts and phenomena of nature.” This made him “a pure sensationalist” and “a materialist in his philosophy.” There was, in Lincoln’s understanding, no room for “dualism” – the parallel existence of material and spiritual substance, with free will and free choice located in the spiritual realm.[13]

A disbelief in free will occupied a central place in Lincoln’s mental scaffolding. In part, it surely owes something to the radical Calvinism of the Separate Baptists to whom his parents belonged and in whose fellowship Lincoln grew up in Indiana. But Lincoln’s mature ideas on the absence of free will have a decidedly naturalized cast which he shared with many of the prominent Enlightenment voices whose names surface in descriptions of Lincoln’s reading – Edward Gibbon, whose Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776) he borrowed from William Greene in New Salem, and David Hume, whose Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) was lent to him by Herndon. “There was no freedom of the will,” Lincoln informed Herndon. Since all that existed was material substance, and since material substance was governed entirely by natural laws, then there was no room for human wills to upset the causal chains that connected one event to another. What Lincoln called (in terms similar to Hume) the “Doctrine of Necessity” was defined entirely by a kind of Pavlovian response to motives – “that is, that the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control.” This did not mean that people were will-less zombies. But it did mean that the operation of the will was a response to motives, which “moved the man to every voluntary act of his life.”[14]

What the wise politician did, then, was to appeal, not to authority, but to self-interest in order to stimulate the responses of his constituents. And Lincoln did not hesitate to make this appeal central to his handling of emancipation and the recruitment of black soldiers. In the public letter, defending emancipation, which he wrote for James Cook Conkling in 1863, Lincoln pointedly asked what Northerners wanted. “You desire peace; and you blame me that we do not have it. But how can we attain it?” Only by suppressing the Confederate rebellion. And what will achieve that? The application of as much force as possible – including the force lent by recruiting blacks as soldiers. “I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union.” But to motivate that recruitment, isn’t it necessary to offer a sufficient motivation? “Negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive, even the promise of freedom.”[15]

What reason taught Lincoln about a natural politics, also described for him what a natural economics ought to look like, and the Enlightenment fostered in Lincoln as unfettered a notion of commerce as it did of government. For centuries, economies had been governed by kings, and organized as monopolies to be put into the hands of the nobility as rewards for faithful service. Wealth was thought-of only in terms of landownership, and the rents to be collected from peasant tenants; making a living in towns from exchange and production was dismissed as “low employment.” “The exercise of merchandise hath been (I confess) accounted base and much derogating from nobility,” admitted the poet Henry Peacham, even if he had to concede that “Common-wealths cannot stand without Trade and Commerce, buying and selling.”[16]

The Enlightenment tore loose from this completely, glorifying commerce and the merchant classes as the engines of real (as opposed to arbitrary) benefit to societies. “Why should not the knowledge, the skill, the expertness, the assuidity, and the spirited hazards of trade and commerce, when crowned with success, be entitled to…those flattering distinctions by which mankind are so universally captivated?” asked Samuel Johnson, the great dictionary-maker, in 1765. “There are few ways in which a man can be more innocently employed than in getting money.” It delighted Joseph Addison (of The Spectator) in 1711 “to see…a body of men thriving in their own private fortunes, and at the same time promoting the public stock; or…raising estates for their own families, by bringing into the Country whatever is wanting, and carrying out of it whatever is superfluous.”[17]

It delighted Lincoln, too. “Twenty-five years ago, I was a hired laborer,” he said, in a rare moment of reflection on his poor-boy past. But in America, there were no kings or nobility to hoard the nation’s wealth for themselves and their favorites. In a world devoid of hierarchy, “the hired laborer of yesterday, labors on his own account to-day; and will hire others to labor for him to-morrow.” This is because “advancement — improvement in condition — is the order of things in a society of equals.” It was this which drove Lincoln, from his earliest political awakenings, into the Whig Party, since the Whigs and their great figurehead, Henry Clay, were preeminently the champions of commercial development and a national marketplace system, supported by government-sponsored banking, infrastructure creation and protective tariffs.[18]

In this way, Lincoln’s life paralleled the flowering of Enlightenment economic thought in England and Europe, especially as it was represented by the 18th-century Scots, Adam Smith and John Ramsay McCullough (whom Herndon remembered that Lincoln had “digested and assimilated”), and by the 19th-century ‘Manchester School’ of Richard Cobden and John Bright, and by John Stuart Mill, John Elliott Cairns and Goldwin Smith. Cobden, who had met Lincoln in the 1850s while in the United States, saw his task to be “one of the leading executors of that legacy of economic science which the Scottish philosophers of the last century had bequeathed,” and to denounce “meddling with any of our commercial arrangements” by government, “which was the creature of monopoly.” Cobden “steadfastly opposed” all favors to “political exclusion, to commercial monopoly and restriction, to the preponderance of a territorial aristocracy in the legislature.” Bright, whose portrait Lincoln kept on the mantelpiece of his White House office, was hailed as “the undisguised champion of American Institutions, and staunch supporter of Republican principles.”[19] Lincoln was conscious enough of this transatlantic connection to fix on slavery as the principal embarrassment the United States suffered as the world’s chief exponent of Enlightenment principles, since “it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world‑‑enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites‑‑causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity.”[20]

The American Republic was the Enlightenment’s first offspring as a nation. But Lincoln only arrived on the American scene as the Enlightenment’s hold on America was beginning to slip, first to a rival (in the form of evangelical Protestantism) which had almost as good a claim to being America’s intellectual parent, and second to an outright challenger in the form of Romanticism, whose antagonism to Enlightenment ideas would help bring the country to civil war.

The English settlements which grew to become the United States had not been founded by plan. Almost all of them had been originally planted by religious exiles from England – Puritans, Quakers, Catholics – whose interests remained strong enough to be reckoned with in the new republic. The leadership of the American Revolution – Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin — might have been deeply enamored of the Enlightenment, but much of the rest of the nation retained habits of religious practice which often sat in direct criticism of the Enlightenment. In the 1740s, a major Protestant religious revival known as the Great Awakening blew through American life like a hurricane, reminding its devotees that not reason but faith was the tie that bound people to God, and that the “religious affections” were a better barometer of one’s spiritual health than natural law. “True religion is evermore a powerful thing,” warned Jonathan Edwards, the most talented analyst of the Awakening, and its power “appears in the inward exercises of it in the heart.” And not only religion. “The Author of the human nature has not only given affections to men, but has made ‘em very much the spring of men’s actions.”[21] The power of the Awakening not only led to an explosion in the number of evangelical Protestant congregations between 1780 and 1860, but to the founding of a string of colleges – Princeton, Brown, Dartmouth, and even the otherwise secular University of Pennsylvania – which became the centers of American intellectual life in the early republic.[22]

Yet, the colleges and the Awakeners learned to make their peace with the Enlightenment. Reason might guide Americans in the constructing of their new political order, but virtue would be required to preserve its operations, and the leadership of the Awakening and its colleges was happy to suggest that they could provide the substance of a virtue which was at once both reasonable and religious. Francis Wayland, whom Lincoln so admired on political economy, offers a perfect example of this. A Baptist minister and president of Brown University, Wayland asked his students to notice that all change in the universe follows a uniform pattern. When they did, they would discover an analogy: that minds follow those same patterns. Such pervasive regularity logically required the existence of a Law-Giver for both physical and mental behavior – although, happily, the process of discovering that Law-Giver is as reasonable as any Enlightenment philosopher could require. “It is only when…bursting loose from the littleness of our own limited conceptions, we lose ourselves in the vastness of the Creator’s infinity, that we can rise to the height of this great argument and point out the path of discovery to coming generations.”[23]

Morality was thus not an accident, a social convention, or an illusion; it was a conscious law of the mind, and like the laws of physical science, it instructed people in the laws of character development, social relationships, politics, economics, and their spiritual duties to God. This “common sense” morality was the perfect prescription for an Enlightenment republic: it yielded moral laws without compelling people to embrace Protestant theology. But it allowed Protestant Christians like Wayland to slip the fundamentals of Christian morality into public affairs without the hubbub of revivalism, and thus let a kind of low-level evangelism operate on the republican masses. That, in turn, allowed Lincoln (like many of Lincoln’s fellow-Whigs in the 1830s and Republicans in the 1850s) to strike up alliances with evangelical Protestants. Both Lincoln and the evangelicals were, after all, alike in the business of self-transformation, Lincoln economically and the evangelicals spiritually. And so he grew increasingly careful to subdue his free-thinking impulses, and even to suggest that the “Doctrine of Necessity” was the “same opinion…held by several of the Christian denominations.”[24]

But Lincoln would never actually join them. “His nature was not at all enthusiastic,” remembered White House staffer William O. Stoddard, “and his mind was subject to none of the fevers which pass with the weak and shallow for religious fervor, and in this, as in all other things, he was too thoroughly honest to assume that which he did not feel.” The war years, and their terrible toll, would force Lincoln to resort increasingly to religious explanations – especially for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation – but never made him into an outright believer. At least, said Orville Hickman Browning, Lincoln shed any temptation to be “a scoffer at religion. During our long and intimate acquaintance and intercourse I have no recollection of ever having heard an irreverent word fall from his lips.” And the truce that “analogy” offered between evangelical Protestantism and Enlightenment reason allowed Lincoln to welcome the support of Northern churches, even as he fended-off their requests for more explicit recognition of Christianity in public life (as in the appeal by the National Reform Association in 1864 to have the Constitution amended to insert a reference to God, humbly acknowledging Almighty God as the source of all authority and power in civil government).[25]

The restlessness of evangelical Protestantism was a domestic and largely benign feature of America’s intellectual geography, and willing to live in at-least-uneasy yoke with the republic’s Enlightenment political and economic rules. The same could not be said for Romanticism, which was an international and irreconcilably hostile response to the Enlightenment. The fuel of the Romantic revolt lay in the Enlightenment’s over-confidence in ascribing orderliness to the universe, and reason’s capacity to discern it. To the promoters of the Enlightenment, reason brought clarity, balance and order. Enlightenment art, according to Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Art (1758) cultivated “noble simplicity and sedate grandeur.” Anything which “partakes of fancy or caprice…is incompatible with that sobriety and gravity which are peculiarly the characteristics of this art,” added Sir Joshua Reynolds in the tenth of his Discourses, on sculpture. Not passion, but “the beauty of form alone, without the assistance of any other quality, makes of itself a great work, and justly claims our esteem and admiration.”[26]

The problem was that orderliness and reason could very easily produce blandness, ennui and boredom, too. Like Dickens’ Thomas Gradgrind, the Enlightenment seemed ready “to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to.” Even worse, the Enlightenment’s hope that nature could be reduced to a predictable machinery faltered in the face of unprecedented (and inexplicable) natural disasters like the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. So, when the poet William Blake read Reynolds’ Discourses, he erupted, “Passion & Expression is Beauty itself,” and to Reynolds’ condemnation of “fancy,” Blake retorted, “If this is True, it’s a devilish Foolish Thing to be an Artist.” The Romantics sought release from the trammels of reason, turning for relief and adrenalin to the pursuit of the sublime, which Edmund Burke, in his Philosophical Inquiry Into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) defined as whatever conveyed feelings of astonishment, terror, obscurity and power.[27] Romantic art discarded the balance and symmetry of Reynolds and Winckelmann and turned instead to J.R.W. Turner’s swashes of color and the dark violence of Eugene Delacroix; Romantic music set aside the polite orderliness of Haydn and Mozart in favor of the storm and lightning of Beethoven, Berlioz and Wagner; Romantic literature, like Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, praised the value of medieval chivalry; Romantic history must be a history of races, races and nationalities.

Those races and nations most often glorified by Romantic politics were monarchies and empires, while Romantic economics gushed in praise over social solidarity and organic mutuality and spat in contempt at “trade.” In the Romantic imagination, human societies should not be considered as collections of self-interested individuals, but as organisms whose component parts depend on each other’s co-operation. The German Romantic historian, Johann Herder, spurned the notion that humanity should be considered as a universal system of individuals, all bearing equal rights, and mourned for the days when

generations and families, master and servant, king and subject, interacted more strongly and closely with one another; what one is wont to call ‘simple country seats’ prevented the luxuriant, unhealthy growth of the cities, those slagheaps of human vitality and energy, whilst the lack of trade and sophistication prevented ostentation and the loss of human simplicity in such things as sex and marriage, thrift and diligence, and family life generally.

His fellow-German poet, Heinrich Heine, had nothing but contempt for American ideas of freedom. America, to Heine, was a “huge prison of freedom,” with “neither princes nor nobles” but where “all are equally churls.”[28]

For all of Romanticism’s complaints, Lincoln had no sympathetic ear whatsoever. Romantic literature left him unmoved. “It may seem somewhat strange to say,” he admitted to Francis Carpenter, “but I once commenced Ivanhoe, but never finished it.” He had read Lord Byron, the arch-Romantic of English literature, in his youth, but little of it shows up in Lincoln’s later references; his appreciation for American Romantic poets was, according to Noah Brooks, limited to the elder Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Birds of Killingworth and A Psalm of Life.[29]

Neither did Lincoln have much of the Romantic adulation for nature. His solitary recollection of his Kentucky boyhood was an unpromising remembrance of how “sometimes when there came a big rain in the hills, the water would come down through the gorges and spread all over the farm” and “washed ground, corn, pumpkin seeds and all clear off the field.” As a state legislator, his greatest use for nature was to force it to yield “good roads” and “navigable streams” for the benefit of trade. Through “internal improvements” of this sort, “the poorest and most thinly populated countries would be greatly benefitted.” Nor did anything sublime strike him about Niagara Falls when he first saw it in 1848. “What mysterious power is it that millions and millions, are drawn from all parts of the world, to gaze upon Niagara Falls?” Lincoln asked himself. “There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any intelligent man knowing the causes, would anticipate, without [seeing] it.”[30]

Herndon thought he was even more prosaic about Niagara in years afterward. When Herndon returned from New York “some time after” by way of the Falls, he “was endeavoring to entertain my partner with an account of the trip, and among other things described the Falls.”

After well-nigh exhausting myself in the effort I turned to Lincoln for his opinion. “What,” I inquired, “made the deepest impression on you when you stood in the presence of the great natural wonder?” I shall never forget his answer, because it in a very characteristic way illustrates how he looked at everything. “The thing that struck me most forcibly when I saw the Falls,’ he responded, “was, where in the world did all that water come from?” He had no eye for the magnificence and grandeur of the scene, for the rapids, the mist, the angry waters, and the roar of the whirlpool, but his mind, working in its accustomed channel, heedless of beauty or awe, followed irresistibly back to the first cause. It was in this light he viewed every question.[31]

But Lincoln’s most decisive differences from the Romantics lay, not in aesthetics, but in politics and economics. He had no concept of the American nation as a Germanic-style Volk. In the eulogy he delivered in Springfield in 1852 for Henry Clay, Lincoln spoke of Clay – and indirectly, for himself – as a man who “belonged to his country” but also “to the world,” who “loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country; and he burned with a zeal for its advancement, prosperity and glory, because he saw in such, the advancement, prosperity and glory, of human liberty, human right and human nature.” Lincoln persisted in viewing national identities as mere surface phenomena compared to the fundamental commonality everyone enjoyed through the equality of natural rights articulated in the Declaration of Independence. “We have…among us,” he said at the outset of 1858 senatorial campaign which would make him nationally famous, “men who have come from Europe — German, Irish, French and Scandinavian men — that have come from Europe…and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things.” Show them the history of the Revolution and its battles and its leaders, and they will be unable to “carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us.” However, “when they look through that old Declaration of Independence” and “find that those old men say that ‘We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal,’” there is an instinctive response, a logical sympathy which effaces mere nationalism and racialism. “And then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.” This did not make Lincoln a modern racial egalitarian – there were some prejudices that not even the Enlightenment had been very successful in conquering – but it did make him reject utterly the idea that membership in one race entitled its holders to lord it over others.[32]

Lincoln had no nostalgic yearnings for bygone eras of hierarchy and solidarity, when

The Greatest owed connection with the least,

From rank to rank the generous feeling ran

And linked society as man to man….

“Free society,” he said in 1860, knows no ranks. Anyone can make and re-make their condition as they please, since “there is no fixed condition of labor.” He had once been a “hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat boat”; he had, by the Romantic reckoning, really “used to be a slave.” But “now I am so free that they let me practice law,” which, in America, is “just what might happen to any poor man’s son.” He wanted “every man to have the chance” to do likewise, and he was willing to step far enough outside the constructing circle of race to add, “and I believe a black man is entitled to it” as well.

The passing of monarchy and hierarchy were nothing to be regretted, since monarchy was, in essence, nothing but slavery. “They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle,” he said in his final debate with Stephen Douglas in 1858.

The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.[33]

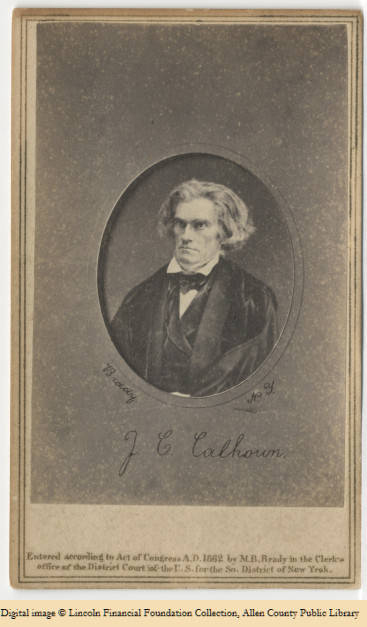

But slavery had its American defenders, the Enlightenment and the Declaration notwithstanding, and not surprisingly, the justifications offered for slavery – and especially slavery based on race – were drawn entirely from the Romantic playbook. Slavery’s greatest ideologue, John C. Calhoun, praised the South’s plantations as idyllic, self-contained villages, “a little community, with the master at its head, who concentrates in himself the united interests of capital and labor” and where “capital and labor is equally represented and perfectly harmonized.” In Calhoun’s Romanticized vision, it was entirely appropriate to enslave black people on the accidents of physical difference and dismiss universal natural right. “Instead…of all men having the same right to liberty and equality,” wrote Calhoun, rights are social conventions, to be handed out as “high prizes” to those races “in their most perfect state.” And far from this creating contention and oppression, Calhoun insisted that “the existing relations between the races in the slaveholding states” has “been a great blessing to both of the races.” No one should be deluded by the false premises of the Declaration of Independence, Calhoun warned.

If our Union and system of government are doomed to perish, and we are to share the fate of so many great people who have gone before us, the historian … will trace it to a proposition, which originated in a hypothetical truism, but which as now expressed and now understood is the most false and most dangerous of all political errors. The proposition to which I allude has become an axiom in the minds of a vast majority on both sides of the Atlantic, and is repeated daily from tongue to tongue as an established and incontrovertible truth; it is that ‘All men are born free and equal’ …As understood, there is not a word of truth in it….

“All men are not created equal,” Calhoun announced, and with that, hierarchy made its return to the American scene.[34]

And not social hierarchy alone. George Fitzhugh, the Virginian whose Sociology for the South; or, The Failure of Free Society (1854) infuriated Lincoln when Herndon bought him a copy, declared that “Nothing can be found in all history more unphilosophical, more presumptuous” than “the infidel philosophy of the 18th century.” The worst aspect of that philosophy was the pretense of “Political Economy” captured by “in the phrase, ‘Laissez-faire,’ or ‘Let alone,’” which included not only the economic self-propulsion Lincoln preached, but “free competition, human equality, freedom of religion, of speech and of the press, and of universal liberty.” All these, Fitzhugh stigmatized as “a system of unmitigated selfishness,” since “the disparities of shrewdness, of skill and business capacity, between nations and individuals, would, in the commercial and trading war of the wits, rob the weak and simple, and enrich the strong and cunning.”[35]

In the place of “the doctrines of individuality,” Fitzhugh lauded socialism as the newest version of economic solidarity, and, in truth, he added, “socialism is already slavery in all save the master.” (Better still, “we slaveholders say you must recur to domestic slavery” as “the oldest, the best and most common form of Socialism.”) The genius of Southern slavery was that (as James Henry Hammond explained) Southerners understood that slavery was inevitable, and that one class had to be consigned permanently to the performance of what he called the “mud-sill” work of any society. “Fortunately for the South,” said Hammond, “she found a race adapted to that purpose…a race inferior to her own, but eminently qualified in temper, in vigor, in docility, in capacity to stand the climate, to answer all her purposes. We use them for our purpose, and call them slaves.”[36]

Nor was this merely the talk of a handful of aggressive but marginal radicals, driven loony by race. “Society is a pyramid,” explained the editor of the Nashville Daily Gazette late in 1860. “We may sympathize with the stones at the bottom of the pyramid of Cheops, but we know that some stones have to be at the bottom, and that they must be permanent in their place.”[37] All across the slave South in the fifty years after the Revolution, hierarchy was stealthily supplanting the Enlightenment in a number of forms, consigning whites as well as blacks to fixed places in a social pyramid. First, slaveholding concentrated more and more economic power in fewer and fewer hands. Compared to the North, the states which would make up the Confederacy had few of the mechanisms of credit and mercantile services which the “hired laborer” could use for self-improvement. The state of New York alone had more banks than the entire future Confederacy; so did Massachusetts and Rhode Island, taken together. The Confederacy had only one city larger than 45,000 people (New Orleans, with 114,000), while New York City and Philadelphia each had a larger population than the six principal cities of the Confederacy combined. In the Northern states, the average size of farms ranged between 118 and 155 acres; in the slave states, the median farm was one thousand acres and larger, which more nearly approximated the landholdings of the British gentry, while in Louisiana, the average cotton plantation swelled to over 2400 acres.[38]

Concentrations of economic power then translated into concentrations of political power. In 1860, less than 2% of the future Confederacy (some 98,000 Southerners) owned three-quarters of all the slaves; yet, they ruled the legislatures of Southern state after Southern state. They, and not the aspiring “hired laborer,” gave direction to the Southern economy, so that railroad development in the South was overwhelmingly underwritten by state government dollars rather than private initiative. “The South, then, is to all intents and purposes an Aristocracy, nay, an Oligarchy,” concluded James Stirling, the heir of a Glaswegian merchant fortune who visited America in 1857, “for in addition to aristocratic feeling, there is also an anti-democratic inequality of fortune.” The South, complained Albion Tourgée, “was a republic in name, but an oligarchy in fact,” and Francis Lieber added, “the most prominent extremists” in the South for states’ rights were, in practice, “strongly inclined toward centralization and consolidation of power within their respective States.”[39]

By the time South Carolina seceded from the Union, Southerners were already beginning to talk about the re-introduction of some form of monarchy. “I am a Virginian, a monarchist,” declared John Esten Cooke, and in 1858, DeBow’s Review, the pre-eminent agricultural magazine of the South, was earnestly wondering whether monarchical government might not be superior to American democracy. “The nature of our Government is such as to render it short-lived,” and thoughtful Americans “would gladly exchange” it for “a wisely adjusted constitutional monarchy.” “From all quarters have come to my ears the echoes of the same voice,” wrote the British journalist William Howard Russell as he toured the South after the outbreak of the Civil War. “It may be feigned,” Russell allowed, but it said, “If we could only get one of the royal race of England to rule over us, we should be content.” Russell had expected nothing of this sort in America, but he had no choice but to believe his own ears. “The admiration for monarchical institutions on the English model, for privileged classes, and for a landed aristocracy and gentry, is undisguised and apparently genuine. …We, it appears, talked of American citizens when there were no such beings at all.”[40]

We most often look upon the Civil War as a political and military conflict, and occasionally as an economic and a personal one, but only rarely as an intellectual one. And yet, in its most basic sense, the Civil War was a clash of philosophies, with the principles of the Enlightenment, as defended by Lincoln and the free-labor North, set upon by the aggressive assertion of Romanticism in the form of the slave Confederacy and the ineluctable attractions of hierarchy and solidarity. Lincoln and the Union triumphed in that case, and with that came the vindication of the Enlightenment’s original American champions. But Romantic notions of blood and soil would continue to have an unhealthy and corrupting effect on post-war American life, and an even deadlier legacy to visit upon the 20th-century world in the form of national and ideological despotisms. The perimeters of the Enlightenment, for all their faults, continue to protect human flourishing, and the energies and temperament of a Lincoln continue to be called forth in that flourishing’s defense.

Allen C. Guelzo serves at Princeton University as a Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities and Director of the Institute on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program.

ENDNOTES

[1] Herndon to Weik (November 12 and 21, December 16 and 28, 1885, January 1, 1886 & February 18, 1887), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, eds. Douglas L. Wilson & Rodney O. Davis ((Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 162, 171, 179, 238.

[2] Compare J.S. Mill “On the Probable Futurity of the Labouring Classes,” in Principles of Political

Economy, with some of their Application to Social Philosophy (London: John W. Parker, 1848), 2:322, with Lincoln, “Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin” (September 30, 1859), in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. R.P. Basler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 3:479. Likewise, compare Wayland, The Elements of Moral Science (Boston: Gould, Kendall & Lincoln, 1837), 193, with Lincoln’s “Fragment on Slavery” (1854) in CW 2:222. The connection to Wayland was first made by William Lee Miller in Lincoln’s Virtues: An Ethical Biography ((New York: Knopf, 2002), 277. Mill’s chapter was republished in the United States as early as 1849 in William H. Channing’s The Spirit of the Age.

[3] Robert B. Rutledge to Herndon (November 1866) in Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, eds. Douglas L. Wilson & Rodney O. Davis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 384; Herndon to Weik (December 16, 1885) and to Carpenter (December 19, 1866), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 57, 175.

[4] Borrett, Out West: A Series of Letters from Canada and the United States (London: Groombridge & Sons, 1866), 253-254.

[5] Hay, diary entry for July 25, 1863, in Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, eds. Michael Burlingame & J.R.T. Ettlinger (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 68; “To James H. Hackett” (August 17, 1863), in CW, 6:392.

[6] Henry Clay Whitney to Herndon (August 29, 1887), in HI, 636.

[7] Boorstin, The Americans: The National Experience (New York, 1965), 41, 430.

[8] Tocqueville, Democracy in America, eds. H. Mansfield and D. Winthrop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 404, 410, 428.

[9] Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Knopf, 1969), 2:317-332; Anthony Padgen, The Enlightenment And Why It Still Matters (New York: Random House, 2013)5-15, 22, 27, 78, 406-08; Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1992), 213, 216, 219; Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985), 60-66.

[10] “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (October 16, 1854) and “Speech in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania” (February 22, 1861), in CW, 2:266, 4:240. On the varieties of Enlightenment thinking within which Lincoln should be located, see Steven B. Smith, “Abraham Lincoln’s Kantian Republic,” in Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy, ed. Nicholas Buccola (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016), 216-237.

[11] Abner Y. Ellis to Herndon (January 30, 1866) and Herndon interview with John Todd Stuart (March 2, 1870), in HI, 179, 576; Lincoln, “Address Before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois” (January 27, 1838), “Temperance Address” (February 22, 1842), in CW, 1:115, 279; Lucas Morel, “Lincoln among the Reformers: Tempering the Temperance Movement,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 20 (Winter 1999), 2-3; Robert Bray, Reading With Lincoln (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010), 57-67.

[12] Herndon interview with Mary Todd Lincoln (September 1866), in HI, 359; Jason Emerson, Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), 9. On Lincoln’s Reading of Paine, see Richard Brookhiser, Founders’ Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln ((New York: Basic Books, 2014), 51-66.

[13] Herndon to John E. Remsburg (1880-1890), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 329.

[14] Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Human Understanding: And An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894), 81, 83-87; Herndon to Jesse Weik (February 25, 1887), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 243; “Handbill Replying to Charges of Infidelity” (July 31, 1846), in CW, 1: 382; Bray, Reading Lincoln, 50-52, 54-57, 140-146.

[15] “To James C. Conkling” (August 26, 1863), in CW, 6:406, 409; Michael Lind, What Lincoln Believed: The Values and Convictions of America’s Greatest President (New York: Doubleday, 2004), 59.

[16] Henry Belasyse, in Richard Grassby, The Business Community of Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 40; Peacham, The Compleat Gentleman: Fashioning Him absolute in the Most Necessary and Commendable Qualities (London, 1661),11-12; John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (London, 1720), 5:330.

[17] Boswell, Life of Johnson, ed. R.W. Chapman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 348, 597; Addison, “Spectator No. LXIX” (May 19, 1711), in The Spectator in Eight Volumes (Philadelphia: Tesson & Lee, 1803), 1:316.

[18] Lincoln, “Fragment on Free Labor” (September 17, 1859), in CW, 3:462; Lind, What Lincoln Believed, 92-100.

[19] “Richard Cobden,” Harper’s Weekly (May 13, 1865), 300-301; John Morley, The Life of Richard Cobden (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1881), 66, 536; “An English Republican,” New York Times (January 10, 1856)

[20] Lincoln, “First Debate with Stephen A. Douglas at Ottawa, Illinois” (August 21, 1858), in CW, 3:14.

[21] Edwards, Works of Jonathan Edwards: Religious Affections, ed. John E. Smith (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 100;

[22] Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 270; Thomas S. Kidd, The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 322.

[23] Wayland, “The Philosophy of Analogy”(1831), in American Philosophic Addresses, 1700-1900, ed. Joseph L. Blau (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946), 361.

[24] “Handbill Replying to Charges of Infidelity” (July 31, 1846), in CW, 1: 382.

[25] Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Reports of Lincoln’s Secretary, ed. Michael Burlingame (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 176; Browning to Isaac N. Arnold (November 25, 1872), in “Recollections of Lincoln: Three Letters of Intimate Friends,” Bulletin of the Abraham Lincoln Association 25 (December 1931), 9; Morton Borden, “The Christian Amendment,” Civil War History 25 (June 1979), 155–167; Lind, What Lincoln Believed, 48-53.

[26] Winckelmann, Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, trans. Henry Fuseli (London: A. Millar & T. Cadell, 1758), 30; The Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds (London: James Carpenter, 1842), 171, 183.

[27] Dickens, Hard Times, ed. D. Thorold (Ware: Wordsworth Classics, 1995), 4; Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern: World Society, 1815-1830 (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 187; Kenneth Clark, The Romantic Rebellion: Romantic Versus Classic Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 20; Burke, Philosophical Inquiry Into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (London: J. Dodsley, 1757), 95, 99, 110, 258.

[28] Herder, “Yet Another Philosophy of History for the Enlightenment of Mankind” (1774), in J.G. Herder on Social and Political Culture, ed. F.M. Barnard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 192; Heine, “Ludwig Boerne: A Memoir,” in Wit, Wisdom and Pathos, from the Prose of Heinrich Heine, trans. J. Snodgrass (London: Alexander Gardner, 1888), 215.

[29] Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1867), 114-115; Bray, Reading with Lincoln, 129; Brooks, “Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln,” in Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, ed. Michael Burlingame (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 219.

[30] J.J. Wright, in Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, eds. Don & Virginia Fehrenbacher (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 508; “Communication to the People of Sangamo County” (March 9, 1832) and “Fragment: Niagara Falls” (September 1848), in CW, 1:5, 2:10;; James Tackach, Lincoln and the Natural Environment (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2019), 12, 20.

[31] Herndon & Weik, Herndon’s Lincoln, eds. Douglas L. Wilson & Rodney O. Davis (Urbana: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 187-188.

[32] “Eulogy on Henry Clay” (July 6, 1852) and “Speech at Chicago, Illinois” (July 10, 1858), in CW, 2:122, 126, 499-500; Lind, What Lincoln Believed, 26; John Channing Briggs, Lincoln’s Speeches Reconsidered (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 116.

[33] Lord John Manners, England’s Trust, And Other Poems (London: J.G.F.& J. Rivington, 1841), 16; “Seventh and Last Debate with Stephen A. Douglas at Alton, Illinois” (October 15, 1858) and “Speech at New Haven, Connecticut” (March 5, 1860), in CW, 3:315, 4:24; John E. Roll, in RWAL, 383.

[34] “Mr. Calhoun’s Resolutions,” The United States Democratic Review 4 (November 1838), 132; Calhoun, “Speech on the Oregon Bill” (June 27, 1848), in Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun, ed. R.M. Lence (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1992), 566, 568-569; Harry V. Jaffa, A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 431.

[35] Bray, Reading Lincoln, 169; Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters (Richmond, VA: A. Morris, 1857), 79, 81, 86.

[36] Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or The Failure of Free Society (Richmond, VA: A. Morris, 1854), 21, 70, 72; (March 4, 1858), Hammond, “Kansas—Lecompton Constitution” (March 4, 1858), in Congressional Globe, 35th Congress, 1st session, 962

[37] Stephen V. Ash, Middle Tennessee Society Transformed, 1860-1870: War and Peace in the Upper South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 40.

[38] James L. Huston, The British Gentry, the Southern Planter and the Northern Family Farmer: Agriculture and Sectional Antagonism in North America (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015), 79, 83, 133, 158; The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge, for the Year 1859 (Boston: Crosby, Nichols, and Company, 1859), 214, 218.

[39] Forrest A. Nabors, From Oligarchy to Republicanism: The Great Task of Reconstruction (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2017), 247-49, 266; John Majewski, Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 81-82; Tourgée, A Fool’s Errand, by One of the Fools: The Famous Romance of American History (New York: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1880), 156; Stirling, Letters from the Slave States (London: John W. Parker, 1857), 63.

[40] “The Autobiography of John Esten Cooke,” ed. Hennig Cohen, American Literature 30 (May 1958), 236; “Progress of Federal Disorganization,” DeBow’s Review 24 (February 1858), 136; Russell, Pictures of Southern Life, Social, Political and Military (New York: James G. Gregory, 1861), 3, 4, 7.