Reconstruction: What Went Wrong?

By Hon. Frank J. Williams

Winning on the battlefield may be relatively “easy” compared to winning the peace afterward. Abraham Lincoln was a political genius in keeping together conservatives, moderates and Radicals during the American Civil War, especially after he found generals who could win battles. But things change and the longer that time passes, the more likely it is that presidents lose their influence. Most presidents find that the window for opportunity is limited to “the first-hundred days” phenomenon. Assassinations cut short plans and people tire of a policy that does not lead to a quick end.

Lincoln understood how to win a major civil war as a political revolution but implementing his “new birth of freedom” was a gigantic peacetime project involving a social revolution. If a bullet had not killed him, even his expectations might have been diminished in achieving Reconstruction.

This article focuses primarily on: (1) Andrew Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction which was nearly opposite to what Lincoln had wanted; and (2) Ulysses S. Grant’s approach which was more like Lincoln’s approach and produced some short-term positive results, but the nation’s focus changed. Johnson barely survived impeachment, while Grant’s policy was ended in the Bargain of 1877 – a national cop out.

In personality and outlook, President Andrew Johnson was ill suited for the responsibilities he now shouldered following Lincoln’s assassination. A lonely, stubborn man, he was intolerant of criticism and unable to compromise. He lacked Lincoln’s political skills and keen sense of Northern public opinion. Although Johnson had supported emancipation during the war, he held deeply racist views. A self-proclaimed spokesman for poor white farmers of the South, he condemned the old planter aristocracy, but believed African-Americans had no role to play in Reconstruction. Thus, Johnson proved incapable of providing the nation with enlightened leadership.

With Congress out of session until December, Johnson in May 1865 outlined his plan for reuniting the nation. He issued a series of proclamations and more amnesties than any president in American history. But rather than magnanimous acts, Johnson offered a pardon to all Southern whites, except Confederate leaders and wealthy planters (and most of these subsequently received individual pardons), who took an oath of allegiance. He also appointed provisional governors and ordered state conventions – elected by whites alone. Apart from the requirement that they abolish slavery, repudiate secession, and abrogate the Confederate debt, the new governments were granted a free hand in managing their affairs. Previously, Johnson had spoken of severely punishing “traitors,” and most white Southerners believed his proposals surprisingly lenient.

Radical Republicans criticized Johnson’s plan of Reconstruction for ignoring the rights of the former slaves. But at the outset, most Northerners believed the policy deserved a chance to succeed. The conduct of the new Southern governments elected under Johnson’s program, however, turned most of the Republican North against the president.

Johnson assumed that when elections were held for governors, legislators, and congressmen, Unionist yeoman would replace the planters who had led the South into secession. In fact, white voters by and large returned the old elite to power. Republicans and black leaders like Frederick Douglass were further outraged by reports of violence directed against former slaves and Northern visitors in the South. But what aroused the most opposition were laws passed by the new Southern governments, the Black Codes, which granted freed people limited rights, such as the right to own property and bring suit in court. But African-Americans could not testify against whites, serve on juries or in state militias, or vote. The Black Codes required blacks to sign yearly labor contracts and unemployed vagrants were subject to arrest, fines, and being hired out to white landowners. Some states limited occupations open to blacks and prevented them from acquiring land. The Black Codes, wrote one Republican, were attempts to “restore all of slavery but its name.”

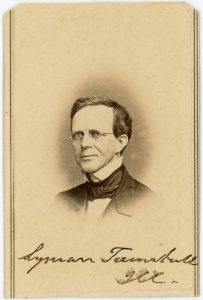

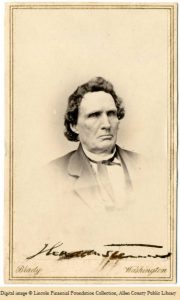

After Congress assembled in December 1865, Johnson announced that with loyal governments functioning in all the Southern states, Reconstruction was over. This led moderates to join Radicals, like Thaddeus Stevens, in refusing to seat Southerners recently elected to Congress. Then they established a Joint Committee to investigate the progress of Reconstruction. Early in 1866, Lyman Trumbull, a senator from Illinois, proposed two bills, reflecting the moderates’ belief that Johnson’s policy required modification. The first extended the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been established for only one year. The second, the Civil Rights Bill, was described by one congressman as “one of the most important bills ever presented to the House for its action.” The bill left the new Southern governments in place, but required them to accord blacks the same civil rights as whites. It made no mention of the right to vote.

Passed by overwhelming majorities in both the Houses of Congress, the Civil Rights Bill represented the first attempt to define in legislative terms the essence of freedom and the rights of American citizenship. In empowering the federal government to guarantee the principle of equality before the law, regardless of race, against violations by the states, it embodied a profound change in federal-state relations. To the surprise of Congress, Johnson vetoed both bills. Johnson offered no possibility of compromising with Congress; he insisted instead that his own Reconstruction program be left unchanged. The vetoes made a complete breach between Congress and the president inevitable. In April 1866, the Civil Rights Bill became the first major law in American history passed over a presidential veto. That law is still used today. Ironically, it has been used by opponents of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) as the 1866 act includes all rights of the ERA.

Unfortunately, there was no override of Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Act. But a look at the Freedmen’s Bureau Act is instructive on its successes. Freedmen’s Bureau schools quickly achieved “spectacular gains in literacy.” Less than two months after the end of the war, Freedmen’s schools were educating 2,000 children in Richmond, VA. By spring of 1866, at least 975 schools were educating more than 90,000 students in 15 Southern states. By late 1869, more than 250,000 pupils were enrolled in Freedmen’s schools. Literacy was imperative for black economic security. Ex-slaves needed to read in order to understand deeds and labor contracts. Indeed, this was exactly the cornerstone of Lincoln’s and Grant’s hope and plan for African-Americans to understand and enjoy the civil rights that should come from freedom and citizenship.

Although Freedmen’s schools were open to whites, few attended. “Despite the absence of statewide systems in most Southern states, most parents preferred to consign their children to illiteracy rather than to see them educated alongside black children.” White families who did send their children to bureau schools were typically ostracized or physically beaten.

In the postwar years, blacks in the North, inspired by the new civil-rights legislation and the heroic example set by black Union troops during the war, were more willing to confront authority and challenge the North’s own ingrained racism. Northern blacks, though not subject to the same violence as in the South, were sometimes denied equal schooling, segregated in public conveyances and abused when they tried to vote.

Although defenders of the old South will doubtlessly disagree, there is a compelling case that American society as a whole would have benefited mightily had Reconstruction been permitted to fulfill its early promise. In particular, it would have saved the U.S. from the long Jim Crow agony of racial repression and the distortion of national politics by the South’s determination to protect segregation at any price. So what went wrong?

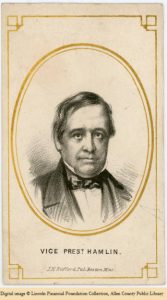

Reconstruction’s problems began with what was arguably the worst decision that Abraham Lincoln made as president, when he dropped from his 1864 re-election ticket his capable vice president, the abolitionist Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, and replaced him with Andrew Johnson, the Unionist Democrat from Tennessee. There is still a question of Lincoln’s role in this switch. But I see his fine Machiavellian hand here. There is no way Andrew Johnson could become the vice presidential nominee of the National Union Party without the president’s acquiescence. Fearing defeat in the November election, Lincoln hoped to shore up support among Northern Democrats and win the trust of voters in the re-conquered areas of the seceded states.

Lincoln’s assassination, a week after Appomattox, put Reconstruction in the hands of a racist, formerly slave-owning alcoholic who sabotaged efforts to extend civil rights – and physical protection – to newly freed slaves. Johnson encouraged Southern whites to re-assert their power and ignored violence against Freedmen and white Unionists who were trying to form biracial coalitions. By executive order, he returned hundreds of thousands of acres to white planters. Republican military officers were replaced with compliant Democrats, many of whom averted their gaze when armed “white leagues” drove teachers from their schools, assassinated local black leaders, and intimidated defenseless black and white Unionist voters. Blacks who dared to defend themselves were murdered whole-sale. Lawlessness, not Reconstruction, became the order of the day.

In June 1866, Congress approved the Fourteenth Amendment, which broadened the federal government’s power to protect the rights of all Americans. It forbade states from abridging the “privileges and immunities” of American citizens or depriving any citizen of the “equal protection of the laws.” In a compromise between Radical and moderate positions on black suffrage, it did not give blacks the right to vote, but threatened to reduce the South’s representation in Congress if black men continued to be denied the ballot. The amendment also barred repayment of the Confederate debt and prohibited many Confederate leaders from holding state and national office. And it empowered Congress to take further steps to enforce the amendment’s provisions.

The most important change in the Constitution since the adoption of the Bill of Rights, the Fourteenth Amendment established equality before the law as a fundamental right of American citizens. Until the Supreme Court constricted the Fourteenth Amendment, it shifted the balance of power within the nation by making the federal government, not the states, the ultimate protector of citizens’ rights – a sharp departure from pre-war traditions, which viewed centralized power, not local authority, as the basic threat to Americans’ liberties. In authorizing future Congresses to define the meaning of equal rights, it made equality before the law a dynamic, elastic principle. The Fourteenth Amendment and Congressional policy of guaranteeing the civil rights for blacks became the central issues of the political campaign of 1866. Congress now demanded, that in order to regain their seats in the House and Senate, the Southern states must ratify the amendment. Johnson denounced the proposal and embarked on a speaking tour of the North, the “swing around the circle.” Denouncing his critics, the president made wild accusations that the Radicals were plotting to assassinate him. His behavior further undermined public support for his policies, just as his drunken behavior had done at his inauguration as Vice President.

In the Northern congressional elections that fall, Republicans won a sweeping victory. Nonetheless, egged on by Johnson, every Southern state but Tennessee refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. The intransigence of Johnson and the bulk of the white South further pushed moderate Republicans toward the Radicals. In March 1867, over Johnson’s veto, Congress adopted the Reconstruction Act, which divided the South into five military districts, temporarily barred many Confederates from voting or holding office, and called for creation of new governments in the South, with black men given the right to vote. Only after the new governments ratified the Fourteenth Amendment could the Southern states finally be re-admitted to the Union. Thus began the period of Congressional or Radical Reconstruction, which lasted until the fall of the last Southern Republican government in 1877. It was the nation’s first real experiment in interracial democracy.

In order to shield its policy against presidential interference, Congress in March 1867 adopted the Tenure of Office Act, which may have been unconstitutional as a violation of separation of powers, barring the president from removing certain officeholders, including Cabinet members, without the consent of the Senate. In February 1868, Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, an ally of the Radicals. The House of Representatives responded by approving articles of impeachment against the president. Virtually all Republicans, by this point, considered Johnson a failure as president and an obstacle to a lasting Reconstruction, but some moderates disliked the prospect of elevating to the presidency Benjamin Wade, a Radical who, as president pro tem of the senate, would succeed Johnson. Wade in some ways was a mirror image of Johnson in terms of personality. The final tally to convict Johnson was one vote short of the two-thirds necessary to remove him from office. Seven Republicans had joined Democrats in voting to acquit the president.

Johnson’s acquittal weakened the Radicals’ position and made the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant as the party’s presidential candidate inevitable. The nation’s greatest war hero initially had supported Johnson’s policies. Eventually, Grant came to side with Congress, but Radicals worried that he lacked strong ideological convictions. His Democratic opponent Horatio Seymour was the colorless former New York governor. Reconstruction was the central issue of the 1868 campaign. The campaign was bitter. Republicans identified their opponents with secession and treason, a tactic known as “waving the bloody shirt.” Democrats appealed openly to racism, charging that Reconstruction would lead to interracial marriage and black supremacy throughout the nation.

Grant won the election, although by a margin many Republicans found uncomfortably close. He received overwhelming support from black voters in the South, but Seymour may well have carried a majority of the nation’s white vote. Nonetheless, the result was a vindication of Republican reconstruction and inspired Congress to adopt the era’s third amendment to the Constitution. In February 1869, Congress approved the Fifteenth Amendment, prohibiting the federal and state governments from depriving any citizen of the right to vote because of race, except women. Bitterly opposed by the Democratic Party, it became part of the Constitution in 1870.

In 1868, even after Congress had enfranchised black men in the South, only Northern states had allowed black men to vote. In March 1870, the American Anti-Slavery Society disbanded, its work, its members believed, now complete. Congressional Reconstruction policy was now essentially complete. Henceforth, the focus was on Reconstruction within the South. Among the former slaves, the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which brought black suffrage to the south, caused an outburst of political organization.

Throughout Reconstruction, black voters provided the bulk of the Republican Party’s support. Although Democrats charged that “Negro rule” had come to the South, nowhere did blacks control the workings of state government, and nowhere did they hold office in numbers equal to their proportion of the total population (which ranged from about 60 percent in South Carolina to around one-third in Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas). Nonetheless, the fact that well over 1,500 African-Americans occupied positions of political power in the Reconstruction South represented a stunning departure in American government. The new Southern Republican party also brought to power whites who had enjoyed little authority before the Civil War.

Given the fact that many of the Reconstruction governors and legislators lacked governmental experience, their record is remarkable. The new governments established the South’s first state-supported public school systems, as well as numerous hospitals and asylums for orphans and the insane. These institutions were open to blacks and whites, although generally, they were segregated. Only in New Orleans were public schools integrated during Reconstruction, and only in South Carolina did the state university admit black students (elsewhere separate colleges were established for blacks).

In assuming public responsibility for education, Reconstruction governments followed a path blazed by the North. Their efforts to guarantee African-Americans equal treatment in transportation and places of public accommodation, however, launched these governments into an unknown area in American law. Racial segregation, or the complete exclusion of blacks from both public and private facilities, was widespread throughout the country. Black demands for the outlawing of such discrimination produced deep divisions in the Republican Party. But in the Deep South, where blacks made up the vast majority of the Republican voting population, laws were enacted making it illegal for railroads, hotels, and other institutions to discriminate on the basis of race. Enforcement of these laws varied considerably, but Reconstruction established for the first time at the state level, a standard of equal citizenship and recognition of blacks’ right to public services.

Republican governments also took steps to assist the poor of both races and to promote the South’s economic recovery. The Black Codes were repealed, the property of small farmers protected against being seized for debt, and the tax system revised to shift the burden from propertyless blacks, who had paid a disproportionate share during Presidential Reconstruction, to planters and other landowners. The former slaves, however, were disappointed that little was done to assist them in acquiring land. Only South Carolina took effective action, establishing a commission to purchase land for resale on long-term credit to poor families.

Rather than land distribution, the Reconstruction governments pinned their hopes for Southern economic growth and opportunity for African-Americans on a program of regional economic development. Railroad construction was its centerpiece, the key, they believed to linking the South with Northern markets, and transforming the region into a society of booming factories, bustling towns, and diversified agriculture. The program had mixed results. A few states-Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, and Texas-witnessed significant new railroad construction between 1868 and 1872, but economic development in general remained weak. With abundant opportunities existing in the West, few Northern investors ventured to the Reconstruction South.

Thus, to their supporters, the government of Radical Reconstruction presented a complex pattern of achievement and disappointment. The economic vision of a modernizing, revitalized, Southern economy failed to materialize, and most African-Americans remained locked in poverty. On the other hand, biracial democratic government, a thing unknown in American history, for the first time functioned effectively in many parts of the South. Public facilities were rebuilt and expanded, school systems established, and legal codes purged of racism. The conservative oligarchy that had dominated Sothern government from colonial times to 1867 found itself largely excluded from political power, while those who had previously been outsiders – poorer white Southerners, men from the North, and especially former slaves – cast ballots, sat on juries, and enacted and administered laws. The effect upon African-Americans was strikingly visible.

The South’s traditional leaders – planters, merchants, and Democratic politicians – bitterly opposed the new Southern governments, denouncing them as corrupt, inefficient, and embodiments of wartime defeat and “black supremacy.” There was corruption during Reconstruction, but it was confined to no race, region, or party.

The most basic reason for opposition to Reconstruction, however, was that most white Southerners could not accept the idea of former slaves voting, holding office, and enjoying equality before the law. They had always regarded blacks as an inferior race whose proper place was as dependent laborers. They believed that Reconstruction had to be overthrown in order to restore white supremacy in Southern government, and to ensure that planters would have a disciplined, reliable labor force.

The violence that greeted the advent of Republican governments after 1867 was pervasive, organized, and explicitly motivated by politics. In wide areas of the South, Reconstruction’s opponents resorted to terror to secure their aim of restoring Democratic rule and white supremacy. Secret societies sprang up whose purpose was to prevent blacks from voting, and to destroy the infrastructure of the Republican Party by assassinating local leaders and public officials.

The most notorious of such organizations was the Ku Klux Klan, which in effect served as a military arm of the Democratic Party. Founded as a Tennessee social club, the Klan was soon transformed into an organization of terrorist criminals, which spread into nearly every Southern state. Led by planters, merchants, and Democratic politicians, men who liked to style themselves the South’s “respectable citizens” and “natural rulers,” the Klan committed some of the most brutal acts of violence in American history. Grant’s election did not end the Klan’s activities; indeed in some parts of the South, Klan violence accelerated in 1869 and 1870. The Klan singled out for assault Reconstruction’s local leadership. White Republicans – local officeholders, teachers, and party organizers – were often victimized. In 1870 William Luke, an Irish-born teacher in a black school, was lynched in Alabama along with four black men. Both female and male teachers were beaten.

Although some Northern Republicans opposed further intervention in the South, most agreed with Senator John Sherman of Ohio, who affirmed that the “power of the nation” must “crush, as we once before have done, this organized civil war.” In 1870 and 1871, Congress adopted three Enforcement Acts, outlawing terrorist societies and allowing the president to use the army against them. These laws continued the expansion of national authority during Reconstruction by defining certain crimes – those aimed at depriving citizens of their civil and political rights – as federal offenses rather than merely violations of state law. In 1871, President Grant authorized federal marshals under the new Department of Justice, backed up by troops in some areas, to arrest hundreds of accused Klansmen and bring them to trial.

Despite the Grant administration’s effective response to Klan terrorism, the North’s commitment to Reconstruction waned during the 1870s. Many radical leaders, including Thaddeus Stevens, who died in 1868, had passed from the scene. Within the Republican Party, their place was taken by politicians less committed to the ideal of equal rights for blacks. Many Northerners felt that the South should be able to solve its own problems without constant interference from Washington. The federal government had freed the slaves, made them citizens, given them the right to vote, and crushed the Ku Klux Klan. Now, blacks should rely on their own resources, not demand further assistance from the North.

Other factors also weakened Northern support for Reconstruction. In 1873, the country plunged into a severe economic depression. Distracted by the nation’s economic problem, Republicans were in no mood to devote further attention to the South. Congress did enact one final piece of civil rights legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed racial discrimination in places of public accommodation. This was a tribute to Senator Charles Sumner, who died in 1874 after devoting his career to promoting the principles of equality before the law.

In those states where Reconstruction survived, violence again reared its head, and this time, the Grant administration showed no desire to intervene, in part because of lack of public support. In contrast to the Klan’s activities – conducted at night by disguised men – the violence of 1875 and 1876 took place in broad daylight, as if to flaunt Democrats’ conviction that they had nothing to fear from Washington.

In January 1877, unable to resolve the crisis of the election of 1866, Congress appointed a fifteen-member Electoral Commission, composed of senators, representatives, and Supreme Court justices. Republicans enjoyed an 8 to 7 majority on the Commission, and to no one’s surprise, the members decided that Rutherford B. Hayes had carried the disputed Southern states and was elected. The Bargain of 1877 recognized Democratic control of the remaining Southern states, and Democrats would not block the certification of Hayes’s election by Congress. He became president, ended federal intervention in the South, and ordered United States troops, who had been guarding the state houses in South Carolina and Louisiana, to return to their barracks (not to leave the region entirely, as is widely believed). The redeemers, as the Southern Democrats who overturned Republican rule called themselves, now ruled the entire South. Reconstruction had come to an end.

One might say that the violence that had crushed Reconstruction’s highest aspirations now reaped its reward: Northern abdication and Jim Crow.

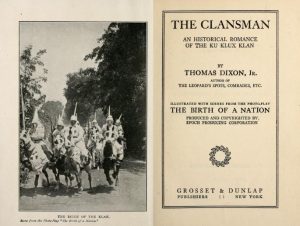

A particularly glaring deficit in our memory, that black officeholders in the early Reconstruction era – demeaned by many pro-Southern historians and portrayed as lascivious buffoons by fictionalizers such as Thomas Dixon, Jr., whose novel became the basis for “Birth of a Nation” – were actually substantial citizens who were well prepared to govern. These blacks had often risen from a middle class of ministers and businessmen that existed in antebellum America beyond the view of racist whites. By the turn of the 20th Century however, once-effective biracial coalitions across the South had been destroyed and black voters almost completely disenfranchised through physical intimidation and electoral trickery, White supremacists took control in the former Confederate states. And our Supreme Court did not help either. For, by this time, we had a policy of “separate but equal” as espoused in the 1895 decision – Plessy v. Ferguson. It would take 60 years to correct this inequity with Brown v. Board of Education.

Anyone who lived or worked in the Jim Crow South could see the price that African-Americans paid for the crippling of Reconstruction. In the mid-1960s, it was always difficult to persuade would-be voters to appear before hostile white registrars, even more so after the Ku Klux Klan held a rally festooned with Confederate flags on the steps of the courthouse where the blacks were required to register.

A century after the Civil War, blacks in the South could still feel so vulnerable that they would flee at the sight of a white stranger. Members of a nation who rightly regard themselves as residents of a more just and democratic society than many others on the planet are collectively loath to admit that good and honorable policies were consciously overturned by a reactionary minority while thousands of people across the nation found it easier to look the other way.

Perhaps Abraham Lincoln was naïve about his hope to reconstruct the South. He had thought the Civil War would be a short one and, after that turned into a false hope, most of his time was spent on how to win a long one. The transition from a slave to a free society would take a social revolution. The Johnson administration seems to confirm the Founders wisdom about character and the danger of demagogues.

Ulysses S. Grant’s administration confirms Lincoln’s remark that Americans are “the almost chosen people.” Grant was running a race against time – not only in regard to white southerners who had been displaced from power, but also the flashflood of his cronies whom he had trusted. Yet, Grant did yeoman service to Lincoln’s dream in suggesting that justice in an open society would eventually become more likely in the long term.

One might even take the view of the historian Barbara Fields, who eloquently said in Ken Burns’s Civil War documentary that if, as she believes, the Civil War was a “Struggle to make something higher and better out of the country,” then “the Civil War is now over.”

[Portions of this article were presented by Hon. Frank J. Williams as a lecture at Mississippi State University, the site of the Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana.]