Politics and Lincoln’s Relationship with Indiana

Indiana’s influence on Abraham Lincoln has long divided historians. What separates them, according to Mark E. Neely, Jr., are two opposing interpretations: the “dunghill” and “chin fly” theses. Proponents of the dunghill thesis say that Indiana was primitive and backward, a dunghill, which Lincoln surmounted because of his native talents. Chin fly adherents admit the Indiana frontier was primitive, but argue it offered the delights of rural life and strengthened the growing youth physically and mentally. In Neely’s view, the dunghill thesis is better supported by Lincoln’s recollections of his Indiana childhood.

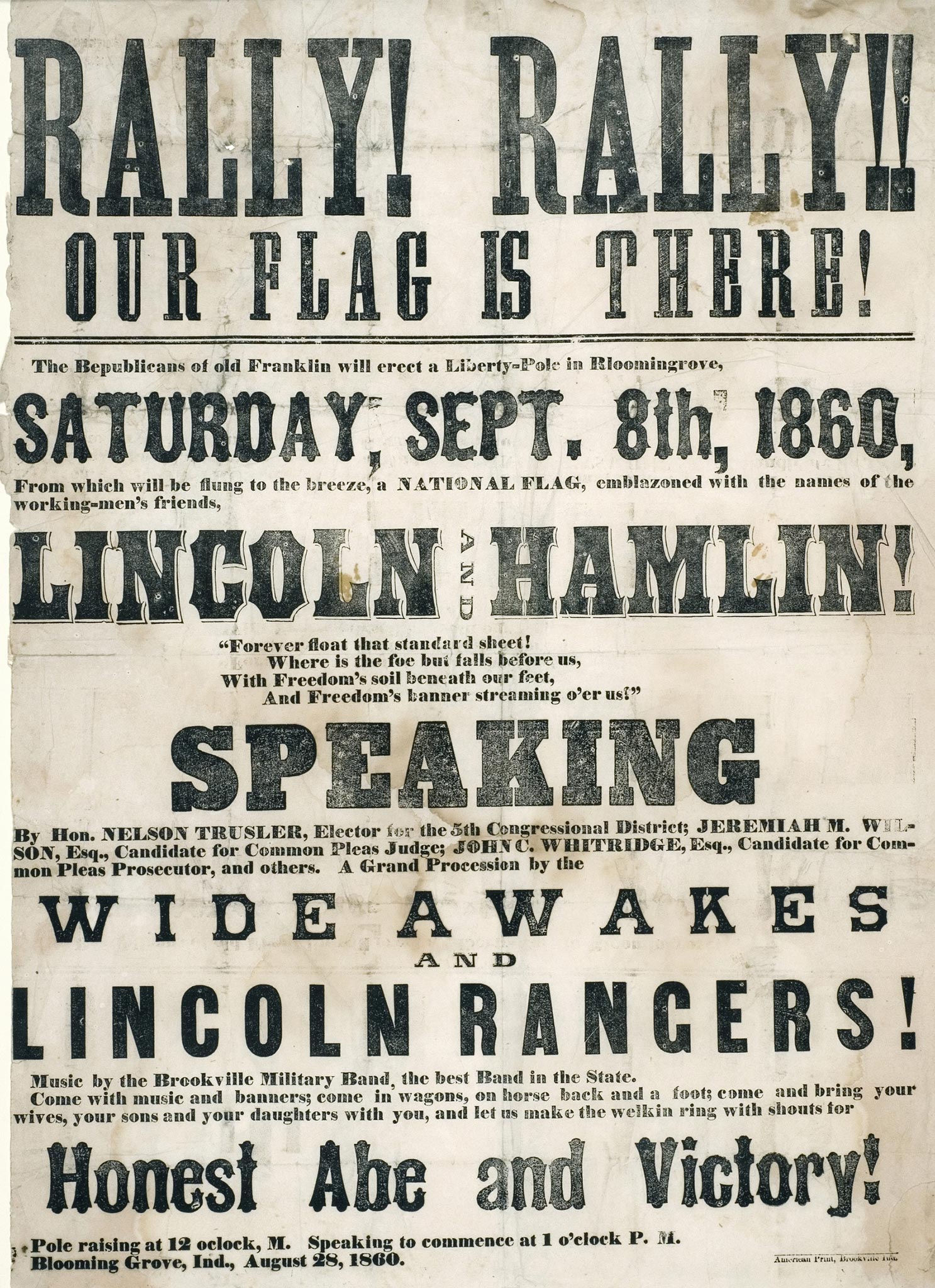

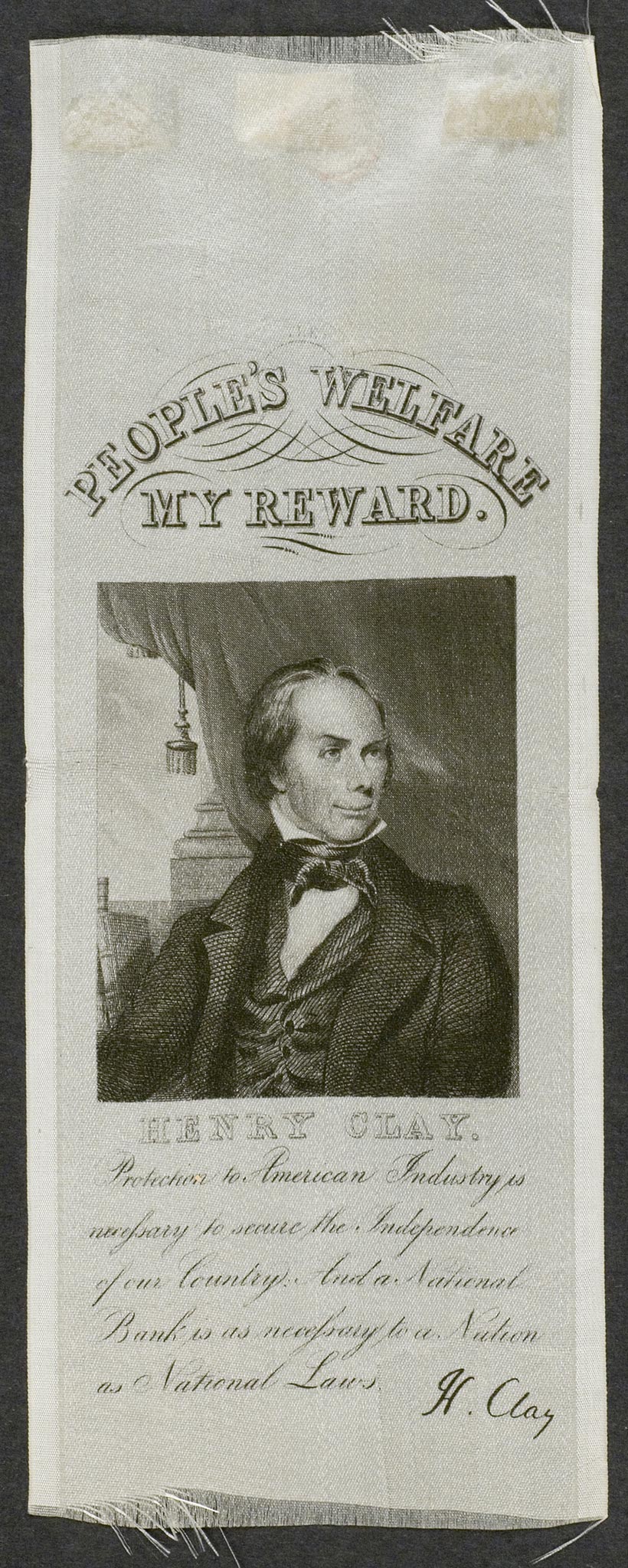

Moreover, Lincoln’s Indiana youth even explains his political loyalties. Why become a Whig in a predominantly Democratic state, as were both Indiana and Illinois? Lincoln’s law partner, William Herndon, said that Lincoln’s ambition was “a little engine that knew no rest.” But Lincoln’s ambitions did not triumph over his principles. Had he been willing to become a Democrat, like most of his family, he might have had more political experience than just one term in Congress by the time he became a national political figure. Lincoln was a Whig, Neely contends, because the Whigs “offered a program to change the West, to improve the defects of the environment of Lincoln’s youth.”

The Whig platform, which was embodied in the American System of Lincoln’s political idol, Henry Clay, included a protective tariff for manufactures, a national bank, and government funding for internal improvements.

But Lincoln was never a strong voice on the tariff issue, which tended to pit manufacturing parts of Illinois and Indiana against the agricultural southern parts of those states. As a presidential candidate, he advocated a protective tariff to win the electoral votes of Pennsylvania. His position that it was wasteful to import what could be produced at home was a long-standing nationalist argument for tariffs. Once elected, he deferred to Congress’s judgment on the protectionist Morrill Tariff.

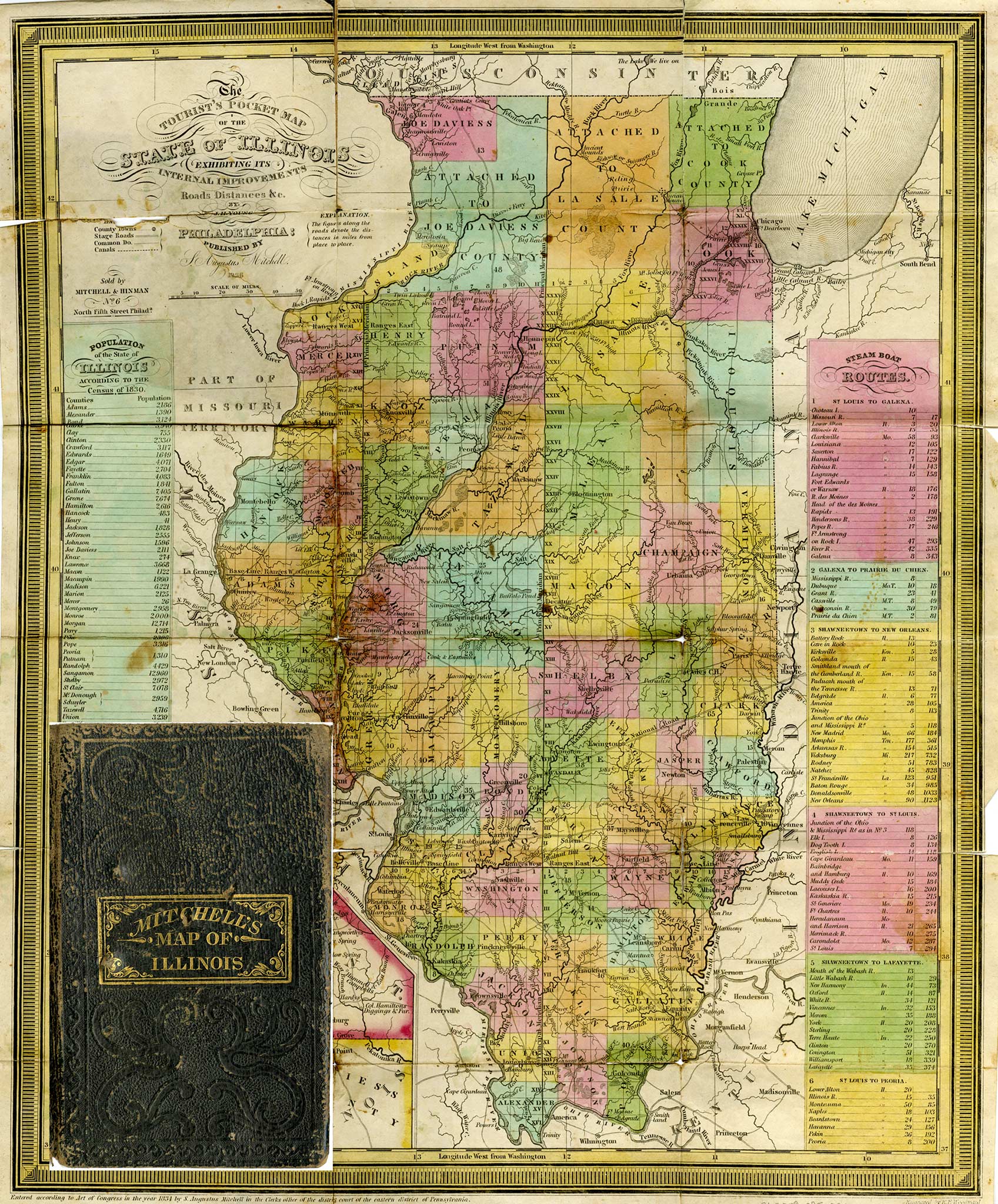

Lincoln fought much harder for a state bank in Illinois. Such a bank would be useful to finance internal improvements and stimulate the economy, as was the case in Indiana, where many Hoosiers supported banks as providing the capital necessary for manufacturing, agriculture, and commerce to flourish. As long as banks did not become “moneyed aristocracies” that aided the wealthy to enrich themselves at the poor’s expense, banks could promote economic opportunity. An Illinois man accused the state bank of favoritism, claiming that it waived interest payments for favored debtors. At the same time, Lincoln got himself appointed to the legislative committee investigating the bank so that he could protect the state bank from Democratic attacks. It was to prevent a vote forcing the bank to resume specie payments, which would have bankrupted the institution, that Lincoln and fellow Whigs jumped out the statehouse window to break a quorum. During the depression of the late 1830s, specie payments were suspended by the Indiana state bank, which also was accused of favoritism in its loan-making and also survived an investigation of its practices. But the Indiana bank had bipartisan support and did not face the life-or-death struggle of the Illinois bank.

Banks were tools to finance internal improvements, an issue particularly dear to Lincoln’s heart. As Neely puts it, “If [Lincoln] ever stared moodily at the Sangamon River, as modern motion pictures sometimes portray him, he was probably thinking of turning it into a barge canal.” In 1837, Lincoln led the state legislature in passing a large internal improvements bill. Illinois allocated $10 million for canals, roads, and railroads.

A year earlier, Indiana had already passed its own Mammoth Internal Improvements Bill, also for $10 million. Both states incurred large debts when the economy crashed after the Panic of 1837 and were left with unfinished, unprofitable improvements.

Lincoln’s politics finally moved him from the minority into the majority when slavery expansion became the dominant political issue. In the 1850s, Northerners struggled to keep the “Slave Power” from dominating the territories. Even so, Indiana and Illinois were both black law states, meaning they had legal prohibitions against African Americans testifying against whites, marrying whites, voting, serving in the militia, and migrating into the state. Lincoln professed to share Midwestern prejudices against political and social equality between the races. He supported colonization—the program of resettling African Americans in an African colony. (Colonization was Indiana’s official policy for dealing with that state’s black population.) But he clearly condemned slavery as immoral and in contradiction with the Declaration of Independence. His opponents seized on this to label him a “Black Republican” who favored black equality and abolition. Certainly white Southerners agreed that Lincoln and the Republicans were a sufficient threat to slavery and white supremacy to justify secession.

Lincoln’s roots in black law states probably enabled him to understand that Northerners needed to be guided towards accepting expanded black rights. He insisted that emancipation was a military necessity and issued the Emancipation Proclamation in accordance with his authority as commander in chief. And by the end of his life, Lincoln was advocating black suffrage for some black men, the educated and soldiers. He died before it could be seen whether he would go as far as more radical Republicans who advocated—and eventually got—universal male suffrage, regardless of race; black citizenship; and constitutional provisions for equal rights.

Democrats feared, correctly, that expanded black rights would overturn Midwestern black laws. But many Midwesterners had accepted that slavery, as the cause of the war, had to be ended and that blacks, as a loyal southern population, had to be empowered in order to end the reign of the Slave Power.

Indiana, in perhaps ironic ways, promoted Lincoln’s success. The Hoosier state gave the young politician a model to reject, and thereby helped form his political policies. And it was in Indiana that Lincoln gained a deep understanding of racism, which allowed him to gently push the North towards making the promises of the Declaration of Independence real for all Americans, regardless of race.

Sources: Donald F. Carmony, Indiana, 1816-1850: The Pioneer Era (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1998; David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995); Nicole Etcheson, The Emerging Midwest: Upland Southerners and the Political Culture of the Old Northwest, 1787-1861 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996); Mark E. Neely, Jr., Escape from the Frontier: Lincoln’s Peculiar Relationship with Indiana (Fort Wayne: Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, n.d.).

Nicole Etcheson is the Alexander M. Bracken Professor of History at Ball State University. This material was presented at the Lincoln Symposium at the Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, Indiana, in November 2016.