Placing the Platform: Using 3D Technology to Pinpoint Lincoln at Gettysburg

Placing the Platform: Using 3D Technology to Pinpoint Lincoln at Gettysburg

By Christopher Oakley

The following presentation was delivered at The Lincoln Forum in Gettysburg on November 18, 2022. It has been slightly revised for clarity.

One hundred fifty-nine years ago, on November 18, 1863, Abraham Lincoln came here, to Gettysburg. The purpose of his trip was to preside as the chief executive over the consecration ceremony for our country’s first national cemetery.

To those with even a casual interest in Lincoln, the facts of the story are familiar. We know that a prominent local attorney named David Wills invited Lincoln to make “a few appropriate remarks” at the dedication of what is now the Gettysburg National Cemetery. We know that Lincoln finished writing his speech while he was in Gettysburg. We know that on the morning of the 19th, Lincoln mounted a chestnut horse and rode in a grand parade from downtown Gettysburg to the new and uncompleted Soldiers’ National Cemetery. We know that an estimated crowd of 15,000 spectators showed up to witness the ceremony. We know the main orator of the day, Edward Everett, spoke for two hours and that Lincoln spoke for a little over two minutes. We know all of this because it was widely reported by the press and has been written about in history books ever since. But for all the hoopla over Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and all the witnesses to it, there is one thing we don’t know—where Lincoln was actually standing when he called for a national “new birth of freedom.”

Over the years, several scholars and bloggers have attempted to identify the location where the Gettysburg Address was delivered. These researchers relied on written and photographic records from the 19th century to reach their conclusions. But each of those locations, some more accurate than others, must be classified as “educated guesses” since there were no scientific methods available to test them.

I have been asked to share with you some of my research into where Lincoln stood when he delivered his Gettysburg Address. I have also been asked to show you how my undergraduate students and I married 19th-century analog materials with 21st-century 3D digital technology to solve this lingering mystery. Over the past ten years our deep dive into the digital humanities has led me to understand that some of what we’ve been told about Lincoln at Gettysburg is, frankly, suspect. My goal is to offer a new perspective. As revealed by 3D digital modeling, a lot of old-fashioned photographic sleuthing, and a healthy dose of common sense, I can tell you exactly where Lincoln stood to deliver the most famous speech in American history.

I’m a former Disney animator and currently a professor in New Media. People often ask me, “What the heck in New Media?” I’ll give you a very technical definition—we make cool stuff on computers. And this is precisely what led me to this area of research. That, and my fixation on all things Abraham Lincoln. I share that passion for Lincoln with Walt Disney. When Walt Disney was a young schoolboy, he memorized the Gettysburg Address and delivered it to his classroom. The school’s principal was so impressed, he asked Walt to go to every classroom in the school and deliver the speech. Walt’s obsession with Lincoln lasted throughout his lifetime. It reached a climax when he and his Imagineers brought Lincoln back to life through Audio-Animatronics for the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Using cutting-edge robotics, “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” still delights Disneyland audiences to this day.

Back in 2011, in the spirit of Walt Disney, I launched an undergraduate research endeavor called “The Virtual Lincoln Project.” The initial concept was to have my animation students create a digital, photo-real Abraham Lincoln, and bring him to life delivering his Gettysburg Address. We digitally scanned two life masks of Lincoln to get our project underway. We took those scans into a program called Maya, which is an industry-standard software used for animation, digital modeling, and creating special effects for film and television. Several teams of students labored on this project over many years. Unfortunately, the project was put on hold when the pandemic hit.

Early in our production, however, we began building the 3D digital environment that would be needed for our recreation of Lincoln’s speech. In 2013, I brought nine of those students here to Gettysburg. The purpose of the trip was to make this place real for the students and not just a series of zeros and ones in a computer program. While in Gettysburg, we took hundreds of reference photos and videos. We even measured the iconic Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse with lasers. Because the gatehouse was a front row witness to the Battle of Gettysburg and to Lincoln’s address, we knew a digital model of it would be needed for our digital world. Using the measurements taken on site, as well as 19th-century photographs of the gatehouse we had found online in the Library of Congress’ Prints and Photographs Division, my students created a highly accurate 3D digital model of the structure.

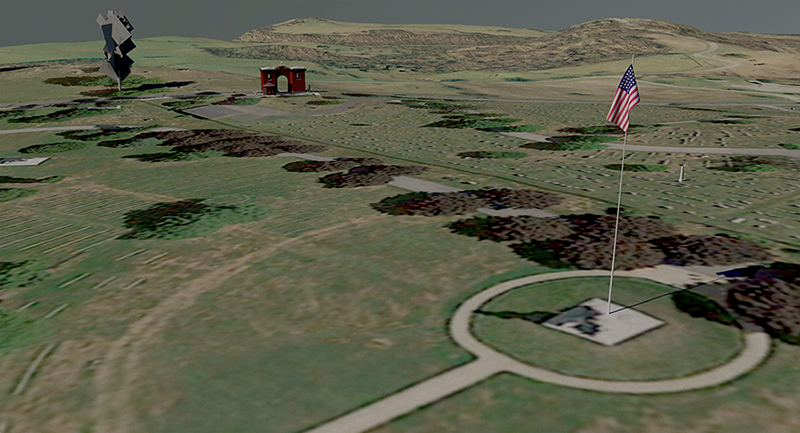

When we got back to North Carolina, I downloaded geographic data from the Internet for both Evergreen Cemetery and the National Cemetery and gave this data to UNC Asheville’s Atmospheric Science department. A few days later, they gave me a three-dimensional GIS map. I took that map into our Maya modeling software and was completely blown away by its accuracy. Every hill, valley, stream, and road was clearly visible. To this surface we added a Google satellite map—and it all lined up perfectly. This would serve as the foundation for our digital world.

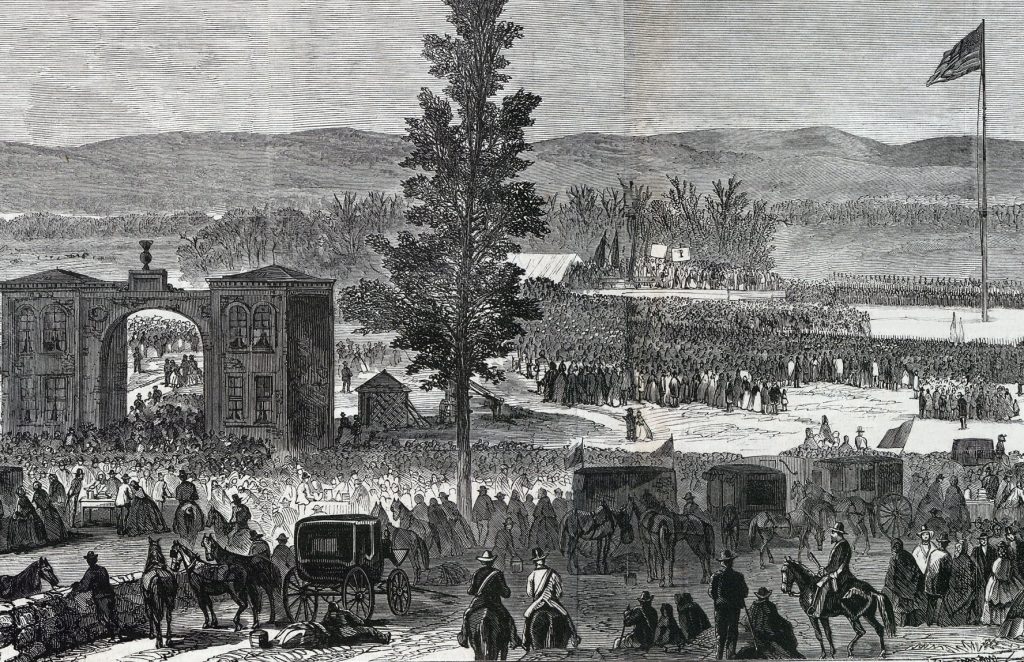

To build upon that foundation, we added the two objects whose locations are absolutely known—the gatehouse and a flagpole that had been erected for the consecration ceremony where the Soldiers’ National Monument now stands. Finally, we added a 90-foot poplar tree that in 1863 stood across the street from the gatehouse. [Fig. 1]

But what was missing in our 3D world was the speaker’s stand where Lincoln delivered the address. Historical accuracy was our goal, so I told the students to keep working on everything else while I figured out what the platform looked like and where it was located. I had no idea what I was getting into!

I began by using the same 19th-century materials that other researchers have used—the written record, illustrations, maps, and a handful of photographs. Recent scholarship of what happened on that speaker’s stand seems to reference the work of one historian in particular—Frank L. Klement, whose 1993 book The Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery and Lincoln’s Address compiles years of papers and articles into one volume. When I read the book, I thought I’d hit pay dirt. It’s all there—platform sizes and locations, a who’s who of every VIP seated on the stand, and even the printed music of the songs that were performed during the ceremony.

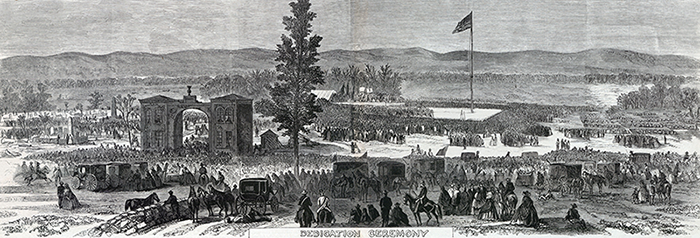

Because we don’t have a photograph of Lincoln actually delivering his address, many artists have tried to illustrate it over the years. The most compelling piece is by Joseph Becker, whose contemporaneous illustrations of Civil War scenes appeared regularly in publications throughout the war. His illustration of the consecration ceremony appeared as a centerfold in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in December 1863 and is a remarkable resource. [Fig. 2] In it, Evergreen Cemetery’s gatehouse serves as a doorway to the ceremony taking place up on Cemetery Hill. Here we can see the enormous crowd spread out over the grounds of both cemeteries. But Becker’s rendition of the speaker’s stand raises a number of questions we will need to answer.

At first glance, the photographic record of the consecration ceremony leaves much to be desired. Only six photographs of the actual ceremony are known to exist, and they all were taken at some distance from the speaker’s platform. In all of the views, the crowd of spectators, soldiers, and marshals on horseback obscure the physical stand. But once you begin to get your bearings and learn to decipher blurred images, these photographs are rich with detail and crucial information.

Civil War photography scholars have determined the six photographs were taken by three photographers: Two of the photographs were taken by Peter Weaver, who was based in Hanover, Pennsylvania. Weaver’s first photograph was taken from an upper floor window of the Duttera house, according to William Frassanito, a former U.S. Army intelligence analyst who made a name for himself as the expert on photography at Gettysburg. The Duttera house was located at the base of the hill on Steinwehr Avenue, where the Quality Inn now stands. This image looks uphill, past Taneytown Road, across the National Cemetery, and into Evergreen Cemetery. Several years ago, Bill and I were having drinks at the Reliance Mine Saloon, where Fraz (as his friends call him) keeps “office hours.” We were introduced to Fred Sherfy, who had something he wanted to show us. He pulled a folder out of a briefcase and produced this image—the only known original print of this photograph. I’d previously seen poor reproductions of it, which I was using on the project. [Fig. 3]

The details in this photograph are astounding. In the foreground you can see that the Dutteras’ backyard is being used as a parking lot for carriages. Up on the horizon you can see the gatehouse, the 90-foot poplar tree, the flagpole, the rise of the speaker’s stand, and even the platform that Alexander Gardner was using to take his photographs. Crouched on top of the platform is a human figure, which could be Gardner or his assistant. This photograph also offers a sweeping view of the fresh graves in the National Cemetery and helped us to determine which soldiers had been buried. At the time of the ceremony, only one-third of the soldiers had actually been buried.

The second photograph credited to Peter Weaver is this view of the ceremony taken from the second-floor rear window of Evergreen Cemetery’s gatehouse. [Fig. 4] In this somewhat washed-out photo, we’re looking uphill, across the grounds of Evergreen. Spectators are making their way toward the ceremony. To the right is the National Cemetery. As you can see, in 1863 there was no fence separating the two properties. To the left on the horizon, you can see the rise of the speaker’s stand. In the middle of the horizon is the flagpole. And over to the right, you can see a section of fresh graves on the National Cemetery side. You can also vaguely see Alexander Gardner perched high above the crowd on his photography platform.

Over the years of my research, I’ve become good friends with Brian Kennell, the superintendent of Evergreen Cemetery. During the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Brian allowed me to go up to the second-floor window in the gatehouse, where Peter Weaver took his photo. As I aimed my camera out the very same window at approximately the same time of day, 150 years later, I was able to understand why Weaver’s shot was washed-out—he was shooting directly into the sun.

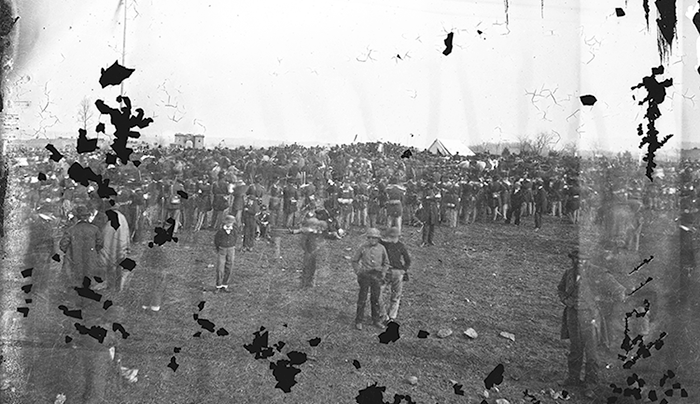

Three of the six Dedication Day photographs have been attributed to Alexander Gardner. (We are reproducing one of the images as Fig. 5.) Taken from high atop Gardner’s platform, these three views face northeast, across the National Cemetery and into Evergreen Cemetery. In the foreground, soldiers carrying rifles with fixed bayonets mill about while several boys who are fascinated by the camera are posing. Assistant marshals with white sashes are processing on horseback past the flagpole and toward the speaker’s stand. Beyond the line of horses is the gatehouse and the 90-foot poplar tree. You can see East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill off in the distance. The speaker’s stand rises up just in front of the “comfort tent,” which was provided for Edward Everett, who had suffered a recent stroke and had issues controlling his bladder. To the right of the tent is the parking area for the VIPs’ horses. Further to the right and beneath a stand of trees is the “Rocky Center,” which is where boulders were piled up after being excavated while digging graves in Evergreen.

When I remembered that Gardner or his assistant was visible in Peter Weaver’s photograph from the second-floor window of the gatehouse, I wondered if the opposite was true. The scan of this photograph was very high in resolution, so I took the image into Photoshop and zoomed way in. Sure enough, you can see Weaver’s box camera just inside the window, pointing in our direction. You can even see Weaver standing next to it! But there was yet another surprise in this photo. On the right side of the image, there’s a bearded man standing on the edge of frame. It looks like Alexander Gardner is photobombing his own photograph!

The final photograph of the ceremony, according to Bill Frassanito, was taken by a 19-year-old photographer named David Bachrach. Bachrach was positioned about 168 feet northwest of the front of the speaker’s stand. [Fig. 6] This photograph first came to the public’s attention in 1952, when Josephine Cobb, chief of the Still Photo section of the National Archives identified a photograph labeled “crowd of citizens, soldiers, etc.” as being the consecration ceremony of the National Cemetery. Knowing that Lincoln had to be in there somewhere, Cobb enlarged the negative plate several times and eventually found Lincoln seated on the platform. To Lincoln’s left is Secretary of State Seward. Edward Everett appears to be standing over to the right.

Now that I had all these 19th-century materials in hand, I turned my attention back to the size, shape and location of the speaker’s stand. According to Klement, the speaker’s stand was 12 feet wide and 20 feet deep. There were 30 VIPs seated in three rows of ten chairs each. Abraham Lincoln sat in the center of the front row, with Seward seated at his left and Everett seated at his right. How did Klement know the exact size of the platform? Because W. Yates Selleck said so.

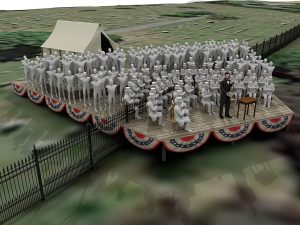

W. Yates Selleck had been appointed by the governor of Wisconsin to serve as a commissioner representing the soldiers from that state who were to be buried in the National Cemetery. As a commissioner, Selleck had a reserved seat on the platform, and he wrote that it was 12 feet wide and 20 feet deep. Not only did Klement accept the 12 by 20 measurement, he repeated that configuration 33 times throughout his book! Here’s what 12 feet wide by 20 feet looks like. Now add to it 30 chairs in rows of 10 each. We modeled these chairs after the ones on display in the Gettysburg Military Park Museum, which were said to have been on the speaker’s stand. As you can see, they don’t fit. Only eight chairs fit across, and that’s very tight. [Fig. 7]

Common sense tells us that Selleck’s measurement was wrong. In Joseph Becker’s illustration for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, we can see that the stand is a much larger platform than 12 by 20 feet. And there are over 100 people on it, many of whom appear to be standing on risers on the back half of the stand (see the rear, center of Fig. 2).

In the Gardner shot, we’re looking at the stand from the left side. We can see that this is much deeper than 20 feet. We can also see that many people standing on the platform appear to be elevated higher than the rest. It makes sense. If the folks in the back weren’t elevated, they wouldn’t be able to see what was happening up front. And folks in the crowd wouldn’t be able to see them. In the Bachrach photo, we can see that there are far more than 30 people on this stand and that many of them in the back are elevated. Clearly the speaker’s stand was significantly larger than 12 by 20 feet.

But take a look at something else in the Bachrach photograph. On the left side of the image there is a line of folks who are raised higher than the ones on the ground. That line flares out to the left. That’s the left edge of the platform. Now, notice we can see a similar flaring out on the right side of the platform, just past the seated governors. How is this possible? It defies geometry and laws of perspective. Unless the platform is actually shaped like a trapezoid. [Fig. 8]

Now we have room to place three rows of ten chairs each. In 1908, Selleck was asked to write down his memories of the Gettysburg Address. Forty-five years after the event, he recorded the names of thirty-nine VIPs who were seated on the platform. So now we need to add nine more chairs.

One issue did come up when we made this adjustment to the speaker’s stand. In the Gardner photos, I discovered you can actually see William Seward sitting on the platform in profile. While I was excited to have discovered images of Seward that had previously gone unidentified, it did raise another issue—why does Seward look like he’s sitting in the third row, when we know he sat in the front row? I stood in my office in front of a white board with a couple of my students trying to puzzle this out. We were coming up blank, until one of my students, Kenny Michaud, suddenly said, “Maybe they were sitting like an orchestra.” That would explain it. If they were sitting in a semi-circle, from the side it would look like the middle of the front row would be further back. It would also explain why the stand was shaped like a trapezoid. Looking more closely at the Bachrach photo, you can see the curve. The folks sitting on the ends are a little closer to camera than the ones in the middle.

We now have an approximate size, and we have a shape. Now we need to figure out where the platform was. And this question took years to figure out.

In his personal copy of the Revised Report of the Select Committee of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (1865), Selleck drew the location of his 12 by 20-foot speaker’s stand on a map inside the report. When this document was published by Civil War Times Illustrated in July 1976, it caused a bit of stir because Selleck’s location flew in the face of what, for over 100 years, had been the accepted, traditional position of the speaker’s platform—where the Soldiers’ National Monument now stands.

Klement dismissed Selleck’s location because it put the speaker’s platform downhill and close to where the New York monument stands today. Had the ceremony taken place there, the graves would have been behind the speakers stand and not in front of it. Eyewitness press reports placed the stand much higher on the hill, describing a “commanding view” of all the surrounding area. Most people took that to mean where National Monument stands. But according to one reporter who was there, the flagpole stood where “it is proposed to erect a national monument.” The flagpole and the speaker’s stand could not occupy the same space.

In 1978, Gettysburg National Military Park historians Thomas and Kathleen Harrison studied eyewitness accounts as well as the existing photographs and shocked historians when they declared that the speaker’s stand was much further uphill, where the Brown Mausoleum is located. This places the stand entirely within the borders of neighboring Evergreen Cemetery! This meant Lincoln wasn’t in the National Cemetery at all when he delivered his address. The main problem with this placement is that the Brown Mausoleum stands where that pile of boulders known as the “Rocky Center” was located. You could not build a stand there. But for years, some accepted this location.

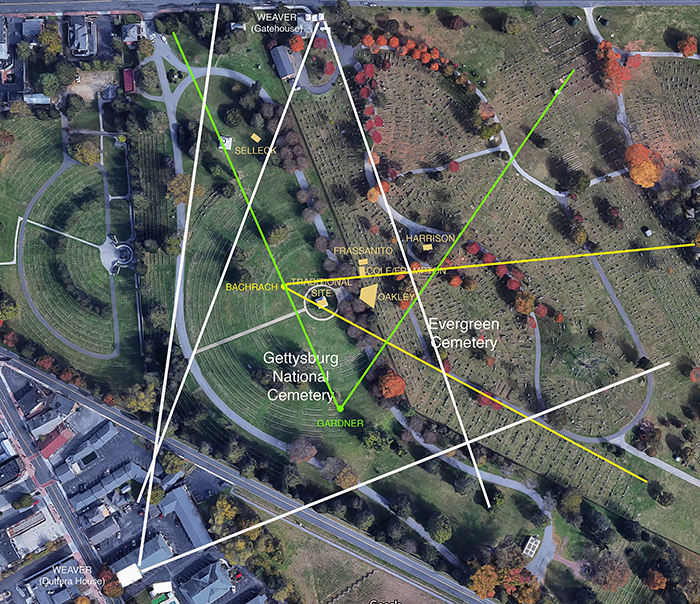

In 1995, when Bill Frassanito released Early Photography at Gettysburg, he placed the speaker’s stand within the confines of Evergreen Cemetery and listed the graves that formed the boundary of the stand. He made a convincing case, and for the past twenty-seven years, Frassanito’s placement of the platform has been regarded as the location.

Back at UNC Asheville, my team and I continued to build our 3D digital version of the cemeteries. Somehow, I got it into my head that it would be a cool opening for our video if we showed one of the photographs of the dedication ceremony and then had it dissolve into our digital recreation, with everything matching up. The digital cameras in Maya are designed to mimic real world cameras, from the focal lengths of lenses to the angles of view. This is how they blend live action actors into digital worlds in film. So, I decided to give it a try. But to make this work, I would need to know where the photographers actually stood. I always loved the Gardner view, so that was a good place to start.

In Maya, you can import a photograph onto something called an “image plane,” which sits like a piece of film in front of the digital camera’s virtual lens. Imagine putting a photograph you’ve taken back into the camera, then using that photograph to line up everything you can see in the photo with the real world. If you’re able to do it, you will be standing in the exact same position you were in when you took the photo in the first place. It seemed to me that if I could line up our digital world’s horizon line and the gatehouse and the flagpole with an analog photograph from 1863, our digital camera would be in the same place as Gardner’s camera when he took the photo.

It took a while, because I had to make hundreds of minute adjustments to our digital camera’s positioning, focal length, and angle of view in order to match the photograph. Here is the Gardner photograph and our digital recreation together. [Fig. 9] The horizon matches, the speaker’s stand matches, the flagpole matches, and the comfort tent matches.

Then it hit me—each of the photographers took their photos from very different positions that all triangulated each other. It stood to reason that if I could digitally match each photographer’s physical location, photograph, and angle of view (which is what their camera saw), I should be able to figure out the size, shape, and location of the speaker’s stand. Anything lying within each camera view would have to match the photograph. If it didn’t match what I was seeing through the digital lens, it wasn’t correct. If I matched an object’s size and shape, but moved it just a few inches from the correct location, it went out of alignment in every view. A piece of a jigsaw puzzle can only fit in its intended spot.

Because we know Weaver took one of his two photos from the gatehouse, I had a pretty good idea where to place him. I spent the next year trying to match Weaver’s position from the attic of the Duttera House. This was especially difficult because no photograph of the house itself seemed to exist—until I found the house in the background of a photograph of Ziegler’s Grove and Cemetery Hill which was taken around the turn of the century. The house had exactly what I was looking for—an attic window facing uphill.

The most difficult photo to match digitally was Bachrach’s photo taken from the front of the speaker’s stand. After almost three years of trial and error and a ton of frustration, I was finally able to match his position. Our digital speaker’s stand, the horizon, the comfort tent, and the flagpole all came into alignment. But there was a problem. I couldn’t match our stand-in digital humans with the real humans captured in Bachrach’s photo. The folks near the speaker’s stand almost matched. But the ones right in front of the camera were sinking into the ground up to their shins.

During one of my many visits to Gettysburg, Brian Kennell, the superintendent of Evergreen Cemetery, accompanied me while I was surveying the spot where I believed the speaker’s stand to have been. I kept staring at the ground and finally asked Brian if it was possible that the ground was lower in 1863. “Not only is it possible,” he replied. “It’s probable.” He explained that at the time of the ceremony, no graves had been established in this part of the cemetery. And when you dig a grave, you disturb the earth and raise the ground level. He pointed to the narrow alleys that separate the sections of graves, which were a good 6 inches to a foot lower, like the gutter in a bowling alley. “That’s the original height” he said. Armed with that information, I carefully lowered the ground level in our digital world about 8 inches. And suddenly everything fit! None of our digital humans looked like they were sinking in quicksand. The last piece of the puzzle fell into place.

Based on ten years of research and the fusion of 19th-century analog materials with 21st-century digital tools, I can now reveal what I propose is the size, shape, and location of the speaker’s stand.

The speaker’s stand was much larger than the accepted size, it was shaped like trapezoid, and it straddled both cemeteries. [Fig. 10] The back half of the platform stood in Evergreen Cemetery, while the front half, where the VIPs and Lincoln sat, was on the National Cemetery side. When Lincoln rose to deliver his Gettysburg Address, he was standing well within the grounds of the National Cemetery. I humbly submit that this isn’t just another educated guess. The 19th-century reporters, witnesses, illustrators, and photographers left us many clues. All we needed was the 21st-century technology, the patience, and the will to put it all together.

Using our digital model and cameras, we can trace what each photographer’s camera can see. Here is where each photographer took their photographs and their cameras’ angles of view. [Fig. 11] Everything outside of each of these cones is not in the photos. Everything within them is. As you can see, when viewed this way, we get a sort of Venn Diagram, which shows only one area where their views overlap. The “traditional” location is mostly within this central area, but the other stands fall outside of this intersection. Only the speaker’s platform that my research revealed falls completely within this central zone.

Does it really matter if we know where Lincoln was standing when he delivered his Gettysburg Address? Certainly, what he said matters more than where he said it. But I believe it does matter. Knowing you are standing on the very spot where Lincoln proclaimed that “government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth” ignites the imagination and transports you back in time. You become another witness to the event.

Nine years ago, my students and I explored Evergreen Cemetery for a couple hours, trying to find the Frassanito platform location. As we got closer and closer, I noticed that the students’ small talk and messing around had begun to taper off. I could sense their growing awareness of where they were. And by the time they were using their bodies to mark off the dimensions of the speaker’s stand at the location, there was absolute silence. It felt like we were standing on holy ground. I’ve had many of these students tell me over the years that they had very little interest in history when they joined the project. They were in it for the technical challenge. But by the time their work on the project had come to an end, they’d all become history buffs. Digital humanities was the gateway to a world they had not yet explored and the journey for us all was incredibly immersive.

Does it really matter if we know where Lincoln was standing when he delivered the Gettysburg Address?

Absolutely.

Christopher Oakley is a professor of new media at UNC Asheville. His entire presentation, which includes more images than could be reprinted here, can be viewed at www.c-span.org.