Lost to History: Abraham Lincoln’s Act to Encourage Immigration

Lost to History: Abraham Lincoln’s Act to Encourage Immigration

By: Jason H. Silverman

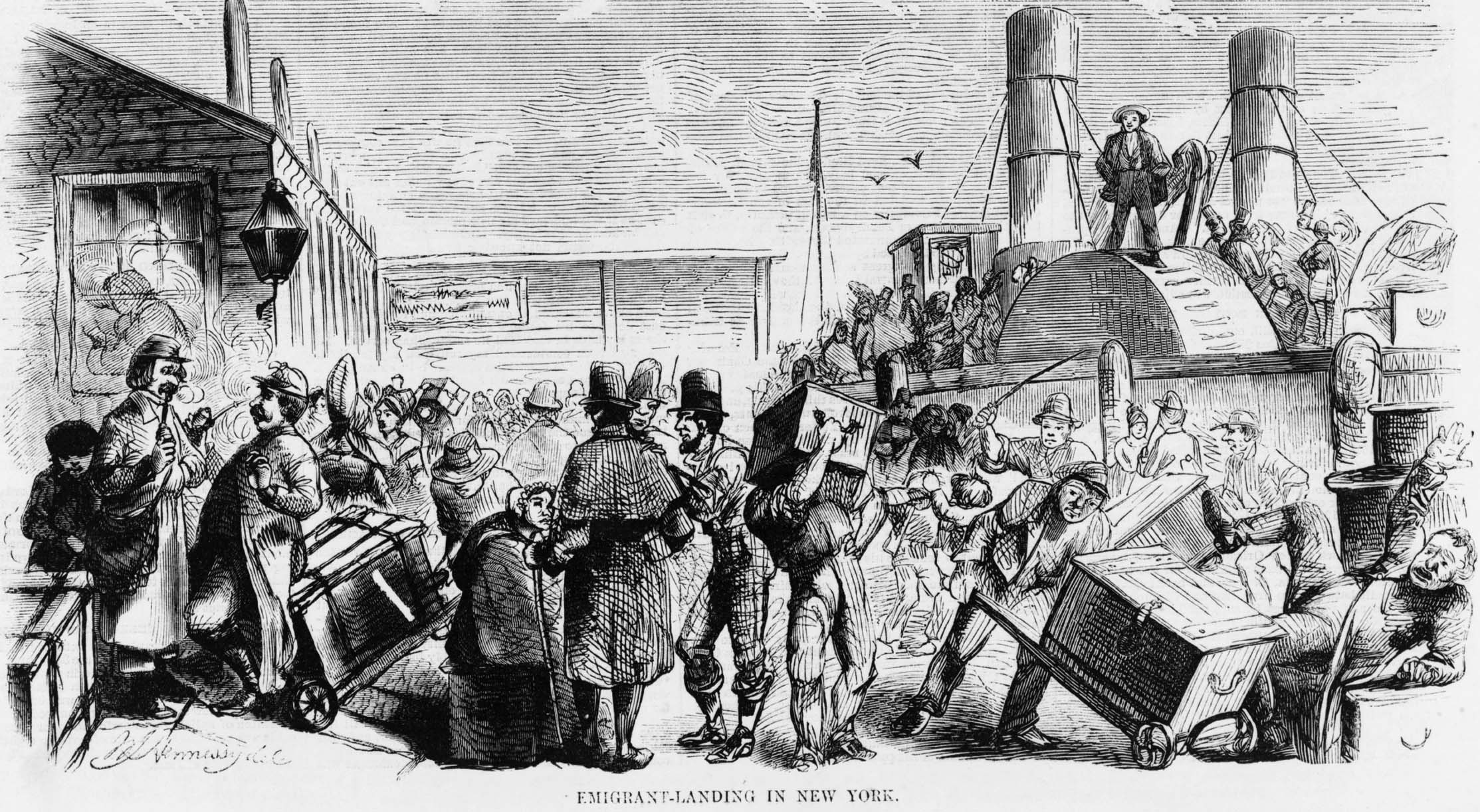

Sometimes it’s difficult to believe that anything Abraham Lincoln did was lost to history. But historians have overlooked one of President Lincoln’s signature pieces of legislation, The Act to Encourage Immigration, July 4th, 1864, the first, last, and only major law in American history to encourage immigration. Given that the controversy over immigration commands the news today on a daily and global basis, this is, sadly, a significant omission of an act that President Lincoln saw as the bright future of the United States.

Long before he spoke about the evils of slavery, Abraham Lincoln spoke about the need for free labor, and he consistently articulated an economic philosophy that relied heavily upon immigrant labor. From his earliest speeches on, Lincoln saw immigrants as the farmers, merchants, and builders who would contribute mightily to the economic future of the United States.

Lincoln realized that only a concerted effort under the control of the federal government, which could greatly facilitate both voluntary and recruited immigration, could hope to mitigate the labor shortage caused by the Civil War. By so doing, proponents of immigration could unite their forces in a major drive for the Federal government’s encouragement of immigrant labor.

Lincoln was not alone in his beliefs. As early as 1819, Congress passed a law designed to improve the condition on the ships for passengers coming to the United States. Additional legislation was passed to regulate the carriage of passengers on vessels in 1847, 1848, 1849, and 1860. By theoretically protecting passengers, such legislation tended to encourage immigration and provide a precedent for Federal encouragement of immigration. The demand for a Federal department of immigration was first voiced in 1854 in a platform issued by the Free Germans at Louisville, Kentucky. But such demands were weak and isolated until the Civil War created an acute need for labor.

Yet, the war did not immediately serve as a catalyst for efforts to encourage immigration. The mobilization and organization of a growing Union Army, the constant demand for war materiel, and the introduction of Greenbacks into circulation all served together to raise prices and stimulate employment. Soon there were few unemployed.

But that did not stop John Williams, editor of the pro-labor Hardware Reporter (a source largely overlooked by historians), from launching a vigorous campaign in 1863 for the immigration and recruitment of iron and steel laborers from abroad. Williams advocated a program for immigration, without cost to the immigrant, of all able-bodied workmen and their families. “No investment of the nation’s funds,” said Williams, “could be half so profitable as this or be made to yield so large an interest.” Williams asserted that American labor’s “scarcity and consequent high price is the great impediment now to industrial progress in this country.”

Williams’ appeals fell on deaf ears save for those of President Lincoln. In his annual Message to Congress on December 8, 1863, Lincoln called for government intervention in recruiting immigrant labor. “I again submit to your consideration the expediency of establishing a system for the encouragement of immigration. Although this source of national wealth and strength is again flowing with greater freedom than for several years before the insurrection occurred, there is still a great deficiency of laborers in every field of industry, especially in agriculture, and in our mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals,” Lincoln wrote. “While the demand for labor is thus increased here,” he continued, “tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupation, are thronging our foreign consulates and offering to emigrate to the United States if essential, but very cheap, assistance can be afforded them. It is easy to see that, under the sharp discipline of civil war, the nation is beginning a new life. This noble effort demands the aid, and ought to receive the attention and support of the government.”

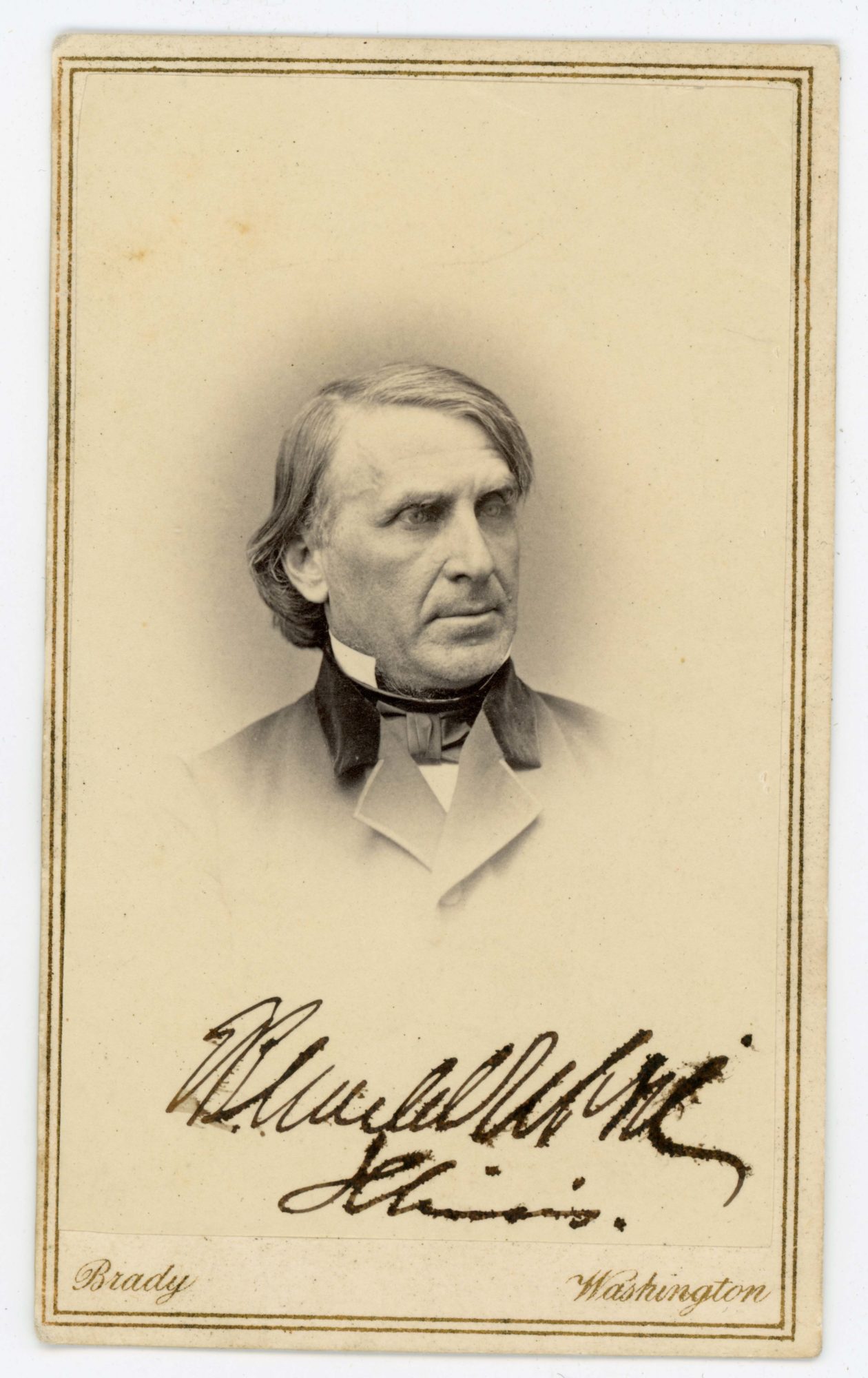

To his pleasure, Lincoln’s words resulted in Congressional activity. Within a week, a bill to encourage and protect foreign immigrants and to make more effective the Homestead Act, which had become law on May 20, 1862, was presented in the Senate by Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy of Kansas. That same day on the other side of the Capitol, Representative Elijah Ward, of New York, presented a resolution creating an Immigration Bureau which was passed and referred to the Committee on Agriculture. Little more than a week after Lincoln’s Annual Message to Congress, his plans for immigration appeared headed for passage when it was referred to a special committee of five on emigration, chaired by fellow Illinoisan Representative Elihu B. Washburne.

By February 18, 1864, John Sherman, chairman of the Committee on Agriculture in the Senate, submitted a bill to encourage immigration. Sherman echoed Lincoln’s words by emphasizing that the encouragement of immigration was of the highest importance for the Federal government because of the acute need for labor in industry created by war and its accompanying draft.

The committee, however, rejected that portion of the bill which asked for the establishment of a Bureau of Immigration, the appointment of a large number of salaried officers, and an appropriation of $125,000, because of the great expense involved. A petition for incorporation from the North American Land and Emigrant Company was rejected as well because of apparent self-interest. Any bounties to the immigrant or the payment of passage money were similarly rejected.

After much political wrangling, Lincoln’s immigration bill finally passed the Senate on March 2, 1864. It provided for a Commissioner of Immigration, under the auspices of the State Department, who was to encourage immigration by recruitment. The Commissioner was to correspond with various American consuls, who were expected to collaborate with him in his work. An office was to be established under a Superintendent in New York City whose duty it was to protect immigrants from fraud and to make contracts with railroad companies for the transportation tickets to be paid for by the immigrant. He was also to see that the provisions of the Passenger Act protecting immigrants were enforced. Fifty thousand dollars were to be appropriated for the implementation of this bill.

On the House side, Representative Ignatius Donnelly of Minnesota spoke in support of the immigration bill emphasizing that the need for labor was so great that private companies had sought to remedy it by establishing societies in Boston and elsewhere to encourage and facilitate immigration. “Let us stimulate, facilitate and direct that stream of immigration,” asserted Donnelly, “[let us] throw wide open the doors to emigration…and in twenty years the results of the labors of the immigrant and their children will add to the wealth of the country a sum sufficient to pay the entire debt created by this war.”

In April, Washburne’s House committee reported, “The vast number of laboring men, estimated at nearly one million and a quarter, who have left their peaceful pursuits and patriotically gone forth in defence of our government and its institutions, has created a vacuum which has become seriously felt in every portion in the country. Never before in our history,” Washburne stated, “has there existed so unprecedented a demand for labor as at the present time. This demand exists everywhere. . . . There are twenty railroads in process of construction or under new contract in the west alone, which would furnish employment for twenty thousand laborers. The construction and repair of railroads in other sectors of the country will give employment to ten thousand more. It is believed that the demand for laborers on our railroads alone will give employment for the entire immigration of laborers in 1863.”

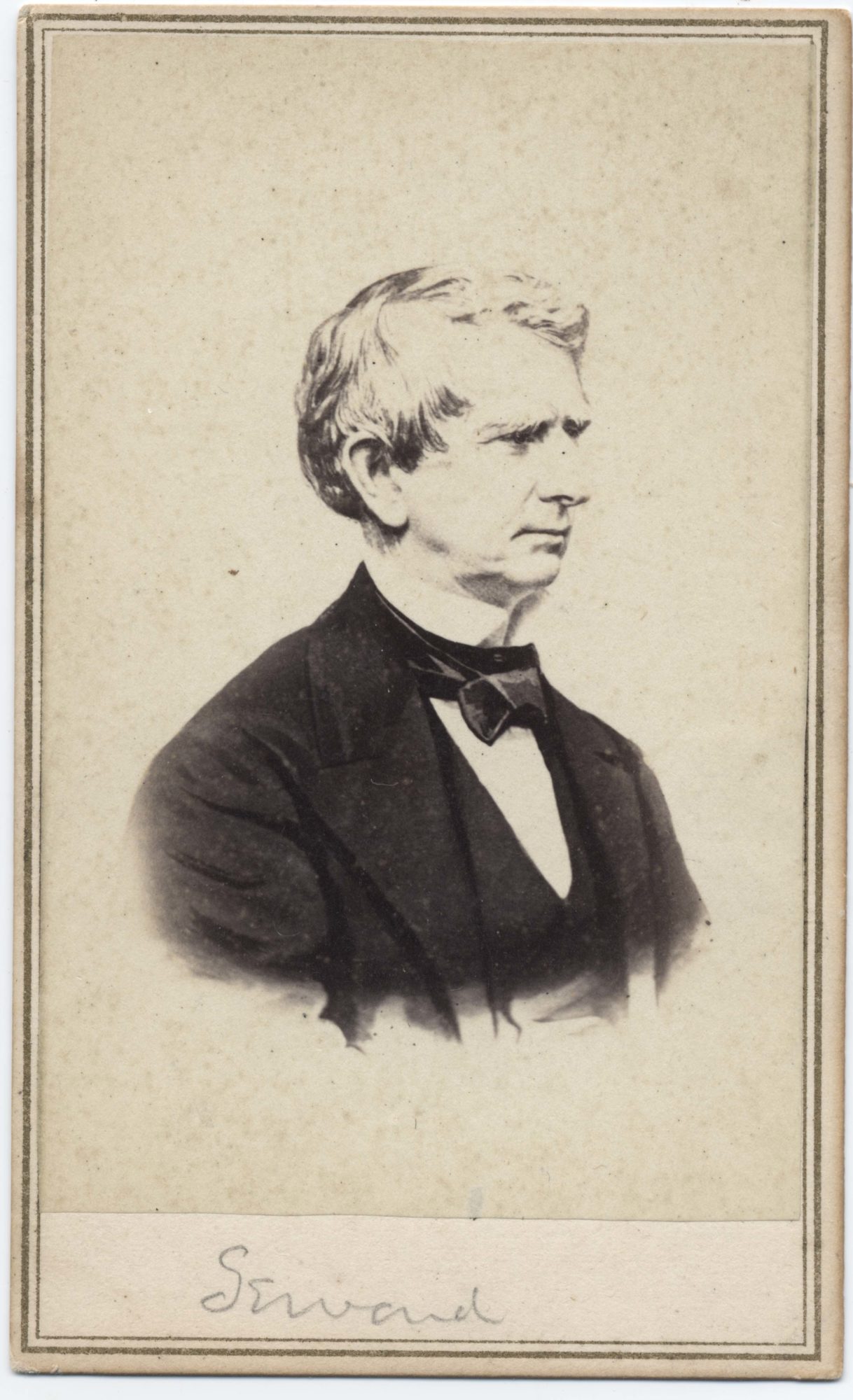

The committee acknowledged that many suggestions embodied in Lincoln’s bill had, in fact, been made by Secretary of State William H. Seward. In a letter to the Special Committee dated March 30, Seward suggested that the facilitation of immigrant transportation was the major problem to be solved. His solution provided for an increase in the number of vessels engaged in the transportation of immigrants and in the adoption of a system which would enable the immigrant to make passage by use of credit under an obligation to repay the cost out of whatever salary was earned after reaching the United States. Seward believed it would be best, therefore, to put a system in place which would provide for the pledging of a portion of the immigrant’s wages. The Secretary felt that under the existing Homestead Law a “certificate might be issued which would entitle the immigrant to . . . a party who should advance the means of emigration.”

Seward’s suggestions were ultimately embodied in a bill which passed the House on April 21, 1864. The Senate, however, apparently disapproved of several elements of the House bill, but with President Lincoln’s urging, ceased its delaying tactics and approved it on July 2, 1864. Two days later, Lincoln signed the immigration bill which became law appropriately and fatefully on July 4, 1864.

The Act in its final form consisted of eight sections and authorized President Lincoln, with the consent of the Senate, to appoint a Commissioner of Immigration for a term of four years at $2,500 per annum, a figure considerably more than the average annual income in the United States at that time (only 3% of the population earned more than $800 a year). Notable aspects included the second section which provided in part “That all contracts that shall be made by emigrants to the United States in foreign countries, in conformity to regulations that may be established by the said commissioner, whereby emigrants shall pledge the wages of their labor for a term not exceeding twelve months, to repay the expenses of their emigration . . .” The third section significantly exempted all immigrants arriving after the passage of the act for compulsory military service unless the immigrant voluntarily renounced under oath his allegiances to the country of his birth and declared his intention of becoming a citizen of the United States. The fourth section provided for the establishment of a United States Immigrant Office in New York City, under a Superintendent of Immigration with an annual salary of $2,000. And the concluding section appropriated $25,000 or any part of it, to be used at the discretion of President Lincoln.

Lincoln’s major supporter in his endeavor, the Hardware Reporter, welcomed his law enthusiastically. “Future historians,” predicted an editorial, “will assign a most important place in history” to his effort. “Surely no more profitable use of the people’s money could be made in expending a moderate sum in facilitating emigration of a large number of laborers, especially skilled workers, to this country. We hope, “the editorial continued, “Congress will promptly do its duty but meantime let not the employers of labor remain idle, but rather by combined and systematic effort seek to influence at once an increased volume of emigration from Europe.”

Lincoln’s message seems to have quickly motivated at least one consular agent, William Thomas, Jr., stationed at Gothenburg, Sweden, who wrote to the Assistant Secretary of State, Frederick W. Seward, that he was encouraging Scandinavian emigration by widely distributing information. He reported that the inability to pay for a passage to America was the one great obstacle on the part of those who would otherwise seek a new life in America. “I am well aware,” wrote Thomas, “that as consul I can have nothing to do with enlisting soldiers, but no international law can prevent me from paying a soldier’s passage from here to Hamburg out of my own pocket.”

Through the Secretary of State, the New York Chamber of Commerce received the suggestions contained in Thomas’s letter, which was read at a meeting of the Union League of New York on May 12, 1864. “The subject of emigration,” the League reported “…has become in consequence of the Rebellion, a Natural Question of vast magnitude, and has engaged the serious attention of the Government… [which] looking upon the matter simply in a pecuniary point of view, could make no better nor surer investment, than in importing emigrants at the National cost, whose labor would directly or indirectly restore the advance fourfold.”

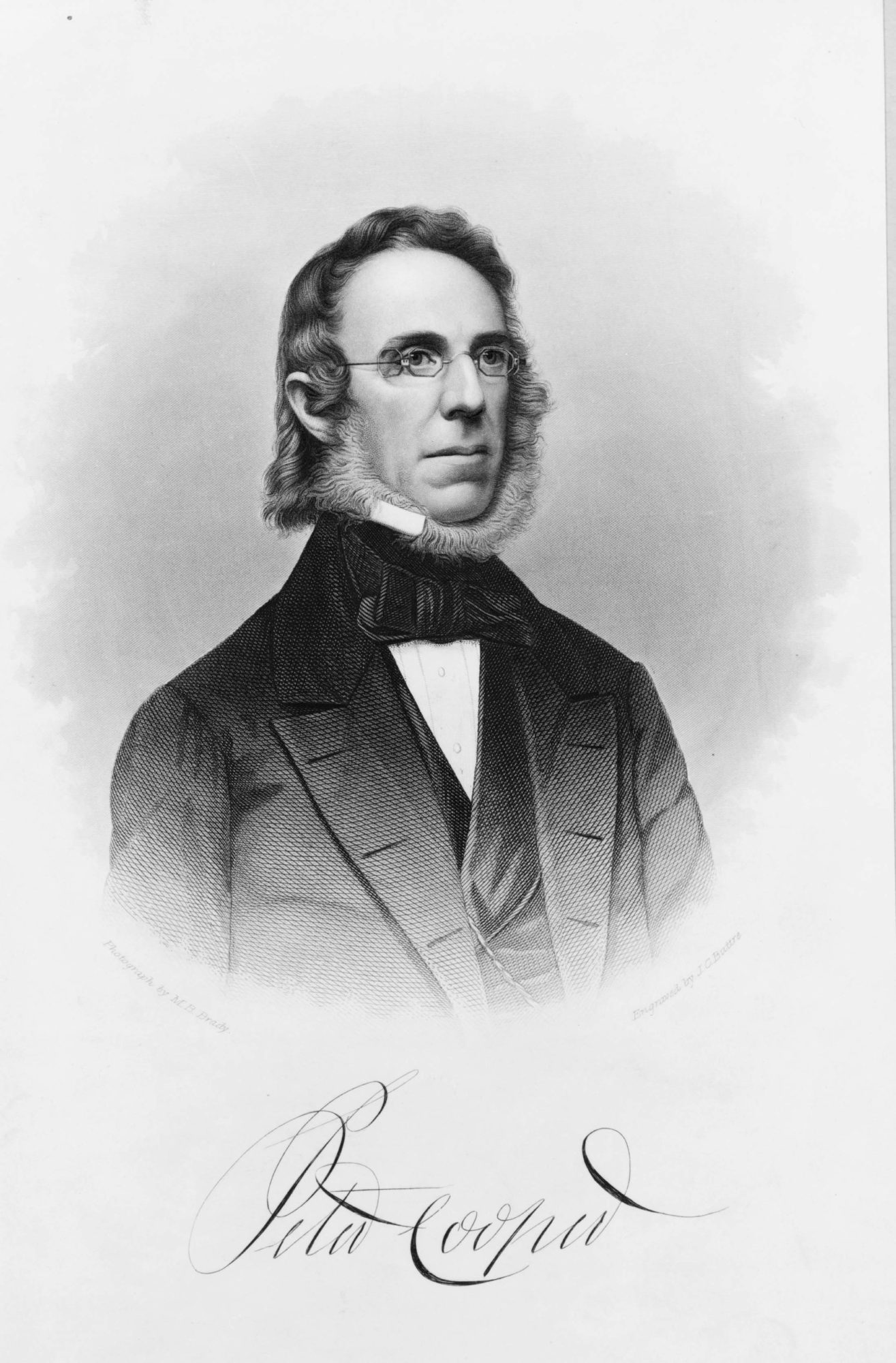

Soon thereafter, John Williams addressed an open letter to New York industrialist Peter Cooper, with the purpose of generating support for the new immigration law. Williams strongly maintained that the obligation rests with the government to provide the financial means to support the immigration of labor. “It is a matter of national interest,” wrote Williams, “and should be provided for at national expense….” There was considerable self-interest evident in this letter as Williams had already sent agents to Ireland and Germany to recruit labor.

So strong had the movement for the federal financing of immigration become that, at Lincoln’s urging, the 1864 National Union Convention, or the Republican Party, in its convention at Baltimore wrote into their platform a plank stating: “That foreign immigration, which in the past has added so much to the wealth, development of resources and increase of power to this nation, the asylum of the oppressed of all nations, should be fostered and encouraged by a liberal and just policy.”

While The Act to Encourage Immigration of July 4, 1864, did not provide for the establishment of a Bureau, the State Department under William Seward used its own discretion and created the Bureau of Immigration. By August, the Bureau was already extremely active. During its short lifetime of three years, it had four Commissioners of Immigration assigned to Washington, and one superintendent, John P. Cumming in New York City, subordinate to the Commissioner.

The letter books and the annual reports of the Immigration Bureau show that its work included almost every type of activity to increase immigration. Notably, it published and widely circulated a pamphlet in English, German and French. Secretary of State Seward oversaw all Bureau activities through his department and its vast consular network.

The Immigration Bureau, however, was not opposed to outsourcing labor recruitment, and, in several instances, the Bureau asked private firms, especially the American Emigrant Company in New York City, to bring immigrants to America under contract. For example, replying to requests from Scotch handloom weavers, French workers, and Austrian laborers who petitioned President Lincoln for free transportation to the United States, the Immigration Bureau replied that it had no authority to pay for their passage, but that they would contact private agencies on their behalf.

The Federal Bureau of Immigration did not keep in close contact with the various state and private immigrant agencies, but it did work very closely with the American Emigrant Company. Perhaps too closely in fact, as this relationship contributed significantly to the Bureau’s ultimate demise. When The Act to Encourage Immigration was passed, the privately funded American Emigrant Company established an office in New York City at No. 3 Bowling Green. “This company will be the handmaid of the new Bureau of Immigration,” said an editorial in the Hardware Reporter, “applying private enterprise just at the point where official interference becomes impracticable.” This observation most assuredly was an accurate one. For, when the Federal Bureau of Immigration established its office in New York City it chose the exact same location as the American Emigrant Company. In an attack upon the Bureau of Immigration made on the floor of the Senate, Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont railed that,

“…All on earth that this Bureau of Immigration has done since 1864 is to act in harmony and in such subordination to that emigration aid society. . . . The Commissioner or Superintendent of Immigration has held his office in their office. He has cooperated with them. . . . They have made the contracts for foreign labor and sent out for foreign immigrants and he has satisfied those contracts…He, then, paid by the Government of the United States, has done nothing else, . . . but cooperate with the immigrant company in New York to render that company efficient and enable them through the power of the General Government, to enforce the contracts which they make in foreign countries for the importation of labor. I submit that that is not a very dignified business for the Government of the United States anyway.”

The Letter Books of the Bureau show that Morrill was indeed correct about collusion between the two agencies. The records clearly indicate that there was regular communication of questionable ethics between them. This unholy alliance became so flagrant that one of the Federal Immigration Bureau Commissioners, E. Peshine Smith, became a special contributor to the Iron Age, the official publication of the American Emigrant Company.

However, it is unfair to say that the work of the Federal Bureau of Immigration during the Civil War was without merit. It effectively directed immigrants to that section of the country where there was a shortage of labor and where their work could receive the highest wages. To accomplish this, the Bureau sent letters to more than one thousand agricultural societies requesting a statement of wages paid to the mechanics, artisans, and common laborers. From these replies the Bureau prepared a recruitment statement of the average wages paid in the states to each branch of industry. Through its superintendent in New York and in other port cities as well, each arriving immigrant was given this information.

When these statistics became outdated at the close of the war, the Bureau changed strategies under the direction of Horace Newton Congar, a New Jersey attorney, journalist, and diplomat (Lincoln had appointed him Consul to Hong Kong, China in 1861). The Bureau circulated a recruitment pamphlet in Europe and initiated a policy of active cooperation with all states and territories to encourage immigration. Toward this end, the Bureau strongly encouraged the states and territories, including southern states after April 1865, to establish immigration bureaus; to put the leadership of these recruiting activities into the hands of the Federal Bureau; and to offer all the services of the Bureau through the office of the Superintendent of Immigration and the consular network of the United States Government. In South Carolina, Virginia, Louisiana, and Nebraska territory, the Bureau was an important presence in the establishment of their agencies to encourage immigration. In Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Oregon, the Governors replied that legislation to create immigration agencies was pending or would be submitted to the legislature.

To consolidate its control over immigration, the Bureau, under the leadership of Commissioner Congar, prepared a pamphlet containing pertinent documents, facts, and figures. Thirty thousand copies of this pamphlet were prepared and sent abroad under the direction of the Secretary of State to the American Consuls. The Consuls were strongly advised that “in all your proceedings you will studiously take care not to contravene the laws, policy or sentiments of the government to which you are accredited, or to excite any unkindly feelings on the part of the government or the people of that country.”

Trouble developed almost immediately. Within a month, the American Minister at Paris, John Bigelow, received a note from M. Drouyn de Lhuys, the French Foreign Minister, who objected to the “inconveniences” in authorizing the distribution of documents which “present the character of fair appeal in favor of emigration. . . . The French administration had always been opposed,” said de Lhuys, “to [recruiting] among the native-born operatives; besides . . . it would create a precedent of which emigration agencies belonging to other nationalities might avail themselves . . . . “ The French refused to cooperate under their law of July 18, 1860, which prohibited any efforts to promote emigration without permission from the minister of Agriculture, Commerce, and Public Works. To avert an international incident, Secretary of State Seward immediately notified Bigelow to direct consuls to refrain from any actions objected to by the French government and laws of France. The Bureau of Immigration in Washington soon thereafter curtailed its overseas recruitment of immigrants.

Obviously, Lincoln’s signature immigration law encountered some rough patches during its first few months. For example, the Immigration Bureau could not effectively enforce the passenger laws; private companies were dissatisfied with the contract provisions of the law; and the many frauds perpetrated upon immigrants resulted in strenuous efforts to amend The Act to Encourage Immigration. In the last Annual Message to Congress that he would send, on December 6, 1864, President Lincoln himself observed, “The act passed at the last session for the encouragement of immigration has, so far as was possible, been put in operation. It seems to need amendment which will enable the officers of the government to prevent the practice of frauds against the immigrants while on their way and on their arrival in the ports, so as to secure them here a free choice of avocations and places of settlement.” A successful immigration process was of paramount importance to Lincoln who continued in his message to Congress, “A liberal disposition towards this great national policy is manifested by most of the European States, and ought to be reciprocated on our part by giving immigrants effective national protection. I regard our emigrants as one of the principal replenishing streams which are appointed by Providence to repair the ravages of internal war, and its wastes of national strength and health.”

In the Senate on January 23, 1865, a bill to amend The Act to Encourage Immigration and amend the Passenger Act of 1855 was referred to the Committee on Commerce. The Senate as a whole took no action on that bill or on a similar bill proposed the next month by Representative Elihu B. Washburne which had passed the House of Representatives.

Lincoln did not live to see the activity in the next session of Congress where both houses acted. An act introduced by Representative William Augustus Darling of New York on April 9, 1866 “to amend the act to establish a Bureau of Immigration,” substantially the same bill that had been introduced into the previous Congress, again passed the House. Both Secretary of State Seward and Immigration Commissioner Smith approved of this bill.

The Senate considered the House Bill on July 23, 1865. But to the shock and dismay of all of its supporters, the Senate Committee on Commerce unexpectedly added an amendment to strike out the entire bill after the enacting clause and to insert the following: “That the Act entitled An Act to Encourage Immigration, approved July 4, 1864, be and is hereby, repealed.” Senator Morrill, speaking for the committee, sharply condemned the Act of 1864 and soundly criticized the passage of a bill which, he said, put the Government in the business of importing men. “This is closely allied to coolie business,” said Morrill, “it encourages a species of slavery, so much so that the Committee was astonished that the Senate ever gave it a moment’s consideration. The Bureau, continued Morrill, “did nothing more than act in harmony with and subordinate to the private [American Emigrant Company] in New York.”

This action in the Senate marked the end to President Lincoln’s dream to see America encourage immigration. The visceral criticism of his law during the Senate debate sounded the death knell on the only act the Federal government ever passed to encourage immigration.

Opposition came from organized labor as well. At the Congress of the National Labor Union in 1867, a delegate attacked the American Emigrant Company as “a perfect pack of swindlers. . . The sooner that system of swindling is abolished, the better.” Indeed, the same Congress that ended Lincoln’s hope for a hospitable welcome to newcomers “brought out a number of facts relative to the activities of the American Emigrant Company in providing strike breakers for employers, as well as the part which the American Consuls aboard were playing in it.” Obviously, then, the Senate succumbed to the pressure exerted by organized labor when they suddenly killed The Act to Encourage Immigration.

Lincoln’s law was finally and officially repealed by a section of the Diplomatic and Consular Bill in 1868. No other action was ever taken by any Congress to encourage immigration, although two bills were introduced in 1868 purporting to establish immigrant societies abroad under government direction and several states later petitioned Congress for laws to encourage immigration.

Lincoln never saw at least the temporary and sporadic fulfillment of his dream that America would welcome immigrants to its shores as a natural resource and a valuable element in the nation’s economic success. Yet he nevertheless deserves the credit for initiating a plan that personified Emma Lazrus’ words long before they were memorialized on the Statue of Liberty. By so doing, the Great Emancipator became also the Great Egalitarian who believed firmly that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution applied to all, regardless of their ethnicity or country of origin. What set Lincoln apart from most of his countrymen was his ability to look past what his society told him a foreign person or group must be like and to trust his own assessments instead. This is precisely what most Americans of Lincoln’s generation could not do then, and many Americans cannot do now. And perhaps therein resides the former rail-splitter’s greatest attempt to mitigate America’s relentless and acrimonious controversy over immigration.

Jason Silver is the Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History Emeritus at Winthrop University.