Lincoln & the League

Lincoln & the League

By Allen Guelzo

The Union League of Philadelphia has occupied the grand corner of Broad and Sansom Streets in Philadelphia since 1865, and, though it remains today one of the most vibrant social and professional organizations in the city, it takes great pride in putting its Civil War-era origins on display from the moment a visitor walks through the door.

The League was the brainchild of the well-heeled Philadelphia poet and playwright George Henry Boker. Although Philadelphia was a Northern city, it had substantial commercial ties to the South, and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 placed a severe strain on its loyalties. The Democratic state convention adopted as part of its platform in 1862 its opposition to a war which “seeks to turn the slaves of the Southern States loose to overrun the North and enter into competition with the white laboring masses, thus degrading and insulting their manhood by placing them on an equality with Negroes in their occupation….”[1] While Boker’s enthusiasm for Lincoln never wavered, the decay of the Union’s military fortunes and the rising tide of disaffection in Philadelphia over emancipation depressed and dispirited him.

On November 10, 1862, shortly after the disastrous midterm Congressional elections, Boker met Judge John Innes Clark Hare on Seventh Street, and poured out his woes “into a conversation that was little more than a comparison of sorrows.” What particularly galled Judge Hare was that while “we, the inhabitants of a loyal city were cast down before the ill fortunes of our country, men who were almost in league with the Southern traitors were walking with heads high among our people.” Hare proposed, as at least one remedy, a new organization of Republicans and pro-war Unionist Democrats, and Boker was sufficiently taken with the idea that he enlisted the aid of Morton McMichael, the editor of the Philadelphia North American, and Philadelphia jurist Benjamin Gerhard, as founders and organizers.

After a series of small preparatory meetings for the creation of a “Union Club,” beginning at Gerhard’s home at 226 South Fourth Street, an assembly of over fifty Unionists — Republicans and Democrats alike, including Horace Binney, Jr., and pro-Union Democrat Daniel Dougherty — met at the home of John F. Meigs on December 27, 1862, and adopted articles of association for a ‘Union League of Philadelphia.’ Its only condition of membership was “unqualified loyalty to the government of the United States, and unwavering support of its efforts for the suppression of the Rebellion,” and its primary task was to be “to discountenance and rebuke by moral and social influences all disloyalty to the Federal government….” As a headquarters, the new League would rent space in a former private mansion at 1118 Chestnut Street (where Lincoln himself would pay a call during his 1864 visit to Philadelphia) then at 1216 Chestnut; in 1865, it would move into a spacious Second Empire-style building on Broad Street.[2]

In the decades after the Civil War, the Union League remained a center for Republican and conservative politics in Philadelphia. But it also remembered its origins by accumulating an impressive collection of art related to Lincoln and the Civil War, and has continued to commission works celebrating its founding (most recently, a portrait of Frederick Douglass). Among its most famous objects are the two great paintings of Xanthus Russell Smith, which grace the League’s main hallway, The Monitor and the Merrimack (1869) and The Kearsarge and Alabama (1875). But Abraham Lincoln has always owned the core of the League’s memory: each year, it commemorates Lincoln’s birthday with a parade along Chestnut Street to Independence Hall for a wreath-laying at the site where Lincoln raised the flag on February 22, 1861, and bestows its Lincoln Award on prominent Americans.

Its greatest Lincolnian gems are the more than thirty pieces of Lincoln-related art on display (or in archival safe-keeping) in the League House. And the single most beloved example of Lincolnian art is the famed 1863 Lincoln life portrait by Edward Dalton Marchant, which hangs in a place of honor in the League House’s great ballroom, Lincoln Hall. Marchant was Philadelphia-based and a student of Gilbert Stuart who specialized in portrait painting, from the jurist Horace Binney to the economist Henry Carey. Marchant would join the League in 1865, so it was not difficult for “a large body” of Lincoln’s “personal and political friends” to turn to Marchant for a formal portrait that would be displayed in Independence Hall.[3]

Marchant began work on the portrait in the White House in February, 1863, and worked “for several months” there, accompanied by his son Henry, a captain on leave from the 23rd Pennsylvania. (Henry Marchant would be killed in action at Cold Harbor a year later.) Marchant enjoyed “daily communication with the remarkable man whose features I sought to portray,” although Marchant found capturing Lincoln’s deep and varied moods a challenge. “He was seldom twice alike,” Marchant wrote to a fellow artist, and he found Lincoln “the most difficult subject” he’d ever painted.[4]

The result, however, is a glowing triumph. Marchant painted Lincoln at three-quarters, his right hand at his side holding a quill pen, his left arm and hand resting on a table with a copy of a document, beside an open inkwell. Behind Lincoln are the pillars of the state and the foot of a Columbia-like figure (Marchant called it ‘the Goddess of Liberty’) with a broken chain hanging down. The unspoken message is about emancipation, and Marchant intended the document beneath Lincoln’s left hand to represent the Proclamation. (Lincoln had issued the final Emancipation Proclamation only two months before Marchant started work, and Marchant described it as “the great, crowning, act of our distinguished President.”) Lincoln’s eyes are somber, reflective, cast slightly downwards and focused at a point beyond the right margin of the canvas, as if contemplating the enormity of the Proclamation’s consequences. But the most striking detail is the formal white tie—the only occasion in either portraits or photographs where Lincoln is seen wearing one. Marchant noticed that Lincoln only rarely wore a white “cravat.” But Marchant decided that Lincoln’s usual black tie looked too much “like a gash” that “seemed to sever the head from the body,” and the white tie is rendered in exquisite detail.[5]

Marchant employed another Philadelphian, the engraver John Sartain, to create a mezzotint print for popular sale. Sartain added some slight details to the print version (the word LIBERTY, which appears faintly in the painting on the Goddess of Liberty’s pillar is more pronounced in the print), but Marchant was delighted with the public demand, and in 1865 arranged for Louis Haugg (also of Philadelphia) to produce an inexpensive lithograph which sold “fully up to a thousand a day.”[6]

Even more imposing is a seven-and-a-half-foot statue of Lincoln which forms the centerpiece of the Lincoln Memorial Room. It was the creation in 1916 of the Swiss-born sculptor Jacob Otto Schweizer, who had emigrated to the United States in 1894. The League had undergone a major physical expansion, growing to occupy an entire city block between Broad Street and Fifteenth Street, and a substantial room, the Banquet Room, on the second floor was dedicated to Lincoln and the League’s Civil War veterans. The west wall of the room featured rich paneling that bore medallions of eight Union commanders—Gregg, Hancock, Sheridan, Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Meade and Farragut — and bronze plaques with the names of the League’s 531 veterans, with the words of the Gettysburg Address carved in gold leaf across the top. But the centerpiece of the wall was Schweizer’s Lincoln, raised on a two-step marble dias, enfolded in a concave marble niche.

If Marchant’s Lincoln was the Emancipator, appearing thoughtful and serious, Schweizer’s statue was the Commander-in-Chief, drawn up to his full height, his right hand resting on a flag-draped rostrum, the left clenched in a defiant fist, as if in the act of proclaiming that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Lincoln stands upon a square pedestal, with an allegorical frieze on each side depicting Government, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, and the League’s motto Amor patriae ducit (Love of Country Leads) inscribed in the niche. The guest of honor for the dedication of the Banquet Room was to have been Corporal James Tanner, who achieved a moment of unplanned glory on April 14, 1865, as the stenographer whom Secretary of War Edwin Stanton conscripted to record in shorthand the testimony of witnesses to Lincoln’s assassination, even as Lincoln lay dying. Tanner was unable to attend, but he made the occasion memorable by presenting to the League his manuscript shorthand notes from that bloody evening.[7] The League also owns a maquette of the Schweizer statue, and 14-inch-high copies of the statue are bestowed as the symbol of the League’s Lincoln Award.

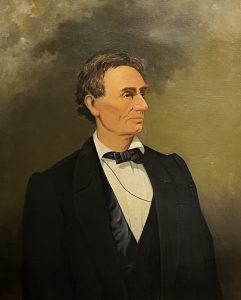

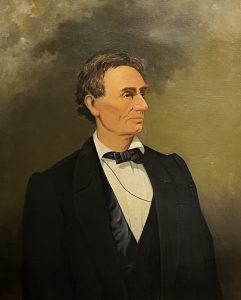

One other Lincoln portrait graces the League’s walls in the Banquet Room where portraits of almost every Whig and Republican president (and one unlikely Democrat: Andrew Jackson) are hung. It is, however, an unlikely portrait, coming from the brush of Xanthus Smith, especially since Smith never seems to have had any personal acquaintance with Lincoln. The 36”x29” portrait is, in fact, a rendering on canvas of one of the series of dramatic photographs of Lincoln taken by the Chicago photographer Alexander Hesler in 1860. Like the Hesler photographs, Smith shows the still-beardless Lincoln in profile, but now against a background of stormclouds.

Smith’s reputation rests largely on his fifteen paintings of Civil War naval scenes; portraiture was not his strong suit. The son of a painter of theater scenery (and sometimes landscapes), Smith had his first commission—a modest landscape of a neighbor’s property – in 1854, at the age of fifteen. He joined the U.S. Navy at the outbreak of the Civil War, serving as a captain’s clerk on blockade duty of the Confederacy’s South Atlantic coast. He kept on painting, though, and attracted the attention (and patronage) of the blockade squadron’s commander, Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, and in the post-war years began painting scenes of Civil War naval battles, including seven versions of the fight between the Alabama and Kearsarge, Final Assault on Fort Fisher (1872), Sinking of the Cumberland (1872), and Rebel Ram “Tennessee” Attacking U.S. Ships Richmond and Lackawanna (1873). These earned him such great popularity that when the U.S. government undertook the massive project of publishing The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in 1895, eight of Smith’s sketches were used as illustrations for the series. In his later years, Smith advertised himself as the “oldest living and practicing artist with Civil War experiences, and turned to painting scenes of Civil War land battles, painting Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg (1913) and John Burns at Gettysburg (1915).[8]

In addition to the Schweizer statue, the League also owns eight busts of Abraham Lincoln, and a small-scale standing statue of Lincoln created by Daniel Chester French (who also sculpted the sitting Lincoln which is the centerpiece of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington). The statue was the offspring of the Abraham Lincoln Centennial Memorial Association, which had been formed in 1908 by the Nebraska state legislature to create a “state and memorial” to Lincoln and was funded by state appropriations and popular fund-raising. French originally created an eight-foot outdoor bronze statue of Lincoln for the Association, to be sited on the grounds of the Nebraska state capitol, showing Lincoln at Gettysburg. It is a contemplative Lincoln, with his head inclined downwards and his hands clasped in front of him, as if Lincoln was “bearing the burdens and perplexities and problems of the Great War.” A granite wall behind the statue carries the words of the Gettysburg Address. At the dedication ceremonies on September 2, 1912, the featured speaker was William Jennings Bryan, the “Silver-Tongued Orator of the West” and three-time presidential candidate. Like many sculptors, French hoped to make money from selling smaller, domestic versions of the statue. One full-sized plaster copy went to the Art Institute of Chicago, another to San Francisco, while bronze statuettes were offered for sale for $1000. The association which had commissioned the Nebraska statue objected to marketing the statuettes, and in the end, only twelve of the statuettes were made (one of them being acquired by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney for the museum of American art she was creating in New York City).[9]

Of the League’s Lincoln busts, the most striking is a 17-inch-high figure, cast in bronze in 1880 by Leonard Wells Volk (1828-1895). Born in New York but working as a sculptor in Chicago, Volk first met Lincoln during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858, where he gained a promise from Lincoln to give the Rome-educated sculptor a sitting. In the spring of 1860, reading in the Chicago papers that Lincoln was in the city on legal business, Volk collected on the promise. The sitting was a novelty for Lincoln. “Mr. Volk, I have never sat before to sculptor or painter—only for daguerreotypes and photographs. What shall I do?” Volk made a plaster cast of Lincoln’s face, which Lincoln had a “pretty hard” time working off, and then had Lincoln sit while he made preliminary shapings of his head. Volk had in mind creating a ‘Hermes bust’—“to represent his breast and brawny shoulders as nature presented them”—and in May, Volk finished a “cabinet-size” version to present to Lincoln in Springfield. But by that time, Lincoln had been nominated for the presidency, and Volk embarked on a series of versions of the bust, some in classical drapery, some just from the neck-up (the League’s copy is one of the latter). Volk also took an additional plaster cast of Lincoln’s right hand in expectation of creating a full-size statue. The statue did not materialize until 1876, for the Illinois state capitol, but the busts became one of the most popular three-dimensional images of Lincoln.[10]

Another bust, this time in marble, was created by Pio Fedi (1815-1892) in 1865, drawing upon photographs and prints. Fedi, who worked in Florence, specialized in highly stylized renderings of figures from Italian history, and his full-scale statue of General Manfredo Fanti (one of the principal military leaders in the wars for Italian independence and unification) still dominates the Piazza San Marco in Florence. Fedi’s bust of Lincoln is, unhappily, much more bland than the dramatic Fanti statue: it is a fully-bearded Lincoln, in coat, vest and bow-tie, and gives Lincoln a slightly fierce, almost irritated expression. At the other extreme from Fedi is the more recent marble bust created by Raymond Granville Barger (1906-2001). Barger’s bust is reminiscent of the 40-inch bust made by Gutzon Borglum in 1908, which seems to show Lincoln’s head emerging from the Alabama marble Borglum used as his material. Barger’s 31-inch bust also features Lincoln’s head, half formed from the sculptor’s marble, and like Borglum’s bust, imparts to Lincoln a certain dreaminess. Curiously, Barger originally cast his bust in bronze in 1937 to commemorate Lincoln’s correspondence with the tiny Republic of San Marino in 1861, when Lincoln thanked the “Regent Captains” of San Marino for their support of the Union. Like the American republic, San Marino had “demonstrated the truth, so full of encouragement to the friends of Humanity, that Government founded on Republican principles is capable of being so administered as to be secure and enduring.”[11] The marble version was presented to the League in 1991, with the 85-year-old artist in attendance.

The most unusual bust in the collection was created by Agnes Yarnall (1904-1989), a Philadelphia-based sculptor who created a series of forty-two bronze busts of Civil War figures to illustrate a book of her poetry in 1980, An Attempted Evocation of the Civil War: Sculpture and Poetry.[12] The 21-inch-high head of Lincoln in this series is rough-cast and beardless, from mid-chest upward, with an enigmatic and distant expression. Probably the least unusual, or at least the most expressionless, of the League’s Lincoln busts, Abraham Lincoln, was cast in bronze in 1993 by Zenos Frudakis (1951- ), who specializes in monumental sculptures of celebrities, from Winston Churchill to Don McLean. (A far more idiosyncratic and sharply-detailed Lincoln bust by Frudakis, Old Abe, at the Cornell University Library, shows an inquisitive Lincoln, head cocked at a slight angle, eyebrows slightly arched, as if puzzled by something.)[13] One final bust is a copy of the head of the famous Augustus Saint-Gaudens Standing Lincoln in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, awarded to Russell F. Weigley in 1991 as part of the annual presentation of the Lincoln Prize in 2001.

Some of the busts are actually smaller-scale reductions of larger statues. Max Bachman (1862-1921) created two seven-foot Lincoln statues (one beardless and the other bearded, but in the same pose) modelled roughly upon the Saint-Gaudens Standing Lincoln. Bachman was born in Germany, educated in Berlin, and emigrated to the United States in 1885. While his most dramatic works were the allegorical figures that adorned the New York World building, his Lincoln statues were hailed as “the finest likeness of Lincoln ever produced in sculpture.” As well they might be, since they are really nothing more than the Saint-Gaudens and with a slightly re-modeled head (beardless and otherwise). The League’s bust version is a sharply-rendered portrayal of the beardless Lincoln, twenty-seven inches high and showing Lincoln from mid-chest upwards. A bearded version of the bust, presiding over the Urbana (Illinois) Public Library, has been described by Orville Vernon Burton as “searching the distant future and hoping for a land of equal rights and equal opportunity as proposed in his beloved Declaration of Independence” with “a strength of character, a powerful, almost austere, authority.”[14]

In the same way, George Edwin Bissell (1839-1920), a Union veteran, created a full-length statue of Lincoln on commission in 1893 from Wallace Bruce of Edinburgh for his city’s Old Calton Burial Ground. It commemorates the “Scottish-American Soldiers” of the Civil War, and shows Lincoln standing in a reflective pose, his left arm drawn behind him and his right extended downwards, with his right hand holding a document intended to be the Emancipation Proclamation. A copy of the statue was commissioned by Iowa Governor William Larrabee in 1902 for his hometown of Clermont, and (like French and Bachman) Bissell marketed statuette and bust versions.[15] Another statuette, possibly the creation of the French sculptor Auguste-Joseph Peiffer (1832-1886), shows Lincoln standing beside a short obelisk, his left hand resting on two books and a scroll with the words Abol Slavery. Peiffer was mostly known for his bronze sculptures on classical themes—Diana the Huntress, The Wise Virgin, A Classical Couple – rather than historical figures, and no other copy of a Peiffer Lincoln seems to exist. (The League’s copy was purchased in the Faubourg St. Honore in Paris; otherwise nothing is known about its provenance.)

Finally, there are in the League’s collections six medallions featuring Lincoln at half-face, the most impressive being one of a series made in 1865 by Franklin Simmons (1839-1913) in copper and bronze of thirty-one of the most prominent Union generals. (Lincoln, along with William Henry Seward, John Usher, Gideon Welles, James Speed, and Salmon Chase, are the only civilian leaders in the series.) The medallions were “modeled in clay from life sittings” by Simmons, and originally exhibited in the fall of 1865 at a fund-raising fair for the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home (alongside Xanthus Smith’s Lincoln portrait and Thomas Sully’s Washington). The medallion series, cast by the William Miller Foundry of Rhode Island, was purchased by the League; in 1869, the League purchased another Miller medallion, Triumviri Americani, depicting the heads of Washington, Lincoln, and Ulysses Grant superimposed in series on each other.[16] Another medallion, in bronze, by outdoor sculptor Jonathan Scott Hartley (1845-1912), depicts a beardless Lincoln, surrounded by a laurel wreath.[17] There are also painted-plaster copies of the life masks made of Lincoln by Leonard Wells Volk in 1860 and by Clark Mills (1815-1883), who executed the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson across from the White House, and who made his mask of Lincoln in February, 1865.[18]

Abraham Lincoln has been one of the most popular subjects for American artists, and many institutions display Lincoln portraits as prime exhibits from their collections—the Walter Travers portrait at The Brook and Emmanuel Leutze’s Abraham Lincoln (1865) at the Union League Club, both in New York City. Outdoor statues of Lincoln range from Gutzon Borglum’s great face on Mt. Rushmore to Otto Schweizer’s 1913 Lincoln statue for the Pennsylvania Monument on the Gettysburg battlefield. One Lincoln statue, by George Grey Barnard, even triggered an international incident in 1919, when Robert Todd Lincoln objected to its installation across from Parliament Square. (The statue was eventually relocated to Manchester, and given the close support Lincoln received from Manchester during the Civil War, there was actually something appropriate in the re-location.)[19] But the Union League of Philadelphia’s Lincoln collection is unique for its variety and range, and especially for the great Marchant portrait.

Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University. He would like to acknowledge the help of James Mundy and Keeley Tulio of the Union League for their help in this article.

[1]Nicholas Wainwright, “The Loyal Opposition in Civil War Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 88 (July 1964), 298.

[2]George Parsons Lathrop, History of the Union League of Philadelphia, from Its Origin and Foundation to the Year 1882 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1884), 37; O.H. Leigh, Chronicle of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1902), 129-30.

[3]John W. Forney to Lincoln (December 30, 1862), in Dear Mr. Lincoln: Letters to the President, ed. H. Holzer (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1993), 85.

[4]Harold Holzer, Gabor Boritt & Mark E. Neely, The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1984), 10

[5]Barry Schwartz, “Picturing Lincoln,” in Picturing History: American Painting 1770-1930, ed. William Ayres (New York: Rizzoli, 1993),138; Union League of Philadelphia Heritage Center – https://ulheritagecenter.pastperfectonline.com/Webobject/F6F25794-6809-4153-91D0-373258947400.

[6]Marchant, in Andrew L. Thomas, “Edward Dalton Marchant’s Abraham Lincoln,” in Philadelphia’s Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy, eds. Katharine Martinez & Page Talbott (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 65.

[7]Ernst Jockers, J. Otto Schweizer: The Man and His Work (Philadelphia, PA: International Printing, 1953), 53-55; Maxwell Whiteman, Gentlemen in Crisis: The First Century of the Union League of Philadelphia, 1862-1962 (Philadelphia, PA, 1975), 213-17.

[8]Robert Wilson Torchia, Xanthus Smith and the Civil War (Philadelphia: Robt. Schwarz, 1997), 1-7.

[9]“Lincoln Monument,” Public Documents of Nebraska, 1911-1912 (Lincoln, NE: M.E. Logan Bindery, 1913), 1:8-17; Harold Holzer, Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2019), 224-31.

[10]“Leonard Wells Volk,” in Mark E. Neely, The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia (New York: McGraw Hill, 1982), 319-20; Volk, in Francis Fisher Browne, The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln: A Narrative and Descriptive Biography with Pen-Pictures and Personal Recollections by Those Who Knew Him (Chicago: Browne & Howell, 1913), 237-42; Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 241.

[11]Lincoln, “To the Regent Captains of the Republic of San Marino” (May 7, 1861), in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. R.P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4:360.

[12]“Agnes Yarnall LePage of Ardmore, known for her sculpture, also a poet,” Philadelphia Inquirer (June 8, 1989).

[13]“Old Abe” — https://www.zenosfrudakis.com/sculpture/old-abe.

[14]Pietro P. Caproni, Catalogue of Plaster Reproductions from Antique, Medieval and Modern (Boston, MA, 1911), 40; Darold Leigh Henson, “Max Bachman’s Lincolns” — chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://findinglincolnillinois.com/abestatueplan/BachmansLincolns12-12.pdf; Richard E. Hart, ed., Lincoln in Illinois (Springfield, IL: Abraham Lincoln Association, 2009), 101-2; Donald Charles Durman, He Belongs to the Ages: The Statues of Abraham Lincoln (Ann Arbor, MIL Edwards Bros., 1951), 203.

[15]Durman, He Belongs to the Ages, 65-66.

[16]“The Patriotic Fair,” Philadelphia Inquirer (October 28, 1865).

[17]“Jonathan S. Hartley Dead,” New York Sun (December 7, 1912).

[18]Harold Holzer & Loyd Ostendorf, “Sculptures of Abraham Lincoln from Life,” Antiques 113 (February 1978), 389; Ostendorf, “A Relic from His Last Birthday: The Mills Life Mask of Lincoln,” Lincoln Herald (Fall 1973), 79-85.

[19]Frederick C. Moffatt, Errant Bronzes: George Grey Barnard’s Statues of Abraham Lincoln (Newark, DE, 1998), 173-5; Terry Wyke, Public Sculpture of Manchester (Liverpool, 2004), 90-91; Robert Todd Lincoln to Isaac Markens (August 28, September 7, and October 2, 1917), in A Portrait of Abraham Lincoln in Letters By His Oldest Son, ed. Paul M. Angle (Chicago, 1968), 41, 42, 44; James A. Percoco, Summers With Lincoln: Looking for the Man in the Monuments (New York, 2008), 75, 115-16.