Lincoln the Inquirer: An Interview with M. Kelly Tillery, Esq

Lincoln the Inquirer: An Interview with M. Kelly Tillery, Esq

Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Please explain your conclusion that Abraham Lincoln was inquisitive at an early age.

M. Kelly Tillery: A number of people who knew Lincoln as a boy and young man remarked on his voracious appetite for information about anything and everything. Herndon’s “informants” are particularly instructive in this regard. For example, his cousin, Dennis Hanks, thought Lincoln as a boy “sometimes uncomfortably inquisitive” as when he would often be the first to ask questions of passing strangers. Like the few books he could get his hands on in frontier Indiana, then Illinois, sojourners bearing news, innovations, and fresh ideas were a window to the world for a wide-eyed, already ambitious young man in the West. Lincoln would assiduously milk each volume as he would each visitor for every drop of knowledge.

Evidence of his early thirst for knowledge and questioning can be found in the recollections of Herndon’s 250 “informants,” the Fehrenbacher’s 529 “recollectors,” and, to some extent, in the compilations of Allen Thorndike Rice’s 32 “distinguished men” and John G. Nicolay’s 39 “interviewees.” There is, of course, no substitute for getting to know Lincoln and his passion for inquiry, than to read and reread the Collected Works and the accounts of those who actually knew him, even if the latter were often somewhat tainted by self-interest and time.

SG: Your research shows that Lincoln used the word “question” over 1,300 times in speaking and writing. How and why did he use this word?

MKT: Lincoln used the word in at least four respects 1) as an issue or problem at hand in a case or politics, 2) as an interrogatory posed to him or by him to his opponent, the public and sometimes posterity, 3) as a challenge to an opponent regarding the veracity or basis of a claim, and 4) as a rhetorical device. Most often he used it to identify a particular, perplexing issue of public import. Then, like a good lawyer, he would explain it, address his position on it, state his opponent’s position (often better than his opponent), and then eviscerate his opponent’s opinion with “cold, calculating unimpassioned reason.”

SG: What was the effect of the Age of Reason on Lincoln’s thought process?

MKT: For Lincoln, evidence and reason were as important as morality. The Enlightenment had revived interest in and reverence for these complementary concepts, including the Socratic Method of questioning, and put aside reliance on faith, authority, and tradition for conclusions. This made perfect sense to Lincoln’s logical mind and is evident in his earliest public pronouncements such as the 1832 Handbill promoting his first Illinois legislative candidacy and his 1838 Lyceum Address. He eschewed faith; argument from authority and tradition; mysticism or anything other than actual, verifiable evidence and logic. Lincoln was always curious about how things worked – devices, natural phenomena, people and institutions.

Only the tools of Socrates, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution could lead him to answers that worked. Like a scientist, he kept an open mind and was prepared to be proven wrong by the very process he cherished and to admit so. Lincoln sometimes did his own prodigious historical and legal research, as he did for his Peoria and Cooper Union speeches, but he did not question any “expert” professional historians until he become President when he asked the pre-eminent historian of the time, George Bancroft, for historical information on the presidency.

SG: As an attorney yourself, I am interested in how you believe that Lincoln’s ability to pose questions aided him in his legal career?

MKT: The heart of any successful trial is the ability to develop a theme and ask the right questions of (1) your own client, (2) your opponent, and (3) any independent witnesses. Then, and only then, can you ask the key questions about what Lincoln called “the nub” (sometimes “nub” or “pith”) of the case. Every case has one and Lincoln was a master at separating the wheat from the chaff to find and elucidate it.

SG: You use Lincoln’s response to President Polk’s support for the Mexican War as indicative of his ability to ask questions in order to prove a point. Please explain.

MKT: When Lincoln first went to Washington in 1847, he brought with him the interrogation skills he had honed in a decade of trials in scores of dusty courtrooms throughout the Prairie State. As a cheeky freshman Congressman, Lincoln introduced a series of resolutions critical of President Polk’s Mexican War. Eight of those were specific interrogatories directed to the President himself focusing on the “spot” where the military action had allegedly begun. Known derisively as the “Spot Resolutions,” only three actually asked about “spots.” Polk ignored Lincoln and never answered his questions.

In a classic, succinct, simple inquiry, Congressman Lincoln pressed President Polk to answer:

“Now sir, for the purpose of obtaining the very best evidence… “let the President ask those interrogatories.” “Let him answer, fully, frankly and candidly.” “Let him answer with facts, not with arguments. If he can show that the soil was sour, where the first blood of the man was shed. In that case, I shall be most happy to reverse the vote I gave the other.” Lincoln’s unanswered questions still had some positive effect as the House of Representatives informally censured Polk for doing precisely what Lincoln had charged.

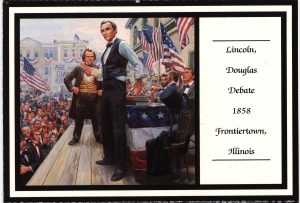

SG: How did Lincoln use questions to his advantage during his debates with Stephen Douglas?

MKT: By 1858 Lincoln had honed his talent for precise questioning to a razor’s edge, and used his inquisitive scalpel to slice and dice his longtime nemesis Stephen A. Douglas in their seven debates.

“Judge” Douglas actually initiated this inquisitorial gambit when he, perhaps in retrospect unwisely, posed seven such questions to Lincoln at their first debate at Ottawa, Illinois, on August 21, 1858. Six days later at Freeport, Illinois, Lincoln deftly responded to those “seven distinct interrogatories” and propounded four of his own back to the Judge. For Douglas’s convenience but more for dramatic effect, Lincoln left a written list of his “historic four” on the podium for Douglas. Both would go on to address those key total of eleven questions, all regarding the question of the day – expansion of slavery, at their following five debates.

Herndon reports that Lincoln’s second reply interrogatory to be propounded to Douglas at Freeport, “Can the people of a United States Territory, in any lawful way, against the wish of any citizen of the United States, exclude slavery from its limits prior to the formation of a State Constitution?” was the subject of “The Dixon Conference.” At Dixon, Illinois, Lincoln was counselled by his Chicago friends, Norman B. Judd and Dr. C.H. Ray, (Editor of the Tribune) not to ask Douglas that question as he would say, “yes” and ensure his re-election. Lincoln wanted an affirmative response, knowing it would destroy Douglas’ hope for votes in the South in the 1860 Presidential election. Douglas did answer “yes” and this, his “Freeport Doctrine,” did doom him in the South, leading to Lincoln’s election.

SG: Please give an example of President Lincoln’s use of questions to Cabinet members.

MKT: The Constitution, specifically authorizes the President to “… require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices.” (Article II, Section 2 (1.2)

Although he often asked his Cabinet for advice via a posed question, and often acted as their majority opined, he always made it clear that he was asking for information and reasoning and that he alone would decide the question, upon consideration of their responses.

In a speech in the House of Representatives, on July 27, 1848, Lincoln had foreshadowed his use of pointed questions to his own Cabinet a dozen years later, when he approvingly spoke of George Washington’s inquiry of his cabinet for written opinions on the constitutionality of a bill chartering the First Bank of the United States. The Constitution, of course, specifically authorizes the President to “… require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices.”

It did not take Lincoln long to use this constitutional tool for subjects both general and specific to departments with his own “team of rivals.” Just seven days after his inauguration, on March 11, 1861, with Forts Sumter and Pickens under siege by Confederate troops, Lincoln posed his first formal question, a hypothetical, to his Cabinet members requesting written responses: “Assuming it to be possible to now provision Fort-Sumpter, [sic], under all circumstances, is it wise to attempt it?” A simple “yes,” or “no” question, but Secretaries Seward, Bates, Welles, Cameron, Chase, Smith and Blair (all but Cameron – legally trained themselves) each gave more loquacious answers. Only Blair answered “yes,” to both without conditions. As he almost always did, Lincoln followed his initial instinct rejecting his Cabinet’s majority conservative position.

It did not take Lincoln long to use this constitutional tool for subjects both general and specific to departments with his own “team of rivals.” Just seven days after his inauguration, on March 11, 1861, with Forts Sumter and Pickens under siege by Confederate troops, Lincoln posed his first formal question, a hypothetical, to his Cabinet members requesting written responses: “Assuming it to be possible to now provision Fort-Sumpter, [sic], under all circumstances, is it wise to attempt it?” A simple “yes,” or “no” question, but Secretaries Seward, Bates, Welles, Cameron, Chase, Smith and Blair (all but Cameron – legally trained themselves) each gave more loquacious answers. Only Blair answered “yes,” to both without conditions. As he almost always did, Lincoln followed his initial instinct rejecting his Cabinet’s majority conservative position.

Over the next four years, Lincoln posed many such important questions to his Cabinet members collectively, but as often did so individually where their particular department’s interest or expertise was involved.

SG: Did President Lincoln use his skills in interrogation with military leaders, or was he more inclined to issue direct orders?

MKT: Lincoln rarely issued direct orders to his military leaders, except when frustrated by inaction and/or manifest error. Aware that he had little military experience or knowledge, Lincoln did in this realm what he did in all others – he questioned the experts and he read the books. However, he had little time or interest in reading detailed military or other reports. His ability to focus on the “nub” of the case and to ask only a few, but the right, questions was uncanny. Two days before even his first questions to his Cabinet, on March 9, 1861, Lincoln submitted three equally pointed and numbered interrogatories to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott regarding Fort Sumter’s ability to endure and Scott’s ability to resupply it. Scott’s unencouraging responses left Lincoln unsatisfied, but also undaunted.

On several occasions, in lawyer-like fashion, Lincoln posed simple, clear interrogatories to his generals, sometimes in list format numbering as many as 34 at a time, as in his famous “Harrison’s Landing Questions” in July 1862 to 12 of his generals, including McClellan.

Lincoln’s withering inquiries could not easily be evaded. And those who tried seldom fared well. Lincoln’s legal colleague, Isaac Arnold, said, “In the examination and cross-examination of a witness he had no equal. He could compel a witness to tell the truth when he meant to lie, and if the witness lied, he rarely escaped exposure under Lincoln’s cross-examination.”

SG: What was Lincoln’s “naked question?”

MKT: Although “naked” was one of his favorite adjectives, for Lincoln, the “naked question” was the extension of slavery. It was the question which lit the fuse which exploded into civil war and the question to which he was called or driven to answer to the nation and posterity. All else – his political career, his election, his presidency, saving the Union, war and peace, ending slavery, assassination, and Reconstruction flowed from this one, “naked question.” For Lincoln, it was “the nub” of the case.

Kelly Tillery practices law in Philadelphia, PA