Lincoln & the Franchise

Lincoln & the Franchise

M. Kelly Tillery, Esq.

“The most fundamental right in America is the right to vote—and to have it counted. And it’s under assault. In state after state, new laws have been passed, not only to suppress the vote, but to subvert entire elections. We cannot let this happen.”

Joseph R. Biden, Jr., 46th President of the United States of America, State of the Union, March 1, 2022

Teddy Roosevelt, who at six years old, on April 25, 1865, watched Lincoln’s funeral procession from a window of his grandfather’s home in Manhattan, often said that as president, when confronted with a dilemma, his first inquiry to himself was, “What would Lincoln have done?”

As we today face an unprecedented, relentless, well-organized, systematic, nationwide effort to suppress, dilute, not count, and even change the votes of millions, surely it is timely to ask, “What would Lincoln do?” To answer, we must examine what he said and did in regard to the sacred franchise. Lincoln dealt with virtually every electoral issue we encounter today – fraud claims without evidence, actual fraud, voter ID, alien voters, voter eligibility restrictions, military vote, gerrymandering, sore losers, conspiracy theories, bundling, drop boxes, mail-in voting, recounts, court challenges, court-packing, and more.

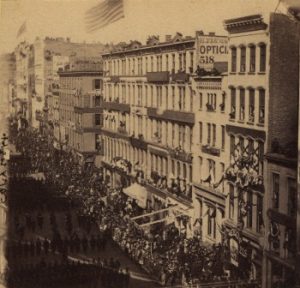

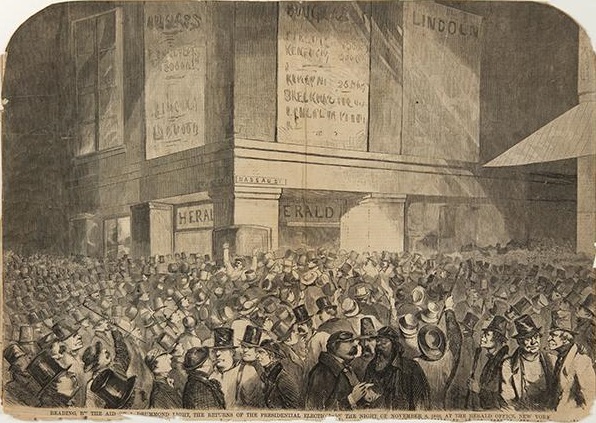

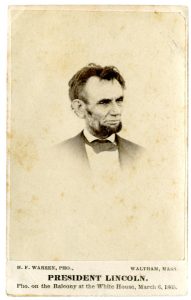

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected to the presidency in a nation of 31,443,321 people, the largest democracy then or ever to that point. The United States was the only large democracy other than Britain, though that nation restricted the franchise to less than 3 percent of its citizenry and had an unelected, hereditary monarch and one unelected, hereditary legislative house. The Swiss Republic, the Republic of San Marino, Liberia and the Boer Republic were the only other democracies in a world otherwise governed by a variety of dictators, warlords, and “royals.” As historian Michael Lind says, the United States was “the first-sustained, large-scale republic since antiquity.” This nation and its special form of government, “of the people, by the people and for the people,” was then only four score and four years young. It was still an experiment and, sadly, in serious danger of failing because 11 of 33 states that had participated in a free and fair national election refused to accept its outcome – the greatest single voter suppression event in history.

Over a period of 34 years Lincoln had actual experience at every level of the electoral process, from the most basic casting his first ballot to the pinnacle of being re-elected president. He served as voter, election clerk, vote tally courier, candidate, state legislator, congressman, presidential elector, campaign manager, and president. Along the way, he was also employed in areas intimately intertwined with electoral politics, including postmaster, journalist, essayist, lecturer, newspaper owner, and, of course, lawyer. And, curiously, he was a victim of voter suppression himself on more than one occasion.

FIRST CONTACT

The earliest election-related document in Lincoln’s hand is a May 26, 1830, Petition to the Macon County Commissioners’ Court signed by Lincoln and 44 other “qualified voters” requesting that the polling location for Decatur Precinct be moved from Permenius Smallwoods to the courthouse in Decatur. Curiously, although not yet then actually such a “qualified voter” due to the Illinois six-month residence requirement and not yet even aspiring to be a lawyer, it is an example of the early recognition by his neighbors that he could write and of his civic engagement in the electoral process. He was all of 21 and had been in Illinois only a couple of months. The petition states no reason for the request or the location, apparently a man’s name and no doubt referring to his home, but the Decatur Courthouse on the southwest side of the new town square was a central location and would make voting easier for most of the small electorate.

Thus, even before he cast his first vote, Lincoln publicly expressed concern and demand for making voting easier for more people. It became a recurring theme in his political life. Ironically, however, the man soon to be called “Honest Abe” began his political journey disenfranchised by voter eligibility limits and with a technically false written representation to a government body.

GERRYMANDERING

Lincoln jumped into the partisan politics of reapportionment in a special section of the Illinois legislature early in his political career in December 1835, just as he was becoming one of the Whig floor leaders. The “Long Nine” of Sangamon County, including the longest, Lincoln, were a product of that 1835 reapportionment. Thus, Lincoln and the interests of his constituents were beneficiaries of partisan apportionment, though, of course, not then (yet) based on race or any other immutable characteristic, just political party.

By the early 1850s the tables were turning and though the Democrats held control, they required gerrymandering to maintain power. Lincoln litigated only one significant case related to the franchise and it involved reapportionment. In People ex rel Lanphier and Walker v. Hatch, 19 Ill. 283 (1857), he successfully prevented Democrat legislators from compelling the implementation of a gerrymandered reapportionment bill.[1] In 1857, Illinois was a microcosm of the divided nation – a Republican governor with a Democrat-controlled House and Senate, based on Republican majority in the north and Democrat majority in the south. But things were changing. As Chicago and the north expanded, Republicans were swamping Democrats and would surely lead in the 1858 elections in a fair vote – unless the Democrat-controlled legislature somehow changed the rules so that their newly-minoritized party could retain control.

As the Illinois Constitution of 1848 required reapportionment every five years, a new legislative district map was required in 1857 based on the 1855 census. Since the days of Elbridge Thomas Gerry (1744–1814) and his infamous “Gerry-mander”[2] (1812), manipulation of legislative district shapes had been a time-worn, sure-fire way for a minority to cling to power by changing the rules. The Illinois Democrats moved swiftly to pass a reapportionment bill proposed by Representative Samuel W. Moulton (D-Shelbyville) on strict party lines in the House (38 to 33) and the Senate (13 to 9).

All, including Lincoln, expected the Republican governor, William H. Bissell, to veto this obvious partisan ploy, but being handed several bills at once to act upon by his private secretary, Benjamin F. Johnson, Bissell “inadvertently” signed the reapportionment bill and Johnson reported the same to the House. Bissell quickly realized his error, crossed out his signature, inserted “Not” before “Approved” and sent a veto message half an hour later on February 18, 1857.

While most would have understood this simple human error and accepted the correction, desperate Democrats refused to let go of this slender thread of gimmickry that just might allow them to retain power, albeit soon a minority.

One can imagine Lincoln simply whittling, shaking his head, thinking, “This is why people hate politicians.”

The parties lawyered up and girded their loins for battle in the Illinois Supreme Court over one word – “not.” Republican Lincoln represented Secretary of State Ozias M. Hatch while Lincoln friend and frequent political and legal opponent Democrat John A. McClernand represented Lanphier and Walker, printers. Though the printer-plaintiffs nominally sought a mandamus (court order) directing Hatch to give them the “approved” apportionment bill to publish “as the law,” the case was actually simply a test of the validity of Governor Bissell’s correction of his mistake.

Lincoln and his co-counsel, fellow Republican Jackson Grimshaw, opposed the Democratic petition for mandamus. After briefing and three hours of argument, the three Democratic members of the Illinois Supreme Court, eschewing party loyalty and applying common sense and reason, denied the petition, allowing the veto to stand. Lincoln had defeated the Democrats’ effort to change the rules to avoid the effect of a change in the composition of the electorate.

While a victory for principle, law, and Lincoln, the practical implications for him were not so. Without any new reapportionment at all, the 1858 legislature was elected based on the 1854 apportionment, which also favored the Democrats as based on the then outdated 1850 census. That new legislature, also Democrat-controlled, unsurprisingly tried again to gerrymander the districts. Incensed that they would disregard the spirit of the Illinois Constitution and to try to continue control by “a minority of the people,” Lincoln himself authored Governor Bissell’s second and timely veto message. To add insult to injury, that same Democrat-controlled legislature sent Stephen A. Douglas back to the U.S. Senate instead of Lincoln, even though there were more Republican votes than Democrat for the state legislators who made that choice. Lincoln was defeated, victim of a gerrymander.

Lincoln and friends, however, had the last laugh. Even under the 1854 “Democrat-favored” apportionment, Republican majorities were elected in both houses and reapportioned districts more fairly in 1861 based upon the U.S. Census of 1860. And, of course, by then Lincoln was elected president and had on his hands a much larger abuse of the electoral system by eleven Southern states.

CLAIMS OF VOTER FRAUD

Lincoln’s first known encounter with claims of voter fraud was in the 1838 Illinois congressional election in which his then-law partner, Whig John Todd Stuart, bested Lincoln’s lifelong political nemesis, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, by only 36 votes out of 36,000 – 1/10 of 1 percent. Douglas charged fraud and demanded Stuart agree to a new election, but Stuart demurred. Lincoln sprung to his colleague’s defense. Ever the advocate, Lincoln knew that “the best defense is a good offense” and that evidence of improper votes for Douglas would be good ammunition in any upcoming legal fight.

Lincoln signed, sent and probably drafted a letter to the editor of the Chicago American newspaper, William Stuart, (and also to other friendly Whig editors) requesting assistance in “the collection of proofs” regarding whether there were any mistakes “for or against Mr. Stuart” “on the face of the Poll Books of your County?, whether any minors or persons not resident for six preceding months had voted, and whether any ‘unnaturalized foreigners’ had voted for Douglas?”

Lincoln went further, asking for the “names” of any such “illegal voters,” the names of any witnesses regarding same and the names of local justices of the peace before who depositions could be taken to “procure the proofs.” And finally, Lincoln urged the editors to “consult political friends,” “solicit their assistance in procuring the above facts,” and appoint “precinct committees as you may think advisable.”

This aggressive, political, and legal effort to gather evidence useful in any court challenge is classic Lincoln – assess the injustice, gather all the evidence, ensure it is legally proper and admissible and be fully prepared for challenge. It is safe to assume that Douglas became aware of this early, bold, and preemptive move by Lincoln and it may have been the, or one of the, reasons he decided not to challenge Stuart’s election. Like many defeated candidates and their supporters, Douglas may have felt cheated and sincerely believed that there was impropriety in the process, but actual evidence, and evidence of wrongdoing without which he would have won, was required to overturn an election. Douglas was a politician but he was also an able lawyer, a litigator, and knew the challenger had the burden under law to prove fraud sufficient to change the results. As much bluster as there was, there was just as little evidence – an all too common theme in election fraud cases.

Only two years later, Lincoln faced more such baseless claims. Whig William Henry Harrison defeated incumbent Democrat President Martin Van Buren in 1840 by a wide electoral margin. While the popular vote was close, there were no claims of widespread voter fraud at the national level. However, in Illinois, some disgruntled Democrats did make serious allegations of massive fraud, though more in concern for local elections with closer margins.

As he had just done the year before, Lincoln bristled at the suggestion that the sacred franchise had somehow been infected by fraud and spoke up with power and conviction. Lincoln friend, colleague at the bar, and frequent political opponent, John A. McClernand, Democrat of Gallatin County, complained of several instances of fraud including a claim about a mysterious steamboat which had allegedly plied the waters of the Wabash River up and down “voting a large number of people in various towns.”

Lincoln remarked on these baseless claims in the House and proactively introduced a resolution to have the matter “referred to the committee on elections” “to prepare and report” “a Bill [to] … afford the greatest possible protection of the elective franchise, against all frauds of all sorts whatever.” Lincoln was thus on record against “all frauds” and for the “greatest possible protection of the elective franchise,” but he was also requiring actual evidence of the same.

In response to “the Governor’s Message as it relates to fraudulent voting” and McClernand’s rantings, Lincoln called these claims “stupendous frauds,” “without granting for a moment the truth of any of the gentleman’s charges and surmises.” While he was “afraid of no investigation” and “if it was a fact that Legislative action was necessary to protect the elective franchise from abuse,” he could see no good coming from the investigation McClernand proposed because “he had every reason to believe all this hue and cry about frauds, was entirely groundless and raised for other than honest purposes.”

In order to test “the truth and character of these charges” Lincoln brazenly offered his own Sangamon County as a test case of a “special investigation” wherein “every vote should be scrutinized.” He observed that, “as much fraud had been charged to have taken place in Sangamon County as anywhere else,” “surely no gentleman who was honest in his beliefs of these frauds could object to the proposition.”

Lincoln thus made clear that there was no evidence of fraud, that the “hue and cry” was “raised for other than honest purposes” and a simple test in a sample county would likely confirm the same. Ever the careful lawyer, he demanded actual evidence, not political bluster. Unsurprisingly, again, no such evidence was ever forthcoming and the dispute died on the vine.

“ERIN GO VOTE…”

On October 20, 1858, Lincoln expressed concern about large scale voter fraud by Democrats in “doubtful districts” using Irish railroad workers to vote where they did not reside. Based only upon his “meeting” of “fifteen Celtic gentlemen, with black carpet sacks in their hands” in Naples, Illinois, and a rumor he heard in Brown County about 400 such men being “brought into Schuyler, before the election,” Lincoln wrote to his colleague Norman B. Judd, that what he feared was Democrats taking advantage of an electoral loophole and of such men by having them vote in a district where they did not reside. Lincoln knew that as they were “legal voters in all respects except residence” all they had to do was “swear to residence” and that would “put it beyond our power to exclude them.” He knew it would be “next to impossible to convict them of perjury upon it.”

Lincoln may have been paranoid on this point as he had little, if any, evidence of such a widespread, elaborate conspiracy. But his concern must have been genuine, as he told Judd twice that he was confident of winning, “if we are not over-run with fraudulent votes to a greater extent than usual” and “if we can head off the fraudulent votes,” and then, oddly, he “suggested” a “dirty trick” of his own.

To counter this anticipated voter fraud by his opponents, in a very un-Lincolnlike manner, he made to Judd a “bare suggestion” that was arguably unethical and possibly illegal. It must be noted that this scheme pre-supposed that there was, in fact, such “a known body of these [illegal] voters,” as Lincoln began his “suggestion” with, “Where there is a known body of these voters…” Apparently feeling “turnabout is fair play,” Lincoln thought it would be “a great thing,” “when the trick is attempted on us,” to have “a true man of a ‘detective’ class” “introduced among them in disguise” “who could at the nick of time, control their votes?” presumably meaning to have them vote (illegally) Republican, not Democrat. “Think it over. It would be a great thing, when this trick is attempted, to have the saddle come upon the other horse.”

So, not only was Lincoln suggesting that they suborn perjury (have voters attest falsely on residence), but also that they encourage widespread voter fraud and interfere with a man’s sacred franchise. If he was also intimating that they be bribed to vote Republican, then he was “suggesting” at least four or five crimes per voter. Not exactly “Honest” Abe.

Fortunately, the hordes of perjurious Celts were not to be found on election day and Lincoln’s “bare suggestion” remained just that, not evidence cited in his indictment.

ACTUAL VOTER FRAUD

Lincoln’s concern with voter fraud on occasion was real and documented, but evidence of actual voter fraud, much less any conviction for the same, was extremely rare. In fact, there is only one known instance of convictions for voter fraud of which there is evidence that Lincoln was aware.

On February 27, 1865, five days before his Second Inaugural and three months after his re-election, Lincoln wrote to Judge Advocate General of the U.S. Army Joseph Holt asking him to “procure the record, and report to me, on the case of Edward Donahue, Jr. about election fraud.” Lincoln was assassinated only six weeks later, so we know not why he wanted this information, whether he received it or what he intended, if anything, to do about it.

Donahue had defended the charges against him of forging ballots for soldiers but had been convicted in large part based on the confession and testimony of his cohort, Moses J. Ferry. Donahue and Ferry had been charged with and convicted by a military commission chaired by General Abner Doubleday of forging ballots of New York soldiers, changing them to votes for George McClellan and other Democrats. The plot was foiled by a New York (Clinton County) vote monitor, Orville Wood, who, though appointed by Democrat Governor Horatio Seymour, was a Lincoln supporter.

Perhaps Lincoln was curious about this voter fraud “unicorn” and/or was considering a pardon for Donahue. Of course, this actual fraud was miniscule and could not possibly have impacted the outcome of the election. Lincoln beat McClellan in New York by 6,549 votes (368,735 to 361,986).

WOMEN

On June 13, 1836, 27-year-old Abraham Lincoln wrote to the editor of the Sangamo Journal, published on June 18, 1836, stating his positions as a candidate for his first re-election to a seat in the legislature on two key issues: who shall bear the burdens of government and who shall share its privileges and distribution of proceeds of sales of public lands to the states to dig canals and construct railroads. Lincoln therein also plainly stated, “…I go for admitting all whites to the right of suffrage, who pay taxes or bear arms, (by no means excluding females).”

Some historians discount this comment, but Lincoln’s friend, fellow Whig and last and longest law partner, Billy Herndon was an early supporter of many social and political reforms, including the franchise for women. Herndon later said he believed that Lincoln’s “broad plan for universal suffrage certainly commends itself to the ladies, and we need no further evidence to satisfy our minds of his position on the subject of ‘Women’s Rights’ had he lived.”

Lincoln’s relationship with and thoughts on women are complex and require substantial further analysis, yet one would find it hard to discern in anything Lincoln said or did that would evidence any philosophical or moral opposition to the women’s suffrage. In fact, virtually everything he ever said about the franchise was gender neutral. As with many advancements, even though he personally may have preferred this, he knew it was far beyond his power to implement and the nation was not yet ready for it. As he would say during the Trent Affair with England, “One war at a time.”

BLACK MEN

As of September 18, 1858, Lincoln’s position was clear: “I am not nor have I ever been in favor of making voters… of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office….” As the war changed so many things, it would also change his mind on these issues. Less than four years later in his last address, on April 11, 1865, he would say, “It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.” Lincoln and the nation had evolved.

His suggestion in this last speech had actually been made a year earlier in private correspondence with Michael Hahn, governor-elect of Louisiana. Lincoln then used his “intelligent” condition (with “very” as a modifier) in his March 13, 1864, letter to Hahn. He never explained what he meant, but at a minimum he probably meant literate. Lincoln told one of his secretaries, William O. Stoddard, that the vote will be about the “only protection” Black people have after the war is over.

As Herndon had said of Lincoln’s view of women voting, Frederick Douglass, Lincoln’s friend, told audiences in Washington City and at the Brooklyn Academy of Music the year after the assassination, “Mr. Lincoln would have been in favor of an enfranchisement of the colored race, I tell you, he was a progressive man, he never took any step backwards.”

Historian Michael Burlingame argues that Lincoln was assassinated not for winning the war or freeing the slaves but rather for calling for even limited Black suffrage. Booth and his co-conspirators Lewis Payne and David Herold were in Lincoln’s audience on April 11, 1865, as was Frederick Douglass and Edward Bates, Lincoln’s first attorney general. When Lincoln expressed favor for some Black men to have the vote, it was the moment Booth expressed his plan to kill him, saying: “That means nigger citizenship. That’s the last speech he’s ever going to give. I’m going to run him through.” Up until that moment, Booth’s plans had always been to kidnap, not kill, Lincoln. If Lincoln was a martyr, it was as much due to Black men’s right to vote as anything.

ALIENS

Lincoln was known to often write anonymously for politically friendly newspapers. While some pieces attributed to him are of doubtful provenance, others are clearly his positions, written in his voice. The “Editorial on the Right of Foreigners to Vote” published in the Galena, Illinois, Daily Advertiser on July 12, 1856, is decidedly the latter. The position stated that unnaturalized foreigners residing in Illinois prior to the adoption of the then new state constitution could legally vote under Illinois law, which was Lincoln’s legal and political position. This “eight-point” style was also clearly his because 1) cites and states simply and clearly the opposing position, 2) restates the position as fairly and expansively as reasonable, 3) cites and quotes relevant legal authority, 4) cites and explains what the legislature did using that authority, 5) concludes, 6) advises those affected accordingly, 7) rhetorically causes readers to consider the implications of the opposite position, and 8) invites opponent to explain – all in ten sentences, five paragraphs. This style does not get much more Lincolnesque.

Lincoln reiterated his opposition to laws restricting the right of naturalized citizens to vote three years later. Writing to German American publisher Theodore Canisius, he said it was not his place “to scold” Massachusetts for its recent such constitutional provision, but he was “against it’s adoption in Illinois or any other place, where I have a right to oppose it.” “Understanding the spirit of our institutions to aim at the elevation of men, I am opposed to whatever degrades them,” and thus cannot “favor any project for curtailing the existing rights of white men, even though born in different lands, and speaking different languages from myself.”

VOTER ID

In Lincoln’s time few white men did and fewer were required to carry any type of identification or proof of legal status. Free people of color, however, were required to do so in many states as were enslaved persons when travelling off their enslavers’ land. In America then, and sometimes today, the chilling demand of “papers, please” is a prelude to some restriction of rights. No state required any type of identification for voting,[4] though when registering some proof of age, residence, duration of residence and/or race was often required, no doubt most often simply neighbor vouching. However, naturalized American citizens, who in Lincoln’s era had to be “free white persons,” were often suspected of not being qualified voters and thus subject to abuse by those who did not like the way they often voted.

On November 1, 1858, Lincoln authored and published in the Illinois Journal a bipartisan “Opinion on Election Laws” addressing this issue. He was joined by two other Whig lawyers, B.S. Edwards and his former law partner Stephen T. Logan, and concurred in by Democrat state judge Samuel H. Treat.

The brief, one paragraph, dry, legalistic opinion, relies on the Illinois State Constitution, the Illinois Election Law of 1849, and the effective portions of the Illinois Revised Code of 1848, and concludes simply that “any person taking the oath prescribed in the act of 1849, is entitled to vote” unless counter proof “satisfying a majority of the Judges that such oath is untrue.” This meant that any “foreigner” white male, 21 and over, resident of the county for six months prior and taking the oath was “entitled to vote,” or at least was presumed so in the absence of “counterproof” by a preponderance of the evidence.

As often times in politics, some do not recognize, understand, apply, or honor the law as written, especially in voting. Lincoln and his colleagues added some practical, preparedness advice to naturalized citizens upon going to vote—“take their papers with them.” In this present era of voter ID suppression laws, Lincoln’s suggestion bears repeating in its entirety:

“The Register of yesterday morning assumes that the Whigs will attempt to prevent our adopted citizens from voting today; and it advises them not to take their naturalization papers to the polls. By the opinion of three Whig lawyers and one democratic Judge, which we publish this morning, it seems the having the Naturalization papers at the polls is not indispensably necessary, but notwithstanding this, we would advise our friends among the adopted citizens to take their papers with them, as the shortest and easiest way of doing the thing up, in case of a controversy.”

Unsurprisingly, Lincoln did the right thing – he honestly and cogently explained the law and gave practical advice to assist those in voting who might be hampered, even though their votes were more likely to be for his political opponents. Eminently Lincolnesque.

VOTER SUPPRESSION LITIGATION

Lincoln sometimes refused to take an otherwise acceptable legal case when he disagreed with its merits or goal. So it was with a matter that his partner Billy Herndon, then also Clerk and City Attorney for Springfield, proposed to him shortly after Lincoln returned from his unremarkable one term in Congress in 1850. Lincoln refused to participate, telling his friend and partner simply and clearly, “I am opposed to lessening the right of suffrage and I am in favor of its extension and enlargement… I don’t intend by any act of mine to crush or contract suffrage.”

Years after Lincoln’s death, attorney Charles Shuster Zane recalled that when serving as Springfield City Attorney in 1858, he also had tried to engage Lincoln to serve as co-counsel in a similar case to deprive immigrants of the vote. Lincoln flatly refused, presumably for the same reason he had in 1850.

Neither the Collected Works nor the Legal Papers include any document evidencing that Lincoln was ever a litigant or counsel for any party in any election or voting irregularity dispute. As he handled virtually every other type of legal case imaginable and was as active in politics as any man, this absence is surprising.

LAST DISENFRANCHISEMENT

In ultimate irony, President Lincoln himself was disenfranchised by voting restrictions in his last election. Still as a resident of Springfield, Illinois, where he owned a home and business and intended to return, he was a registered voter there, not in Washington, D.C. The Illinois Constitution at the time required voting in person on Election Day, with no provision for absentee voting. Thus, he would have had to travel back to Springfield on November 8, 1864, to vote, a long journey away from his duties for a limited (one vote) purpose.

As Commander-in-Chief, he could have voted as many soldiers did, in the field. But unlike most states, Illinois did not make provision for same. The only active duty Illinois soldiers who voted were ones allowed to return home on furlough.

Even if he were considered a resident of Washington, he still could not have voted for himself, as Washington residents did not get the right to vote for president until a century later after the ratification of the Twenty-third Amendment.

Thus was Lincoln disenfranchised for yet a third time in his last and arguably most important election.

INSURRECTION

Violence interfering with any aspect of the franchise was anathema to Lincoln. On January 5, 1861, Lincoln wrote to his secretary of state-to be, New York Senator William H. Seward that the day that the electoral votes would be counted was the most perilous day for the Republic: “It seems to me that inaugeration [sic] is not the most dangerous point for us. Our adversaries have us more clearly at disadvantage, or the second Wednesday of February, when the votes should be officially counted… I think it best for me not to attempt appearing in Washington till the result of that ceremony is known.”

Although duly elected in a fair and valid election, Lincoln feared most not his inauguration, but what almost happened on January 6, 2021 – that the houses of Congress might refuse to meet or be prevented from doing so for the counting of the electoral votes. As Lincoln said, “Where shall we be?”

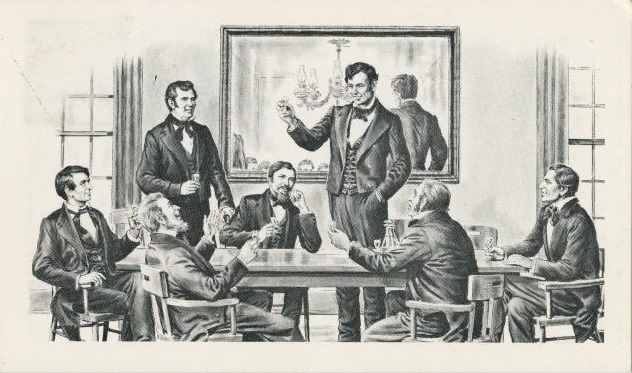

Washington City was on February 13, 1861, filled with thousands of armed District of Columbia volunteers, including cannons commanding the broad avenues, guards at every cross street, and sharpshooters atop prominent buildings. Fortunately for Lincoln, the Union and democracy, the Congress assembled and Vice President John C. Breckenridge (an unsuccessful candidate himself, wining the second most electoral votes) dutifully and uneventfully opened, counted, and announced the votes as required by Article II, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, certifying 180 electoral votes for Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States.

Lincoln friend and colleague Congressman Elihu B. Washburne (R-Ill.) was present on the day of count observing:

“…As in all times of great excitement, the air was filled with numberless and absurd rumors; a few were in fear that in some unforeseen way the ceremony of the count might be interrupted and the result not declared. And hence all Washington was on the qui vive.”

Somewhat ominously, however, Washburne continued, “Mr. Hindman, [Congressman Thomas C. Hindman of Arkansas] one of the most violent and vindictive secessionists, insisted that the … committee inform General Scott that there is no more use for his janissaries about the Capitol, the votes being counted and the results being proclaimed.” There was a certain feeling of relief among the loyal people of the country that Mr. Lincoln had been declared to be duly elected president, without the least pretense of illegality or irregularity.

John Palmer Usher, who served as Lincoln’s secretary of the interior, later also expressed surprise that the Secessionists allowed the electoral count to proceed without incident or even protest: “The secessionists dominated both Houses and they had it in their power to prevent the counting of the electoral vote.” Usher said that William Seward was “apprehensive that Mr. [Jefferson] Davis might inaugurate the rebellion before Mr. Lincoln was to be inaugurated – that he would resist the canvassing of the electoral vote.”[5]

Lincoln’s fears were reasonable, yet the nation was spared such electoral violence until just two months later at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861.

CONCLUSION

Lincoln’s words and deeds evidence that he stood for (1) expansion of the franchise to all adult citizens, (2) making voting legally and practically easier for all, (3) fair apportionment of districts, and (4) actual evidence of any claimed fraud and against (5) anything that would inhibit (1), (2), or (3), (5) fraud of any sort in the electoral process, and (6) violence or threats of violence in any aspect of the process.

M. Kelly Tillery practices law in Philadelphia. This article was first presented at the International Lincoln Center Conference in Shreveport, LA on October 22, 2022. It is a preview of Mr. Tillery’s book of same title to be published next year.

[1] The facts here are based on several documents set forth and cited in and the excellent discussion of same in Chapter 50 of Volume Four of Daniel W. Stowell, Ed., The Papers of Abraham Lincoln – Legal Departments and Cases (U. of VA Press, 2008), p. 64-91.

[2] Later, the capital “G” was reduced to lower case, the hyphen was eliminated and people started pronouncing it with a soft “g”, rather than the hard “g” of its namesake.

[3] In 1996, Congress prohibited non citizens from voting in Federal elections. 18 U.S.C. §611. State Constitutions in Arizona and South Dakota prohibit non citizens from voting in state and local elections. At least 15 municipalities allow non citizens to vote in local elections. Ballotpedia.org.

[4] Voter ID as a method of voter suppression (or dog whistle “election integrity”) was not “invented” until 1950. Unsurprisingly, South Carolina (Nullification Crisis – 1832; First to Secede 1860; First to Make War on Union – 1861) was the first state to require voter identification at the polls, the beginning of modern Jim Crow laws; “Voter ID History,” National Conference of State Legislatures. NCSL.org.

[5] Lincoln reportedly said, “that he would rather be hung by the neck till dead on the steps of the Capitol, before he would buy or beg a peaceful inauguration” One cannot help but wonder if Mike Pence had such a thought on January 6, 2021, as insurrectionists chanted “Hang Mike Pence” in their shadow of hastily-erected gallows.