Lincoln, The Founders, and the Rights of Human Nature

If they had bumper stickers for carriages back in Lincoln’s day, his would say:

“I ❤ the American Founding.”

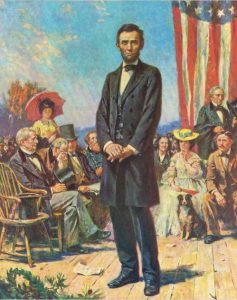

It’s true that one can see the influences of the Bible, Shakespeare, and later political examples like John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Henry Clay in Lincoln’s speeches. But there was no greater influence on Abraham Lincoln’s statesmanship than the leading men, and especially the seminal ideas, that shaped America’s revolution and early constitutional formation.

I drew this lecture from a book I’ve written—”Lincoln and the American Founding,” to be published next July—which is a scholarly introduction to the impact of the American founding on Lincoln’s political thought and practice. The leading political principles I highlight in the book derive from the argument presented in the opening two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence. As Lincoln said en route to his first inauguration as president, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” Several years before his election and the ensuing civil war, Lincoln summarized his approach to the increasing conflict between the free and slaveholding American states: “Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it. . . . If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union; but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving.”

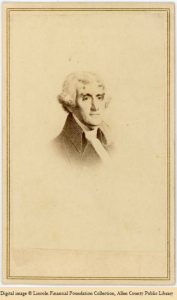

[ Book summary: Let me give a quick outline of my book, and then I’ll walk through the basic argument the book, which shows how Lincoln drew from the American founding to help him navigate the disputes and controversies that threatened to divide the American union. The book has 5 chapters. Chapter 1 explains the influence of George Washington, the indispensable Founder. But for Lincoln, more important than a founding man was a founding document, the Declaration of Independence. So I devote Chapter 2 to the influence of the Declaration, and to some extent, its chief draftsman, Thomas Jefferson. Chapter 3 explains the influence of the U.S. Constitution on Lincoln’s thinking and practice as a citizen and politician. It was the most important means that the Founders established to secure the ends spelled out in the Declaration of Independence. ]

In Chapter 4, I turn to what Lincoln learned from the Founders’ compromise with slavery, the institution that contradicted the Founding experiment in self-government. Lastly, Chapter 5 explains Lincoln’s understanding of original intent as a political practice. In short, why should subsequent generations of Americans follow the Founders? This chapter examines how Lincoln understood his own respect for the American founding in light of progress, experience, and the responsibility of each generation to govern themselves under the Constitution.

My book takes us on a journey: From Founding Father (George Washington), to Founding Purpose (described in the Declaration of Independence), to Founding Means (the Constitution), to Founding Compromise (slavery butting heads with federalism), to Founding Significance (or, why Lincoln thinks the original intention of the Founders matters).

Lincoln believed that during his fractious times, looking back to the Founding could provide guidance on how to perpetuate American self-government. He did this most famously in his Gettysburg Address. That speech begins at the nation’s beginning: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” If you do the math, you find that he takes his audience back not to the Constitution, but to the . . . Declaration of Independence. Not to the body but to the soul of the nation. If America stood for anything, it was liberty and equality. Lincoln goes on to explain that the Civil War was a test of America’s purpose: as he put it, “whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure.”

In the midst of a fight for the very survival of the United States—a civil war—, Lincoln thought the nation would benefit from looking to its past. Americans needed a reminder of why preserving their Union was so important. So Lincoln sought to clarify what was at stake. With Americans shooting not at an external foe but at each other, it’s safe to say there was some confusion about the meaning of America. They were no longer united in their understanding of why the nation existed—what were its highest aims and purposes. So Lincoln wanted Americans to recommit themselves, to dedicate themselves, to the task that remained: to honor the dead who fought at Gettysburg on behalf of the Union, by joining and supporting that fight. It was a fight to defend a certain political way of life, what Lincoln called “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Recall that Lincoln delivered his short speech in the Year of Jubilee, the year of emancipation. Union soldiers and sailors were now charged by the president to protect the freedom of over 3 million, newly emancipated black people. What Lincoln called “a new birth of freedom” was tied directly to the old, original birth of freedom, our first emancipation proclamation, the Declaration of Independence. Its principle that “all men are created equal” described all human beings. So at Gettysburg, Lincoln did not announce a new principle of freedom, but affirmed an old one—what he argued was its original one. He never sought to discover new rights for a new age; or for that matter, he never spoke of a “living constitution,” one where a visionary few would discern what would benefit the many. Instead Lincoln spoke of “the unfinished work” to which the living could dedicate themselves. In this way, they could honor the men who fought at Gettysburg—those “who gave their lives that that nation might live.”

This was no Civil War epiphany of Lincoln’s. In February 1861, en route to his first inauguration as president, he stopped in Trenton, New Jersey, and told the state senate: “I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made.” I suspect many today would think that this is rather controversial. After all, weren’t the founders—at least some of them, even the most famous of them—slave owners? Why would Lincoln want to lean on that generation, long dead and gone, for political guidance in his day and age?

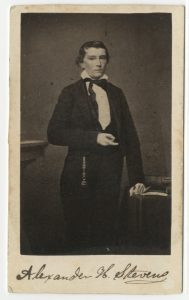

Our temptation today is to think that everything new is by definition improved, better than what’s old, what we used to call “the tried and true.” But in Lincoln’s time, there were some Americans arguing for something new, an improvement over the American founders. Consider Alexander Stephens of Georgia, a former Whig colleague of Lincoln’s during Lincoln’s sole term in Congress. As the Vice President of the Confederate States of America, Stephens argued that their Constitution was a better one than the old one Lincoln was trying to preserve. It was better not simply because it protected slavery by mentioning it explicitly, where the original constitution did so implicitly. There were plenty of people, plenty of regimes throughout human history, that practiced slavery. Alexander Stephens argued that the Confederacy was the first to base its slave society on white supremacy.

Unlike the American founders, who Stephens acknowledges believed that

“the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically,” the Confederate government was “founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” He added, “This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” The American founders, in his mind, saw slavery as “an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but . . . somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away.” Stephens argued that the anti-slavery principles of the Founding “were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races.” He called this “an error” and “a sandy foundation,” unlike the new and improved constitution he helped write for the Southern Confederacy.

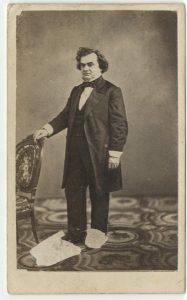

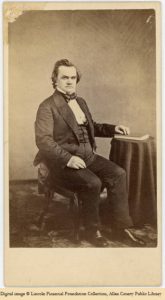

Nevertheless, in the decade leading up to the Civil War, Lincoln’s main political target was not slave-owning southerners, but complacent white northerners, like his Illinois rival Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln criticized Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” policy because of its neutrality—its moral indifference—on the slave question, and its insistence that whites at the local level—whether in the states or federal territories—reserved the right to decide the question without interference from Congress. In other words, the future of slavery or freedom in the United States, under this policy of local “popular sovereignty,” would not be determined, ironically enough, by the vast majority of American citizens, but by a very small majority of settlers who went to live in the western territories.

This indicated to Lincoln, that the most urgent threat to the expansion of freedom in the United States, was the temptation of white northerners to become indifferent to the plight of blacks in the federal territories. What made Douglas’s “don’t care” policy about slavery in the territories, so insidious, was that for slavery to become national, it did not require a full-throated defense of the peculiar institution. Rather, simply promote indifference or tolerance on the part of free-state whites, towards the enslavement of blacks in the territories. Eventually those slave territories would become additional slave states of the American union.

This is why “looking back” was no exercise in nostalgia or some abstract consideration by Lincoln. It couldn’t have been more relevant to the developing crisis the nation faced in the 1850s. Lincoln’s trip down memory lane was a contested one. Stephen Douglas, the most prominent Democrat of the 1850s, claimed he knew better what the Founders thought about the question of slavery, and claimed his policy proposal aligned more closely with the Founders’ hopes for the new republic. In Lincoln’s mind, the future of freedom and the eventual demise of slavery depended on whose interpretation of the Founders was correct and could help unite a divided country.

Lincoln argued that in the beginning, at the founding of the United States, slavery was viewed and treated as a “necessary evil.” But it had become in the South, to quote South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun, “a positive good.” It was also true at the beginning, that where slavery already existed in the states, Congress had no authority over the matter because of the federal nature of the U.S. Constitution. It was considered a “domestic institution,” governed only by state authority. Government powers, since the beginning of the United States, were divided between the state governments and national government. And slavery, as it existed prior to the formation of the United States, remained a state institution, and therefore could not be abolished by Congress, short of a constitutional amendment.

Given the greater population growth in the free states than in the slaveholding states, this meant that the spread of slavery or freedom in America would be decided by the votes of northern whites, who according to Lincoln could use federal authority to ban slavery in the only area they had jurisdiction over internal affairs—the federal territories. Territory owned by all the citizens, could be regulated by those same citizens, and that meant Congress. However, tempted by Stephen Douglas’s popular sovereignty, slavery’s fate might be determined not by moral right but by mere self-interest—meaning those who could profit by taking black slaves into the territories. If free-state whites agreed with Douglas that Congress did not have authority to regulate the domestic affairs of the territories, then his “declared indifference” would actually represent, in Lincoln’s words, “covert real zeal for the spread of slavery.” And so Lincoln was at pains to tie the future security of the rights of whites, to the present in-security of the rights of blacks. Those same white Americans would have to decide if what happened to a people that did not look like them—black slaves in the South potentially being taken into federal territory—had anything to do with the kind of country in which they wanted to live. For Lincoln, the necessary connection could be found in the thinking of the American founders.

So why does the founding, the beginning of America, deserve Lincoln’s respect? Discussion of original intent is important not simply because it came first. After all, not all old things are worth holding onto. What if the Founders were wrong? To be sure, an old government should not be rejected simply because it is old. Nevertheless, as we see in Lincoln’s consideration of the American founding, to preserve what is old—even one’s form of government—requires a justification most importantly on its merits. Later generations of American citizens should follow those older intentions because they are worthy of their respect: which is to say, because they are good. If not, then it stands to reason that what is no longer seen as good—no longer true in principle, nor useful in practice—should be replaced by something better.

Lincoln addressed this concern regarding original intentions in his 1860 Cooper Institute speech. It was a speech designed to make him a credible candidate for the Republican nomination for the presidency. He said:

I do not mean to say we are bound to follow implicitly in whatever our fathers did. To do so, would be to discard all the lights of current experience—to reject all progress—all improvement. What I do say is, that if we would supplant the opinions and policy of our fathers in any case, we should do so upon evidence so conclusive, and argument so clear, that even their great authority, fairly considered and weighed, cannot stand . . .

Lincoln allows that differences of opinion over what policy to pursue will emerge not only from a dispute between the old ways and the new ways, but also between interpretations of the old ways among those who believe the old ways are the best ways.

He goes on to say:

If any man at this day sincerely believes that a proper division of local from federal authority, or any part of the Constitution, forbids the Federal Government to control as to slavery in the federal territories, he is right to say so, and to enforce his position, by all truthful evidence and fair argument which he can. But he has no right to mislead others, who have less access to history, and less leisure to study it, into the false belief that “our fathers, who framed the Government under which we live,” were of the same opinion . . .

Of course, Lincoln has Stephen Douglas in mind here. Both men greatly respected the founders, but they differed in their interpretation of what the founders intended.

To his credit, Lincoln said out loud, in that pivotal campaign year of 1860, that Americans were free not to follow what is old, even the founders of their country, if experience and argument lead them to think they could improve on their old political beliefs and practices. That said, Lincoln hastened to add that he did not see a better way forward for the country—given the crisis facing them regarding the future of slavery in their republic—than the mode adopted by the founders. He thought Stephen Douglas’s respect for the American founding was actually a misinterpretation of their intentions. “Popular sovereignty” was actually a sham because it treated slavery “as something having no moral question in it.” And Alexander Stephens’s outright rejection of the American founding was deficient in comparison with founders dead and gone. Although Lincoln’s generation faced different challenges than those of the founders, he did not suggest that the primary means and ends were to be tossed for the sake of newer interpretations of those means and ends, let alone newer principles or institutions.

The question of innovation and progress, versus original intention, is an important one. Lincoln acknowledges that experience could lead to progress and improvement. Nevertheless, with regards to slavery, the experience of free white southerners enslaving black people, led some whites to make new arguments on behalf of slavery. Lincoln believed they were wrong—an example of how the new did not improve upon the past.

Contrary to Douglas and Stephens, Lincoln thought the Founders saw the toleration of slavery only as a necessary evil. After the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened territories north of the 36° 30’ parallel to the possibility of slavery, contrary to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Lincoln contrasted the Founding era with the degeneration of his own times. He detailed the many ways that older generation restricted the further entrenchment of slavery in America by stopping it at its source, as well as limiting its spread into federal territories—all in the hopes that slavery was being put “in the course of ultimate extinction.” Lincoln concluded:

The plain unmistakable spirit of that age, towards slavery, was hostility to the PRINCIPLE, and toleration, ONLY BY NECESSITY.

But NOW it is to be transformed into a “sacred right.” Nebraska brings it forth, places it on the high road to extension and perpetuity. . . Little by little, but steadily as man’s march to the grave, we have been giving up the OLD for the NEW faith.

Instead of the new faith of Douglas’s crude majoritarianism, which rejected the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal,” Lincoln preached a return to the old faith, the faith of the founding fathers: “Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust,” Lincoln declared.

Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution. Let us turn slavery from its claims of “moral right,” back upon its existing legal rights, and its arguments of “necessity.” Let us return it to the position our fathers gave it; and there let it rest in peace.

Catch the pun? Lincoln went on to call Americans to “re-adopt the Declaration of Independence.” In so doing, they would “not only have saved the Union,” but “so save it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving.” That was October of 1854. A country worthy of the saving needed to be a country limiting the spread of slavery, not expanding it. A few months later, Lincoln came within five votes of being appointed to the U.S. Senate by a coalition of anti-Nebraska Democrats and Whigs in the Illinois state legislature. That was a few years before his more famous campaign against Stephen Douglas, and six years before his election as the first Republican president of the United States.

After that election, but before he assumed the presidency, Lincoln received a letter from none other than Alexander Stephens, who would later become the Vice President of the Confederate States of America. Stephens wanted the president-elect to speak to the nation before the inauguration—in his words, “to save our common country.” Quoting Proverbs 25, Stephens suggested to Lincoln that, “A word fitly spoken by you now would be like ‘apples of gold in pictures of silver.’”

This led Lincoln to jot a note to himself—a reflection on what he called the “philosophical cause” of American prosperity. For someone who had long revered the Constitution, and saw the union of the American states as essential to the success of the republic, he wrote that “even these, are not the primary cause of our great prosperity.” His note continued:

There is something back of these, entwining itself more closely about the human heart. That something, is the principle of “Liberty to all”—the principle that clears the path for all—gives hope to all—and, by consequence, enterprize, and industry to all. . .

The assertion of that principle, at that time, was the word, “fitly spoken” which has proved an “apple of gold” to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made,

not to conceal, or destroy the apple; but to adorn, and preserve it. The picture

was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture.

So let us act, that neither picture, or apple shall ever be blurred, or bruised or broken.

As Lincoln saw it, more important than new words from him, was old words—from the founders, from the nation’s founding charter—the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln saw the Declaration’s principle of “Liberty to all” (human equality and individual rights) as the moral center of a Constitution and American union, that could otherwise be misinterpreted—or destroyed—in pursuit of other ends. For Lincoln, the Constitution and union of the states were the means of achieving the political ends defined in the Declaration of Independence.

To state that the Declaration of Independence was the lodestar of Lincoln’s political life would be an understatement. The Declaration was the sine qua non of Lincoln’s political thinking. Without its influence the Gettysburg Address would be unrecognizable; the Emancipation Proclamation and 13th Amendment would lack their moral purpose; and the Civil War would not have been fought as a war to save republican government, and ultimately expand the protection of rights to all Americans.

A year before he was elected president, Lincoln was asked to give a speech in Boston upon the anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s birth. He couldn’t make the trip, but sent a letter that was essentially an ode to Jefferson’s achievement in drafting the Declaration of Independence. He wrote that “the principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society.” For someone who studied Euclid’s geometry while in Congress, Lincoln was referring to the Declaration’s principles as the building blocks of democracy. Unfortunately, even self-evident truths can be “denied, and evaded,” as was the case in 1859. Lincoln said: “This is a world of compensations; and he who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave.” Borrowing from Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, he observed that, “Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just God, can not long retain it.”

These were astounding words for a Republican, a former Whig, to utter. After all, Jefferson was a states’ rights Democrat, not a National Republican. And yet, Lincoln declared:

All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.

Lincoln saw the principles of Jefferson, America’s principles, as universal, timeless, and transcendent. Lincoln looked back to the founding generation and saw ideals of human nature and legitimate government that he believed applied in his day and forever more. He understood that according to Jefferson’s logic, if they applied to anyone, they applied to everyone, at any time, and any place. This was key to Lincoln’s eventual role as the emancipator of black slaves in America—which he derived from the principle of equality to which he thought the nation had long been committed, until it began to lose its way in the mid-1850s.

In a speech at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, another stop on his way to his first inauguration, he had this to say about the universality of the principles of the Declaration: “All the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn . . . from the sentiments which originated, and were given to the world from this hall in which we stand.” He said that he “never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence,” and then he mused out loud about “what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy so long together.” He argued that the Declaration was more than just about separating from England; he said it gave “liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.” Lincoln believed that the Declaration unified the citizens of the diverse thirteen American colonies, and the Constitution that replaced the flawed Articles of Confederation, a league with no direct authority over the citizens of each state, the Constitution helped “form a more perfect union.” ]

But we all know that in addition to Jefferson, other signers of the Declaration were slaveholders; ditto for the framers of the U.S Constitution, which after all, made several compromises with slavery. Lincoln was aware of these facts, and aware that slavery stood as the grand contradiction to the very principles of the American Revolution. But he believed that even though the founders did not abolish it right away, this did not mean that they approved of slavery as a morally just practice. How should we understand this?

Lincoln is best known for two political accomplishments: preserving the American union and emancipating slaves. How he approached the abolition of slavery owes much to his interpretation of how the American founders approached the difficulty of slavery in their midst, as they sought to establish not just their independence from Great Britain, but also a way of life based on the principle of human equality.

Lincoln’s anti-slavery convictions were the very thing that informed his devotion to the Constitution. Like the founders, he believed that, but for the American union, there would be no freedom—for whites or blacks. This was no innovation on Lincoln’s part, but rather the abiding conviction of Americans who knew their colonial and revolutionary history. Individual freedom required political independence from foreign powers; and political independence required domestic unity. To keep the union of American colonies, then states, required that compromises be made regarding slavery. As Lincoln once said, “We had slavery among us, we could not get our Constitution unless we permitted them to remain in slavery, we could not secure the good we did secure if we grasped for more, and having by necessity submitted to that much, it does not destroy the principle that is the charter of our liberties.”

Time and again, Lincoln’s references to the founders centered on how they tried to establish a government based on human equality, but by that very equality, imposed upon themselves the requirement that slavery be abolished in a manner consistent with the consent that was the flip side of the equality coin. As he put it in an 1864 letter:

If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling.

This distinction between “official duty” and “personal wish,” a distinction he made most famously in his 1862 public letter to Horace Greeley before Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, demonstrates most clearly Lincoln’s concern that Americans follow the rule of law in their pursuit of justice. That in America, the means of securing liberty needs to be consistent with the end. In emancipating slaves, as president, in a time of war, Lincoln had to turn a humanitarian end into a constitutional means in order to make emancipation a legitimate action of the national government.

The connection between constitutional means and ends is one, I think, we have lost sight of today, and it has shaped how most historians interpret Lincoln’s statesmanship. The reigning interpretation of Lincoln today finds him most relevant to our times because of what consensus historians see as his openness to change. This progressive Lincoln got better as the nation got worse, with a good number of its white citizens grown indifferent toward the spread of black slavery into federal territory, while others fought to defend a way of life where white supremacy was the explicit rule and not the exception.

This version of Lincoln is worthy of our twenty-first-century esteem only if he exhibits virtues that shine brightest when distanced from his country’s slaveholding founders. After all, few of the founders freed their own slaves, or strove to rid the new nation of the “peculiar institution.” If Lincoln is to be praised, his love of the founders, especially Thomas Jefferson, needs to be minimized if not altogether muted.

Thus what makes the Emancipator so great in the eyes of succeeding generations of Americans must be his capacity for growth, a figure embraced by future generations who, presumably, have progressed and improved upon the past to the extent they followed Lincoln’s example, of not being too fixed in one’s views and of being open to the light of experience and progress. Lincoln understood simply as a man focused on the future, becomes a man who did not know early on what he believed about America, or what he hoped for the nation.

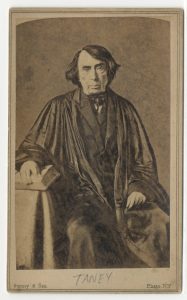

I disagree with this interpretation. On my reading, Lincoln’s greatness is due largely to his recognizing and appreciating what the founders had accomplished despite the pre-existing problem of slavery. Lincoln chose to offer an alternative view of the founding to counter the incorrect view promoted by influential figures such as Chief Justice Roger Taney and Senator Stephen Douglas. Unlike Lincoln, Taney and Douglas thought the Declaration of Independence was true only for white people, and they read it that way to protect the slaveholding founders from charges of hypocrisy. In 1857 Taney wrote that “the men who framed this declaration were great men—high in literary acquirements, high in their sense of honor, and incapable of asserting principles inconsistent with those on which they were acting.”

A year later, Stephen Douglas echoed this sentiment: “If they included negroes in that term [‘all men’], they were bound, as conscientious men, that day and that hour, not only to have abolished slavery throughout the land, but to have conferred political rights and privileges on the negro, and elevated him to an equality with the white man.” To make profession and practice consistent at the American founding, thereby establishing an integrity worth admiring for subsequent generations, Taney and Douglas interpreted the founders’ profession in light of their practice. So if the founders did not free their slaves and abolish the peculiar institution, then they must not have seen Africans as “created equal” to Englishmen or their descendants.

In response to the Dred Scott opinion of 1857, Lincoln commented on the equality principle stated in the Declaration of Independence. On his reading, the Founders “did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, nor yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact, they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.” Lincoln understood the reticence of the founders not as hypocrisy but as prudence: they recognized that circumstances, like British opposition, could impede their attempt “to secure these rights.”

Furthermore, Lincoln pointed out that their inaction regarding black slaves in their midst was no different than their inaction toward white citizens on American soil: “They did not at once, or ever afterwards, actually place all white people on an equality with one another. . . . They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which could be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, . . . and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

To sum up the Founding compromise with slavery: to be free, Americans had to be independent. And to be independent, they had to be united. That political unity—what the Constitution would call “a more perfect union”—required concessions to slaveholding states, which were unable or unwilling, in the near term, to extricate themselves from their dependence upon slavery, while they established the institutions and habits of self-government. Put simply, the founding generation of Americans did not believe they could both free themselves and their slaves without hazarding the success of both their independence and their new way of governing themselves. Lincoln’s respect for the American Founding, which established an independent nation devoted to “secur[ing] the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity,” recognized both the noble end to which that nation was founded, and the prudent means adopted to achieve that end.

Time and again, as the controversy over slavery threatened to split the nation, Lincoln returned his audience to the words of the Declaration of Independence. There he hoped they would find clarity about the true principles of self-government, and thus common ground for promoting a common future as a truly free people. To keep Lincoln relevant, our task should not be to remake him in our image, but to render an accurate portrait of him in his age. He spoke to his own era with sufficient transcendence not only to enable Americans then to surmount their difficulties, but also to teach subsequent generations how to address the abiding questions that confront a free people. Lincoln “belongs to the ages” as a teacher of profound lessons regarding the nature of the American regime, and how Americans from generation to generation, could preserve and perpetuate our free system of government. With Lincoln, we find no blind follower of the American founding, but a thoughtful and thought-provoking citizen who became a statesman by reaching back to the founders, and making the case that what they achieved was the best, most prudent, means of securing their safety and happiness.

Lucas Morel is a professor at Washing and Lee University. This article was presented at Ashland University’s Summer MAHG Program.