LINCOLN, DOUGLASS, & THE POLITICS OF RACE

LINCOLN, DOUGLASS, & THE POLITICS OF RACE

EDNA GREENE MEDFORD

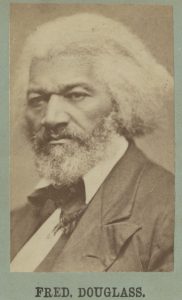

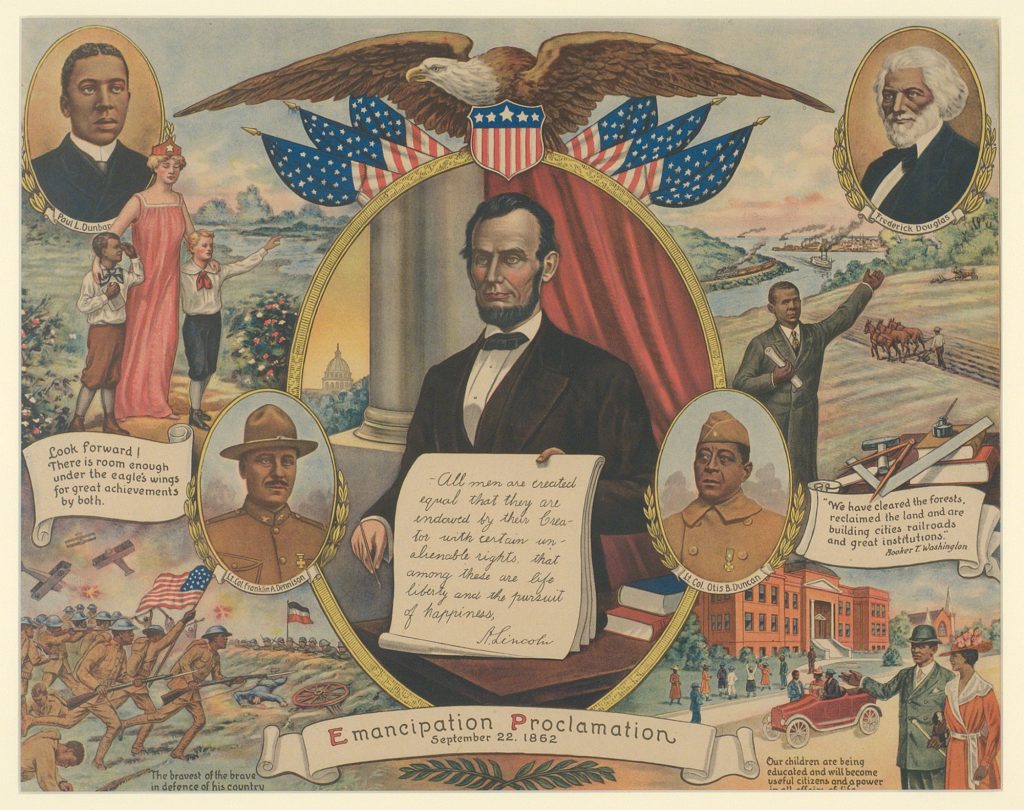

A few weeks before the 1864 presidential election, Frederick Douglass penned a letter to Theodore Tilton, an abolitionist and the editor of The Independent, a New York newspaper. Referring to the impending election, Douglass wrote: “To all appearance [the Republicans] have been more ashamed of the Negro during this canvass than those of 56 and 60. . . . I am not doing much in this Presidential canvass for the reason that the Republican committees do not wish to expose themselves to the charge of being the Nigger party.” Frustrated by the party’s discomfort with some of the more radical ideas of its supporters, Douglass declared that “The Negro is the deformed child, which is put out of the room when company comes.”

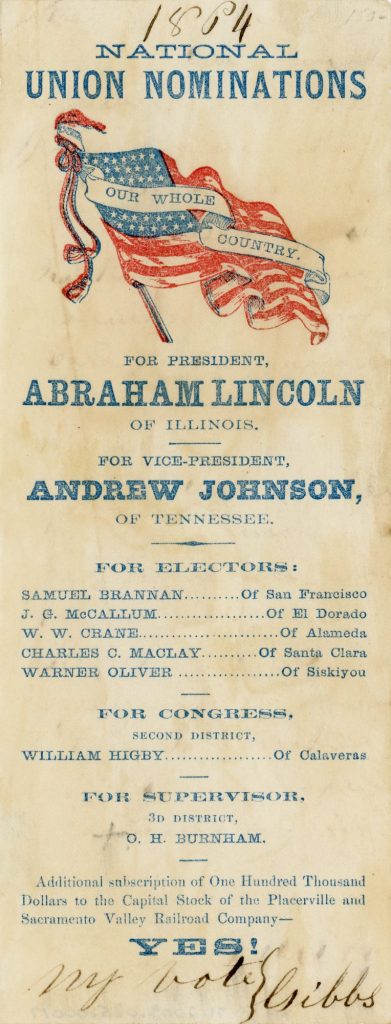

Douglass’s blunt assessment of the relationship between the Republicans and African Americans reflected the political realities of the day. Many in the party would indeed have considered African American canvassers a political liability, especially someone like Douglass, who was pressing not just for abolition but for political and social equality as well. The party leaders had temporarily changed the name of their organization to the National Union Party to attract War Democrats, but the term “Black Republicans” continued to be used as a pejorative by those who sought to link it to the quest for racial equality. Douglass and others of like mind complicated the effort of Republicans to distance themselves from what was an unpopular position. Continued agitation from “Fred” Douglass, they feared, could upend the delicate alliance that the party hoped would keep Lincoln in office.

The tension between advocates of racial equality and those who were simply antislavery had been of long standing. In the years before the Civil War, racial equality was neither widely expected nor accepted by white Americans, even the abolitionists. For many (perhaps most) it did not matter if the Black man or woman was enslaved, free, unlettered, educated, crushed by poverty, or economically secure. Whiteness was the standard that determined the extent to which Americans would be permitted to partake of the nation’s many opportunities, and most Americans accepted this. The 1857 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford reflected prevailing public sentiment. The Court declared that African Americans “had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order,” that they were not citizens of the United States and hence were not entitled to the protections enjoyed by other Americans. Free Black men and women contested such assertions. They declared that it was bigotry that imposed disabilities on African Americans and prevented their advancement: “We meet the monster prejudice everywhere,” one complained. “We cannot elevate ourselves . . . prejudice follows us everywhere, even to the grave.”

Douglass was among the most persistent and influential voices proposing equality between the races. Since his self-emancipation at the age of twenty, he had pressed for the liberation of his brothers and sisters in bondage, initially aligning himself with the Garrisonians, who called for immediate abolition, joining the antislavery lecture circuit, chronicling his life under slavery in autobiography (three in all), and publishing editorials against the institution in his own newspapers. However, his crusade against slavery was but one component in the struggle to obtain rights for all African Americans. He was an active participant in the Black conventions that were held pre-Civil War to bring attention to the plight of both enslaved and free Black men and women. An 1849 editorial in his newspaper, The North Star, summed up his views:

It is evident that white and black ‘must fall or flourish together.’ In the light of this great truth, laws ought to be enacted and institutions established—all distinctions founded on complexion, ought to be repealed, repudiated, and for ever abolished, and every right, privilege, and immunity, now enjoyed by the white man ought to be as freely granted to the man of color.

Several years later, Douglass used his oratorical prowess and skill with the pen to respond swiftly and aggressively to the Dred Scott decision. He argued that the Constitution makes “no distinction in favor of, or against, any class of the people, but is fitted to protect and preserve the rights of all, without reference to color, size, or any physical peculiarities.” He encouraged Americans to rely on the Constitution, embrace its principles and spirit, and enforce its provisions.

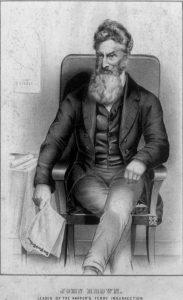

In his personal life as well, Douglass epitomized the idea of racial equality. Fellow abolitionist John Brown was a weeks-long guest in his home. Both Julia Griffiths (Crofts), an Englishwoman who assisted Douglass in editing The North Star, and Ottilie Assing, a German woman who translated into German Douglass’s autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom, had long-term personal and professional relationships with him and had extended stays in his home. His habit of escorting white female friends and acquaintances such as Griffiths and Assing around town provoked sharp criticism from white observers who suspected a romantic involvement.

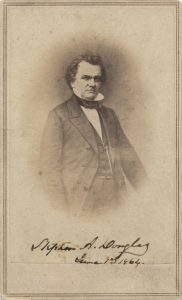

Hence, it was not surprising that Stephen A. Douglas, a shrewd politician skilled in race-baiting, would reference Frederick Douglass in the Illinois senator’s campaign for reelection in 1858. In the seven debates with Lincoln, the Democrat, Douglas, took advantage of the racial sensibilities of the day to portray his challenger and the Republicans as proponents of citizenship and full equality for African Americans. In Freeport, and later in Jonesboro, the senator attempted to place Lincoln in the abolitionist camp and suggested that Frederick Douglass was one of Lincoln’s advisers. Then, in words meant to incite disgust from whites and fear of race-mixing, the incumbent declared that in an earlier visit to Freeport, he had witnessed an incident that reflected the agenda of the Republicans. Senator Douglas claimed that he had seen a white man driving a carriage in which a “beautiful young lady,” presumably the driver’s daughter, sat on the box-seat “whilst Fred Douglass and her mother reclined inside.” He suggested that those who found such behavior acceptable would vote for Lincoln. Again, in Jonesboro, on September 15, Senator Douglas repeated the story in abbreviated form, but doubtless with the same effect. He also argued, in opposition to Lincoln’s views, that the signers of the Declaration of Independence did not intend to include Black people, or “any inferior and degraded race,” in its assertions of equality for all men.

Three days later, at the infamous Charleston debate, Lincoln responded to his opponent’s accusations. In explicit language that was meant to allay the concerns of pro-southern residents of the region, Lincoln declared that he was not and never had been in favor of racial equality. Nor did he favor extending voting rights to Black men or permitting them to serve on juries or become office holders. Anyone who opposed race-mixing was assured as well that he did not support intermarriage. Lincoln asserted that the physical differences between the races were so great that they would preclude the two groups from living as social and political equals. Consequently, one race would have to occupy the superior position and the other an inferior one. During the debates with Douglas, Lincoln also defended his position on the intent of the Declaration of Independence. He suggested that while the signers of the Declaration intended to include all men as equal, they did not mean to declare all men equal “in all respects.” All men were not equal in color, size, intellect, or moral development and moral capacity; but they were equal in their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Although Lincoln did not win the senatorial race, his debates with Douglas provided him with the opportunity to hone his thoughts on the issue of slavery. Over the next two years, his carefully prepared remarks on the aim of the Founders regarding slavery, and the Republican Party’s objection to the extension of the institution into the territories, made him recognizable as a significant political actor within and beyond Illinois. His moderate position on slavery—he was not yet an abolitionist—advantaged him over politicians who were more radical in their thinking.

A year following the debates, Lincoln and the Republican Party faced the fallout from John Brown’s abortive raid on Harpers Ferry. The Democratic-leaning press seized on the opportunity to blame Republicans, especially after they learned of the satchel of letters and documents he left behind implicating prominent abolitionists. To the New York Herald, for instance, this was a “vast conspiracy, aided by the funds of wealthy men, and encouraged by black republican politicians and other fanatics.” At the very least, the Herald argued, Republican antislavery agitation fed the lunacy of John Brown and prompted him to carry out such an absurd plot.

Unfortunately, Frederick Douglass found himself implicated in the raid. John Cook, one of Brown’s lieutenants, alleged that Douglass had promised to recruit men for the cause and bring them to Harpers Ferry. On that information, Virginia governor Henry Wise swore out a warrant for Douglass’s arrest. Hearing this, Douglass left the United States for England and remained there until the death of his daughter, Annie, compelled him to return home a few months later. The investigation of Douglass collapsed, but he was linked in the minds of members of the Republican Party with a violent attempt to liberate enslaved people.

Despite his more radical position on slavery, Douglass found reason to favor the Republican Party and its candidate in the 1860 campaign. “While we should be glad to co-operate with a party fully committed to the doctrine of ‘All rights to all men,’” he wrote, “in the absence of all hope of rearing up the standard of such a party for the coming campaign, we can but desire the success of the Republican candidates.” As for Lincoln, Douglass found him to be a man of “unblemished private character . . . great firmness of will . . . and one of the most frank, honest men in political life.”

The praise would change to condemnation after the November election. Lincoln’s victory prompted several southern states to secede, and by the time he took the oath of office, attempts to return the wayward slaveholding sisters to the fold had failed miserably. Douglass feared that the new president and his party would broker a peace that would not only leave slavery intact but would strengthen it. The inaugural address confirmed the validity of that concern. Lincoln disappointed the abolitionists, especially Douglass, by declaring that he had no lawful right nor was he inclined to interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed. His aim was to reunite the divided nation. Until that time, he would work to ensure that all “domestic institutions” were protected.

Douglass was especially agitated that Lincoln declared his support for the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The law was one of several compromises that aimed to quiet tensions arising over the territory ceded by Mexico after the war of 1846–1848. One of the most undemocratic measures ever to be enacted, it required the free states (including both public officials and private citizens) to assist in the apprehension of runaways. A federal court would determine the status of the alleged slave, but the accused could not testify on his or her behalf and was not entitled to a jury trial. Commissioners (who presided in the place of federal judges) were paid more to find in the supposed owner’s favor than they were if they found for the accused. Douglass charged that the president

has avowed himself ready to catch [enslaved men and women] if they run away, to shoot them down if they rise against their oppressors, and to prohibit the Federal Government irrevocably from interfering for their deliverance. With such declarations before them, coming from our first modern anti-slavery President, the Abolitionists must know what to expect during the next four years.

Douglass did not temper his criticism of Lincoln when war erupted a few weeks later. Like most Black leaders, he believed northern victory could be secured rather quickly with the employment of an army of Black liberators. Armed African Americans could free the enslaved population and both could be employed to put down the rebellion. Black men offered their services at the very beginning of armed conflict, but fear of angering the Border States and the belief that Black men lacked the courage to face white men on the battlefield led the Lincoln administration to decline to accept them as soldiers. Douglass noted that the Confederates were using their enslaved laborers to great advantage, while the North refused to act. “Every consideration of justice, humanity, and sound policy confirms the wisdom of calling upon black men just now to take up arms in behalf of their country.”

Douglass used the phrase “their country” purposely. Although the Dred Scott decision ruled that African Americans were not entitled to the same rights as other Americans, he insisted that they were indeed citizens and that they had always supported the nation in all its wars. But patriotism had its limits. The Black response to the war was shaped by the desire for freedom—for the enslaved and for those who were legally free but who continued to be constrained by prejudice. So even as Douglass pressed for the acceptance of Black men into the Union army, he cautioned that until the North recognized the reason for the rebellion and struck down the institution of human bondage, it did not “deserve the support of a single sable arm.”

Congressional action in the spring of 1862 elicited a positive response from the former bondman. Congress controlled the District of Columbia, a federal enclave, and as such, had the authority to end slavery there. In April, the legislators approved a bill that emancipated the nearly 3,200 enslaved laborers in the city. District slaveholders received an average of $300 to compensate them for the loss of each laborer. Of course, the formerly enslaved received nothing for their uncompensated toil. Nevertheless, Douglass declared District emancipation to be “the first great step towards that righteousness which exalts a nation.” He could not have been pleased, however, that the government saw fit to appropriate $100,000 to be used for colonizing the emancipated to either Haiti or Liberia.

During the summer of 1862, Douglass returned to his scathing criticism of the Lincoln administration. In a speech on July 4, he characterized the administration as weak, imbecilic, and unfaithful. He accused Lincoln of being overly influenced by the interests of the Border States, allowing certain generals to return runaways, and pursuing a policy that was meant to return the Union to its former state with slavery intact. In a letter to fellow abolitionist Gerrit Smith in early September, he complained about Lincoln’s decision to put Democrats in charge of key parts of the army. His response to the president’s remarks to a group of Black men who had been invited to the White House to listen to Lincoln’s views on colonization in August 1862 was caustic. Despite having been elected as an antislavery man, he charged, the president was “a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred.” Douglass chastised Lincoln for being more concerned with preserving slavery and not offending the Border States than with securing justice and humanity.

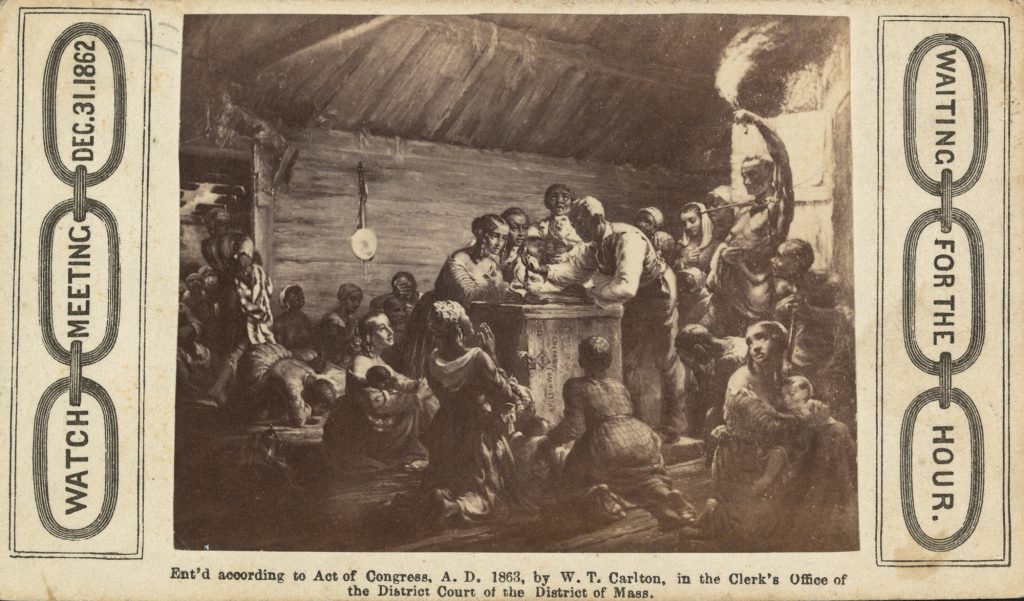

Douglass was unaware that Lincoln had already come around to his way of thinking. After failing to convince the Border States to save the Union by emancipating their enslaved laborers, Lincoln had found a way to do it himself while remaining within bounds of the Constitution. His preliminary proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862, was a final warning to the Confederate states that they had 100 days to cease their rebellion or be prepared to lose their human property.

Douglass responded to the preliminary proclamation with great optimism, certain that on January 1, 1863, the president would keep his promise if the seceded states did not return to the Union. He urged the lovers of freedom to support the president’s decision with their voices and votes. But as the weeks passed, Douglass grew concerned that Lincoln might change his mind. Opposition to emancipation was strong, as reflected in the midterm elections, which saw the Democrats gain 34 additional seats in Congress and win gubernatorial races in New Jersey and New York. Douglass now expressed dissatisfaction with the preliminary proclamation. “Emancipation is put off,” he lamented. “It was made future and conditional—not present and absolute.” Lincoln’s annual message to Congress in December 1862 did little to allay Douglass’s fears. Instead of referencing the coming proclamation, the president took the opportunity to propose a constitutional amendment that would provide compensation for any state that implemented a plan of gradual emancipation by the end of the century.

Despite Douglass’s concerns, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final proclamation. Based on military necessity, the decree promised freedom to those who were under the control of the Confederacy. Although it did not free enslaved people in the Border States, Douglass viewed it as the beginning of slavery’s demise in America. Once Virginia had been declared free, he believed, Maryland could not continue for long to deprive African Americans of their right to liberty. He was especially pleased that the proclamation authorized the use of Black men as soldiers, suggesting that through military service African Americans could secure the rights to citizenship and equality. He believed: “Once let the black man get upon his chest the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.”

Considered too old to fight (he was forty-five in 1863), Douglass committed himself to recruiting Black men for the Union army. He soon realized, however, that the promises of equality he made to those men would not be honored. Pay inequities, excessive fatigue duty, inadequate equipment, and cruel disciplinary measures convinced Douglass and the men he had recruited that the North was not serious about fair treatment. Most disturbing to him and to many Americans was the pronouncement by Jefferson Davis in December 1863 that all “negro slaves” who were captured while shouldering arms for the Union would be turned over to the states from which they came to be “dealt with according to the laws of said States.” Of course, the Confederacy labeled all Black men who were serving the Union as insurrectionists, whether they had been enslaved or free. And the laws of the states dictated that such men could be executed. At the very least, they would be sold into slavery. Douglass criticized Lincoln for failing to intervene to protect those soldiers, declaring that “no word comes from Mr. Lincoln or from the War Department, sternly assuring the Rebel Chief that inquisitions shall yet be made for innocent blood. . . If the President is ever to demand justice and humanity for black soldiers, is not this the time for him to do it?”

Eager to secure the equal treatment he had promised the men he recruited, Douglass visited the White House in the summer of 1863. Arriving without an appointment, he expected to spend a good part of the day waiting for his turn to see the president. As he related to an audience months later, he saw Lincoln ahead of many white men who had arrived before him. He recalled that as he moved toward the front of the group, they gave him disapproving looks and made insulting remarks. Once inside the president’s office, Douglass outlined his concerns to a sympathetic Lincoln, but the president counseled patience, as the American people were not yet ready to see Black men treated the same as whites. He reminded Douglass of the effort that had to be expended just to get the Black man in the fight. The rest would come later.

The man who had been so critical of Lincoln throughout the war (except when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation) carried with him from the White House the impression that the president was an honest man, sincerely devoted to the country and thoroughly determined to save it. Lincoln won over the strident abolitionist (temporarily) by treating him, in Douglass’s words, “just as you have seen one gentleman receiving another, with a hand and a voice well-balanced between a kind cordiality and a respectful reserve.” Such praise of Lincoln’s “kind cordiality” and “respectful reserve” toward a Black man was met with disdain by those who believed African Americans deserved no such courtesy. But for a man such as Douglass, who believed fervently in equality, the president’s treatment of him was obviously gratifying.

Nevertheless, Douglass continued to challenge Lincoln when the president’s views diverged from his own. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had significantly advanced the cause of freedom, but Douglass was determined to push for even greater advances. He insisted on a new social and political order that rested on equality. Lincoln’s plans for Reconstruction in the post-Civil War era were not compatible with Douglass’s vision. To ensure that Black men would be treated as full-fledged citizens, Douglass favored a more radical candidate in the 1864 presidential election. For a time, he found that person in John C. Frémont, the candidate representing the newly created Radical Democracy Party. When Frémont withdrew his candidacy and George B. McClellan won the nomination as the Democratic Party candidate, Douglass resumed his support of Lincoln.

By the summer of 1864, Douglass had acquired a reputation for radicalism that the moderate Republicans could ill afford to have on display during a presidential campaign, especially when wartime decisions had made the party’s candidate so vulnerable. Even without Douglass’s canvassing, the campaign proved to be especially messy. Reprising the race-baiting and vile arguments that characterized Stephen Douglas’s speeches in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, a Democratic- sympathizing editor and reporter of the New York World published a pamphlet on race-mixing that purported to have been written and endorsed by Republicans. The nonsensical, hoax publication claimed that Lincoln’s intent in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation was to solve the problem of prejudice in America by encouraging “miscegenation.” Citing Douglass as an advocate of this alleged agenda, the authors claimed that he had said: “We love the white man, and will remain with him . . . but we must possess with him the rights of freemen.” Curiously, a few abolitionists seemingly endorsed the pamphlet, including Douglass’s friend Theodore Tilton. Sensing a plot to discredit Republicans, Lincoln did not respond to the pamphlet’s content.

Given his forceful defense of racial equality and his biting criticism of Lincoln during most of the war, Douglass’s support in the 1864 campaign was viewed as of doubtful advantage. He represented for many inside and outside the party an America that was simply too progressive. Yet, he could not be ignored—not by the party nor by its standard-bearer. Douglass’s agitation kept the cause of freedom and equality alive and helped to place the nation on a path toward a more just future for all its people.