“Just the Wood out of which Washington Presidents are Carved”: Electing Lincoln in 1860 by Alan Guelzo

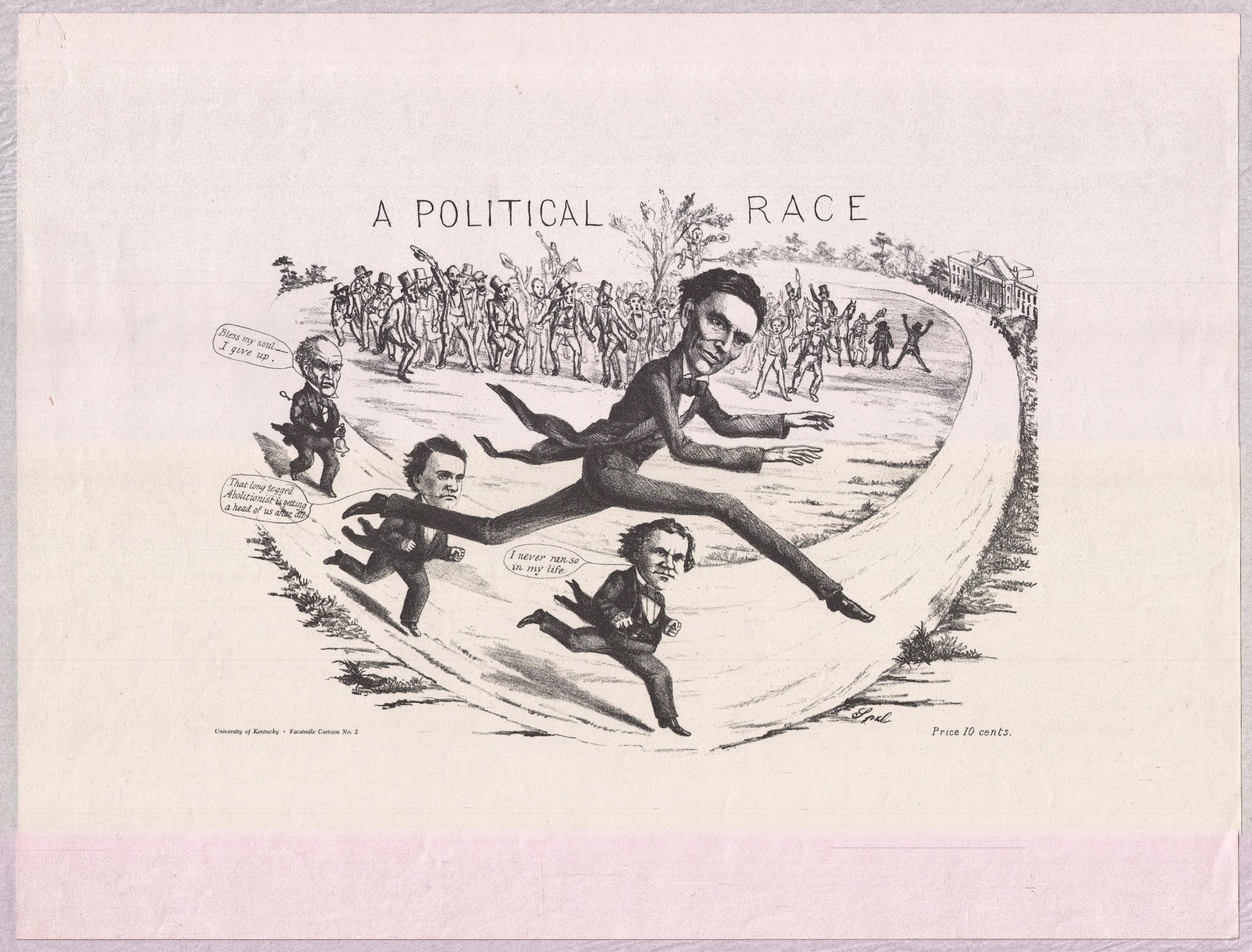

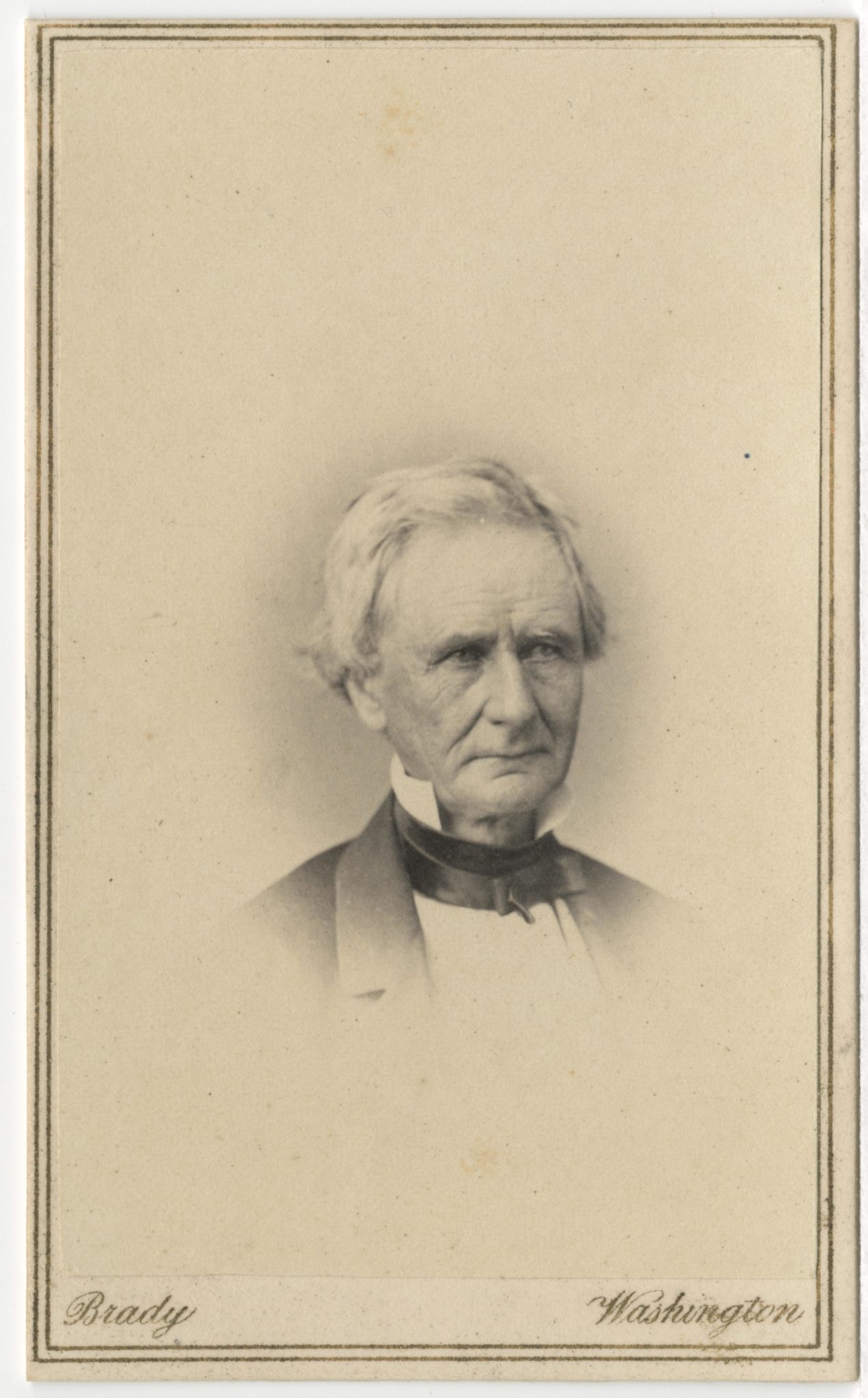

The day after Abraham Lincoln came from behind a well-populated field of potential candidates to win the Republican party’s nomination for president of the United States, an “annoyed and dejected” Thurlow Weed packed his bags and prepared “to shake the dust of the city” of Chicago “from my feet.” Weed was the long-time editor of the Albany Evening Journal and the “master-hand” behind the throne of the man Weed had assumed would have been the Republican’s obvious choice for a presidential nomination, William Henry Seward. The convention’s rejection of Seward “completely unnerved” Weed – “he even shed tears over the defeat of his old friend” – and he admitted to being so “unable to think or talk on the subject” that he planned to spend a week in Iowa, where he owned some property, before facing the necessity of returning to New York and explaining himself to Seward. But then came up the cards of David Davis and Leonard Swett, the two Illinois Republicans who had outmaneuvered Weed to secure the nomination for Lincoln. They “came to converse with me about the approaching canvass,” hoping that this “most skillful political manager” and “past master of political intrigue and stratagem” could be persuaded to put his shoulder to Lincoln’s wheel.

Weed did not hide the fact that he was “greatly disappointed” in Lincoln’s nomination. But Davis and Sweet suggested that Weed plan to return to New York through Springfield, Illinois, and meet Lincoln. The great intriguer was sufficiently intrigued to agree, and on May 24th Weed arrived in Springfield to consult with Davis, Swett and Lincoln. Weed had only met Lincoln once before, and that had been so long ago – during Lincoln’s campaign tour on behalf of Zachary Taylor’s presidency in 1848 – that Weed had entirely forgotten it. The general impression Weed had of Lincoln up til that moment was uninspiring and provincial, but the resulting conversation surprised Weed:

We entered immediately upon…the prospects of success, assuming that all or nearly all the slave States would be against us. The issues had already been made, and could neither be changed nor modified; but there was much to be considered in regard to the manner of conducting the campaign, and in relation to States that were safe without effort, to those which required attention, and to others that were sure to be vigorously contested; Viewing these questions in their various aspects, I found Mr. Lincoln sagacious and practical. He displayed throughout the conversation so much good sense, such intuitive knowledge of human nature, and such familiarity with the virtues and infirmities of politicians, that I became impressed very favorably with his fitness for the duties which he was not unlikely to be called upon to discharge.

“This conversation lasted some five hours,” Weed remembered, and ‘inspired me with confidence in his capacity and integrity.”[1]

And no wonder: perceptively boiling a case down to its most basic elements had always been Lincoln’s long suit, and together, Weed and Lincoln had shrewdly identified the three elements which would become the strategic cornerstones of the 1860 presidential campaign:

- Nearly all the slave states would be against us. Lincoln was a publicly-committed opponent of the expansion of slavery, whether into the western territories or into the Caribbean and Latin America, and as such, it took no imagination at all to realize that few voters in the slave states would be casting ballots for him, and no slave states were likely to give him a single electoral vote. But the votes of the slave states would be sharply discounted by the folly of the Democratic party, which met for its national convention in Charleston a month before the Republican convention in Chicago, and rancorously split at the seams. Northern Democrats were determined to nominate Lincoln’s one-time nemesis from the 1858 U.S. Senate race in Illinois, and the godparent of the Compromise of 1850 and the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, Stephen A. Douglas. But Douglas’s advocacy of the doctrine of ‘popular sovereignty’ in the territories was insufficient to please slave-state Democrats. They mistrusted Douglas as a man who “turns his back on his promise, repudiates his words, and tells his people that… the people of the Territories can keep slaves out.” The pro-slavery hard-liners stalked out of the Democratic national convention in protest, and nominated their own presidential candidate, Kentucky’s hero and the sitting vice-president of the United States, John C. Breckinridge, while the remainder of the nominating convention adjourned in confusion and planned for a second meeting in Baltimore.

But Breckinridge was unable to bring the old-line Whigs of Kentucky and Tennessee with him. Declaring a pox on both Democrats and Republicans, former border slave-state Whigs nominated John Bell of Tennessee as the presidential candidate of the hastily-contrived Constitutional Union party – thus siphoning-off still more slave-state voters from the national Democrats. Nor was there much likelihood that these self-divided factions would find any way to reconcile and re-join forces before election day. “At Baltimore,” warned a Democratic newspaper, “the secessionists will not be permitted to enlist and repeat their disorganizing farce.” Douglas Democrats would “yield no further capital to the sectional demagogues intent on a dissolution of the Union.” They all reminded Lincoln of

a good, sound churchman, whom we’ll call Brown, who was on a committee to erect a bridge over a very dangerous and rapid river. Architect after architect failed, and at last Brown said he had a friend named Jones who had built several bridges and could build this. ‘Let’s have him in,’ said the committee. In came Jones. ‘Can you build this bridge, sir?’ ‘Yes,’ replied Jones; ‘I could build a bridge to the infernal regions, if necessary.’ The sober committee were horrified, but when Jones retired, Brown thought it but fair to defend his friend. ‘I know Jones so well,’ said he, ‘and he is so honest a man and so good an architect that, if he states soberly and positively that he can build a bridge to Hades, why, I believe it. But I have my doubts about the abutment on the infernal side.’ So, when politicians said they could harmonize the northern and southern wings of the Democracy, why, I believed them. But I had my doubts about the abutment on the southern side.[2]

Lincoln might not get any votes from any of the slave states; but the votes he didn’t get would be squandered among three candidates – Douglas, Breckinridge and Bell – without subtracting any free-state votes from the Republicans. The New York Herald lamented that if the Democratic split persisted “in this fashion to the end of the chapter,” then “the election of Lincoln is as certain as that tomorrow’s sun will rise.”[3]

- The issues had already been made. For the second time in its existence, the Republican national platform had published its opposition to giving “legal existence to slavery in any territory of the United States,” even as it affirmed “inviolate…the right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively.”[4] What was more, Lincoln was on public record, as far back as the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 and even more obviously during the remarkable race he had run against Douglas for the U.S. Senate in 1858, as fully in harmony with that platform. There would be no catastrophic mid-course pivots, like Henry Clay’s on the Texas issue in 1844, or Winfield Scott’s clumsy appeal to immigrants voters and the “Irish brogue” he claimed to have “heard… before on many battle fields” – although presumably not at the battle of Chapultepec, where thirty Irish ‘San Patricios’ were hanged as deserters on Scott’s order.[5]

- There was much to be considered…in relation to the States that were safe without effort, to those which required attention, and to others that were sure to be vigorously contested. The time had long past when the slave states, simply by their popular majorities, could count on those majorities translating easily into majorities in the Electoral College. The population of the free states had increased by 72% since 1830, from 6.9 million (out of 12.8 million nationally) to 18.5 million, while the slave states’ populations had increased by 65%, or only 11 million. In 1830, this had been enough to ensure that the twelve slave states would cast 118 of the 286 electoral votes (or 41%) and would only need Democratic majorities in one or two Northern states to ensure victory. In 1860, the shoe was on the other foot, “the South…relatively diminishing in prestige and strength in the Union.” The slave-state portion of the electoral pie had slipped to 35% and would command only 120 of the 303 total electoral votes at stake, while the free states would command 183. Victory would require only 152. Assuming that they would hold the states which had gone for Frémont in 1856, and that Lincoln’s presence at the head of the ticket would guarantee Illinois’s 11 electoral votes, then all Republicans had to do was to ensure that New York (with 35 electoral votes) and either Pennsylvania (with 27) or Ohio (with 23) went their way, and the election would be over.[6]

For Lincoln’s part, the new Republican nominee was vastly relieved by Weed’s visit. “Weed was here,” Lincoln told Illinois’s Republican senator Lyman Trumbull, “and saw me; but he showed no signs whatever of the intriguer. He asked for nothing; and said N.Y. is safe.” By the end of June, Lincoln’s election already began to appear inevitable. “The prospect of Republican success now appears very flattering, so far as I can perceive,” Lincoln wrote to his vice-presidential running-mate, Hannibal Hamlin. “It looks as if the Chicago ticket will be elected,” he wrote to Anson Henry on the Fourth of July. His early backer, Charles Ray of the Chicago Tribune, began urging him “to consider what shall be the quality and cut of your inaugural suit.” Even Mary Lincoln “feels quite confident of her husband’s election,” and Robert Lincoln was being sarcastically christened as “the Prince of Rails.”[7]

The icing on the electoral cake was spread from a factor which might have been an embarrassment for an old politico like Thurlow Weed to have raised with Lincoln, but which turned out to be as much an asset for Lincoln as all the others: honesty. As if the divisive dispute over how perfectly pro-slavery the Democratic candidates could make themselves, the outgoing Democratic administration of James Buchanan managed to taint them with one more liability, and that was the stench of official corruption. Isaac Toucey, Buchanan’s secretary of the Navy, was denounced for rigging bids on Navy contracts in order to steer them to a single contractor, W.C.N. Swift of New Bedford, Massachusetts, who just happened to have been a major contributor to Buchanan’s 1856 presidential campaign; New York City postmaster Isaac Vanderbeck Fowler absconded after being indicted for embezzling $155,000; one of secretary of war John B. Floyd’s relatives by marriage, Godard Bailey, skimmed $870,000 from an annuity fund established as part of government treaties with Indian tribes, all the while working as a clerk in the Interior department. Buchanan naively persisted in speaking of Toucey as “a gentleman of the old school, full of principle and honor,” but otherwise, Toucey, Floyd and Fowler all stank in the nostrils of the country. It was inevitable that the Republican campaign would make “frugal government and honest administration…not less vital” an issue than “aggressive, all-grasping Slavery propagandism,” and just as inevitable that “Abraham Lincoln will receive thousands of votes that never were Republican before.”[8]

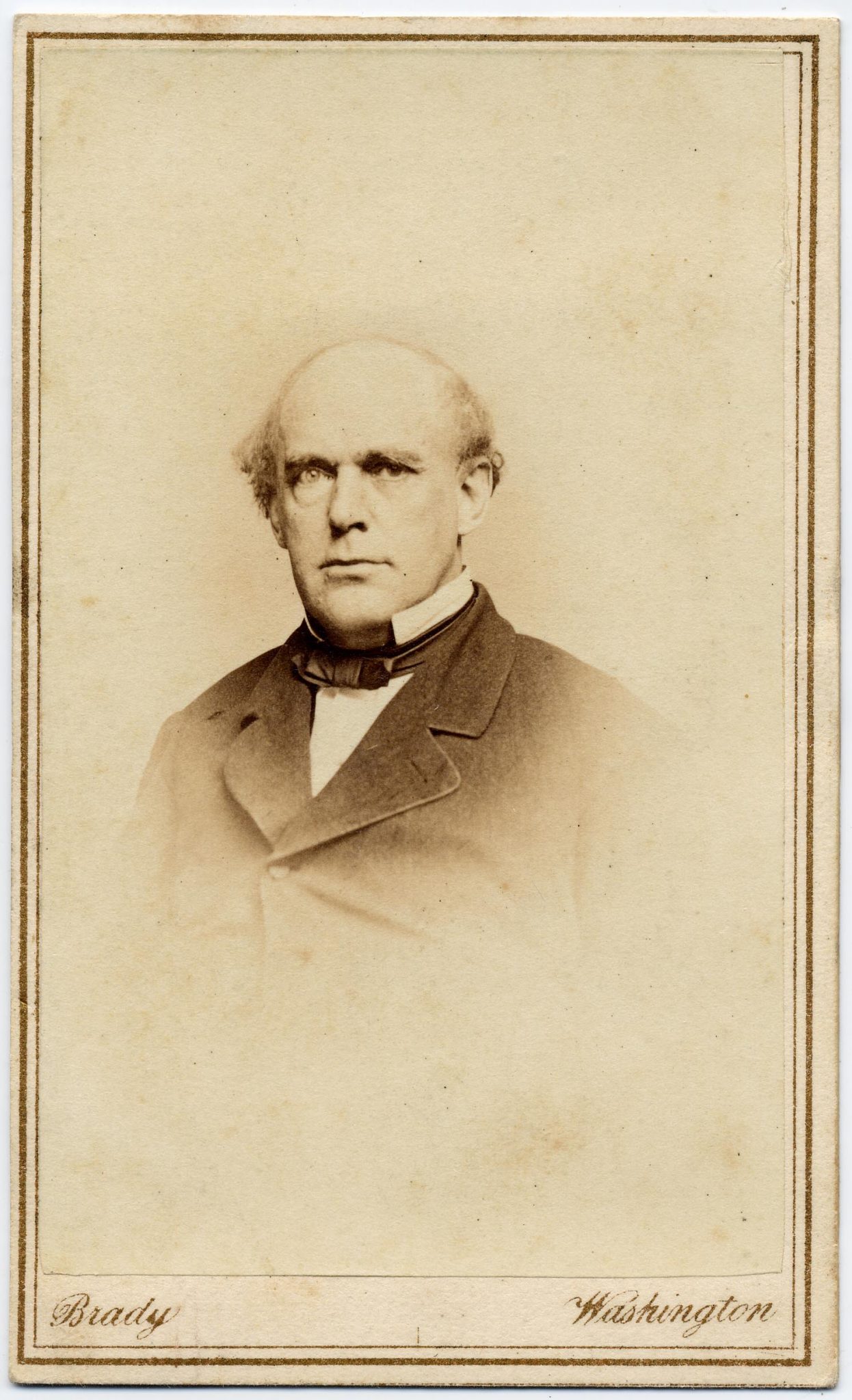

Nevertheless, electing Lincoln was not going to be done without some hard political work. Lincoln’s first major task was to secure the loyalty of the candidates he had elbowed aside, and their followers. That would involve placating New Yorkers (starting with Thurlow Weed) who had expected Seward to be the nominee, Ohioans who had backed Ohio U.S. senator Salmon P. Chase, and Pennsylvanians who had hoped against hope for their own favorite son, Simon Cameron. If they chose to sulk in their tents and Lincoln lost those states to Democrats, the whittling-away in the Electoral College might lower the Republican electoral vote-count to the point where the election would end up in the House of Representatives, as it had in the disastrous election of 1824. “The speeches of Cameron and the Blairs are singularly cold,” smirked the New York Herald, “while in this State the Seward men act as if they desired to encompass Lincoln’s defeat.” Two days after meeting Weed, Lincoln went to work on Salmon Chase, appealing to the stiff-necked Ohioan who had earned the reputation of being ‘the attorney general of fugitive slaves’ for his famous defense in that to join “those distinguished and able men” who “already in high position to do service in the common cause.” On June 18th, he turned to securing the German vote by assuring the prominent German Republican, the émigré Carl Schurz, that despite “your having supported Gov. Seward, in preference to myself in the convention, is not even remembered by me for any practical purpose…. I go not back of the convention, to make distinctions among its members.” [9]

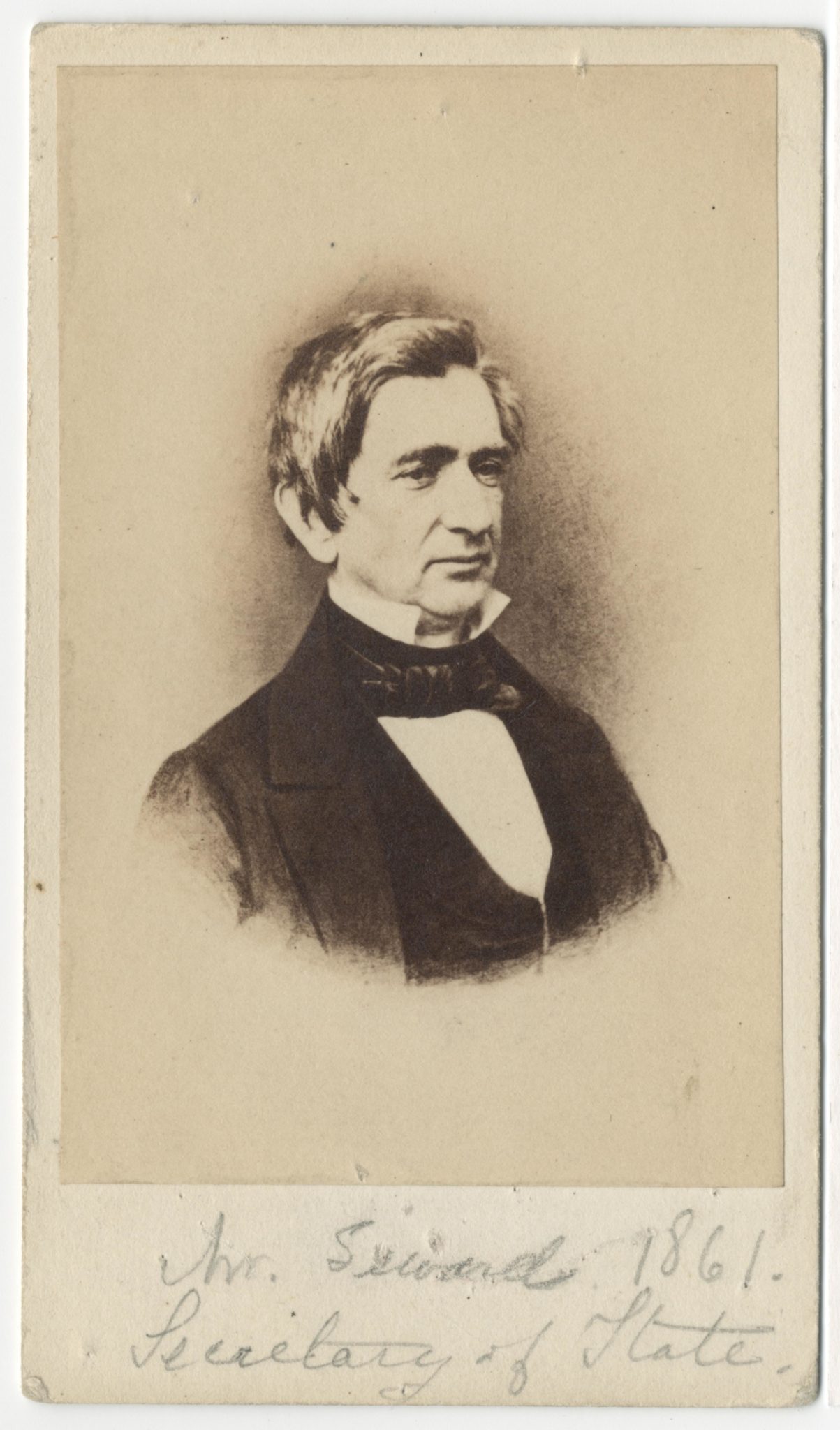

Pacifying Seward, however, would require more than a friendly chat with Thurlow Weed. The ambitious and melodramatic U.S. senator from New York had made no secret of his expectation of becoming the 1860 Republican nominee, and when the word came that the convention had gone for Lincoln instead, Seward was almost inconsolable. If he had been keeping a diary, he later told Charles Francis Adams, it would have been filled “with all my cursing and swearing on the 19th of May last.” He gallantly replied to a letter from the Republican National Committee with the promise that he would give the party “a sincere and earnest support.” But to his wife, he confided that he dreaded his return to the Senate, since he would now appear there as “a leader deposed by my own party, in the hour of organization for decisive battle.” Lincoln gingerly suggested to Seward that they meet, although the suggestion specified that Seward come to Springfield, not Lincoln to Auburn, New York. This, Seward agreed to do, but the meeting would end-up being included as a stop on a speaking tour Seward would undertake in the fall. That way, neither Republican would be seen as coming cap-in-hand to the other.[10]

Even so, Seward showed little eagerness to endorse Lincoln. Along his route, Seward praised Lincoln as the Republicans’ “great and glorious leader,” He stopped “in Springfield scarcely fifteen minutes, and for about ten of those fifteen was engaged in talking to the crowd, and for the other five in introducing his traveling party to the President-to-be, with whom he at no time conversed unheard by at least a dozen listeners.” He pledged that “the State of New York will give a generous, cheerful and effective support to your neighbor, Abraham Lincoln,” but he pulled shy of making any personal pledges. Seward could not entirely conceal the “disfavor, if not…contempt” he felt for “a man who, without any special merit of his own, was taken from the subordinate ranks of the party and promoted over his head.”[11]

If appeals to party loyalty were not enough balm to heal disappointed Republican souls, patronage might be. In an era before the professionalization of the civil service, the president had complete hire-and-fire authority over every government job in the executive branch, from the cabinet down to the lowliest postmaster. Patronage was the glue that held the political parties together, and these appointments were understood frankly as the principal method of rewarding faithful political service. Altogether, 1639 government appointments were within Lincoln’s direct gift, and he would make the most of them, dumping 1479 incumbents from the Buchanan administration; and even wider net of patronage appointments fanned-out indirectly from the Post Office and the Treasury Department, including 33,000 postmasters and clerks 4500 mail agents and contractors, 2,800 customs agents. Unwilling to jeopardize his “honest Abe” image, Lincoln insisted that patronage in a Lincoln administration would be fairly divided. Lincoln announced that he “neither is nor will be, in advance of the election, committed to any man, clique, or faction.” The “part of duty, and wisdom” is “to deal fairly with all. He thinks he will need the assistance of all; and that, even if he had friends to reward, or enemies to punish, as he has not, he could not afford to dispense with the best talent, nor to outrage the popular will in any locality.”[12]

However, lofty declarations of impartiality had never before stood in the path of self-interest rightly-understood, nor did they in this case. Salmon Chase would get the nod as Secretary of the Treasury, Simon Cameron would become Secretary of War, and Seward would move-in as Secretary of State. The next tier of appointments would be carefully divided between the partisans of Chase, Cameron and Seward. Abram Wakeman, a prominent ally of Thurlow Weed, would get the lucrative appointment as Postmaster of New York City; Cameron’s brother James would win a commission as colonel of the 79th New York, while his son Brua would become a military paymaster; Hiram Barney, an ally of Chase, would win the even-more-lucrative post of Collector for the Port of New York, and Chase’s brother, Edward, would become U.S. marshal for the Northern District of New York.[13]

Lincoln made no similar attempt to appease unhappy Democrats, and it probably wouldn’t have been worth it if he’d tried. The Breckinridge Democrats might have loathed Stephen A. Douglas, but they regarded Lincoln as a “Black Republican” who had “openly proclaimed a war of extermination against the leading institutions of the Southern States.” The fire-eating Charleston Mercury described Lincoln as a “horrid-looking wretch…sooty and scoundrelly in aspect; a cross between the nutmeg dealer, the horse-swapper, and the nightman.” A Georgia satirist pilloried Lincoln in rhyme:

His cheekbones were high and his visage was rough,

Like a middling of bacon, all wrinkled and tough;

His nose was as long, and as ugly and big

As the snout of a half-starved Illinois pig;

He was long in the legs and long in the face,

A Longfellow born of a long-legged race….[14]

But Northern Democrats, even as they gritted their teeth at the prospect of Douglas’s defeat, were no more inclined than their Southern counterparts to countenance a Lincoln presidency. They had not forgotten the stark, moralistic terms in which Lincoln had cast opposition to slavery in his debates with Douglas in 1858 and in the Cooper Union speech earlier that year. The New York Herald took the lead, denouncing the Republicans as “saturated with abolitionism of the most rabid kind” and Lincoln “as an extreme abolitionist of the revolutionary type” who would “liberate all the slaves in the Southern States by habeas corpus, using the whole power of the army and navy in carrying out his grand scheme.” New York Democrat Samuel J. Tilden warned Gotham Democrats, “Elect Lincoln, and we invite those perils which we cannot measure… Defeat Lincoln, and all our great interests and hopes are, unquestionably, safe.” August Belmont, New York’s Democratic financial wizard, feared that “the election of Mr. Lincoln to the Presidential chair must prove the forerunner of a dissolution of this Confederacy amid all the horrors of civil strife and bloodshed.” In Indiana, the Douglas Democrats exhorted the “Freemen of Indiana” not even to think of voting “for this man, Lincoln–a genus of the same type as the traitor, John Brown, who was hung at Charleston; an abolitionist of the reddest dye; and a wholesale disunionist!” Ohio’s Clement Vallandigham was horrified that a divided Democratic party would lead to the election of a president “as revolutionary, disorganizing, subversive of the Government” as Lincoln.[15]

By the same token, Lincoln made no gestures in the other direction, either, toward the absolute, no-concession abolitionists. Wendell Phillips, for whom nothing less than immediate and unconditional abolition was acceptable, attacked Lincoln’s concentration solely on limiting the spread of slavery for making him nothing more than a “constitutional slave-hound.” Lincoln was

ready to hunt slaves so long as the Union, the party, and the white race seem to need it; and he is therefore just the wood out of which Washington Presidents are carved. If any think such characters useful and necessary now-a-days, let them. But that is no reason why I should call such persons honest men, any more than I should call geese eagles, because a goose once saved Rome.

Radical abolitionists held their own presidential nominating convention on August 29th in Syracuse, New York, adamantly refusing to vote “for a candidate like Abraham Lincoln, who stands ready to execute the accursed Fugitive Slave Law, to suppress insurrections among slaves, to admit new slave States, and to support the ostracism, socially and politically, of the black man of the North” and nominating the veteran abolitionist Gerrit Smith. Abolitionists even argued among themselves over Lincoln: when Scottish-born abolitionist James Redpath announced after the Republican convention that “he should vote for Lincoln” because it “would benefit the slave,” this former ally of John Brown was roundly pummelled by the come-outer abolitionist, Stephen S. Foster, who was “astounded that such a man as Redpath should declare his willingness to vote for a man like Lincoln, who declared his willingness to be slave-driver general.”[16]

Lincoln put less labor into reaching-out to Northern Democrats or radical Abolitionists, and more into fending-off efforts by others to put words into his mouth. “I would cheerfully answer your questions in regard to the Fugitive Slave law, were it not that I consider it would be both imprudent, and contrary to the reasonable expectation of friends for me to write, or speak anything upon doctrinal points now. Besides this, my published speeches contain nearly all I could willingly say. Justice and fairness to all, is the utmost I have said, or will say,” he replied in August to an over-curious New York abolitionist (with the ominous name of T. Apolion Cheney). He was still repeating that formula in October: “Those who will not read, or heed, what I have already publicly said, would not read, or heed, a repetition of it,” Lincoln replied, adding with a Biblical flourish which featured one Abraham quoting another Abraham, “’If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded though one rose from the dead.’” The governor of Illinois, John Wood, offered Lincoln space in the old State Capitol as an office, and shortly after Weed’s visit to Springfield, Lincoln hired John G. Nicolay, who clerked for Lincoln’s friend and the Illinois secretary of state, Ozias Hatch. He prepared for Nicolay a form letter stating that friends had beseeched him “to write nothing whatever upon any point of political doctrine. They say his positions were well known when he was nominated, and that he must not now embarrass the canvass by undertaking to shift or modify them.”[17]

This was an unusually shut-mouthed strategy for a man whose rhetorical powers against Douglas in 1858 had boosted him into the national limelight. But Lincoln was acting on orders from the Republican National Committee, who could see the prize dropping effortlessly into their hands and who wanted to do nothing to interfere with it.

“I have observed that those candidates who are most cautious of making pledges, stating opinions or entering into arrangements of any sort for the future save themselves and their friends a great deal of trouble and have the best chance of success,” advised William Cullen Bryant, “Make no speeches write no letters as a candidate, enter into no pledges, make no promises, nor even give any of those kind words which men are apt to interpret into promises.” All Lincoln needed to do was “do nothing at present but allow yourself to be elected.” Even when he was invited to speak at a national horse-show in the presumably friendly environs of Springfield, Massachusetts, in August, George Fogg, the secretary of the Republican National Committee, nixed the idea. “I answer very frankly that I do not think it would ‘help,’” Fogg wrote, “Everything east I believe is well. The election is ours now. The triumph is ours.” And Lincoln stayed put in his own Springfield. When the Illinois Republican state convention met in Springfield on August 8th, Lincoln addressed a crowd that jammed around his doorway and sidewalk , his “remarks” amounted to 268 carefully-opaque words. “It has been my purpose, since I have been placed in my present position, to make no speeches,” Lincoln said, “I appear upon the ground here at this time only for the purpose of affording myself the best opportunity of seeing you, and enabling you to see me.”[18]

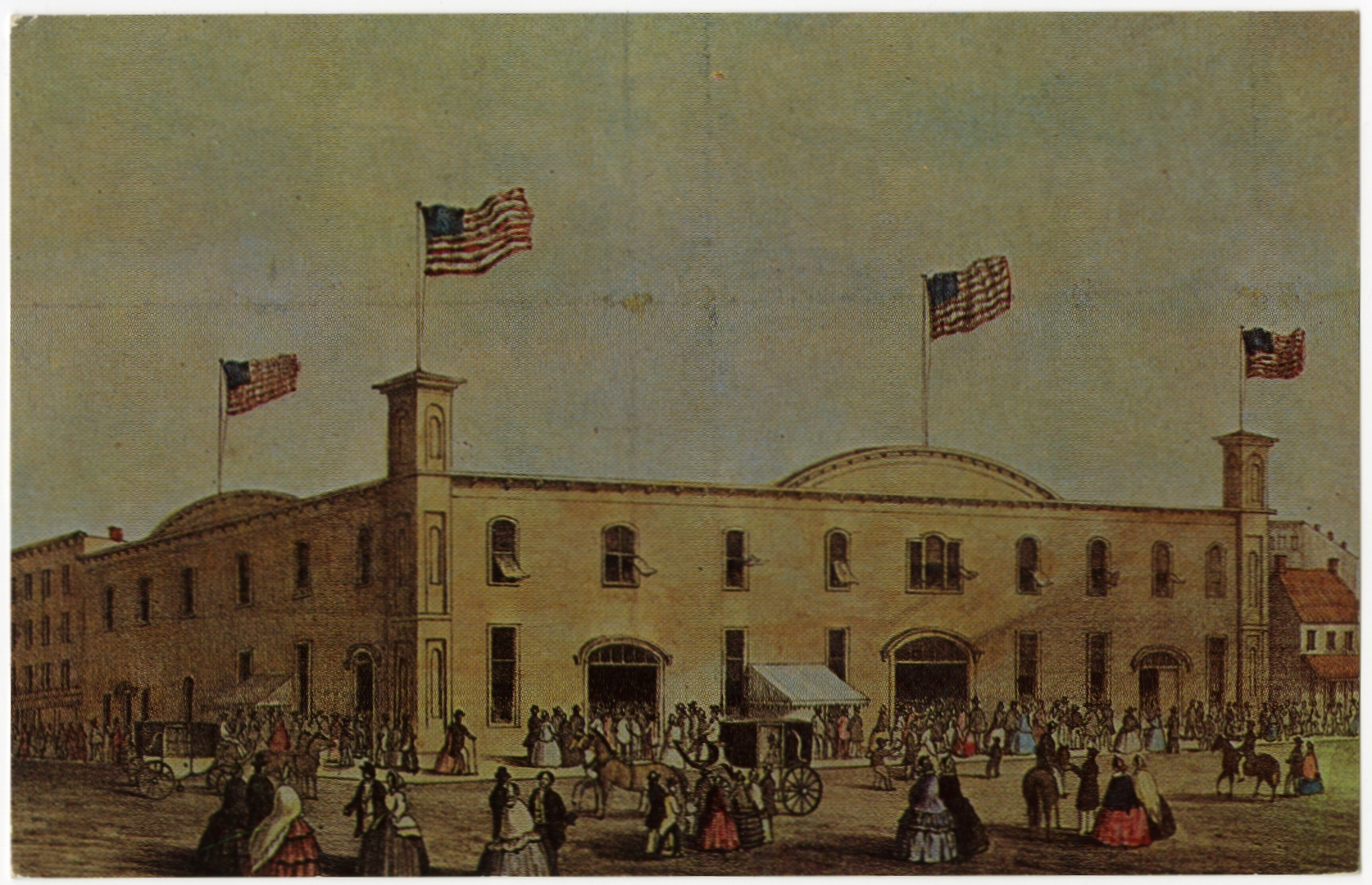

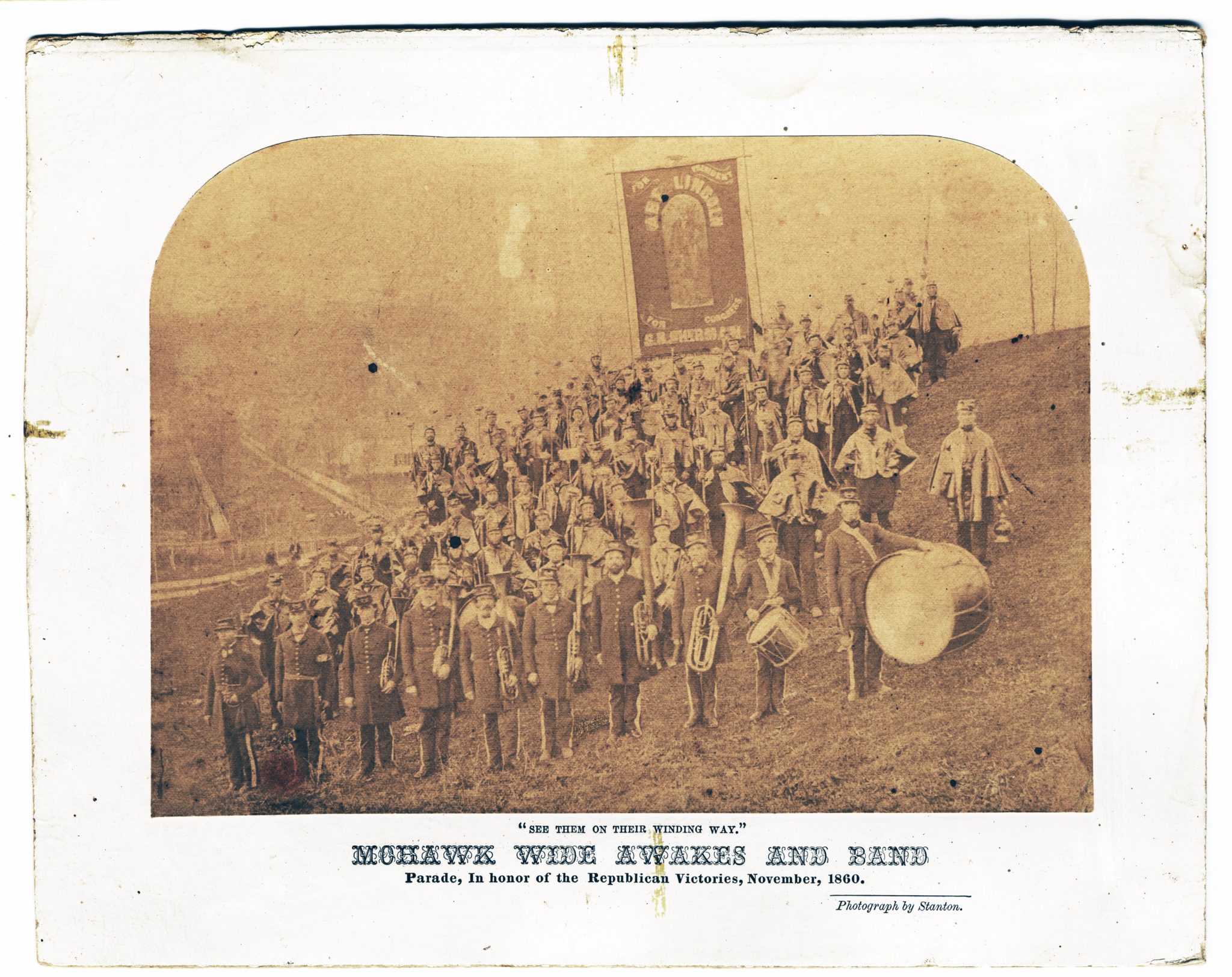

Lincoln needn’t have worried that this silent campaign would damage his prospects. Although he remained in Springfield, he sent a variety of emissaries on personal embassies to represent him and garner responses. The Republican National Committee did more than its share of work in crafting a national image of a moderate, incorruptible and (with some degree of fudging) substantially less homely candidate whom anyone upset with insider politics and slaveholder arrogance could support. Fourteen campaign biographies were written and circulated; artists and photographers were commissioned to capture (and improve) Lincoln’s likeness for mass distribution; and even one sculptor was hired to prepare campaign statuettes. Lincoln might refuse to make public appearances, but the national committee ensured that Republican organizers made the campaign dramatically visible through campaign newspapers, Lincoln clubs, and torchlight parades by Republican “Wide-Awakes.”[19]

The Wide-Awakes provide a dash of unusual electioneering color to the campaign of 1860. But they often disguise how calculating the Republicans were in snagging the attention and commitment of younger, first-time voters through groups like the Wide-Awakes and “Young Republican” clubs. The Young Men’s Republican Union of New York City “circulated 3,961,000 pages of Republican documents,” and the New-York Tribune estimated that “the number of speeches made during the…campaign has been quite equal to that of all that were made in the previous Presidential canvasses from 1789 to 1859 inclusive. We estimate that not less than ten thousand set speeches have been made in this State alone, and probably not less than fifty thousand within the limits of the Union.” In Portland, Maine, an “evening torchlight procession” of Wide-Awakes “wore glazed black caps and cloaks, and presented a particularly somber appearance as they glided along beneath the glimmering flashes of their flambeaux,” while “the Lincoln guard wore red glazed cloaks” and marched to the music of “a great number of bands.” In New York City, five different Republican clubs – including the “Irrepressible Wide Awake Battalion” and the “Republican Association of the 19th Ward” held meetings. Across the North, recalled Charles Francis Adams,

The campaign of 1860 was essentially a midnight demonstration— it was the “Wide-awake” canvass of rockets, illuminations and torch-light processions. Every night was marked by its tumult, shouting, marching and countermarching, the reverberation of explosives and the rush of rockets and Roman candles. The future was reflected on the skies. …We knew nothing of the South, had no realizing sense of the intensity of feeling which there prevailed; we fully believed it would all end in gasconade.[20]

Election days in the 19th century did not follow a synchronized schedule. Presidential votes were cast across the nation on November 6th, but a series of state legislative, gubernatorial, and Congressional elections were being held in Maine, Ohio and Pennsylvania beginning in September, and acted as a bellwether for the direction of the November voting. On that basis alone, the Republican confidence in an electoral sweep was more than borne-out:

- Republicans swept the six Congressional districts of Maine on September 10th and elected a Republican governor, 69,000 to 51,000

- Pennsylvanians, who voted a month later, elected a Republican, Andrew Curtin, as governor by a 32,000-vote margin, gave crushing majorities to Republicans in the state legislature, and elected Republicans in twenty of their twenty-five Congressional districts

- Ohio elected a Republican state Supreme Court judge and handed thirteen of its 21 Congressional seats to Republicans; overall, Republican votes overwhelmed Democrats with 53% of all votes cast.[21]

Lincoln was delighted with the “late splendid victories…which seem to foreshadow the certain success of the Republican cause in November.”[22] Which, of course, they did. On November 6, Lincoln carried the popular vote of all eighteen of the free states, including Oregon and California, which in turn, easily gave him 180 electoral votes – twenty-eight more than needed. No Lincoln votes were counted at all in nine Southern states (although this was better than Frémont’s no-shows in 1856, when twelve states registered no Republican votes), but they hardly mattered. John C. Breckinridge won eleven slave states, but this garnered him only 72 electoral votes. Douglas did much better in the popular vote, outdistancing Breckinridge by 61%. But Douglas still lagged far behind Lincoln – by almost half –a-million votes); moreover, the Douglas votes were so scattered across the country that they earned him only twelve electoral votes, placing him behind not only Breckinridge but even the faded John Bell. Lincoln won only 39.8% of the overall popular vote; but he did it in concentrations big enough to win him an easy majority in the Electoral College.

Only in California, where a change of 700 votes could have given the state to a Democrat, was the election even close, and California had only four electoral votes to contribute. In the states where Lincoln won, he mostly won by unchallengeable majorities: 57% in Connecticut, 58% in New York, 56.5% in Pennsylvania, 52% in Ohio, 57% in Michigan. Although it has often been a parlor-game to wonder whether the change of one or another state’s votes might have thrown the election into the House of Representatives, in the states which really mattered (like New York), Lincoln’s popular majority was so great as to be unassailable, even if the Democratic and Constitutional Union candidates had forgotten their differences and made a common front. Besides, Douglas himself had pledged that “the election shall never go into the House; before it shall go into the House, I will throw it over to Lincoln.”[23]

“The contest has been so long and so exhaustive,” wrote John Nicolay after the election frenzy had worn off, that in Lincoln’s Springfield, the “people look and act as if they were almost too tired to feel at all interested in getting up a grand hurrah over the victory.” At least, Nicolay reflected, the long struggle to contain slavery was over. “I myself can hardly realize that after having fought this Slavery question for six years past,…I am rejoicing at a triumph which…we hardly dared dream about.” Salmon Chase agreed: “The great object of my wishes & labors for nineteen years is accomplished in the overthrow of the Slave Power,” Chase wrote to Lincoln that day after the election. Lincoln hoped the same realization would prevail in the South, and ensure a peaceful inauguration five months hence. “The prevalent apprehensions, a week or two ago, of our lords of trade, that the People of the Southern States would insist on going naked in case of Lincoln’s election,” smirked the New-York Tribune, “have already been measurably dissipated.” Even “Mr. Lincoln considers the feeling at the South to be limited to a very small number.” They were, all of them, wrong. On the same day, the South Carolina legislature voted unanimously to schedule elections on December 6th for a state secession convention. A very different future was about to break upon the nation, but, as Charles Francis Adams wrote, “of the tremendous nature of that future, we then had no conception. We all dwelt in a fool’s Paradise.”[24]

[Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of the Civil War Era Studies Program at Gettysburg College.]

Endnotes

[1] Autobiography of Thurlow Weed, ed. Harriet Weed (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1884), 1:602 and 2:271; Hudson C. Tanner, “The Lobby,” and Public Men from Thurlow Weed’s Time (Albany, NY: George MacDonald, 1888), 408; The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz, eds. Agathe, Marianne & Carl Lincoln Schurz (London: John Murray, 1909), 2:177.

[2] Horace Greeley and John F. Cleveland, A Political Text-Book for 1860: Comprising a Brief View of Presidential Nominations and Elections (New York: Tribune Association, 1860). 196; “Anecdote of President Lincoln,” in Frank Moore, ed., Anecdotes, Poetry, and Incidents of the War: North and South, 1860-1865 (New York: Boston Stereotype, 1866), 32; Douglas R. Egerton, Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election That Brought On the Civil War (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010), 154.

[3] “Reply of Douglas to Breckinridge,” New York Herald (September 8, 1860).

[4] “National Platforms of 1860,” in The Political History of the United States of America, During the Period of Reconstruction, ed. Edward McPherson (Washington: Philp & Solomon, 1871), 629.

[5] Robert V. Remini, Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (New York: Norton, 1991), 638-39; Timothy D. Johnson, Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 215.

[6] “Population of Regions, by Sex, Race, Residence, and Nativity, 1790 to 1970,” in Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975), 1:22-37; Python, “The Secession of the South,” DeBow’s Review 28 (Octiober 1860), 358; Anthony Trollope, North America (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1862), 3:85; Leonard Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 192; Michael Green, Lincoln and the Election of 1860 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2011), 91; Egerton, Year of Meteors, 113, 210.

[7] Lincoln to Trumbull (June 5, 1860), to Hamlin (July 18, 1860) and to Henry (July 4, 1860), in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4:71; Mercy Levering Conkling to Clinton Conkling (October 20, 1860), in Concerning Mr. Lincoln: In Which Abraham Lincoln Is Pictured As He Appeared to Letter Writers of His Time, ed. Harry Pratt (Springfield, IL: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1944), 25; Ray to Lincoln (June 27, 1860), in The Lincoln Papers, ed. David Mearns (New York: Doubleday, 1948), 1:262

[8] Mark W. Summers, The Plundering Generation: Corruption and the Crisis of the Union, 1849-1861 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 241; “Injunction Against the Bank of the Republic; United States Circuit Court, Dec. 26 Before Judge Smalley,” New York Times (December 27, 1860); Buchanan to Dr. Blake (November 21, 1864), in George Ticknor Curtis, Life of James Buchanan, Fifteenth President of the United States (New York: Harper & Bros., 1883), 2:629; David E. Meerse, “Buchanan, Corruption, and the Election of 1860,” Civil War History 12 (June 1966), 118, 122; “Springfield Correspondence,” (May 21, 1860), in Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998), 3; Michael F. Holt, The Election of 1860: “A Campaign Fraught with Consequences” (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 113.

[9] Lincoln to Chase (May 26, 1860), to Schurz (June 18, 1860), in CW, 4:53, 78; “The Presidential Election—Present Aspect of the Canvass,” New York Herald (May 29, 1860).

[10] Charles Francis Adams, 1835-1915: An Autobiography (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916), 69; Seward to George Ashmun (May 21, 1860) and Frances Seward (May 30, 1860), in Frederick W. Seward, Seward at Washington, as Senator and Secretary of State (New York: Derby and Miller, 1891), 1:454.

[11] Charles Francis Adams, jnr., “Gov. Seward’s Tour,” New York Times (October 6, 1860); “Seward’s Speech at Lincoln’s Home,” Chicago Tribune (October 3, 1860); “The Second American Revolution” and “The Abolition Programme for Lincoln’s Administration,” New York Herald (October 18, 1860).

[12] Carl Russell Fish, The Civil Service and the Patronage (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1904), 170; Register of Officers and Agents, Civil, Military and Naval, in the Service of the United States on the Thirtieth September, 1863 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 1-2, 40-41, 57-96, 97, 122, 125, 265; Paul P. Van Riper and Keith A. Sutherland, “The Northern Civil Service, 1861-1865,” Civil War History 11 (December 1965), 347; Lincoln to David Davis (May 26, 1860), in CW, 1st Supplement, 54.

[13] “Memorandum: New York Appointments” (April 15, 1861), in CW, 4:334; Erwin Stanley Bradley, Simon Cameron, Lincoln’s Secretary of War: A Political Biography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 180.

[14] Steven A. Channing, Crisis of Fear: Secession in South Carolina (New York: Norton, 1974), 231; Emerson David Fite, The Presidential Campaign of 1860 (New York: Macmillan, 1911), 210; E.P. Birch. “The Devil’s Visit to ‘Old Abe,’” in The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, ed. Frank Moore (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1862), 3:68.

[15] “Lincoln’s Radicalism Proved—His Obedience to the Abolition Idea” and “What is the Political Stripe of ‘Honest Abe’ Lincoln?” New York Herald (September 6, 1860 and May 30, 1860); Russell McClintock, Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 34; David Black, The King of Fifth Avenue: The Fortunes of August Belmont (New York: Doubleday, 1981), 199; “Come, Let Us Reason Together,” Vincennes Weekly Western Sun (September 1, 1860); James Laird Vallandigham, A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham (Baltimore: Turnbull Bros., 1872), 139.

[16] “Lincoln and Slavery–Conservatism of the Republican Candidate,” New York Times (September 4, 1860); “Wendell Phillips’ Estimate of Lincoln,” New York Times (September 7, 1860); “Radical Abolition Convention,” The Liberator (September 7, 1860); “Political Anti-Slavery Convention,” National Anti-Slavery Standard (June 9, 1860).

[17] Lincoln to Cheney (August 14, 1860) and William Speer (October 23, 1860), and “Form Reply to requests for Political Opinions” (June 1860), in CW 4:60, 93, 130; Wood to Lincoln (May 22, 1860), in The Lincoln Papers, ed. Mearns, 1:248.

[18] Bryant to Lincoln (June 16, 1860) and Fogg to Lincoln (August 18,1860), in The Lincoln Papers, ed. Mearns, 1:257-58, 273; “Remarks at a Republican Rally, Springfield, Illinois (August 8, 1860), in CW, 4:91; “Springfield Correspondence” (August 9, 1860), in Lincoln’s Journalist, 3-6; Paul Angle, “Here I Have Lived”: A History of Lincoln’s Springfield, 1821-1865 (Springfield, IL” Abraham Lincoln Association, 1935), 246-48.

[19] Green, Election of 1860, 83; Thomas Horrocks, Lincoln’s Campaign Biographies (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2014), 46-70.

[20] Holt, The Election of 1860, 140; “The Canvass,” New-York Daily Tribune (November 8, 1860); John D. Stewart, “The Great Winnebago Chieftain: Simon Cameron’s Rise to Power, 1860-1867,” Pennsylvania History 39 (January 1972), 27; Alban Jasper Conant, “A Portrait Painter’s Reminiscences of Lincoln,” McClure’s Magazine 32 (March 1909): 515. “Our Augusta Correspondence,” New York Herald (September 8, 1860); Fite, The Presidential Campaign of 1860, 227; Adams, An Autobiography, 69; John W. Vinson, “Personal Reminiscences of Mr. Lincoln,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 8 (January 1916), 574.

[21] The Tribune Almanac for 1861 (New York, 1861), 39, 47-48, 59-60; Jerry R. Desmond, “Maine and the Elections of 1860,” New England Quarterly 67 (September 1994), 465.

[22] Lincoln to John Read (October 13, 1860), in CW 4:127.

[23] Tribune Almanac for 1861, 64; Green, Election of 1860, 91-93; Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973), 802.

[24] Nicolay to Therena Bates (November 11, 1860), in With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, ed. Michael Burlingame (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 9-10; Chase to Lincoln (November 7, 1860), in The Lincoln Papers, ed. Mearns, 1:302; “Trade and Politics” and “Highly Interesting from Springfield,” New-York Daily Tribune (November 10, 1860); Adams, An Autobiography, 69; Shearer Bowman Davis, At the Precipice: Americans North and South During the Secession Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 74-75.