Interview with Brian Dirck

An Interview with Brian Dirck about his new book, The Black Heavens: Abraham Lincoln and Death (Southern Illinois University Press, 2019)

Sara Gabbard: You undertook a monumental task in writing on this subject. What led you to accept the challenge?

BD: Well, “The Black Heavens” could almost be a case study in how books sometimes evolve beyond their original purpose, and how asking questions leads in turn to asking other questions, and then still other questions, until the result is a very different book.

The project was originally titled “Lincoln’s Hardest Summer,” and was to be a case study of Lincoln’s leadership during that last, brutal summer of 1864, when the president had to guide the Union through the trauma of the Wilderness and Georgia campaigns, the problems of emancipation and political revolts within his own party, all while facing re-election. I was interested in the interplay between democracy, presidential leadership and war.

As I delved more deeply, it became clear that the real question was, how did Lincoln get the country to accept such astronomically high casualty rates and still maintain the war effort—not to mention re-elect him and guarantee more war? This led naturally to the next question: so what then did Lincoln think of all those battle deaths, a question that then led to, “well, what exactly did he think about death generally?”

It was an intriguing question; but when I began looking at the literature on Lincoln, I was surprised at how little has actually been written about what seems like such a basic question. Various authors here and there discuss Lincoln’s reactions to the deaths of soldiers, his loved ones, etc., but hardly anyone (other than Robert V. Bruce) has done much by way of just focusing on his understanding of death, carrying that thread of his reaction to death and mourning from his early life through his presidency.

Almost as surprising is the fact that the growing literature on death and the Civil War tends to ignore Lincoln. I’m thinking here of course of Drew Gilpin Faust’s seminal work on death during the Civil War, This Republic of Suffering, which has in turn inspired a host of books and articles on the subject, not to mention a quite well-developed literature on how nineteenth-century Americans viewed death overall. But none of it spends very much time on Lincoln.

So, we have this extensive literature on death and the war which hardly addresses Lincoln; and we have this enormous literature on Lincoln which doesn’t address death and mourning. My book tries to bring these two subject areas together.

SG: Was Lincoln’s view of death generally in line with mid-19th Century beliefs and traditions?

BD: Yes and no. Yes in the sense that Lincoln probably did not encounter death much more frequently than most other Americans of his era. I have run across commentary to the effect that Lincoln was steeped in death and suffering because of the deaths of his mother, sister, two children, etc. in an understandable attempt to make him seem like an unusually tragic hero. But in fact Americans in Lincoln’s day routinely encountered the deaths of children and loved ones. Any parent could reasonably expect to lose at least one child, given the prevalence of so much illness and disease back then.

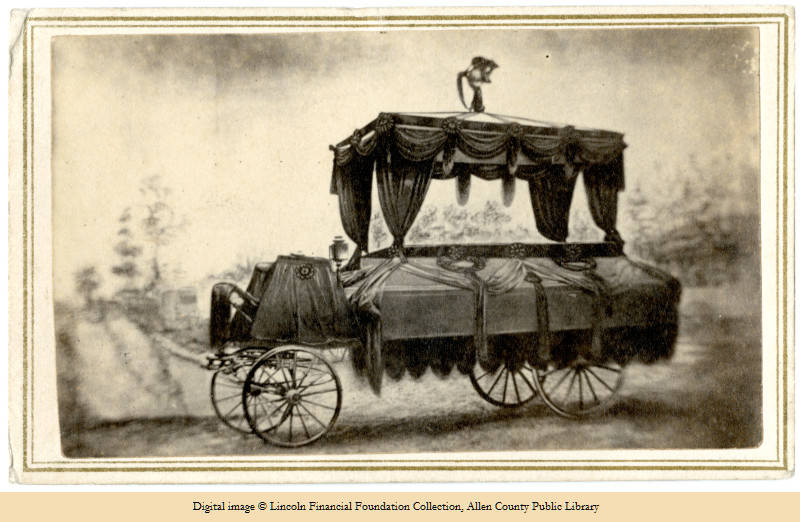

And yes also in the sense that Lincoln by and large followed established customs and rituals for mourning and funerals during his day. Americans followed intricate rules concerning how funerals should be conducted, what the parents of deceased children should wear, etc. Lincoln seems to have, for the most part, observed the same basic mourning rituals of his neighbors

But I’d say no in the sense that Lincoln was not given to an inordinate fascination with questions about death and the afterlife. His was a time during which Americans were often obsessive about questions of whether there was a heaven or a hell, what those might look like, whether people could commune with the spirits of the dead, and so on. Lincoln vaguely believed in an afterlife, but otherwise the subject did not interest him in much detail. Whenever Lincoln’s law partner Billy Herndon tried to engage him in conversations about these things, Lincoln quickly grew bored. So, he was somewhat unique among Americans of his time in that he did not dwell much upon these issues.

SG: We don’t hear as much about son Eddie’s death as we do about Willie. Had Lincoln’s thoughts changed between these two personal tragedies?

BD: You’re right, and I suspect that this is so because Willie’s death is much better documented. Willie died in the White House, surrounded by people who later penned eyewitness accounts of what they saw: Mary’s African American seamstress Elizabeth Keckly, for example, who wrote quite a bit about Willie’s illness and passing, and his parents’ reactions. But we have no comparable sources on Eddy’s death, because when Eddy died in 1850, he did so in a private home in Springfield, when Lincoln was not such a public figure. There are a far fewer reliable primary sources on Eddy’s passing.

As to whether his thoughts changed between the two children’s deaths, it is almost impossible to say. Lincoln was not much given to writing down his thoughts about death and dying as a general thing, and I think that he tended to internalize and suppress his grief. I will say this: the evidence seems to suggest that Lincoln was more emotionally distraught over Willie’s death than Eddy’s, but then this again may simply be a matter of sources, because we have so little information on Eddy’s death and how that was perceived by those around him.

There were also differing circumstances regarding the two children. Eddy’s death, probably from tuberculosis, was a slow, steady decline, lasting for nearly two months; Lincoln had to know what was coming as he watched Eddy deteriorate, and he had time to prepare himself emotionally. Willie, on the other hand, suffered from typhoid, a notoriously unpredictable disease. Willy’s health waxed and waned, to the point that there were times when Lincoln might have reasonably entertained the hope for his recovery; so, his death may have been more of a shock.

SG: In the death of both sons, were Abraham and Mary Lincoln able to console each other, or did they mourn separately.

BD: Great question, and one that’s hard to answer. As a rule, Lincoln was not very comfortable around women who were openly displaying intense emotion. Weeping widows and mothers who during the war tried to elicit his sympathy more often found that such displays unnerved or even agitated him. And particularly in the case of Willie, Mary’s anguish was profound and painful to behold.

I suspect, then, that Lincoln probably kept Mary at some distance, as each underwent a private torment regarding the deaths of their children. I want to stress that this is just an educated guess; much might well have occurred behind closed doors, including Lincoln providing close emotional support for Mary (and vice versa) when they were out of sight from the witnesses who might have later recorded what they saw. But on the whole, Lincoln was inclined, as I said earlier, to internalize his own grieving.

And there is circumstantial evidence suggesting that Abraham and Mary grieved separately. When Mary’s sister visited soon after Willie’s death, Abraham asked her to stay a while to help nurse Mary through her grief. And there is the well-known incident, described by Keckly, in which Lincoln threatened Mary with commitment to a mental institution if she could not control her grief at Willie’s death. These suggest a man putting his wife’s grieving at some arm’s length.

SG: Please comment on the effect that the death of Elmer Ellsworth had on the president.

BD: It really shocked him, for two reasons. First, Lincoln was genuinely fond of Ellsworth, who was a charismatic young man, and a law student who studied for the bar in Lincoln’s law office before the war. Not only did Lincoln like him personally, but Ellsworth was also a favorite of his boys, and Mary. So, losing Ellsworth was much like losing a member of the family.

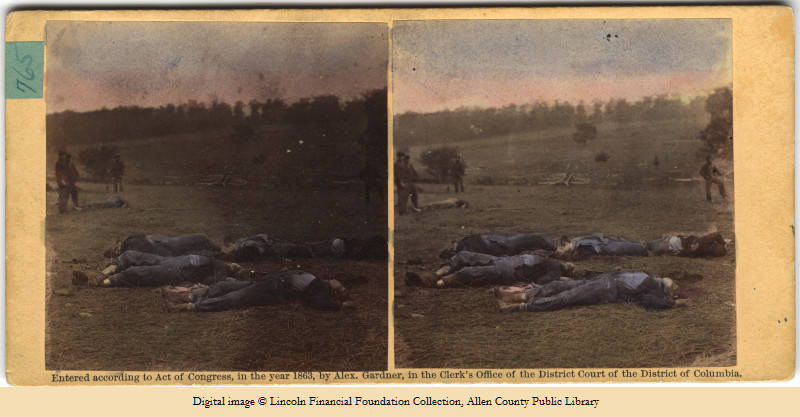

Second, it shocked Lincoln for the same reasons it shocked the nation. When Ellsworth died, he put a real and public face on war deaths. We must remember the naiveté that pretty much everyone from Lincoln on down harbored about war in May 1861. Hardly anyone had died in the Civil War at that point; people didn’t know that the horrific bloodletting of an Antietam or a Shiloh or hundreds of other battles were just over the horizon. And unlike today, Americans of that time did not have access to realistic books or artwork that might educate people on just how horrible battlefield deaths could be. There was no equivalent of Saving Private Ryan, or All Quiet on the Western Front, or any of the graphic and often disillusioned depictions of combat as a grisly bloodbath we see in our time. Everyone knew that soldiers died in battle, of course; but until Ellsworth died, and in such a bloody and violent fashion—having a hole blown is his chest from a shotgun blast by an angry old man—it hadn’t really been driven home to Lincoln, or anyone else, just how bad this new civil war was going to be. Lots of handsome young men were going to die; Ellsworth was just the first.

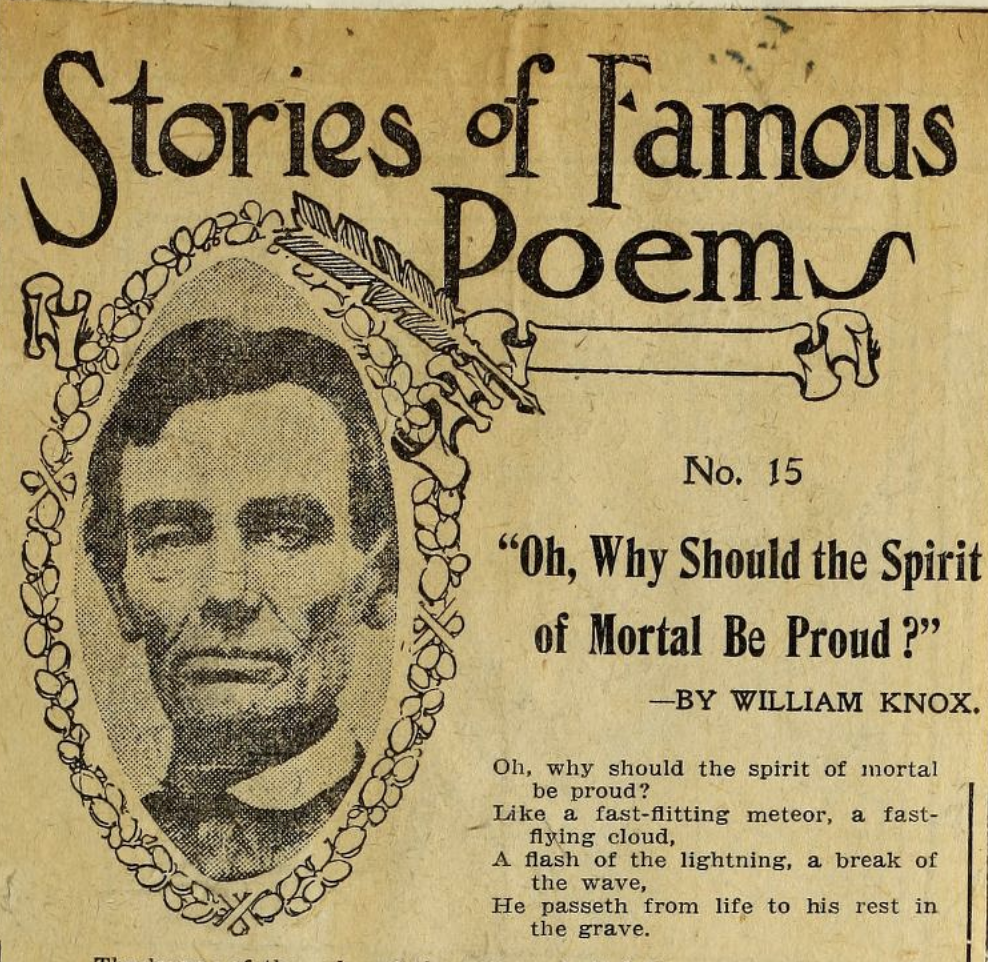

SG: Lincoln’s fascination with the poem Mortality by William Knox certainly suggests melancholy today. Was the poem a fairly typical manifestation of 19th Century thought?

BD: Yes; or at least, one strain of nineteenth century thought, the strain that filtered death and dying through the lens of a morose Calvinistic fatalism. Insofar as Lincoln thought much about death before the war at all, he tended to filter it through his Hardshell Baptist upbringing, with its Calvinist emphasis on the inscrutability of God’s plan. We all die, but no one knows why we die, what purpose it serves, or what comes next; and this sort of acceptance of death’s mystery was integral to Lincoln’s understanding of death. Likewise, Knox’s poetry has that same sense of profound and unknowable tragedy; we die, no one knows why, and we must simply acceptance the sadness and mystery of that fact.

SG: Was President Lincoln’s response to the death toll of the Civil War similar to that of other wartime presidents?

BD: That’s another great question, and I’d have to say that, on the whole, yes. As I argue in my book, Lincoln had to eventually learn during the war to put some emotional distance between himself and the war’s awful human cost; otherwise, he wouldn’t have been able to do his job, or protect his very sanity. The other comparisons with presidents are (to a greater or lesser extent) FDR and Truman during World War II, and LBJ and Nixon during Vietnam. And I think that, in each case, presidents must develop what amounts to an emotionally callous regarding the war’s dead; they must, in order to do their jobs, insulate themselves from thinking over long on war’s miseries. One thinks of Truman’s decision, for example, to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. Whether one agrees with that decision or not, one sees in Truman a willingness to make a rather cold calculus: kill some people, the Japanese civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to save many others.

Lincoln had to develop a similar capacity, and in my book I suggest he did so. Now, this is not at all to say that he became a callous, unfeeling man—quite the contrary. But he seems to have learned to accept the war dead as part of a larger process over which he actually had little control, a process tied to an unknowable Divine plan which he did not truly understand. This admittance that he did not really control the war’s events, and especially the numbers of dead soldiers, in the end gave him a certain amount of acceptance, perhaps even a bit of inner peace.

SG: Please tell our readers of your conclusions regarding Lincoln’s eulogy for Henry Clay.

BD: I saw in Lincoln’s eulogy what I termed the politics of death. When Lincoln delivered that eulogy in 1852 (one of only three eulogies he ever composed), he was beginning to slowly emerge from the semi-retirement from politics he undertook after he returned from Congress; and he was beginning to turn his energies towards the slavery question, something about which he had said relatively little prior to that point.

So, in 1852 he is beginning to find his way back into politics, and antislavery themes; and at that point, Clay dies, and he is asked to write a eulogy. And he turns that eulogy into what amounts to a political document, a re-introduction of himself back onto the public political stage. He offers a long overview of Clay’s career that is also a window into Lincoln’s own ideas about politics, and especially the slavery issue, as Lincoln points out Clay’s antislavery principles and his leading role in the American colonization movement, which Lincoln at the time also supported. In effect, Lincoln uses the eulogy as a sort of political speech.

I call it in the book a “political” use of Clay’s death, but in doing so I don’t mean to imply anything negative or cynical at all about Lincoln. Rather, he was doing what many Americans of his day did when they composed eulogies: combining veneration for the dead with statements regarding the values and principles of the living.

SG: Your bibliography for The Black Heavens is impressive. What research: (1) taught you things that you hadn’t known before; (2) caused you to look at certain aspects of this story in a different light; and (3) confirmed previously held convictions?

BD: This book took me to places in my research I had not entirely expected. There is a vast literature regarding funerals in Lincoln’s time, for example, part of the social and cultural history of that age. I learned a great deal about the intricate rules surrounding mourning customs and dress, processions, coffins, etc.

I think the incident that most surprised me as I dug into the research was the scandal surrounding Lincoln’s visit to Antietam in 1862, something of which I had vaguely heard about but I had not given much attention. He was accused of disrespecting the war dead by having Ward Hill Lamon sing what the press claimed were “ribald Negro songs” while they literally trod on the graves of the dead men. This was untrue, but it was amazing how quickly this story gained traction, how widely it was disseminated, especially in the opposition press, and how worried Lincoln was about it, especially when the story resurfaced during the 1864 elections. Until I wrote this book, I was unaware of just how big this scandal was.

I was also somewhat surprised at how the sources regarding Lincoln’s dabbling with Spiritualism fell apart upon closer examination. I’ve long been familiar with the tradition that Lincoln attended seances, believed in ghosts and the like, and (along I’m sure with many others) sort of half-way believed them, especially given Mary’s well-documented Spiritualist tendencies after the war. I thought there must have been something to this, even if the stories were exaggerated. But once I drilled down to the bottom of the primary sources, I discovered they are of highly dubious quality. I now believe that Lincoln probably never attended a séance (though Mary did so), was not really a Spiritualist in any meaningful sense, and was embarrassed by the rumors that he was one of their own.

While we are on the subject of Mary, I also found that my research tempered my views of her reaction to the deaths around her. Like many others, I had always believed she reacted in a highly unstable and visible fashion to the deaths of her children Eddy and Willie, and that in doing so she was a continual source of embarrassment for her husband. But in fact my research shows she seems to have handled Eddy’s death relatively well, following the established rules of her time for mothers in mourning; and even her highly distraught reaction to Willie’s death was largely a secret from the public. Yes, she was having serious emotional problems regarding Willie, and there is hard evidence she involved herself in some Spiritualist rituals, trying to contact Willie in the afterlife, but she did these things actually rather quietly.

The bottom line is that the book was quite an education for me as I wrote it.

Brian Dirck is Professor of History at Anderson University in Indiana.