In Defense of History

In Defense of History

In Defense of History

Sara Gabbard

Daniel Boorstin, Pulitzer Prize winning historian and Librarian of Congress, once said that “trying to plan for the future without a sense of the past is like trying to plant cut flowers.”

A statement from John Adams expresses the passage of time and the resulting changes:

“I must study politics and war that my sons have the liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.”

Abraham Lincoln also had something to say about the subject. In his December 1, 1862, Message to Congress he stated:

“Fellow-citizens we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.”

Should we be offended that Parson Weems made up the entire story of the young George Washington confessing that he had, indeed, chopped down the cherry tree? At the very least, should we point out that the story was meant to promote manly virtues and that the use of Washington’s name would give the effort a stronger effect…or is it altogether wrong to create such historical fiction? And what of Thomas Jefferson? Before the advent of DNA analysis, charges of his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings could be written off as the ravings of political opponents.

Should scientific evidence taken from DNA samples from current Jefferson and Hemings family members change the way in which we view Jefferson’s political career? Does the language of the Declaration of Independence become less eloquent? If we put him in the context of his time, (he was, after all, a widower and sexual relationships between master and slave were commonplace), or…are some things simply wrong…period. Are we dabbling in situational ethics if we excuse such behavior?

Historian William Manchester has coined a great term for this tendency to judge past eras by the standards of the present: “generational chauvinism.” Do we really have every right, and indeed the responsibility, to judge figures and events from history in terms of our own ethics and values?

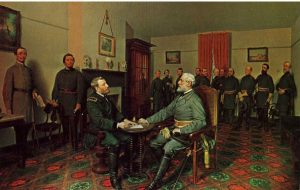

In 2015 we marked the 150th anniversary of the final battles of the Civil War, the treaty at Appomattox, the ratification of the 13th Amendment, and the assassination of our 16th President. What did it all mean? Did the Treaty of Appomattox really end the Civil War…or can we still find remnants of this devastating national experience today?

The passage of the 13th Amendment ending slavery was necessary, given the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation was intended as a war measure only. Abraham Lincoln claimed authority to issue the Proclamation because the Constitution’s Article Two, Section Two designated that the President was Commander in Chief of the armed forces. At the end of the Proclamation, he is careful to add legal justification: “And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.” He covers all of the bases: Constitutional authority and military necessity. And then as frosting on the cake, he invokes the judgment of both mankind and God.

Does anyone really think that the 13th Amendment changed ideas about race once and for all times? Pulitzer Prize winning Historian Eric Foner uses the term “creative forgetfulness” to describe the manner in which the American public frequently ignores the subject of chattel slavery in our past. The great African American thinker W.E.B. DuBois said that “the slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

And what of the Civil War itself? I can’t begin to count the number of times I have seen the question posed: Did the North win the War…or Did the South lose it….as if somehow the thought that the outcome was a bit of both shouldn’t be considered. The Northern victory at the very least resolved two fundamental questions: Was the Union indivisible and was slavery to remain as an institution which seemed to denigrate the precepts upon which the nation was founded?

There are discordant historical views of Robert E. Lee. Throughout the years since the Civil War, Northerners and Southerners alike have honored him as a courageous and noble military leader. But I have a couple of questions:

When push came to shove, he declared himself to be a Virginian first. Is that how we should think of ourselves…as a citizen of our state first and an American second? How could he turn his back on the nation which he had served so honorably? How could he think of his state before his country? Some historians even equate Lee’s love for Virginia with the eventual defeat of the Confederacy because he concentrated so much of his attention and resources on the Army of Northern Virginia…without really paying much needed attention to, for instance, the war in the West.

Pulitzer Prize winning historian James McPherson gives an intriguing look at judging Lee when he says:

“Without Lee the Confederacy might have died in 1862. But slavery would have survived: the South would have suffered only limited death and destruction. Lee’s victories prolonged the war until it destroyed slavery, the plantation economy, the wealth and infrastructure of the region, and virtually everything else the Confederacy stood for. That was the profound irony of Lee’s military genius.”

As he signed the peace treaty at Appomattox, Lee said:

“After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” In commenting on Lee’s statement, historian Richard Current said a century later…”In view of the disparity of resources, it would have taken a miracle to enable the South to win. As usual, God was on the side of the heaviest battalions.”

Some believe that, after the telling defeats at Vicksburg and Gettysburg during the first week of July 1863, Lee should have recognized that the war was lost. Therefore, all loss of life, family disruption, destruction of property for the last year and a half of the war can be laid directly upon his shoulders. He could have surrendered at any time. Alan Nolan believes that:

“Lee fought on in the absence of any rational purpose except to salvage the South’s honor…as well as his own personal honor. There is, of course, a nobility and poignancy, a romance, in the tragic and relentless pursuit of a hopeless cause. But in practical terms, it meant another two or three hundred thousand dead.”

Some historians have blamed the Southern defeat on what they called “the Celtic heritage” of Southerners. They contend that this Celtic outlook maintained that they would follow not only the concept of offensive warfare, frequently ignoring the concept of defensive strategy…but that they would also cling to the notion of heroic, desperate charges against overwhelming odds. If you have ever visited Gettysburg and viewed the terrain in which Pickett’s charge took place, you would understand this statement. There is a wide meadow over which Pickett and his men charged against superior Union forces which had not only an elevated position but one that was also protected by trees and boulders. Like the Celtic warriors of the past, they simply charged the enemy’s well-fortified position.

Eventually, Lee would accept the blame for ordering the charge that was doomed to defeat, but I have always been fascinated by the fact that after the war people tried to get George Pickett to place blame for his debacle on Confederate military decisions. When he was asked who was responsible for the defeat at Gettysburg, he replied: I’ve always thought that the Yankees had something to do with it.”

There is a book titled Fighting over the Founders: How We Remember the Revolution (by Andrew Schocket) which is written with the same thought in mind. There is a concept called “Founders’ Chic,” and the author seeks to differentiate between our almost mythological view of the Founding Fathers and a more realistic depiction of their lives.

As with so many other topics of interest, Winston Churchill weighed in on the concept of history’s treatment of individuals: “History will be kind to me for I intend to write it.” He also said: “If King Arthur did not live, he should have.”

And my favorite comment on the subject comes from an African proverb: “Until lions learn to write, the history of the hunt will be told by the hunters. “

Some Northern citizens were unmoved by discussions of slavery, possibly because they really didn’t feel connected to the issue. Abolitionist sentiments were certainly strong in the North, but we must be careful to draw a line between Radical Abolitionists and those who were anti slavery. Radical abolitionists had no qualms about using whatever means were necessary to end slavery. Perhaps the best example of this outlook can be seen by studying the career of John Brown…from his murder of pro slavery settlers at Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas, to his attempt to storm the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in order to steal weapons which could then be distributed to slaves so that white owners and their families could be massacred.

Anti slavery advocates believed that the institution was wrong…but that the means to end it were complicated and should be conducted within the proper legal framework. I believe that Abraham Lincoln was firmly antislavery…but he was not a Radical Abolitionist. Perhaps his most eloquent comment on the subject was a short, concise sentence: “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” Some have called slavery the great paradox of American history…a land of freedom, supported socially and economically by what was called a “peculiar institution,” an institution which had been a part of civilization since the dim mists of time. But it has always been difficult to back away from such practices. Although we might not like to admit it, the statement that “We’ve always done it that way” is a powerful argument in favor of the status quo. And a nostalgic look back over 160 years brings to mind the inevitable question: Was the Civil War a just or moral war? In fact, can there be a just or moral war?

Thomas Aquinas mentions 3 requirements for a just war:

1. “The authority of the sovereign by whose command the war is to be waged.” If one believes that the formation of the Confederacy was illegal in the first place, then the South cannot claim to have been fighting a just war because their government was invalid and was, therefore, incapable of declaring war. If formation was justified, then the point can be made that this new, legitimate nation had every right to declare war.

2. “A just cause is required, namely that those who are attacked should be attacked because they deserve it on account of some fault.” I find this statement from Aquinas to be a bit dicey because who gets to determine fault and assign blame.

3. “It is necessary that the belligerents should have a rightful intention, so that they intend the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil.” Here again, what person or institution gets to define rightful intention?

Philosophers and historians have added other stipulations since the time of Aquinas: The concept of a just cause has been given some qualifying explanations: Protecting people from aggression (a defensive war); Restoring rights that have wrongfully been taken away; and Reestablishment of a just political order.

Many would say that war should only be used as a last resort and that response should be what scholars term proportional in nature. Sherman’s March to the Sea with his “scorched earth” policy is most frequently cited as an example of non proportionality during the Civil War. However, it could be cited as indicative of his belief that it was necessary to both destroy the enemy’s resources and to break his will. And after all…THEY started it by firing on Fort Sumter…not to mention the understandable response to enemies after seeing one’s comrades killed or horribly wounded in past battles.

And here’s a definition of just war that seems improbable…if not impossible…There should be “right intention” in a war with “no drumbeat of hatred, demonization of the enemy, or desire for revenge.” How should we today study and reflect upon the Civil War? Does our outlook depend upon where we live? On our race? On our views of the proper role of the federal government?

And what of our view of Abraham Lincoln? In Lincoln in American Memory, Merrill Peterson lists five themes in what he calls the apotheosis of Lincoln: Saviour of the Union; Great Emancipator; Man of the People, the First American; and the Self-Made Man.

Savior of the Union and Great Emancipator encompass his Presidential and Commander-in-Chief roles and are most easily supported by a study of history. However, many believe that the title of Great Emancipator is misleading because it fails to take into account the role of those enslaved in freeing themselves. Perhaps it is incorrect to consider this to be an either/or question. Certainly, the participation of the president was vital. But one can also state that some of the great Black leaders such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth made an enormous impact…as did the 200,000 African Americans who served in the Union military during the Civil War.

Again quoting James McPherson:

“Without the Civil War there would have been no confiscation act, no Emancipation Proclamation, no Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, no self-emancipation, and almost certainly no end of slavery for several decades at least. The common denominator in all of the steps that opened the door to freedom was the active agency of Abraham Lincoln.”

And when given the opportunity to drop back from emancipation when it looked as if he might not be re-elected in 1864, Lincoln said:

“I should be damned in time and in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends and enemies, come what will.”

Man of the people and self-made man are a bit more difficult to pin down because over 160 years Abraham Lincoln has assumed an almost mystical/mythical status in American history. A perfect example is the opening sentence of a college student’s essay: Lincoln was born in a log cabin that he built with his own hands.

J. David Greenstone believes that Lincoln’s great achievement was to fuse Liberty and Union. Greenstone states that there are two distinct forms of freedom: freedom FROM and freedom TO. Some laws give us protection FROM both governmental agencies and other citizens. Other laws give us the freedom TO pursue certain dreams and activities.

We can certainly raise questions about Lincoln’s legacy:

Did his willingness to suspend habeas corpus result in a dangerous precedent?

Did his interpretation of presidential authority as commander-in-chief also provide a convenient justification for future presidents to expand their power?

Or…are these two questions irrelevant and impossible to judge from this safe distance away from a besieged national government?

Would he have been better able to handle the thorny problems presented by Reconstruction…or, like Andrew Johnson, would he have been unable to cope with the awful aftermath of such a devastating war? Would he have found the grand words of his Second Inaugural…with malice toward none, with charity for all an impossible goal, or would his stature, eloquence, and strength of character have enabled him to convince all sides that these precepts were not only possible but also fundamentally necessary?

Does he truly deserve the almost mythological reputation that has been created over 160 years? My best answer to this question is to quote William Lee Miller in his magnificent book Lincoln’s Virtues: An Ethical Biography:

“It is a curious truth – is it not? – that an unschooled nineteenth century American politician named Abraham Lincoln, from the raw frontier villages of Illinois and Indiana, has turned out to be among the most revered of the human beings who have ever walked this earth. Curious – and perhaps a little moving, if you think about it. Except for religious figures, he has had few superiors on the short list of the most admired, and the even shorter list of the most loved, of humankind. Among his countrymen, I believe, he had – given the vicissitudes of Jefferson’s reputation and a certain loss of popular attachment to George Washington – no equal. There he stands: tall, homely, ready to make a self-deprecating joke, stretching higher than the greatest of his countrymen, an unlikely figure among the mighty of the earth.”

Sara Gabbard is executive director of Friends of the Lincoln Collection of Indiana and editor of Lincoln Lore.