God and Mr. Lincoln

On the day in April 1837 that Abraham Lincoln rode into Springfield, Illinois, to set himself up professionally as a lawyer, the American republic was awash in religion. Lincoln, however, was neither swimming nor even bobbing in its current. “This thing of living in Springfield is rather a dull business after all, at least it is so to me,” the uprooted state legislator and commercially bankrupt Lincoln wrote to Mary Owens on May 7th. “I am quite as lonesome here as [I] ever was anywhere in my life,” and in particular, “I’ve never been to church yet, nor probably shall not be soon.” Lincoln blamed this on his own shyness and lack of social grace:”“I stay away because I am conscious I should not know how to behave myself.”1

But awkwardness was not actually Lincoln’s principal reason for avoiding Springfield’s religious life; it was because he did not have much religious life of his own to speak of. His stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, would tell Lincoln’s biographer and law partner William Henry Herndon that “Abe had no particular religion” as a youth, and “didn’t think of that question at that time, if he ever did,” or at least “never talked about it.” It was not from ignorance. The young Lincoln “would hear sermons preached, come home, take the children out, get on a stump or log, and almost repeat it word for word,” and do it so convincingly that he could make “the other children as well as the men quit their work” to listen to him. But it was all pure mimicry. Once Lincoln struck out on his own, he not only showed no interest in religion, but an actual aversion to it. During his brief years as clerk and storekeeper in New Salem, Illinois, Lincoln preferred the reading of the most famous anti-religious skeptics of the day—”Voltaire, Paine &c”— and wrote a short essay which was so scandalous in its contempt for religion that his neighbors “morally compelled Mr Lincoln to burn the book, on account of its infamy.”

Moving to Springfield did little to change Lincoln’s attitude. “I Knew Mr Lincoln as Early as 1834-37,” recalled James Matheny, the best man at Lincoln’s wedding and the clerk of the Sangamon county court, and “Know he was an infidel.”

He…used to talk Infidelity in the Clerks office in this city about the years 1837-40. Lincoln attacked the Bible & new Testament on two grounds1st From the inherent or apparent contradiction under its lids & 2dly From the grounds of Reason sometimes he ridiculed the Bible & New Testament sometimes seemed to Scoff it, though I shall not use that word in its full & literal sense never heard that Lincoln changed his views though his personal & political friend from 1834 to 1860Sometimes Lincoln bordered on absolute Atheism: he went far that way & often shocked me.2

What should have been shocking, however, was not Lincoln’s lack of religion, but the fact that Matheny should have found it shocking; or, to put it another way, the real surprise in Lincoln’s lack of religious profile was that the rest of the American republic had such an unusually large one.

Religion—and for all practical purposes, this meant Protestant Christianity— permeated the life of early America, first because so many of the refugee colonies planted in British north America were the planned communities of fervent and persecuted religious sects in England—Puritan independents, Quakers, Catholics—and second because even those settlements which weren’t the direct offspring of sectarian zeal (New York, Virginia) still transferred the state sponsorship of the legally established Church of England to their shores. “In eighteenth-century America – in city, village, and countryside – the idiom of religion penetrated all discourse, underlay all thought, marked all observances, gave meaning to every public and private crisis,” wrote Patricia Bonomi. When the 18th-century evangelical revivals reached America in the 1740s as the “Great Awakening,” they had the impact (said Richard Bushman) of “the civil rights demonstrations, the campus disturbances, and the urban riots of the 1960s combined.”3

But then, of course, came the Revolution, which overthrew more than merely crown rule in America. The Church of England was nearly erased, as close to half of its clergy fled into exile.4 But the other major religious alliances whose churches had dominated the pre-revolutionary landscape—Presbyterians, Baptists, Lutherans—also suffered, even though many of them had volunteered to support the Revolutionary cause. “Perhaps no set of men, whose hearts were so thoroughly engaged in it, or who contributed in so great a degree to its success,” wrote Peter Thacher, a Massachusetts parson, in 1783, “have suffered more by it.” The Revolution not only disrupted the day-to-day habits of colonial society; it transformed governance into a new republican order based on hostility to authority and hierarchy.5 After the smoke of the Revolution had cleared, the Revolution’s first native-born historian, David Ramsay, was convinced that “This revolution has introduced so much anarchy that it will take half a century to eradicate the licentiousness of the people.”6

It did not help, either, that the Revolutionary leadership was itself notably indifferent to religion. The men who founded the political order of the new republic had taken pages from the central political texts of the Enlightenment, and many of them, not stopping at politics, had absorbed the Enlightenment’s distaste for religion as an explanation of the universe. “Boys that dressed flax in the barn,” recalled Lyman Beecher, “read Tom Paine [the author of The Age of Reason] and believed him”; his fellow-students at Yale “were infidels, and called each other Voltaire, Rousseau, D’Alembert, etc., etc.”7 Liberty, John Adams wrote in his NovAnglus essays in 1775, “can no more exist without virtue and independence than the body can live and move without a soul.” But Adams’s own religion was a colorless Unitarianism which reduced the Christian Trinity to a single personality, and an exceedingly remote one at that.8 Thomas Jefferson frankly considered himself “an Epicurean,” which he defined as a belief that “the Universe” was “eternal” and composed of “Matter and Void alone.” He did not doubt that there was a Creator of sorts and appealed in the Declaration of Independence to “Nature’s God.” But Nature’s God was not the Christian one. As late as 1822, he was serenely predicting that “there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die an Unitarian.”9

Jefferson was, of course, wrong. Between the year Jefferson left the presidency (which was also the year Lincoln was born) and the year Lincoln was elected president, the American religious landscape heaved upwards in a volcanic eruption of religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening. The results were even more remarkable than in colonial times. The total number of Christian congregations in the United States swelled from 2500 in 1780 to 52,000 by 1860—nearly three times the growth of the American population. And the more robustly evangelical their Protestantism, the more the churches grew: Baptist congregations soared from 400 in 1780 to 12,150 in 1860; Methodists grew from 50 to 2500. Even the staid Episcopalians were bitten by evangelical revival, sprouting evangelical dioceses, newspapers, magazines, and two theological seminaries. In the four years preceding the Civil War alone, the Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian and Episcopal churches netted increases of over 446,000 members, and Richard Carwardine estimates that 40% of the American population identified itself as evangelical and Protestant, with perhaps another 20% falling within a circle of evangelical “hearers.” By the time he was inaugurated in 1861, Abraham Lincoln was on the verge of becoming an anachronism.10

Lincoln was not unconscious of how out-of-step he was with other Americans or of the political penalty he was liable to pay as a result. As a cocky twenty-something Springfield lawyer, Lincoln continued to draw inspiration from Sir Charles Lyell’s naturalistic Principles of Geology (1830-33) and Robert Chambers’ proto-Darwinian Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). “Lincoln then had a smattering of Geology,” James Matheny recollected, and “was Enthusiastic in his infidelity.” But as the cultural climate changed and “he grew older, he grew more discrete—didn’t talk much before Strangers about his religion.” By the time he was in full mid-career stride in the 1850s, he had become so reluctant to talk about religion that David Davis, the rotund presiding judge of the Eighth Judicial Circuit, could conclude that not only did he not “know anything about Lincoln’s Religion,” he could confidently state that he didn’t “think anybody Knew. The idea that Lincoln talked to a stranger about his religion or religious views or made such speeches, remarks &c about it as published is absurd to me.” 11

Lincoln had good reason for reticence: a man with political ambitions like Lincoln’s was doing himself no favors by talking-down religion. “It was every where contended that no Christian ought to go for me, because I belonged to no church,” Lincoln complained in 1843, and this “levied a tax of a considerable per cent. upon my strength throughout the religious community.” When he ran for Congress in 1846, his opponent was the celebrated Methodist revival preacher, Peter Cartwright, who had no scruples about reminding voters in the 7th Congressional District that a vote for Lincoln was a vote against God. Lincoln was not inclined to change his colors just for an election, but he did not mind obscuring them a little, either. The handbill he circulated to counteract Cartwright’s charges conceded that the charge “That I am not a member of any Christian Church, is true.” But the balance of the handbill shrewdly concentrated on what Lincoln was not—”an open enemy of, and scoffer at, religion”— rather than what he was, which was a closeted scoffer.12

Lincoln also knew better than to make unnecessary trouble for himself within his own household and among his friends. His father, Thomas, and stepmother were lifelong adherents of a strict Baptist sect, the Separate Baptists, and when Lincoln received word that Thomas Lincoln was dying in 1851, he was careful to phrase his farewells in terms that would offer the old man no parting grief. “Tell him to remember to call upon, and confide in, our great, and good, and merciful Maker; who will not turn away from him in any extremity. He notes the fall of a sparrow, and numbers the hairs of our heads; and He will not forget the dying man, who puts his trust in Him.” Personally, Lincoln was not sure of any survival of consciousness beyond death and frankly told a New Salem neighbor that he could not believe in “any future state.” For his father, however, he was gentler and more soothing: “he will soon have a joyous [meeting] with many loved ones gone before.” 13

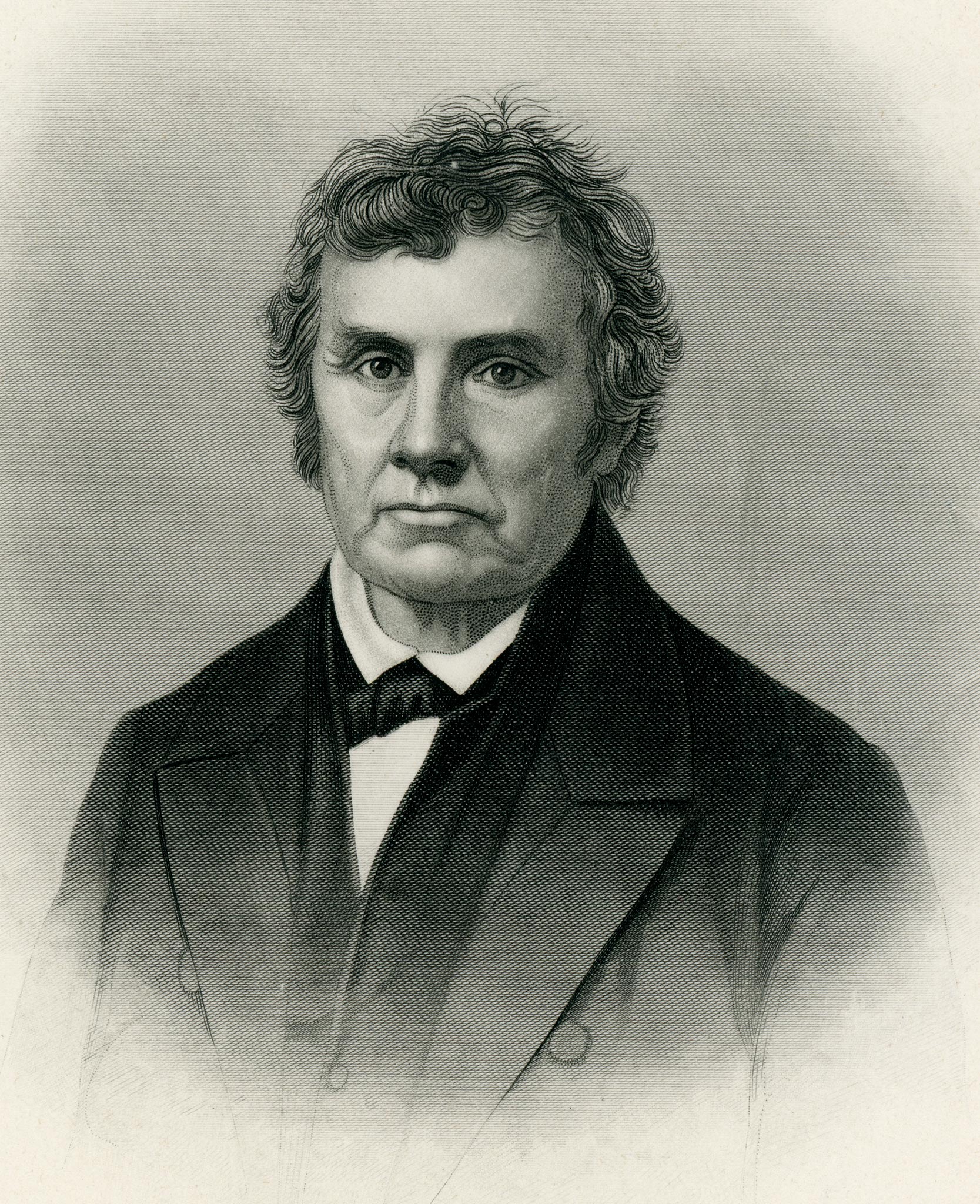

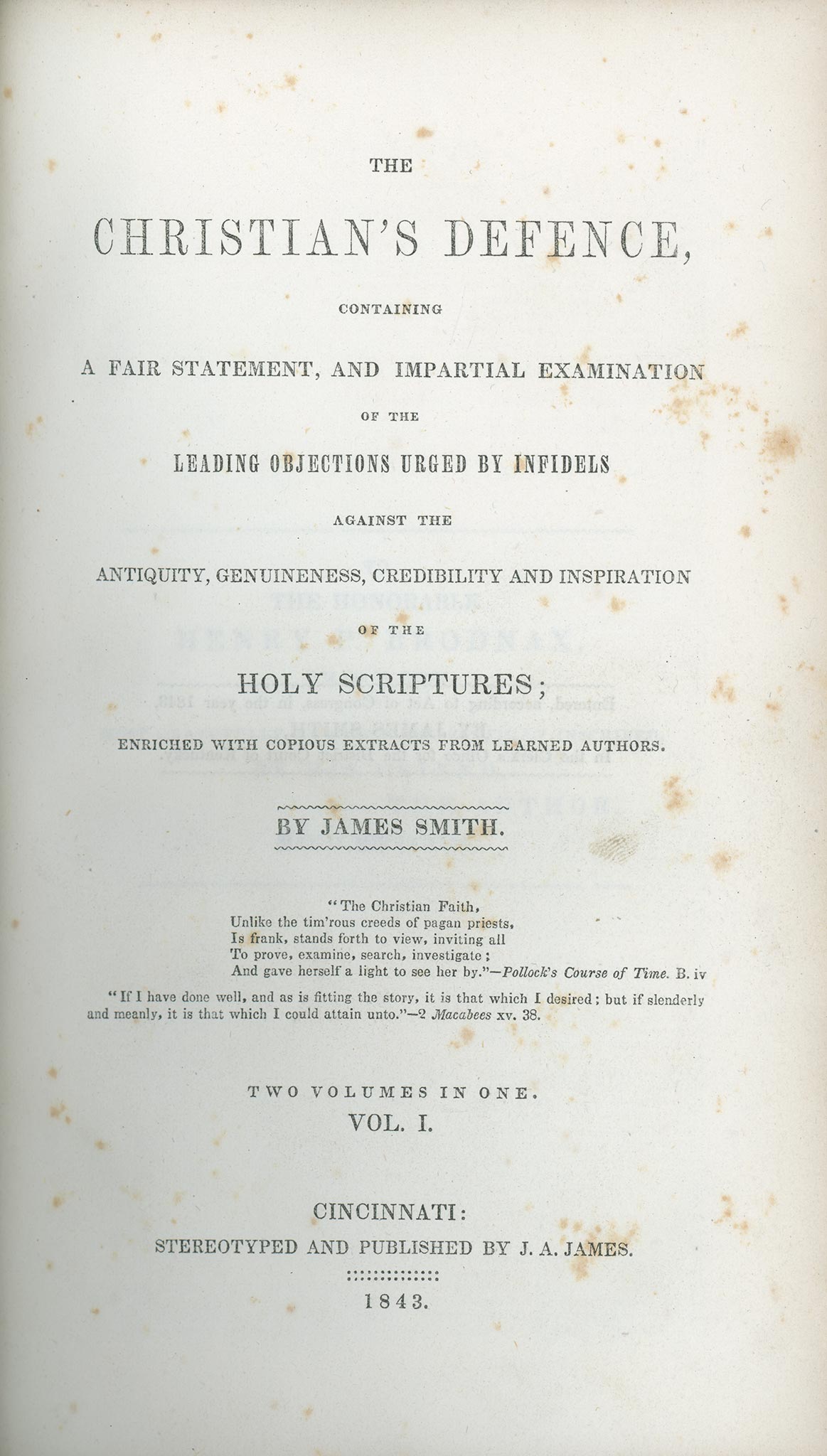

For James Matheny, comments of this sort were evidence that “Lincoln played a sharp game here on the Religious world.” Wanting to “avoid the disgrace—odium and unpopularity” of the “Atheistic charge,” he encouraged the religious-minded to “Come and convert me.” After the death of his second son, Edward Baker Lincoln, in 1850, he held long discussions with the minister of Springfield’s First Presbyterian Church, James Smith (himself an adult convert from “infidelity” of the Tom Paine variety), read Smith’s The Christian’s Defence (1843), and allowed people to conclude that “I am now convinced of the truth of the Christian religion.” But even that statement was ambiguous: being convinced was the result of logic, but it did not guarantee faith if the premises of that logic were in question.15 The “evidence of Christ’s divinity came to us in somewhat doubtful shape,” Lincoln cautioned Springfield postmaster James W. Keyes; what was more obvious to Lincoln was that “the system of Christianity was an ingenious one, at least, and perhaps was calculated to do good.” So, the Christian religion could be more-or-less embraced because of its practical benefits even if its theological certainties were questionable. And for a politician who respected public opinion as the factor which “settles every question here,” Lincoln had to admit that “the universal sense of mankind…in favor of the existence of an over-ruling Providence” was an argument “men ought not, in justice, to be denounced for yielding to…or for giving it up slowly.” One could still profess “a simple faith in God” while remaining uncertain whether “the author of our being” ought to be “called God or Nature,” and for Lincoln, it actually “mattered little which.” 16

Leonard Swett, one of Lincoln’s closest legal associates and himself a Presbyterian elder, was sure Lincoln “believed in God as much as the most approved Church member.” On the other hand, he also recognized that Lincoln defined God on his own terms: “he judged of Providence by the same system of great generalization as of everything else.” It certainly produced no remarkable changes in Lincoln’s behavior. “He had in my judgment very little faith in ceremonials and forms,” Swett wrote, “Whether he went to Church once a month or once a year troubled him but very little.” The minister of Springfield’s Second Presbyterian Church agreed. “He makes no pretensions to piety. During the time I have known him, I never heard of his entering a place where God is worshiped…. He often goes to the railroad shop and spends the sabbath in reading Newspapers, and telling stories to the workmen, but not to the house of God.”17 Nor did Lincoln care to associate himself with reform movements that smacked too strongly of religious zeal. Lincoln’s abhorrence of alcohol only enlisted his sympathy with the secular Washington Temperance Society, which “many Christians” in Springfield “twisted up their noses at,” and his 1842 temperance lecture for the Washingtonians scorned the efforts of “Preachers, Lawyers, and hired agents” who “have no sympathy of feeling or interest, with those persons whom it is their object to convince and persuade.”18

And yet, the overall geography of Lincoln’s mind was not entirely a map of logic, or even skepticism. Orville Hickman Browning thought that “Mr. Lincoln had a tolerably strong vein of superstition in his nature.” Herndon, too, noticed that Lincoln “believed more or less in dreams—consulted Negro oracles—had apparitions and tried to solve them” and “sought the advice of the spirits.” After his oldest son, Robert, was bitten by a dog Lincoln feared was rabid, he took the boy to Indiana to be cured by the application of the Terre Haute “madstone.”19 In June of 1863, he urgently wired Mary Todd Lincoln in Philadelphia to take away his youngest son Tad’s “pistol” because “I had an ugly dream about him” (and this is only part of a larger tapestry of fearful dreams Lincoln had about his own death, all of which became the stuff of legend after his assassination).20 And for a man who was otherwise indifferent to formal Christian theology, Lincoln had some very decided opinions about specific practices. “He thought baptism by immersion was the true meaning of the word; for John baptized the Savior in the River Jordan because there was much water and they went down into it and came up out of it.” He considered the doctrine of the “endless punishment” of the wicked as contradictory, since “punishment was parental in its object, aim, and design, and intended for the good of the offender; hence it must cease when justice is satisfied.” 21

Above all, Lincoln retained the deep impress of the stark Calvinist predestination taught by the Separate Baptists. He naturalized this as fatalism, insisting that “every effect must have its cause…in the endless chain stretching from the finite to the infinite” and that each individual was “simply a simple tool, a cog, a part and parcel” of a Great Mechanism of necessity “that strikes and cuts, grinds and mashes, all things that resist it.” Lincoln frequently invoked his “fatalism” as an explanation for why he deserved no particular credit or blame for the outcomes of events he was guiding. “I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity,” he candidly explained to Albert Hodges and Archibald Dixon in 1864, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” But there was no mistaking the hidden hand of his ancestral Calvinism in such disclaimers. He admitted to Joseph Gillespie that “he could not avoid believing in predestination” since he could “never…reconcile the prescience of the Deity with the uncertainty of events.”22 Like Herman Melville, Lincoln despaired of the existence of a personal God; yet, he was sure that if a personal God existed, it would be the Calvinistic one. In such a case, he explained to Aminda Rogers Rankin, “it is to be my lot to go on in a twilight, feeling and reasoning my way through life, as questioning, doubting Thomas did.”23

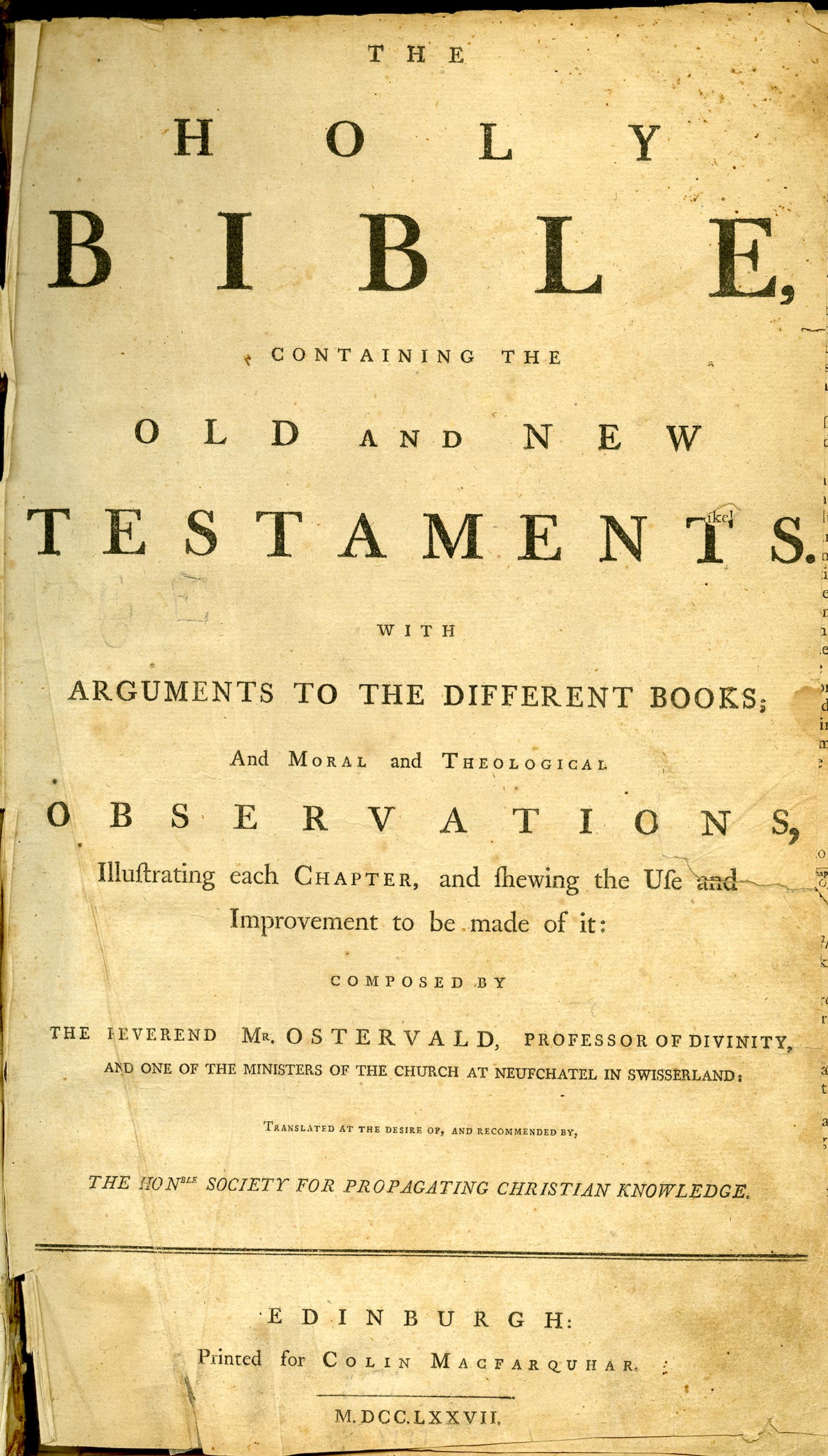

Lincoln might have been no more than one face in the crowd of tormented Victorian unbelievers who found themselves stranded amid the high tide of evangelical Protestant revival, and who (again like Melville) could “neither believe nor be comfortable in his unbelief”—had it not been for the Civil War.24 Lincoln was saved from too much inquiry about religion during his 1858 Senate race against Stephen A. Douglas, or the subsequent presidential race against Douglas in 1860, largely because Douglas himself did not have much of a religious profile to tout. And in the early flush of his presidency, any comments of Lincoln’s which touched on religion were purely boiler-plate. As he left Springfield for Washington, he begged his neighbors to pray for “the assistance of that Divine Being who ever attended” the Founders, since “with that assistance I cannot fail,” and along the route to Washington, he made brief allusions to “the sustenance of Divine Providence” and “trust in that Supreme Being who has never forsaken this favored land,” but without attaching any more specific content. His inaugural address was devoid of religious allusions, apart from a Shakespearean appeal to “the better angels of our nature.”25 In the Executive Mansion, Orville Hickman Browning recalled Lincoln spending Sundays “reading the bible a good deal.” But, Browning told Isaac Arnold, he “never knew of his engaging in any other act of devotion. He did not invoke a blessing at table, nor did he have family prayers.” Even the Lincoln children’s babysitter in the White House, Julia Taft Bayne, remarked that Lincoln “read the Bible,” but did it “quite as much for its literary style as he did for its religious or spiritual content. He read it in the relaxed, almost lazy attitude of a man enjoying a good book.”26

But the ensuing war did not go well, and no one could miss how deeply Lincoln internalized the losses it inflicted. No one, he would later say, “expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained.” North and South alike “looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.” He was deeply puzzled by what seemed to be the ease with which the Southern Confederacy resisted his efforts to subdue it, and the futility of Northern efforts to win the war without over-reaching into the slavery problem. He “believed in the progress of man and of nations,” but Confederate victories seemed to be nothing but the antithesis of progress.27 “If I had been allowed my way, this war would have ended before this,” he wrote in reply to Eliza Gurney; “if it had been left to us to determine it, we would have had no war,” he admitted to Byron Sunderland, the pastor of Washington’s First Presbyterian Church (and the chaplain of the Senate). Instead, the war had not only dragged onwards, generating one horrendous casualty list after another, but had corkscrewed in ways that looked like anything but a Great Mechanism. By the “summer or fall of 1861,” Lincoln was asking question that startled Browning: “Suppose God is against us in our view on the subject of slavery in this country, and our method of dealing with it?” It was, Browning admitted, “the first time” he had ever had an inkling that Lincoln “was thinking deeply of what a higher power than man sought to bring about.” 28

Characteristically, the lawyer who attempted to teach himself logic through reading John Playfair’s edition of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry now attempted to plot his puzzlement as though it were a geometrical proof, starting with a practical axiom: The will of God prevails. This did not necessarily dictate who or what God was, but it did acknowledge that whatever God’s shape, the will of that deity must prevail, since that was in the nature of divine wills. The problem was discerning the direction of that will. “In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God.” This was certainly true of the Civil War, and certainly true of an America whose culture was brimming with theological energy. But now came the statements: “Both may be, and one must be wrong,” the reason for this arising from the law of the excluded middle, that “God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time.” There is, of course, a third alternative: “In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party,” and the reason for this statement is the sheer protractedness of the conflict. “By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.” Ergo: the will of God must point to a goal which cannot be reached until the original goals of both sides – which each imagined, wrongly, to be God’s will – were exhausted and the real purpose of the conflict made manifest. “I am almost ready to say that this is probably true,” Lincoln conceded, “that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet” – or at least not until God’s more sublime purpose became apparent.29

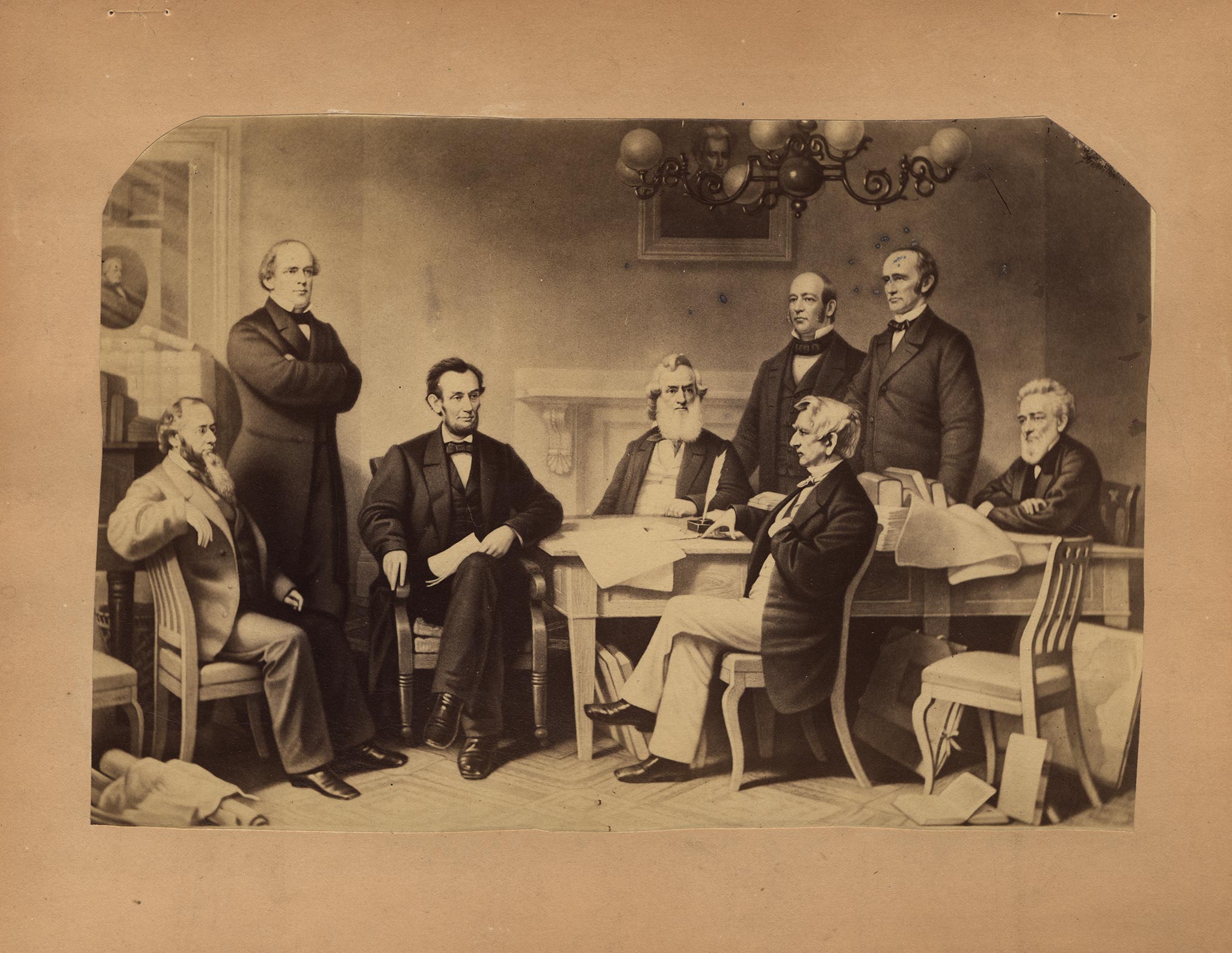

But if this was “probably true,” then its truth demanded a more personal, more lively, more directing, more purposeful and more unpredictable God – a God who ends wars at a word or gives victories in a day – than the mechanical Providence Lincoln had heretofore invoked. Just how personal and unpredictable, showed up in the explanation Lincoln offered for the action he finally decided was the “something different from the purpose of either party,” the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln drafted a presidential emancipation proclamation as early as June 1862, but did not discuss it in cabinet until July 22nd or issue it until September 22nd, five days after the battle of Antietam, based on the argument made by Secretary of State William Seward that such a proclamation needed to come in the wake of a Union victory if it was not to look like a counsel of desperation. Lincoln agreed to wait, as a matter of political calculation; but his reasoning for the proclamation’s eventual release two months later was like no other decision he had ever reached.

When Robert E. Lee and the rebel Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland in the first week of September 1862 (he explained to his assembled cabinet secretaries on September 22nd), Lincoln “determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, to issue a Proclamation of Emancipation.” But he had done so, not as a political calculation, but on the strength of a “promise” he had made to “myself, and – (hesitating a little) – to my Maker. The rebel army is now driven out, and I am going to fulfill that promise.” As Navy secretary Gideon Welles recorded in his diary, Lincoln explained that he “had made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of the Divine will, and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation.” 30

The astonishment which prevailed in that meeting at “the peculiar faith or trait here exhibited” was almost palpable. Lincoln acknowledged that rationales of this sort, especially in matters of high state policy, “might be thought strange,” an understatement so colossal that Treasury secretary Salmon Chase – beyond doubt the most committed evangelical Christian in the cabinet – “asked the President if he correctly understood him.” To the long-time political operatives who populated his Cabinet, it was hard to know what was more unprecedented: that a president would make monumental policy decisions on the basis of personal communications with the Almighty or that Lincoln would be the president to confess such communications. Either way, Lincoln simply repeated that “I made a solemn vow before God, that if General Lee was driven back from Pennsylvania, I would crown the result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves.” So there it was: “God had decided this question in favor of the slaves. He was satisfied it was right” and “was confirmed and strengthened in his action by the vow and the results.”31

William Herndon, who knew Lincoln nearly as well as anyone could, always insisted that Lincoln’s allusions to God were invariably presented with an eye for how they would please the American masses. Even in the presidency, Herndon suspected, Lincoln’s references to God were all for effect. “If he could get the Christians to pray for him,” Herndon complained, “he could chain them to himself and throw them against disunion; he used the Christians, as it were, as tools.”32 But Herndon had some notorious axes of his own to grind on the subject of religion, and his intimacy with Lincoln did not extend to the presidential years. During those years, Lincoln’s invocations of a personal, directing God multiplied, and John Todd Stuart was convinced that Lincoln “had no possible motive for saying what he did” about religion “unless it came from a deep and settled conviction.” Lincoln told Noah Brooks (who had no particular incentive for misconstruing him) that “after he went to the White House he kept up the habit of daily prayer.” It was not extensive, confessional, demanding, or emotional. “Sometimes it was only ten words, but those ten words he had.” The kinds of responsibilities which the presidency, especially in time of civil war, put on him persuaded Lincoln that he could not “hope to get along without the wisdom which comes from God and not from men.” And he told Brooks at one point that among “the many philosophical books” he admired, he “particular liked [Joseph] Butler’s Analogy of Religion…and he always hoped to get at [Princeton’s] President [Jonathan] Edwards on the Will” – anything but casual religious reading.33

Nor were these comments mere political throw-aways, distributed for political effect: in the case of the Second Inaugural, it was actually quite the opposite. His Second Inaugural is one of those rare documents in presidential history – a speech worth reading and parsing – for it constituted something close to a meditation on the nature of justice, and how God’s justice is a very different measure of things than human justice. “American Slavery,” he said, is an offence for which all Americans – North and South alike – must plead guilty, and for which the war scourges North and South alike. No one side has a monopoly on right or on wrong. It might not please many Northerners to hear that they were complicit in slavery, and that God has given “to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came.”

But, Lincoln replied, those who rankled at this conclusion needed to argue with God, not him. In such a punishment as the Civil War had become, “shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?” The titanic, looming sense of God’s sovereignty and the pitifulness of human attempts to escape that sovereignty left only one appropriate response, to show malice toward none, charity for all, and do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations. Far from this tickling the political ears of the Northern electorate, Lincoln knew that they would not be “flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them.” But to “deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world.” Not just creating, or presiding at a distance, but governing.34

Still, it is important to heed Herndon’s caution in at least one respect: Lincoln’s God never seemed to have become the Protestant Christian God. Jesus remained, for the most part, invisible, and Lincoln’s only allusions to “the Saviour” as president came as part of two otherwise routine responses to the delegates of the American Baptist Home Mission Society and to the presentation of a Bible by the “Loyal Colored People of Baltimore.” The letters and memoirs of Lincoln’s White House staff are nearly blank of any religious utterances by Lincoln, apart from a brief “great good luck and God’s blessing go with you” to John Hay in 1864. John Nicolay assured Herndon in May 1865 that “Mr. Lincoln did not, to my knowledge, in any way change his religious ideas, opinions or beliefs from the time he left Springfield to the day of his death.” Not that Nicolay could say what those “ideas” were, “never having heard him explain them in detail; but I am very sure he gave no outward indication of his mind having undergone any change in that regard while here.” 35

Despite the well-meaning efforts of over-eager witnesses to claim after Lincoln’s death that he had made special confessions of faith, or planned to be baptized, or to join a church, there is no evidence at all of any such intentions. “I have often wished that I was a more devout man than I am,” he told a delegation of Baltimore Presbyterians, but this was not a very persuasive marker of deep religious convictions. It was enough for Lincoln to add, “Nevertheless, amid the greatest difficulties of my Administration, when I could not see any other resort, I would place my whole reliance in God, knowing that all would go well, and that He would decide for the right.” 36

It is as unwise to dispute the sincerity of Lincoln’s response as it is to make too much of it. He was, in the end, a child of the Enlightenment, and the Enlightenment’s limited allowance for religion described the boundaries he accepted for it, personally and otherwise. But he was also too curious a mind to allow those boundaries to remain fixed forever, and too attuned to the shifts in American culture to remain utterly indifferent to them. As in so many other respects, he remains a mystery in American religion, but a tantalizing one – like Melville, neither a true believer, nor content in his unbelief.

Allen Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College and the William L. Garwood Visiting Professor for the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University (2017-18).

Endnotes

- “To Mary S. Owens” (May 7, 1837), in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (hereinafter CW), ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ, 1953), 1:78.

- Herndon interview with Sarah Lincoln (September 8, 1865), John Hill to Herndon (June 27, 1865), Hardin Bale to Herndon (May 29, 1865), and Herndon interview with James Matheny (March 2, 1870), in Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, eds. Rodney O. Davis & Douglas L. Wilson (Urbana, 1997), 13, 62, 106-07, 576.

- Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (New York, 1986), 3-6; Richard Bushman, ed., The Great Awakening: Documents on the Revival of Religion, 1740-1745 (New York, 1970), xi.

- Frederick V. Mills, Bishops by Ballot: An Eighteenth Century Ecclesiastical Revolution (New York, 1978), 158; William Meade, Old Churches, Ministers and Families of Virginia (Philadelphia, 1900), 1:29-30

- Mark David Hall, Roger Sherman and the Creation of the American Republic (New York, 2013), 62; Peter Thatcher, Observations Upon the Present State of the Clergy of New-England: With Strictures Upon the Power of Dismissing Them, Usurped by Some Churches (Boston, 1783), 4.

- Ramsay, in Lester H. Cohen, “Foreword” to The History of the American Revolution, (Indianapolis,1990), 1:10

- Charles Beecher, Autobiography, Correspondence, Etc., of Lyman Beecher (New York, 1864), 1:43.

- Richard Vetterli and Gary C. Bryner, In Search of the Republic: Public Virtue and the Roots of American Government (Lanham, MD, 1996), 77.

- “To Samuel Kercheval” (January 19, 1810), “To William Short, with a Syllabus” (October 31, 1819), “To John Adams” (August 15, 1820), and “To Thomas Cooper” (November 2, 1822) in Thomas Jefferson: Writings, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York, 1984), 1213-14, 1430, 1433, 1443, 1464; Jefferson to Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse (June 26, 1822), in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. H.A. Washington (1854; Cambridge University press, 2011), 7:252-3.

- Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, MA, 1990), 270; Kathryn Long, The Revival of 1857-58: Interpreting an American Religious Awakening (New York, 1998), 150; Carwardine, Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (New Haven, 1993), 3-18.

- Herndon interview with David Davis (September 20, 1866) and James Matheny (March 2, 1870), in Herndon’s Informants, 348, 576.

- “To Martin S. Morris” (March 26, 1843) and “Handbill Replying to Charges of Infidelity” (July 31, 1846), in CW, 1:320, 382.

- Parthena Hill, interview with Walter B. Stevens, in Stevens, A Reporter’s Lincoln, ed. Michael Burlingame (Lincoln, NE, 1998), 12; “To John D. Johnston” (January 12, 1851), in CW 2:97.

- Herndon to Ward Hill Lamon (March 6, 1870), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, ed. Douglas L. Wilson & Rodney O. Davis (Urbana, 2016), 103;

- Ninian Edwards, in James A. Reed, “The Later Life and Religious Sentiments of Abraham Lincoln,” Century Magazine 6 (July 1873), 338-339.

- Keyes, in Herndon & Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Lincoln, eds. Douglas L. Wilson & Rodney O. Davis (Urbana, 2006), 267; Ervin Chapman, Latest Light on Abraham Lincoln, and War-time Memories (New York, 1917), 506; “Temperance Address” (February 22, 1842) and “Speech at Hartford, Connecticut” (March 5, 1860), in CW, 1:274, 4:9; John B. Alley, in Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, ed. Allen T. Rice (New York, 1886), 591.

- Swett to Herndon (January 17, 1866), in Herndon’s Informants, 167; G.W. Pendleton, in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, ed. Michael Burlingame (Carbondale, IL, 1996), 155.

- Herndon, “To the Editor of The Truth Seeker” (December 4, 1882), in Herndon on Lincoln, 144; “Temperance Address” (February 22, 1842), in CW,1:272.

- Herndon to Truman Bartlett (August 16, 1887) and to Jesse W. Weik, in Herndon on Lincoln, 255, 259; “Conversation with O.H. Browning” (June 17, 1875), in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, 6; Max Ehrman, “Lincoln’s Visit to Terre Haute,” Indiana Magazine of History 32 (March 1936), 59-60.

- “To Mary Todd Lincoln” (June 9, 1863), in CW, 6:256. On his other dreams, see Henry J. Raymond, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York, 1865), 756, and Francis Carpenter, Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln: The Story of a Picture (New York, 1866), 292.

- Abner Y. Ellis, in Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, eds. Don & Virginia Fehrenbacher (Stanford, CA, 1996), 151; Isaac Cogdal (April 10, 1874), in B.F. Irwin, Lincoln’s Religious Belief: Original Reminiscence and Research (Springfield, 1919), 8.

- Herndon to Joseph Fowler (February 18, 1886), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 209; “To Albert G. Hodges” (April 4, 1864), in CW, 7:282; Gillespie (December 1866), in Herndon’s Informants, 506; Joshua F. Speed, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln and Notes of a Visit to California: Two Lectures (Louisville, KY, 1884), 3.

- Aminda Rankin, in Henry B. Rankin, Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln (New York, 1916), 324.

- “Hawthorne’s Complete Account of Melville in Liverpool and Chester” (November 20, 1856), in The Writings of Herman Melville: Journals, eds. Howard C. Horsford & Lynn Horth (Chicago, 1989), 628.

- “Farewell Address at Springfield, Illinois” (February 11, 1861), “Speech at Buffalo, New York” (February 16, 1861), and “Remarks at Newark, New Jersey (February 21, 1861), in CW, 4:190, 220, 234.

- Browning, in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, 5, 130; Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father (Boston 1931), 183-4.

- Isaac Cogdal interview with Herndon (1865-66), in Herndon’s Informants, 441.

- “Reply to Eliza P. Gurney” (October 26, 1862) and “Second Inaugural Address” (March 4, 1865),, in CW, 5:478, 8:332-3; Sunderland, in Reed, “The Later Life and Religious Sentiments of Abraham Lincoln,” 342-3; Browning, in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, 5.

- “Meditation on the Divine Will” in CW, 5:403-4; 8:332-3; see also John Hay, “The Heroic Age in Washington”, in At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, ed. Michael Burlingame ((Carbondale, IL, 2000), 127.

- Salmon Chase, diary entry for September 22, in Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase, ed. David H. Donald (New York, 1954), 150; Gideon Welles, diary entry for September 22, 1862, in Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson, ed. John T. Morse (Boston, 1911), 1:143; William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Reports of Lincoln’s Secretary, ed. Michael Burlingame (Lincoln, NE, 2000), 95.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln: The Story of a Picture (New York, 1867), 90; Welles, diary entry for September 22, 1862, in Diary, 1:143; Welles, “The History of Emancipation,” in Civil War and Reconstruction: Selected Essays by Gideon Welles, ed. Albert Mordell (New York, 1959), 248.

- Herndon, “To the Editor of The Liberal Age” (December 4, 1882), in Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 137.

- Stuart, in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, 15; Brooks, in Reed, “The Later Life and Religious Sentiments of Abraham Lincoln,” 340, and “How the President Took the News” (November 11, 1864) and “Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln” in Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, ed. Michael Burlingame (Baltimore, 1998), 145, 219.

- Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” (March 4, 1865) and “To Thurlow Weed” (March 15, 1865), in CW, 8:332, 356.

- Hay, diary entry for January 13, 1864, in Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, eds. Michael Burlingame & J.R.T. Ettlinger (Carbondale, IL, 1997), 142; Nicolay to Herndon (May 27, 1865), in Herndon’s Informants, 6.

- “Remarks to Baltimore Presbyterian Synod” (October 24, 1863), “To George B. Ide, James R. Doolittle, and A. Hubbell” (May 30, 1864), and “Reply to Loyal Colored People of Baltimore upon Presentation of a Bible” (September 7, 1864), in CW, 6:535, 7:368, 542.