Entertainment in Lincoln’s Springfield (1834-1860)

By Richard E. Hart

This essay is a summary of the book Entertainment in Lincoln’s Springfield (1834-1860) by Richard E. Hart and published by the Abraham Lincoln Association in November of 2017.

The public entertainments within a community are a good barometer of how its residents use their free time and what type of entertainments draw them together. In early Springfield, Illinois, on long winter nights, the folks not only enjoyed entertainment, but they also welcomed an opportunity to get out of a cooped-up winter house and pass some time with other Springfieldians in a night out of “entertainment.”

For many years while scrolling through low tech microfilm of the Sangamo Journal and the State Register, the two newspapers of Lincoln’s Springfield, I noticed advertisements for various “entertainments.” I thought that it would be interesting to collect these ads and share them with the Lincoln world, but the time to do that was something I didn’t have. Several years ago, however, techie geniuses created a new website that contained these Springfield newspapers in a searchable form—it is called GenealogyBank. (http://genealogybank.com.) I thank those techie geniuses for their contribution to historians and their gift of time that allowed me to search in this quick and easy format and create Entertainment in Lincoln’s Springfield (1834-1860).

The population of Springfield in 1830 was less than 1,000. During that decade, much of the “entertainment” was in the form of lectures by residents—Milton Hay, Dr. Anson G. Henry, Edward Baker Dickenson to name a few. In step with a national phenomenon—the creation of local lyceums—two lyceums were formed and provided a platform for Springfield men to learn and debate topics of current interest. Some of these lectures were free and open to the public. Others were open only to “members,” and sometimes in the early days women were excluded. There were occasions when women were invited to attend, but they were never invited to lecture. That honor was reserved for men. During the 1830s, the locals lectured, debated, sang songs, participated in choirs, and performed popular theatrical pieces. This was the standard fare for entertainment during the 1830s.

The earliest record of these entertainments and the first advertisement for what can be considered as “entertainment” in Springfield was for the Sangamon County Lyceum. The ad appeared in the Sangamo Journal and was dated January 4, 1834. The entertainment was to be held on Thursday evening, January 9, at the Presbyterian Meeting House and the question for discussion was Ought the General Government appropriate funds in aid of the Colonization Society? Thereafter, on most succeeding Thursday evenings during January and February 1834, the Sangamon County Lyceum met for discussions, lectures, and debates. Titles of future Lyceum lectures and debates included: Ought capital punishment be abolished? Do the signs of the present times indicate the downfall of this Government? Ought Texas to be admitted into the Union? Ought Aliens be permitted to hold civil office? Habits and foods natural to man. The Influence of poetry upon National Character.

In 1838, The Young Men’s Lyceum requested Abraham Lincoln, a twenty-eight-year-old newly arrived Springfield lawyer, to address its members. They met at the Baptist Church on Saturday evening, January 27, 1838, and Lincoln spoke on The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions. Much has been written about this Lincoln lecture. It has been scrutinized and debated by historians, who cite the lecture as a foreshadowing of Lincoln’s later public policies and addresses.[1] This is the most enduring of all the Springfield entertainments.

Here is how William Herndon, who would become Lincoln’s law partner in 1844, described the event:

…we had a society in Springfield, which contained and commanded all the culture and talent of the place. Unlike the other one [The Sangamon County Lyceum] its meetings were public, and reflected great credit on the community … The speech was brought out by the burning in St. Louis a few weeks before, by a mob, of a negro. Lincoln took this incident as a sort of text for his remarks … The address was published in the Sangamo Journal and created for the young orator a reputation which soon extended beyond the limits of the locality in which he lived.

By 1840, Springfield’s population had grown to 2,579. During that decade, as well as the preceding decade, there was no “place” dedicated to indoor performances. Entertainments were held in churches and other public places. The hall of the House of Representatives and the chamber of the Senate in the State Capitol were favorite venues after about 1844.

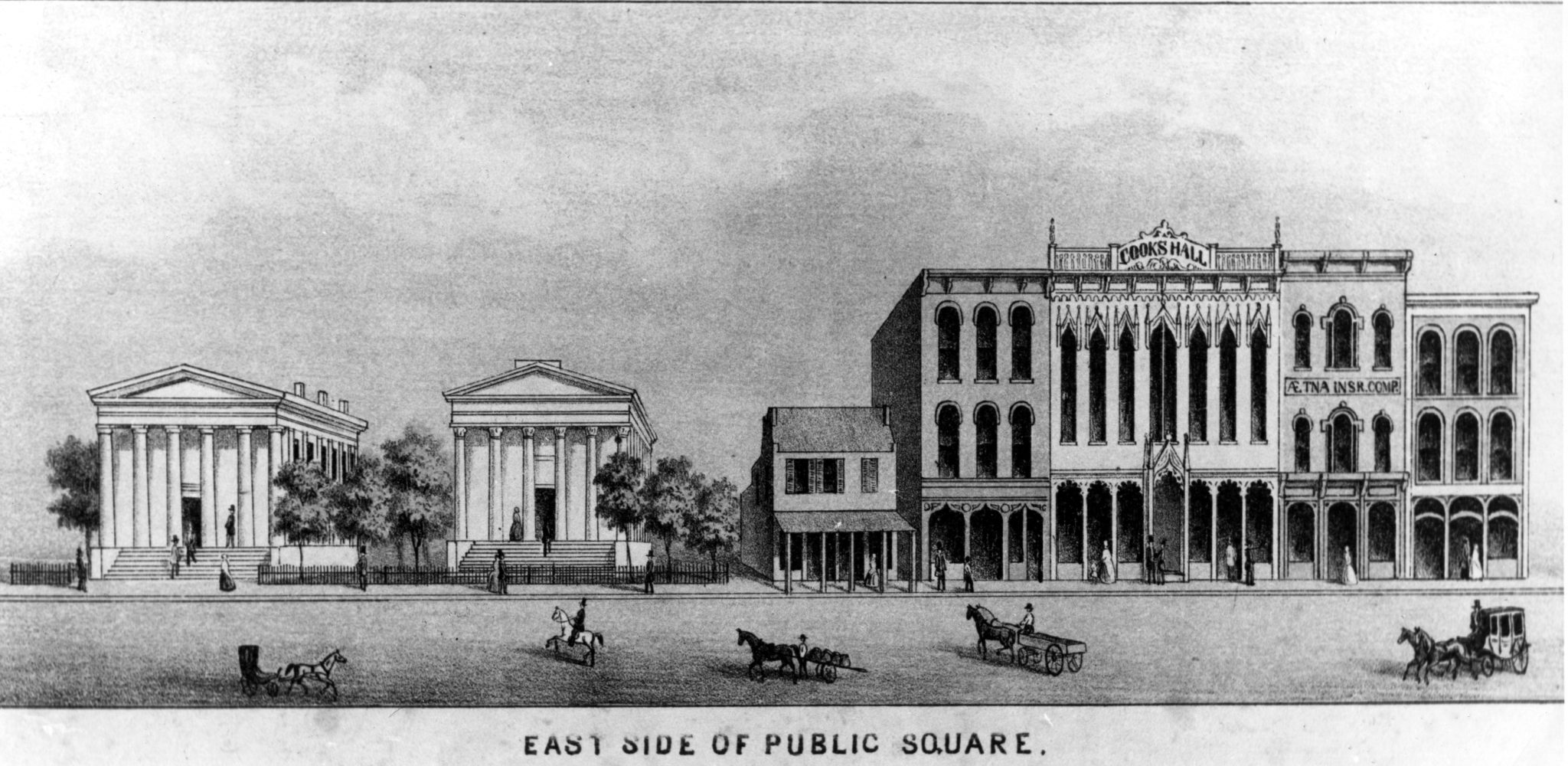

The Springfield population in 1850 had grown to 4,533. That decade saw the coming of the railroad, and after about 1853 specific places were dedicated to the commercial performing arts. These were not public places, but rather private entrepreneurial businesses. They were usually on the upper floor of a three-story building around the Public Square. There were a number of these: the Concert Hall on the north side of the Public Square, Cook’s Hall on the East Side of the Square (rebuilt after a fire in 1858), the Masonic Hall at Fifth and Monroe, Chatterton’s Hall, Clinton’s Hall, and Gray’s Saloon. When the Metropolitan Hall opened in early 1856 with 1,200 seats, it was by far the largest amusement hall in Springfield as well as in the State of Illinois.

After the February 13, 1858 fire, the east side was rebuilt with four, three-story brick buildings. One of them housed a large public hall on the second floor. It came to be known as Cook’s Hall and was a popular place for public gatherings, theatrical performances, balls and parties, and drills of the Springfield Grays.

In the 1850s, Springfield was fortunate to be on the tour route of many traveling entertainments as they moved between Chicago and St. Louis, often stopping in Springfield for a “gig.” These “entertainments” were commercial ventures requiring the purchase of tickets to be entertained by traveling artists in an astounding variety of performing arts: singers, family bell ringers, opera singers, minstrel singers, magicians, pantomimes, lecturers on a number of subjects including science and education, violin and flute concerts, holiday celebrations and balls, panoramas, readers of plays and performers of plays from Shakespeare to Irish farce, band concerts, and balloon ascensions, Fourth of July celebrations, and celebrations of the birthdays of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Robert Burns.[2]

Many of the names of those “entertaining” in Springfield are familiar to us even today. Horace Mann would be surprised to know that 150 years after his 1859 lecture in Springfield, one of the city’s principal businesses is Horace Mann Insurance. Titans in mid-nineteenth-century American political and intellectual life lectured in Springfield between 1839 and 1860 and included the following abolitionists: Samuel Hanson Cox, D.D., an “eccentric” orator who would sometimes lapse from English into Latin; Rev. Joseph Parish Thompson; Rev. Henry Ward Beecher; James Rucker; Dr. Jonathan Blanchard; Rev. John Mason Peck; Ralph Waldo Emerson; Elihu Burritt; Rev. Theodore Parker; and Joshua R. Giddings. Their lecture titles gave no indication that the speaker was an abolitionist or that the speaker might speak about abolition.

On Monday evening, January 10, 1853, Ralph Waldo Emerson gave the first of three lectures in the Hall of the House of Representatives at the Illinois State House. His first lecture was titled Wealth and The Anglo-Saxon. Orville Hickman Browning, Whig, Republican, United States Senator, and Secretary of the Interior, was present and made the following diary entries about his three evenings with Emerson lectures.

Monday January 10 At night I attended in the hall of the house, and heard a lecture from Ralph Waldo Emmerson [sic] on the Anglo Saxon. His language was chaste, strong and vigorous—much of his thought just—his voice good—his delivery clear, distinct and deliberate—his action nothing. He limned a good picture of an Englishman, and gave us some hard raps for our apishness of English fashions & manners.

Tuesday, Jany 11 1853 Heard Emmerson’s [sic]lecture in the hall of the House of Rep; upon power. He is chaste & fascinating, and whilst I cannot approve all his philosophy, I still listen with delight to his discourses. They contain much that is good, and are worth hearing.

Wednesday, Jany 12 1853 Went to Ridgleys to supper, and attended Miss Julia [Ridgley] to the State House to hear Emmersons [sic] third lecture on culture.[3]

Unlike Emerson’s name, most of the names of the entertainers are not recognized by today’s reader. Fortunately, technology in the form of Google search provides biographical information in an instant, unveiling the shadows of the past. One minstrel was said to have been Mark Twain’s model for his descriptions of minstrel shows. Another entertainer, a French ascensionist, was said to have been the aero naught for Emperor Napoleon III in the Franco-Austrian War, one year after his ascension for an astounded Springfield audience.

In the category of “she went on to become” was Fanny Raymond Ritter, America’s first female musicologist. Fanny was born sometime between 1830 and 1840, most likely in England, and died in Poughkeepsie, New York in 1891. Her father was most likely Richard Malone, an Irish entertainer who immigrated to America and toured with his daughters in a family act using the stage name Raymond.

Fanny was a young lady when she made her Springfield appearance in Abroad and at Home, a vocal concert by Malone Raymond and family—Fanny, Emily and Louisa. They appeared on Friday evening, August 29, 1851, at American House, Springfield’s finest hotel located at the southeast corner of Sixth and Adams streets, opposite the Illinois State House.

Fanny excelled as a salon musician, teacher, vocalist, and keyboardist. She was described as a fine organist and “the mistress of the German language, in the songs of Schubert, Schumann, and Robert Franz.”

Fanny was also sought after as a translator, writer, and historian. Beginning in 1859, her translations, including Wagner’s essays, were published. Her first original article appears to have been “A Sketch of the Troubadours, Trouveres, and Minstrels” for the New York Weekly Review on August 13, 1870. Fanny did original research as early as 1868 when she is credited with writing explanatory notes for her series of “historical recitals” performed at both Vassar and in New York. Many of these essays were then compiled in a book entitled Lyre, Pen, and Pencil published in 1891.11 Her efforts culminated in the translation of Robert Schumann’s Gesammelte Schriften und Texten published in book form in 1876.

One of Fanny’s most significant essays, Woman as a Musician: An Art-Historical Study was written in 1876 for the Centennial Congress of the Association for the Advancement of Women. Fanny’s essay was the first specifically musical writing of its kind and as such was a catalyst for dialogue in American musical circles concerning women’s place in music.

Some of the itinerant entertainers were scoundrels, leaving unpaid advertising bills from their local stay. One soprano had been the former wife of the King of Bavaria and the mistress of many European notables. When she lectured on “fashion,” William Herndon did not like that at all. He lectured the night following her appearance, scolding those who had attended and lecturing all on the general decline in community standards.

But, the most interesting, salacious tidbit from all of the entertainments involved a pianist, Sigismund Thalberg. He had been decorated by every European potentate. While touring Illinois, the mother of a young member of Thalberg’s troupe shot at him for “fiddling” with her daughter. The report is that Thalberg quietly left Illinois and headed back to Europe on the sly and in disgrace.

The saddest story involves a young boy named Nicholas Goodall, a flute player genius. Nicholas appeared at the Masonic Hall in Springfield on February 21, 1855. He was wildly popular and extended his Springfield stay. He was even invited to parties in private Springfield homes. There is no evidence to put Abraham Lincoln at any of his concerts, but he was in Springfield during this time and may have attended.

On the evening of April 14, 1865, Nicholas was purported to have been present at Ford’s Theatre where his father was first violinist in the orchestra. It is said that young Nicholas witnessed the assassination of Lincoln and thereafter fell into a hopeless depression. His father placed Nicholas in an institution for the insane. Nicholas lived there and in the local alms house until his death at age thirty-two in 1881.

No doubt Abraham Lincoln attended some of these entertainments during his residency in Springfield from April 1837 to February 1861. He loved Shakespeare and the theater. There were a number of performances of that sort that he may have enjoyed—Mr. Emmett, reading Othello and Richard III, Mr. Boothroyd reading Shakespeare, Mrs. Macready reading scenes from Macbeth, Charles Walter Couldock reading Macbeth, Miss M. Tree reading Hamlet, and Rev. Henry Giles lecturing on Women of Shakespeare.

Abraham Lincoln most likely attended several of the Springfield entertainments. Entertainment in Lincoln’s Springfield notes the dates when Lincoln was in Springfield and could have possibly attended entertainments. The amazing fact, however, is that some of the entertainments that appeared in Springfield later appeared in Washington, D.C., and were attended by President Lincoln. Perhaps he also saw the entertainment in Springfield as well.

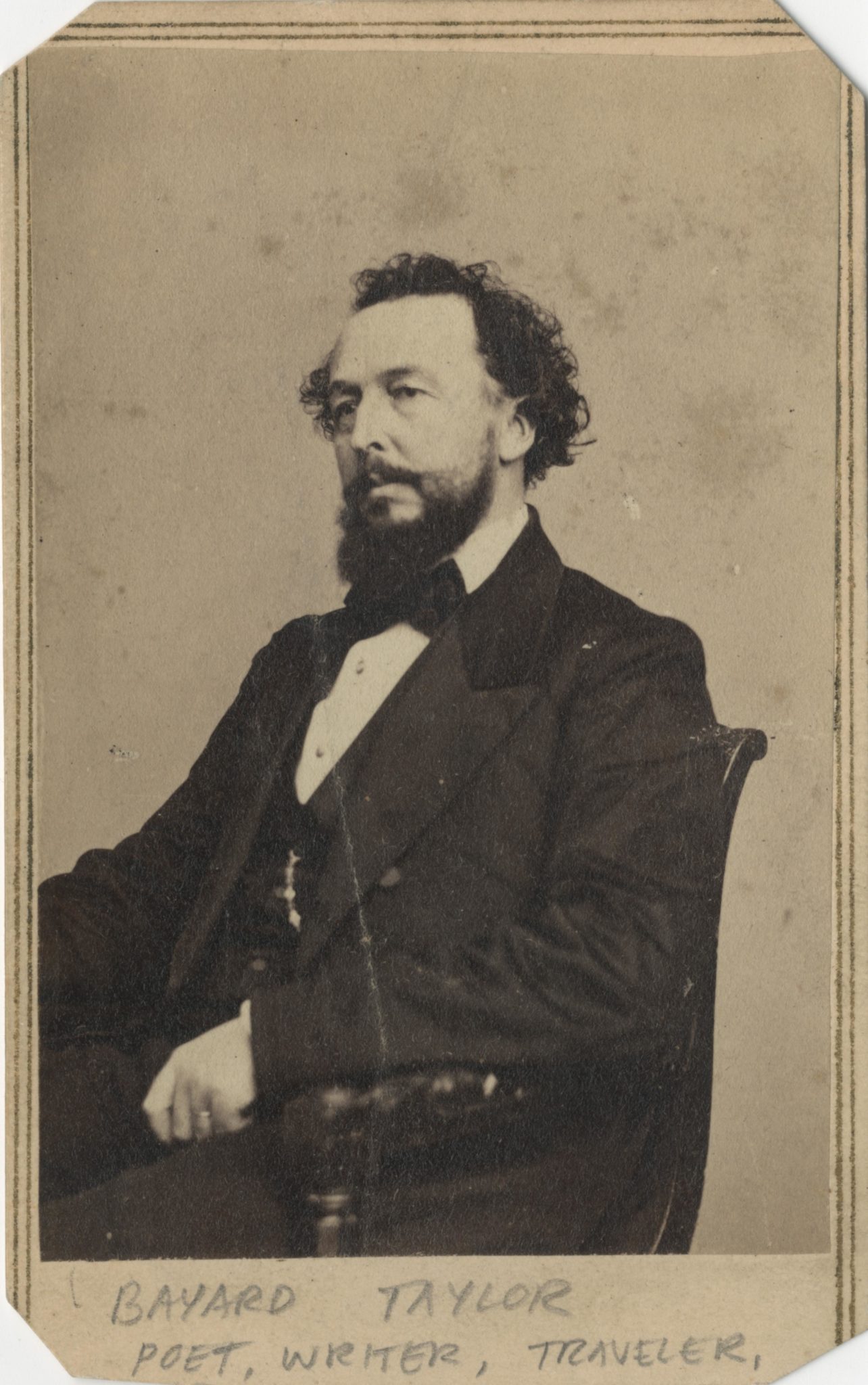

Bayard Taylor was one of those who appeared in Springfield and Washington. Taylor gave three lectures in Springfield on Monday, Friday, and Saturday, March 12, 16, and 17, 1855. He spoke in Metropolitan Hall, which seated 1,200, at the invitation of the Young Men’s Christian Association. He charged twenty-five cents for an attendee to hear him speak on Japan, India, and The Philosophy of Travel. Abraham Lincoln was in Springfield.

Taylor arrived in Springfield in a driving rain and found the town a mud hole. In 1859, he published his impressions in the first volume of At Home and Abroad. There he wrote:

I must do Springfield the justice to say that it has its sunshine side, when the mud dries up with magical rapidity and its level streets become fair to look upon. The clouds cleared away on the morning after my arrival, and when my friend, Captain Diller, took me to the cupola of the State House and showed me the wide ring of cultivated prairie, dotted with groves of hickory, sugar-maple, and oak, which inspheres the capital of Suckerdom, I confess that it was a sight to be proud of. The young green of the woods and the promising wheat-fields melted away gradually into blue, and the fronts of distant farm-houses shown in the morning sun like the sails of vessels in the offing. The wet soil of the cornfields resembled patches of black velvet—recalling to my mind the dark, prolific loam of the Nile Valley.

In 1862, during the administration of President Lincoln, Taylor entered the United States diplomatic service as Chargé d’Affaires under the minister to Russia at St. Petersburg. On Friday, December 18, 1863, Bayard gave a lecture on Russia at Willard’s Hall, in Washington, D.C. President Lincoln attended the lecture and a week later suggested to Bayard that he prepare a lecture on “Serfs, Serfdom, and Emancipation in Russia.”

Lincoln’s Springfield was indeed a small town on the western frontier of the United States. Such or similar descriptions have led many to assume that it was a backwater, a sleepy, uninvolved, intellectually barren place. Young John Hay, the recent class poet at Brown University, wrote to his friend back east that there was not much going on in Springfield and not anyone worth talking to. Abraham Lincoln’s office was next door. Such are the errors of youthful perception.

To the contrary, Springfield was home to a vast array of interesting entertainments. From 1834 until the end of 1860, there were over three hundred entertainments given in at least twenty-two separate Springfield venues. While minstrel shows are offensive by today’s standards, most of the other entertainments are similar to those that remain current today. They would not be found in the popular culture of our time, but rather they would be classic fodder for PBS, National Geographic history programs, or today’s performing arts centers. They would find it hard to compete with today’s popular movie and television culture, and that speaks highly of the entertainments of Lincoln’s Springfield!

Richard Hart is an attorney in Springfield, Illinois, and a member of the Board of Directors of the Abraham Lincoln Association.

[1] The full text of the speech may be found in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 1, pp. 108-115.

[2] There were other forms of entertainment: circuses, the annual state fair when it was held in Springfield, and a slew of dancing classes. None of these are covered in this study. See the author’s Circuses in Lincoln’s Springfield (2013).

[3] The Diary of Orville H. Browning, 1850–1881 (2 vols. ed.), Springfield, Illinois, Illinois State Historical Society.