Douglas L. Wilson Discusses Herndon on Lincoln: Letters

An Interview with Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Please explain the purpose of this excellent and thought-provoking book and how it relates to your other publications about William H. Herndon.

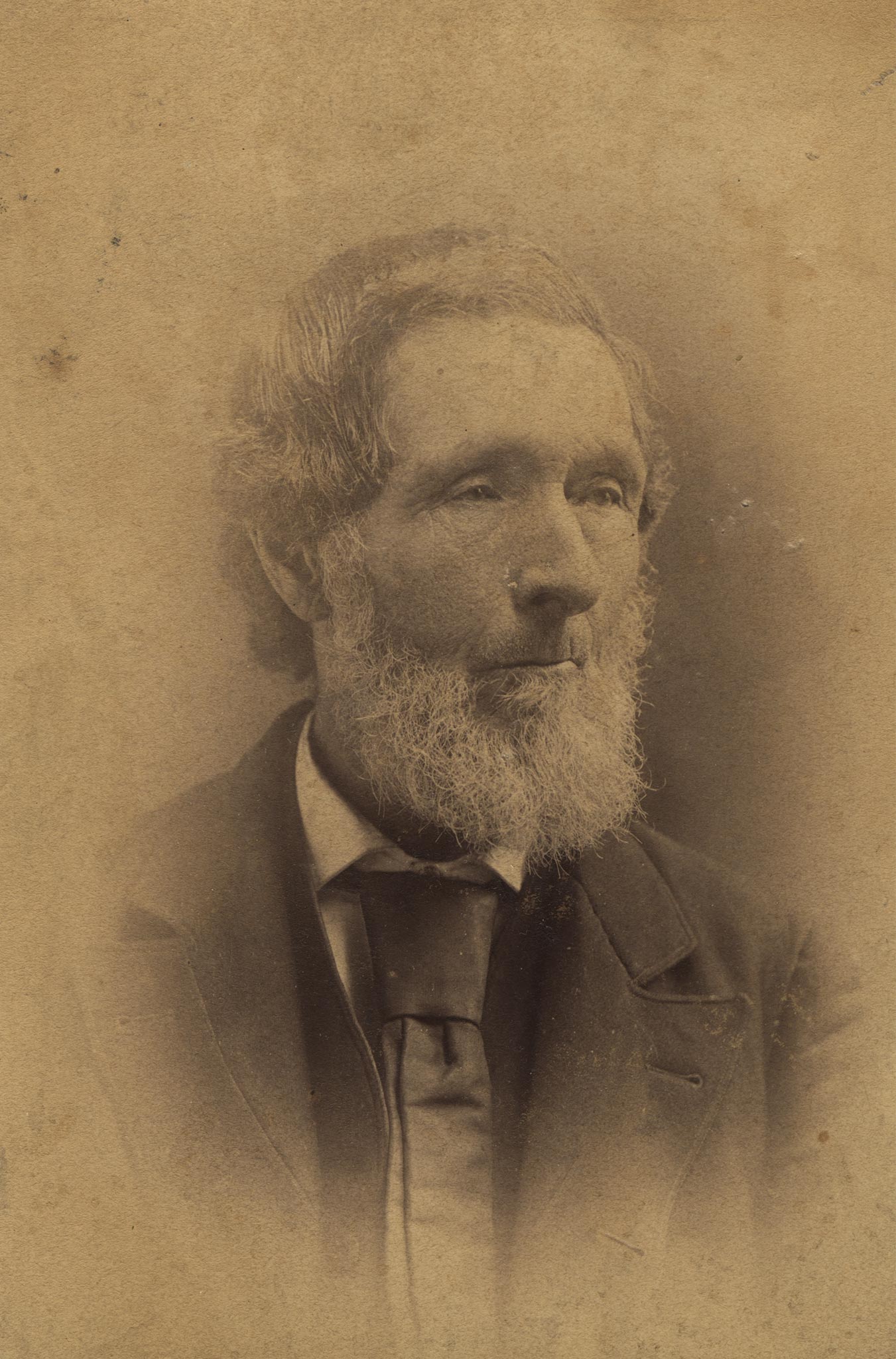

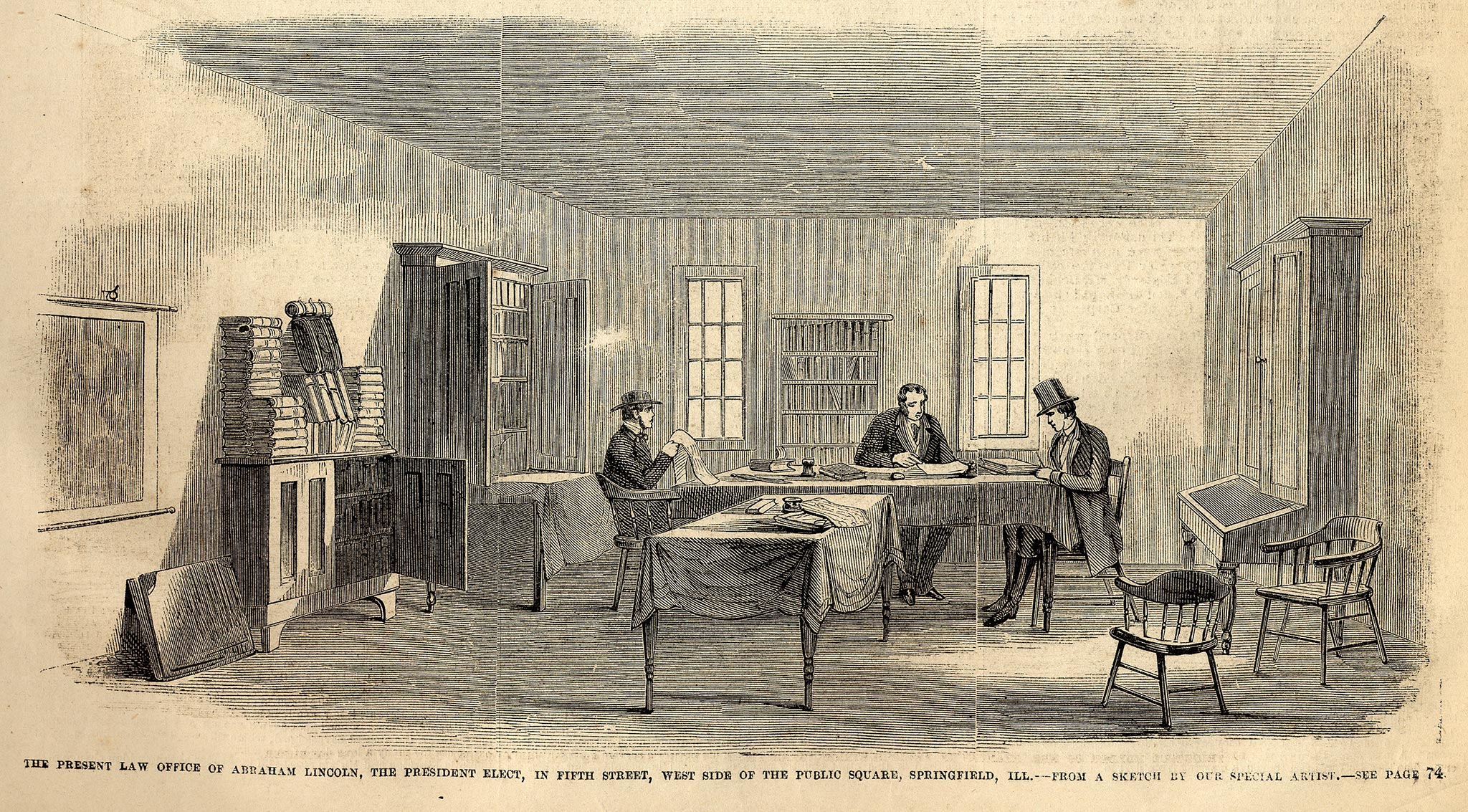

Douglas L. Wilson: There are several reasons why a collection of William H. Herndon’s letters on Lincoln is needed. To begin with, as Lincoln’s law partner, Herndon was known to have worked more closely with Lincoln than any other person except his wife. Ostensibly, this afforded Herndon an almost unique intimacy with Lincoln, whom his friends knew to be markedly secretive and unconfiding. Herndon himself thought he knew Lincoln very well, but he also confessed on many occasions that he was often unable to penetrate Lincoln’s inveterate privacy. The student of Lincoln soon learns that Herndon is often quoted on the first side of this equation, but rarely on the second. The reader of his letters soon learns that it is the latter that is the most frequently expressed and seems, in general, to have been the prevailing sentiment. Nonetheless, Herndon did know Lincoln extremely well by almost any measure, and this is the principal reason that his letters about Lincoln are noteworthy.

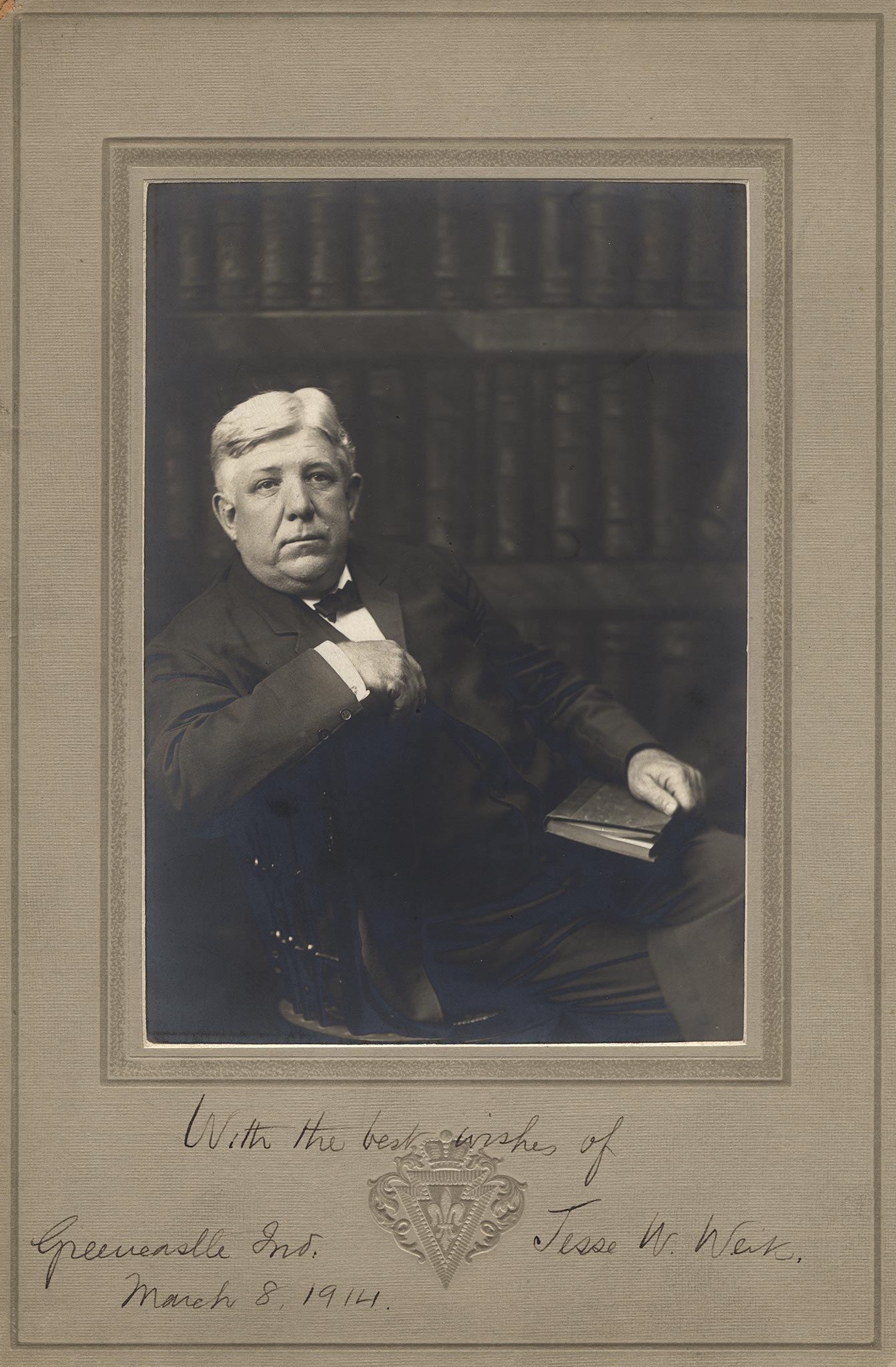

Another reason that Herndon’s letters about Lincoln are important is that they provide a very significant corrective to the views expressed in Herndon’s Lincoln, which Don E. Fehrenbacher in 1996 called “the most influential biography of Lincoln ever published.” Herndon famously gathered information for this book most of his life, but while it is written in the first person as though told by Herndon himself, it was actually composed almost entirely by a collaborator, Jesse W. Weik.

This would be one thing if the views of Lincoln were in all cases closely based on Herndon’s own, but such is not the case. For reasons too complicated to describe here, Herndon lost control of both the design and the content of the work, with the result that many things that Herndon originally intended to emphasize were muted or left out altogether. A conspicuous example of the differences between Herndon and his collaborator, Weik, appears in the treatment of Lincoln’s fatalism. Herndon believed it was the most important aspect of Lincoln’s intellectual makeup that the public knew nothing about, and he wrote about it repeatedly and extensively in his letters. This idea, however, did not comport with Weik’s more smiling picture of Lincoln, so that in the narrative he composed for the biography, fatalism is included in a listing of Lincoln’s “absurd superstitions.” It must be said, however, that some of the omissions were actually authorized by Herndon himself, who, at the time the book was being completed, was desperately poor and ill and admitted he sought to avoid including details that would offend or alienate readers and hurt the sales of the book. Considerations like these suggest the wisdom of David Donald’s longstanding verdict that “To understand Herndon’s rather peculiar approach to Lincoln biography, one must go back to his letters.”

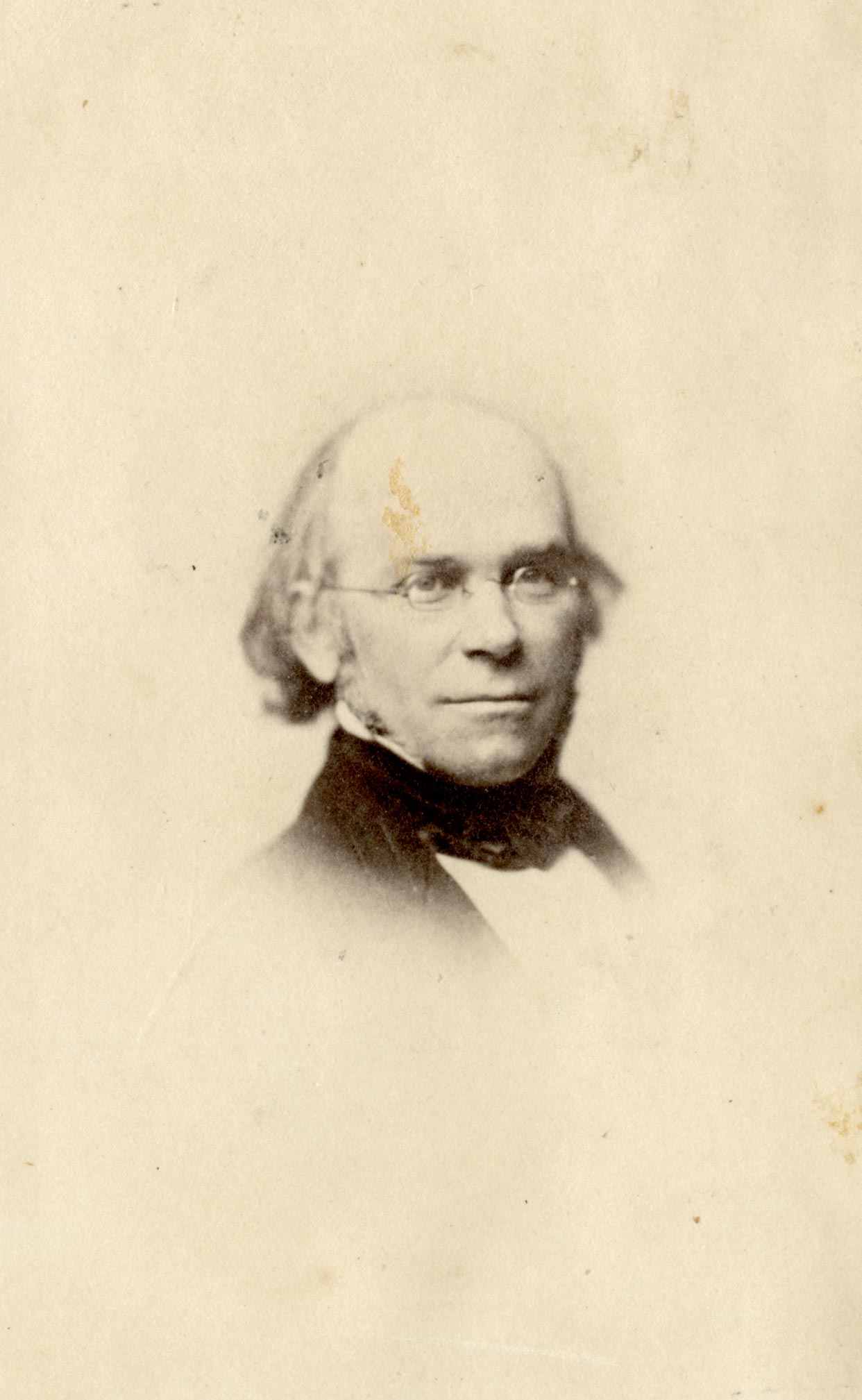

SG: You report on several 1858 letters from William Herndon to Theodore Parker. Please comment on Parker’s participation in the transcendentalist movement and on Herndon’s relationship with him.

DLW: Theodore Parker was a highly regarded Boston minister whose enlightened sermons and other writings made him one of the bright lights of the American transcendental movement. Herndon, from an early day, corresponded with many of the writers whose works were featured in the books and magazines of his time—Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, to name a few—and as this list suggests, he was especially eager to have personal contact with the most noted abolitionists. Theodore Parker was one of these, and Herndon’s exchange of letters with Parker was quite substantial. Most of this correspondence was characterized by Herndon’s seeking enlightenment from these notables, but when Herndon’s law partner became a nationally recognized politician, these correspondents sought information about Lincoln from Herndon. These are the sorts of letters that appear in our book, Herndon on Lincoln: Letters. Parker was a talented thinker and graceful writer and, but for his early death just prior to Lincoln’s election as president, would have been more prominent in the political ferment precipitated by slavery. Herndon is credited with loaning Lincoln the printed text of one of Parker’s lectures, which contained a sentence that may have served as the inspiration for the famous ending of the Gettysburg Address: “Democracy is direct self-government, over all the people, for all the people, by all the people.”

SG: An interesting letter to Caroline Healy Dall on November 10, 1861, seems to articulate the belief that President Lincoln was not acting swiftly enough in efforts to rid the country of slavery. A letter to the same woman on January 28, 1862, provides evidence of Herndon’s disapproval of Mary Todd Lincoln, calling her “curious, Eccentric, and wicked.” Who was Caroline Healey Dall and why was Herndon so outspoken in letters to her which appear throughout your book?

DLW: Caroline Healy Dall was a Boston feminist and reformer who sought help from Herndon in 1860 when working on a book, Woman’s Rights Under the Law (1862). They continued to correspond about Lincoln after he became president. Dall was notoriously cranky and hard to please, but she eventually came to admire Lincoln’s work as president and supported him when her better known feminist friends, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, worked to keep him from getting a second term. Herndon and Dall were certainly birds of a feather on the subject of Lincoln’s apparent lack of movement as president against slavery.

Dall became interested in writing about Lincoln, and while staying in Herndon’s home on a visit to Springfield in 1866, read through the extensive Lincoln archive Herndon had collected, including two memorandum books in which he kept notes of some of the most sensational information he was given by his informants. Dall was shocked by what she read and formed some false impressions that Herndon could never persuade her to change. At the time when Herndon’s lecture about Lincoln and Ann Rutledge came under heavy fire in 1866, Dall wrote a much-reprinted newspaper letter defending him, and she also published a positive article about his Lincoln researches in the Atlantic Monthly in 1867.

Herndon’s letter to Dall expressing strong disapproval of Mary Todd Lincoln was written soon after he returned from his only trip to Washington during his law partner’s presidency, where the devious behavior of the president’s wife was currently the talk of the town. Mary Todd Lincoln’s biographers have tended to play down her White House misadventures, but Michael Burlingame has laid them out in detail in an appendix to his book At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings. They have recently been candidly put on display in James B. Conroy’s Lincoln Prize winning book, Lincoln’s White House: The People’s House in Wartime.

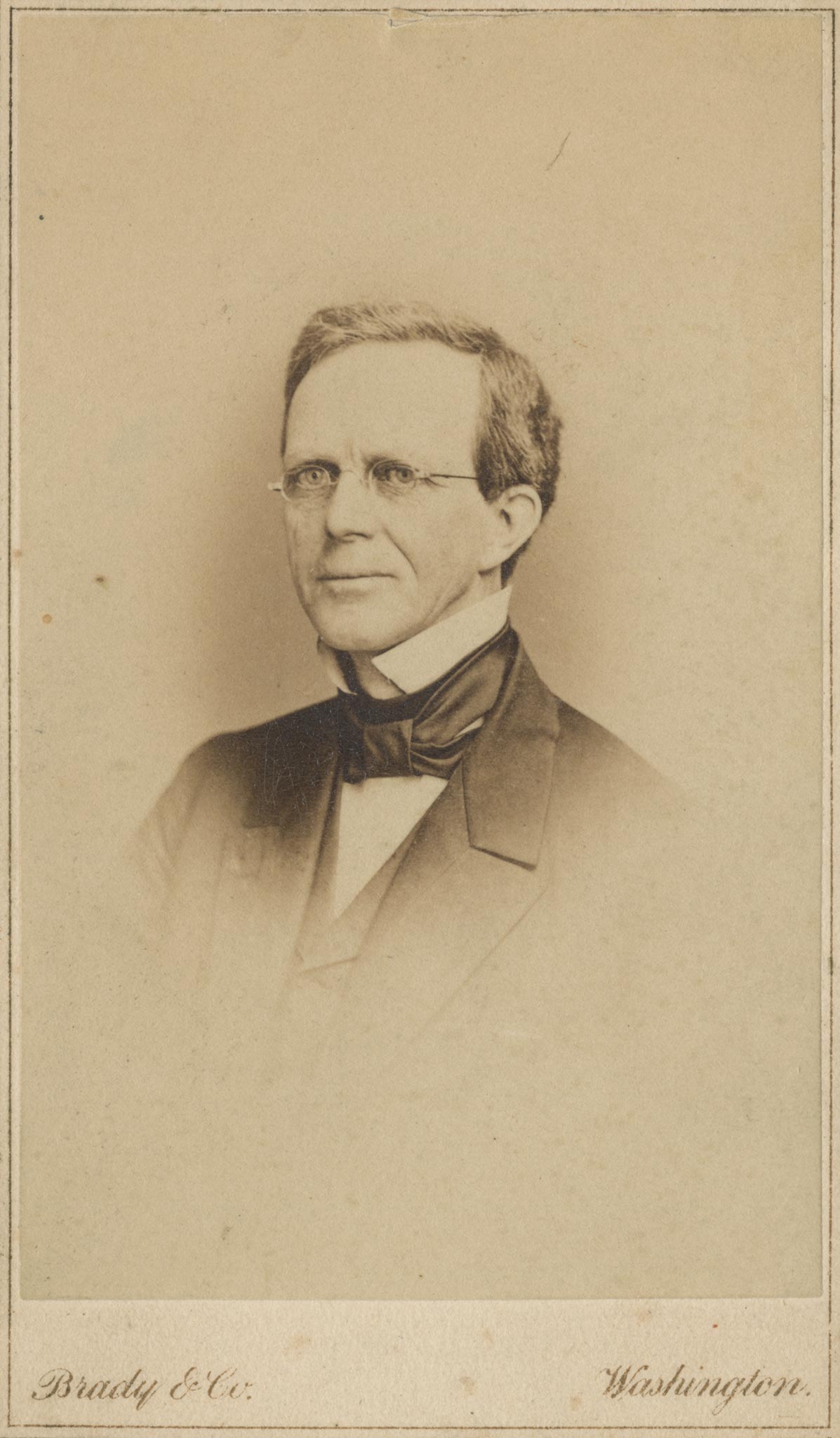

SG: On the same point as above, the letter to Lyman Trumbull on November 20, 1861, gives an even stronger (and perhaps angrier) criticism of the President’s reluctance to use more than “pop guns filled with rose water” to attack slavery. Would you put Herndon in the ranks of the radical abolitionists?

DLW: Herndon considered himself every inch an abolitionist, but living at a time and place where advocating abolition was very unpopular and bound to alienate a good many of his friends and clients, he was a relatively well-behaved one. So while he himself and others may have considered him a radical, he didn’t indulge in the kind of insistent and in-your-face advocacy that the term “radical abolitionists” brings to mind. By contrast, Lincoln was always anti-slavery but never an abolitionist, although his chief antagonist, Stephen A. Douglas, tried very hard to convince their audiences that he was. Lincoln argued that slavery was inconsistent with democracy and would eventually have to go, but he was inherently a gradualist, cautious about getting ahead of the electorate. In this light, it was to be expected that Herndon could complain to Senator Trumbull about Lincoln’s reluctance to move decisively against slavery because Trumbull, like many other Republican senators, agreed with him.

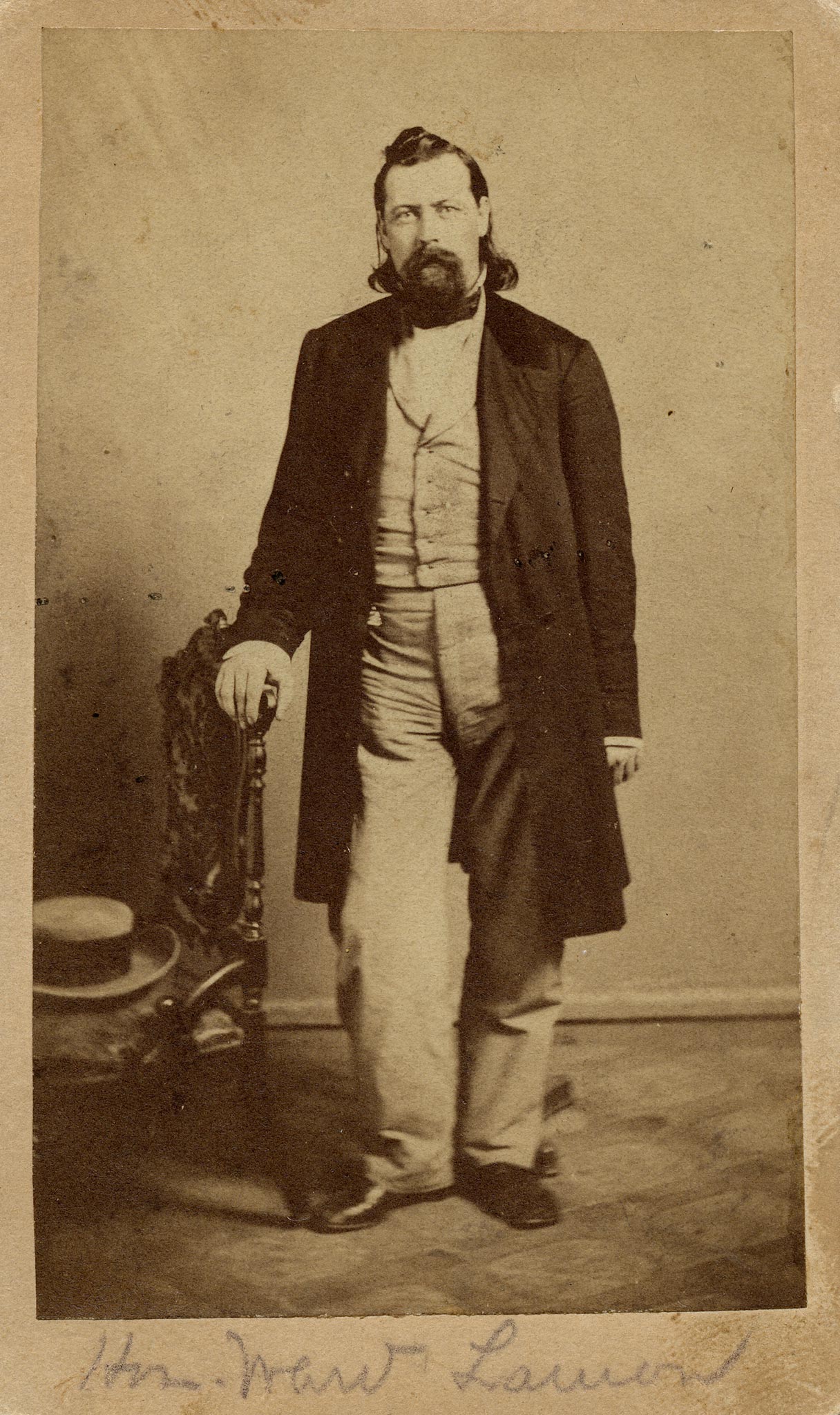

SG: A letter to Ward Hill Lamon on June 12, 1865, states that Herndon is “writing the life of Lincoln.” Please comment on the type of information he requests.

DLW: Herndon begins that letter by asking Lamon to send him “the wall paper life of Lincoln that O. M. Hatch loaned you,” but we were unable to discover what this referred to. The rest of the letter, which was written soon after Herndon had decided to write a biography of his former law partner, constitutes a very useful list of the kind of information he was most anxious to acquire. He focuses attention on Lincoln’s behavior in the White House, where he had no opportunity to observe him. Lamon was a lawyer on Lincoln’s circuit who was given a presidential appointment in Washington and was closely associated with Lincoln as president. Herndon’s letter shows that he was hoping Lamon would prove a likely source for the unorthodox kinds of details he was in search of: “Please sit down & tell me what Mr Lincoln loved to Eat — what 3 or 4 things he loved best — How he acted about the White House — his habits, customs — Modes — Manners & times of doing what he did — privately — socially & politically &c. &c.” These are things that Herndon delighted to write about in his letters and lectures from his own observations, and it is clear from this letter that he wanted to learn if Lincoln behaved differently in the White House. It is also clear in this letter (and elsewhere) that he scorns reports that Lincoln took a different view of religion in Washington from what he professed in Springfield. No reply to this letter is known, but notes on an interview with Lamon taken later contains responses to some of the queries in this letter. (See Herndon’s Informants, pp. 466-67.)

SG: What is the genesis of Herndon’s apparent antipathy toward Mary Lincoln? Was there a change in his willingness to voice his opinions after the assassination?

DLW: For those who are interested, I have written a documented narrative of the history of this relationship entitled “William H. Herndon and Mary Todd Lincoln” that was first published in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association in 2001 and reprinted in 2012 in The Mary Lincoln Enigma, edited by Frank Williams and Mike Burkheimer. The short version of the story is that in 1948 David Donald called attention to an anecdote in Herndon’s Lincoln about Herndon’s having danced with Mary Todd soon after she arrived in Springfield and having unintentionally offended her with an expression he awkwardly offered as a compliment. Donald concluded that “Neither ever forgot that episode” and that it marked the beginning of a lifelong antagonism between them. This idea was duly adopted by writers about Lincoln as an established fact and ultimately served as the basis of the widespread belief that Herndon actually hated his partner’s wife from their earliest acquaintance. Although these charges are based on Donald’s conclusions, Donald himself was clear that he was merely speculating, for he admitted that there was no evidence for a long-standing antagonism. “So far as can be judged from existing evidence,” Donald wrote, “during Lincoln’s Springfield years Herndon and Mary maintained restrained, if distant, relations.”

This has proved an important point in Lincoln studies for the reason that Herndon has been so deeply involved in the presentation of so much of what we know about his law partner. The idea that Herndon hated Mary Lincoln has suggested to many commentators the likelihood that Herndon, out of malice, deliberately set out to present a biased and unfair picture of her, and thus of his law partner’s married life.

In December 1865 Herndon began a series of public lectures on the subject of Abraham Lincoln, in the first of which he was reported as saying, “I do not think he knew what real joy was for more than twenty-three years.” Even if the reference escaped most newspaper readers across the country, his Springfield audience knew at once that “twenty-three years” referred to the period of the Lincoln marriage. It is doubtful that Mary noticed this reference, for in August of the following year she wrote to Herndon to flatter him that he was “cherished with the sincerest regard by my sons & myself,” and to invite him to meet with her when she traveled the following week to Springfield. At this meeting, which seems to have been entirely amicable, she gave Herndon one of the most valuable interviews he got about her husband’s behavior in Washington.

But then came what Donald called the “open rupture” of their relationship. A few months later Herndon delivered a sensational public lecture that featured his prize discovery, the young Lincoln’s love affair with Ann Rutledge. He startled his audience by saying at the beginning of the lecture, “Lincoln loved Ann Rutledge better than his own life,” but he effectively sealed his fate by saying later on: “[Lincoln] never addressed another woman, in my opinion, ‘yours affectionately;’ and generally and characteristically abstained from the use of the word ‘love.’” From that time on, Mary Lincoln made it abundantly clear that she hated him. Herndon’s only defense of heedlessly humiliating the grieving widow of a martyred President was that this was a truth that was necessary to an understanding of Lincoln’s experience and his subsequent melancholy character, but it earned him a degree of acrimony that was unremitting and has lasted in some measure down to the present.

But strangely enough, we learn from his letters that he continued to insist that Mary Lincoln was not the only party at fault for the difficulties in the Lincoln marriage, that she had much to contend with, and that she lacked the temperament to bear her burdens with a becoming restraint. Herndon certainly believed that Lincoln was forced into a loveless marriage and that his domestic life was very trying, and he wrote about these things because he thought they mattered in understanding him. After his Ann Rutledge lecture in November 1866, Mary Lincoln definitely exhibited something that could be called hatred for Herndon, on grounds that most observers find very understandable. But I confess that I have never found any conclusive evidence that Herndon ever harbored or professed hatred for Mary Lincoln.

SG: What efforts did Herndon make to solicit information about Lincoln’s youth in Indiana? What is your impression of the effect of those years on the future president?

DLW: In September of 1865, a few months after he began his investigation of Lincoln’s early life, Herndon visited the neighborhood in southwest Indiana where Lincoln grew up and interviewed many of his surviving neighbors. In these interviews and in succeeding correspondence, he solicited and assembled the most revealing body of information we have on Lincoln’s boyhood and young manhood, covering everything from his early reading and writing to his flatboat trip to New Orleans. There are other sources of information about Lincoln’s Indiana years, but it is the accounts collected by Herndon that underlie our understanding of how Lincoln was recognized by those who knew him from boyhood as an exceptional person with talent and ambition.

The effect of Lincoln’s Indiana years, from the age of seven to twenty-one, on the person who would become the nation’s greatest president is, of course, a speculative matter. In studying the materials Herndon collected, I felt immediately that his experiences growing up resonated with the man he became. The most incisive pieces of testimony for me have been those that bear witness to Lincoln’s early and extraordinary interest in both reading, which is part of the legend, and writing, which is not. His former friends and neighbors in Indiana laid the basis in their letters and interviews with Herndon for Lincoln as an eager reader of books, but his stepmother told Herndon about his practice of writing out notes on his reading in a kind of literary notebook. She also described to Herndon the pains the young Lincoln took with words, especially words he came across in his reading that were unfamiliar, about which he compulsively sought clarity as to their meaning and their use. If he came across a word that he couldn’t understand, he wasn’t satisfied until he had learned its meaning and how to use it properly in a sentence. We can be reasonably sure that this experience stayed with him and contributed to his gift for clarity of expression, for he described this very phenomenon in 1860 to someone who complimented him on the clarity of a speech he had given.

SG: Was there a difference in subject matter and approach between Herndon’s written comments on Lincoln’s life and those points which he chose to articulate in lectures?

DLW: This question is of particular interest to me at this time, as my partner, Rodney O. Davis, and I are currently preparing an edition of Herndon’s other writings about Lincoln that will include all existing texts of his lectures on Lincoln, including one that was never finished on his early development in Kentucky and Indiana. These surviving lectures on Lincoln are rife with descriptions of Lincoln’s person, his attitudes, quirks, behavior, temperament, habits, likes, and dislikes. He has much to say about Lincoln as a practicing lawyer, specifying where he excelled and where he was weak. Herndon also emphasizes that, much as Lincoln’s social demeanor was regarded as warm and open-handed, he was actually an unusually private and even secretive person, who rarely yielded a glimpse of his innermost views or concerns.

Herndon’s first lecture on Lincoln is especially notable for its concentration on Lincoln’s distinctive mindset—his basic attitudes and ways of thinking, his particular intellectual interests, as well as what didn’t much interest him, his penchant for getting at the very essence of a question or issue. Here Herndon is free to indulge his own theories about the supposed relationship between physiology and mental makeup, which his collaborator Weik tried to keep out of Herndon’s Lincoln. Sometimes Herndon can sound like a crank or a quack, but at other times he can sound like a prophet. For example, in trying to explain what he called Lincoln’s “double consciousness”—his ability to shift rapidly from a state of melancholy absorption to one of animated good humor. Herndon’s suggestion was that this phenomenon “may spring out of the double brain . . . one life in one hemisphere of the brain and the other life in the other.” (338) This, too, may have sounded farfetched to Herndon’s contemporaries, but it becomes more plausible in an age that is transfixed by the concept of differing functions being assigned to the right and left brain.

One of the attractions of these lectures, which are not widely consulted or even well known, is that Herndon is speaking in his own voice, as opposed to what one gets from the biography, Herndon’s Lincoln, where the first-person narration attributed to Herndon was actually the work of Jesse Weik. And I have always thought that there is an added interest in these lectures inasmuch as they were written, not for general publication, but to be delivered to live audiences comprised of people who were not strangers to Abraham Lincoln but rather his Springfield friends and neighbors, who knew him well.

Douglas L. Wilson is the George A. Lawrence Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English and co-director of the Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College.