Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Standing Lincoln: A Biographical Monument to Abraham Lincoln and its Legacy

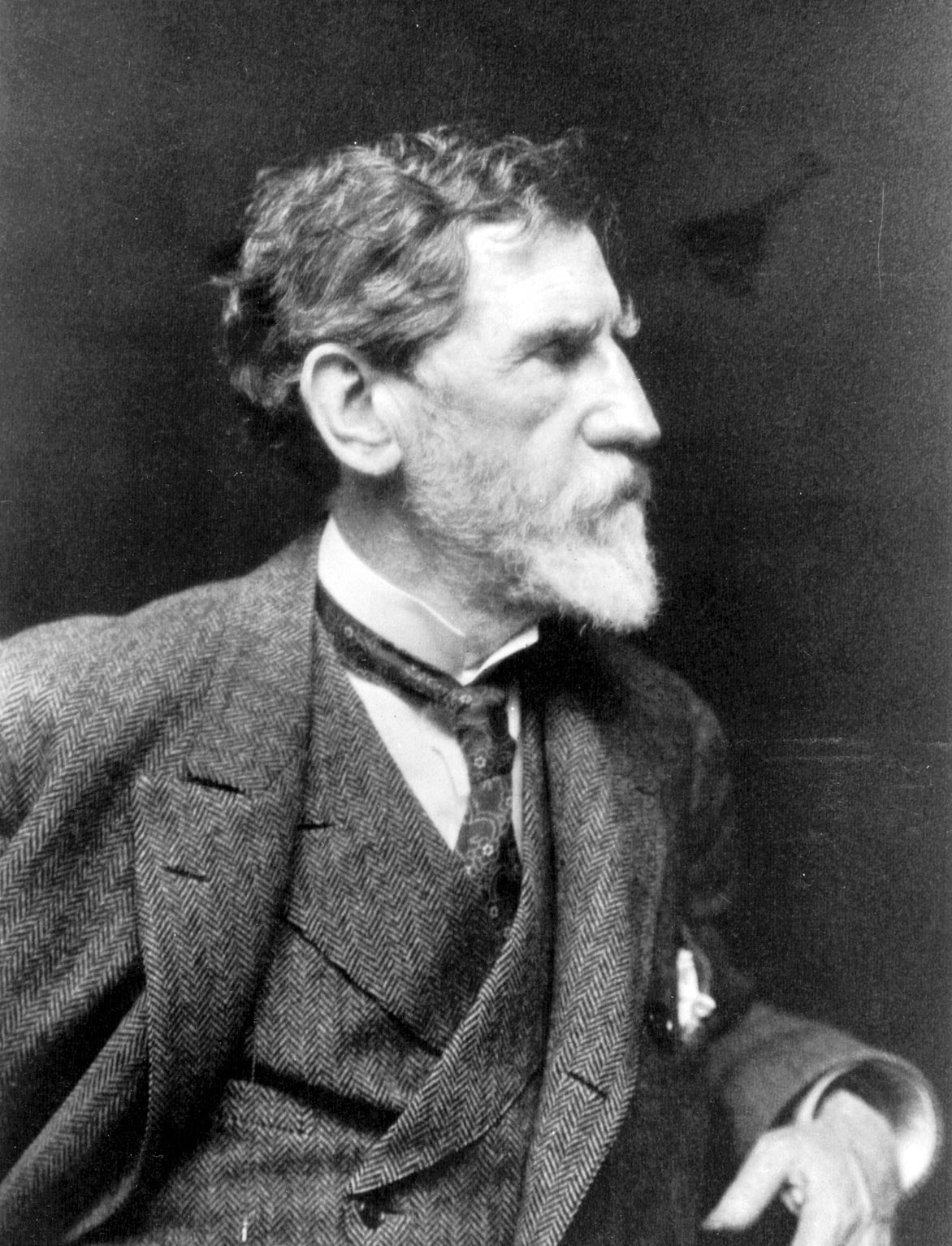

In a one-hundred-year-old barn in Cornish, New Hampshire, Augustus Saint-Gaudens reshaped the memory of Abraham Lincoln in sculpture as he spent months turning blocks of clay into the 16th President of the United States. With his 1887 sculpture, Abraham Lincoln: The Man, commonly known simply as Standing Lincoln, Saint-Gaudens redirected the legacy of Abraham Lincoln in sculpture away from a romanticized Lincoln to a simplistic and naturalistic statesman, preparing to speak before an audience as he so often did. Immediately following the death of Lincoln, sculptors and patrons of the President sought to preserve his legacy in bronze and marble, beginning with many romanticized images of the slain President. Using research and personal recollections of Lincoln, Saint-Gaudens created a Lincoln recognizable by the public, not a hagiographic figure, as he relied on Lincoln biographies for artistic themes. Saint-Gaudens’s Abraham Lincoln: The Man redefined the interpretation of Abraham Lincoln in sculpture, influencing the memory and legacy of Lincoln in sculpture by reflecting numerous biographical themes of the 16th President.

It was in New York that Saint-Gaudens had his first encounters with the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln. In his youth, Saint-Gaudens experienced the “great visions and great remembrances; the political meetings; the processions before the Presidential election, with carts bearing rail-fences in honor of ‘Honest Abe, the Rail-Splitter.’”1 He read newspapers of the great battles of the Civil War, and watched soldiers pass through the city, but one image stood in his mind above all others. Saint-Gaudens, years following the Civil War, wrote:

But, above all, what remains in my mind is seeing in a procession the figure of a tall and very dark man, seeming entirely out of proportion in his height with the carriage in which he was driven, bowing to the crowds on each side. This was on the corner of Twentieth or Twenty-first Street and Fifth Avenue, and the man was Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington. Perhaps it is the flight of time that makes this and all the rest seem much more heroic and romantic than the extraordinary events of our age. 2

In 1865, Augustus Saint-Gaudens received news of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth. In his Reminiscences, Saint-Gaudens recalls this period of his life by writing:

I recall father and mother weeping, as he read of [the assassination] to us the morning at breakfast, before starting for work. Later, after joining the interminable line that formed somewhere down Chatham Street and led up by the bier at the head of the staircase, I saw Lincoln lying in state in the City Hall, and I went back to the end of the line to look at him again. This completed my vision of the big man, though the funeral, which I viewed from the roof of the old Wallack’s Theater on Broome Street, deepened the profound solemnity of my impression, as I noticed every one uncover while the funeral car went by.3

Saint-Gaudens witnessed the funeral procession of the body of Abraham Lincoln on April 24, 1865, as the casket was paraded down the streets of New York. The young sculptor passed in silence to view the slain President, viewing the body at a point on the funeral train where Lincoln no longer looked natural as many thought the body looked “grotesque, the skin discolored, the eyes and cheeks sunken.” 4

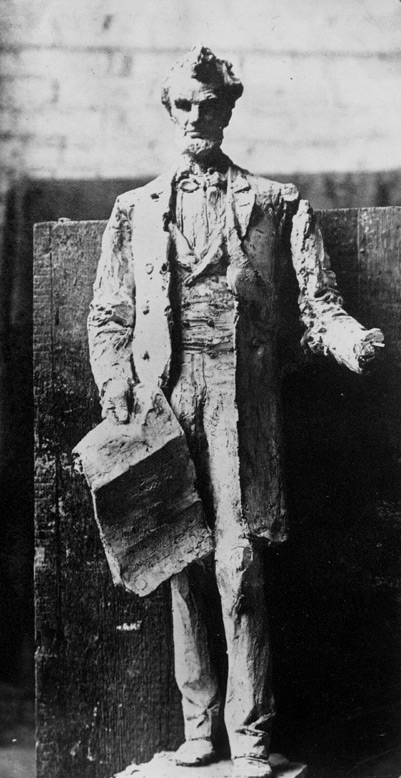

On November 11, 1884, Augustus Saint-Gaudens signed a contract with the Lincoln Monument Fund, agreeing to “execute a full length statue of Abraham Lincoln former President of the United States” to stand on a granite pedestal.5 Saint-Gaudens accepted the commission, immediately beginning work on the piece, conceptualizing the personification of Lincoln he would put to bronze. In 1885, to escape the heat and stress of New York City, Saint-Gaudens rented a home in Cornish, New Hampshire, which he would eventually purchase and live full-time. To convince the sculptor to move to New Hampshire, Saint-Gaudens’s friend Charles Beaman, promised “plenty of Lincoln shaped men” in the area, a claim that held true for when Saint-Gaudens began work on the Lincoln, he found it easy to find a model for his work.6

As he made his move to his new home and studio for the summer in Cornish, Saint-Gaudens looked for the perfect likeness and pose for his work. Saint-Gaudens no doubt consulted numerous photographs for the work, most likely taking the photographs of Mathew Brady with him to his summer home in New Hampshire along with his personal recollections and memories of Lincoln. Saint-Gaudens may have found the January 8, 1864 photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken by Brady useful, as it features the President standing with his left arm behind his back, a gesture added into Standing Lincoln.7 As for the “Lincoln shaped men” of New England, Saint-Gaudens found his “Lincoln” in Langdon Morse, who resided in Vermont. The sculptor carefully studied the physique of Abraham Lincoln, searching for a model who closely corresponded with that of the President, using Morse as his model during the duration of the creation of Standing Lincoln.8 The sculptor had his model dress in a suit accurately tailored to replicate Lincoln’s, being so meticulous as to have Morse walk around the property of his Cornish home until the clothes acquired the correct wrinkles.9 Saint-Gaudens strove for perfection in all his statues, but given the coveted status of the Lincoln commission, he went to great lengths to ensure the statue was an accurate portrayal of the President.

Saint-Gaudens heavily relied on the life mask and casts of hands of Abraham Lincoln done by Leonard Wells Volk in 1860, taking several characteristics from these and using them for his work. In 1886, an aide and friend to Saint-Gaudens, Richard Watson Gilder, noticed an intriguing mask of Abraham Lincoln in New York City, taking note of the realistic portrayal of the President. When discovered to be the life mask taken by Volk, Gilder borrowed the pieces, giving them to Saint-Gaudens to use for his sculpture. Gilder recalled that Saint-Gaudens was “greatly helped by the Volk life-mask in his modeling of the head of Lincoln.”10 Saint-Gaudens incorporated Lincoln’s high forehead, large ears, deep-set eyes, and facial structures into his sculpture, adding tousled hair, bushy eyebrows, and a trimmed beard to give Lincoln a familiar look.11

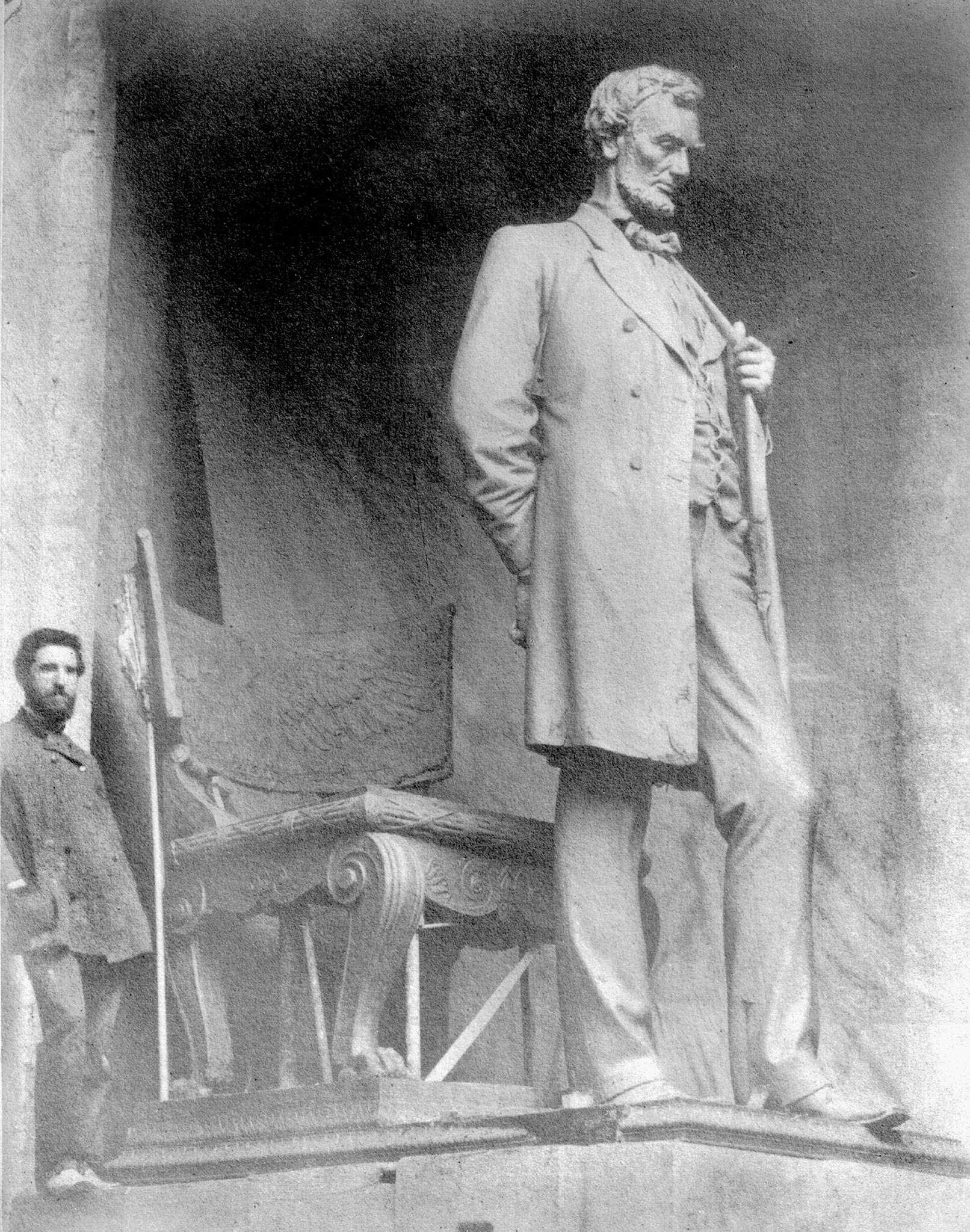

In the final model of Standing Lincoln, Saint-Gaudens’s conception of Lincoln became one as an orator and a man fraught with worry. Saint-Gaudens had created a Lincoln who was a “heroic and noble figure, deep in thought, who appears to have just risen from the chair behind him to begin and address.”12 His final conception of Lincoln was innovative for the time, a motionless President standing in front of the Chair of State. Saint-Gaudens presented Lincoln “not as a man of action, but as a man in an intensely private, introspective moment, preparing to lift his head to address his audience.” Standing Lincoln features an Abraham Lincoln whose left hand grasps the lapel of his frock coat while his right-hand rests behind his back, loosely clenched into a fist. Lincoln’s left foot projects off the granite pedestal, designed by Saint-Gaudens’s friend Stanford White, into the realm of the audience.14

Augustus Saint-Gaudens devoted nearly three years of his life to the Lincoln statue as he embodied in bronze the “dignity and nobleness of the President’s character.”15 On October 20, 1887, the bronze Abraham Lincoln was lifted into place on the granite pedestal in preparation of the dedication of the statue set to take place two days later. On October 22, over six thousand spectators and lovers of Lincoln gathered at Lincoln Park in Chicago, Illinois, to see the dedication of Saint-Gaudens’s monument.16 In attendance was the sculptor, Lincoln’s son Robert Todd Lincoln and grandson Abraham Lincoln II.17

Saint-Gaudens placed great thought and diligence into the creation of Standing Lincoln, ultimately creating the most realistic statue of Lincoln, according to many of Lincoln’s contemporaries, including Lincoln’s son Robert. Lincoln simply stands before a chair, preparing himself to speak to an audience as he had done numerous times in life. Saint-Gaudens purposefully removed many of the biographical titles given to Lincoln, most prominently the “Great Emancipator.” His statue features a lone Lincoln, draped in a “modern suit of clothes,” as he grasps the lapel of his long, unbuttoned frock coat and the other hand remains empty behind his back.18 Saint-Gaudens could have draped Lincoln in a toga or robe to romanticize the President, but instead opted to dress him in a suit to ensure that he remained a simplistic “man of the people.”19

Saint-Gaudens omitted any artificial sculptural devices in his Standing Lincoln, including items such as a scroll or parchment document, which many sculptors before him had included.20 Lincoln stands thoughtful in front of his audience, pondering what he is to say next at which he would lift his head and “tell them, out of his greater knowledge of the conditions besetting the Administration, all that he can safely publicize, and why he may not be able to grant all they ask.”21 One of the few symbols that is present in Standing Lincoln is the Chair of State that rests behind the standing figure, which reflects a strong national symbol. Saint-Gaudens intentionally oversized the Chair of State to emphasize the power of the President as well as Lincoln’s presence as President during the American Civil War. This deliberate artistic choice highlights Saint-Gaudens’s praise of Lincoln, as the sculptor no doubt recalled his memories of Lincoln.

Saint-Gaudens offered his audience one of the most realistic statues of Abraham Lincoln. It is important to note that Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Standing Lincoln pushed against the typical narrative of the life of Abraham Lincoln for the time it was created. The monument was created during an era where Lincoln’s memory was that of a martyred President, soon to become a venerated and romanticized figure and statesman. Saint-Gaudens portrays Lincoln not as a romantic figure in American history, but of a solemn statesman of the people, preparing to speak before a group of people. He stands, contemplatively thinking of his next line, prepared to address his audience.

Savannah Rose is a 2017 graduate of Gettysburg College and former student of Allen Guelzo. She received a degree in History, Civil War Era Studies, and Public History. She currently works as a Pathways National Park Service Ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park, and is working towards her Masters degree at West Virginia University.

Endnotes

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, ed. Homer Saint-Gaudens (New York: The Century Co., 1913), 41.

- Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 42.

- Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 51.

- Merrill D. Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 18.

- “Between Augustus St Gaudens and George Payson, James C. Brooks and Thomas F. Withrow as Justices: Contract,” November 11, 1884, Dartmouth College Rauner Special Collections Library.

- Saint-Gaudens, Reminiscences, 312.

- Thayer Tolles, “Abraham Lincoln: The Man (Standing Lincoln): A Bronze Statuette by Augustus Saint-Gaudens,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 48 (January 2013): 226.

- Frank E. Stevens, “The Story of a Statue,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 24 (April 1931): 21.

- Lincoln Bicentennial: 1809-2009 (Cornish, NH: Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, 2009), 9.

- Richard Watson Gilder to Homer Saint-Gaudens, March 25, 1909, in Letters of Richard Watson Gilder ed. Rosamond Gilder (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916,) 149.

- Tolles, “Abraham Lincoln: The Man (Standing Lincoln),” 226.

- Kathryn Greenthal, Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Master Sculptor (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), 126.

- Tolles, “Abraham Lincoln: The Man (Standing Lincoln),” 227.

- F. Lauriston Bullard, Lincoln in Marble and Bronze (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1952), 81.

- “Eli Bates’ Great Gift,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1887.

- “The Ceremonial,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 23, 1887.

- “The Ceremonial,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 23, 1887.

- “The Ceremonial,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 23, 1887.

- Bullard, Lincoln in Marble and Bronze, 83.

- Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 122.

- Bullard, Lincoln in Marble and Bronze, 82.