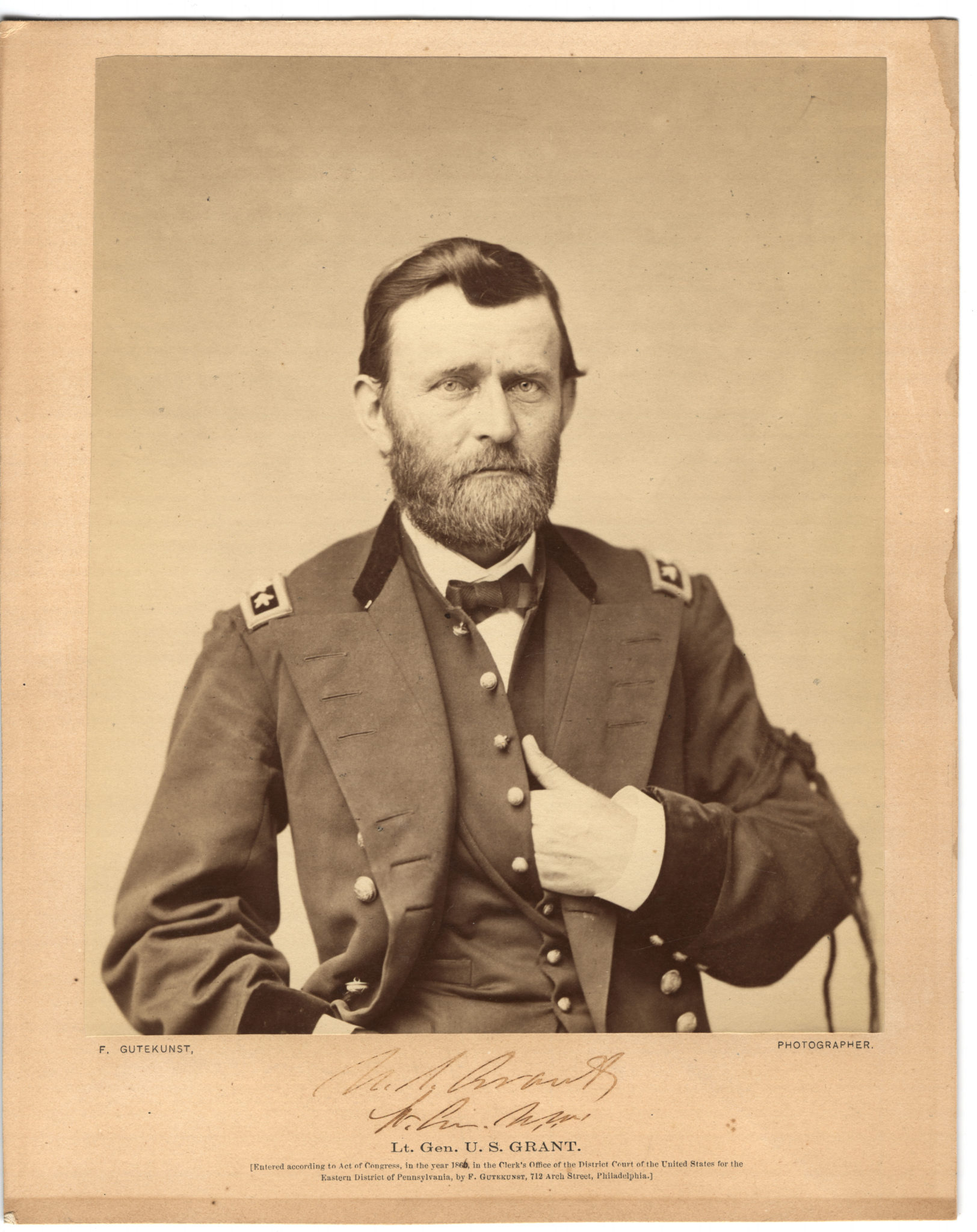

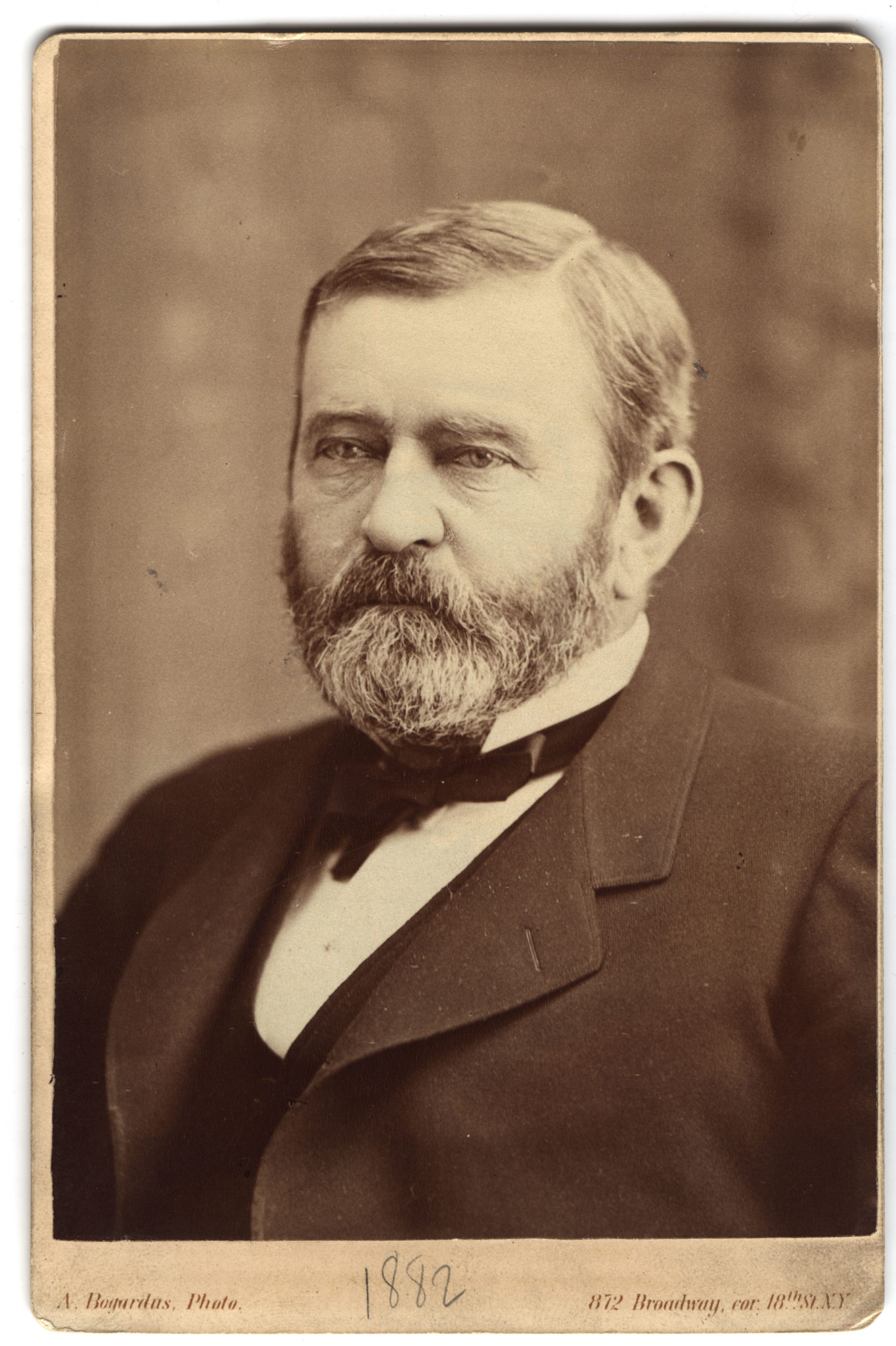

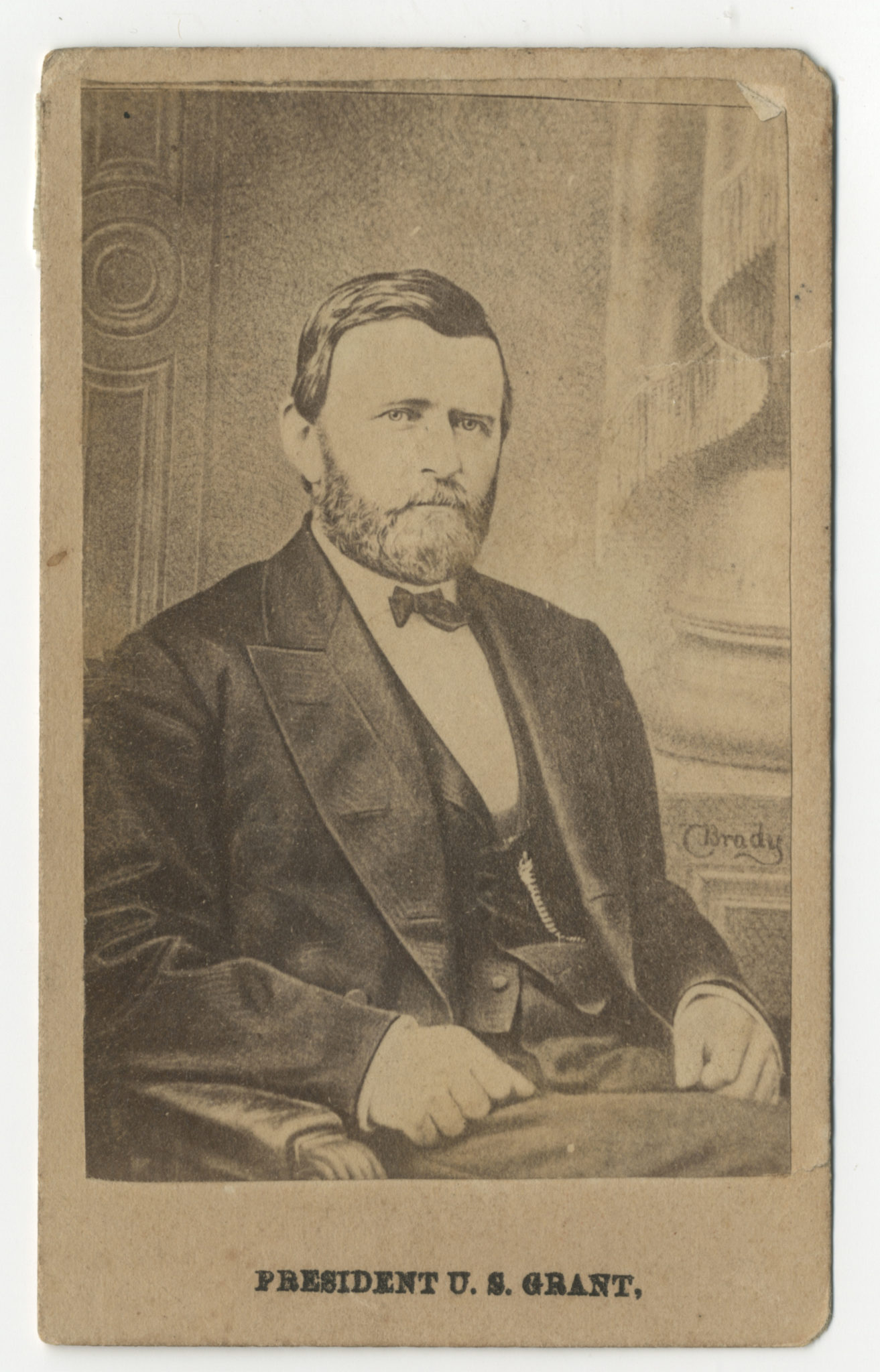

An interview with Ronald C. White, Author of American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant

Sara Gabbard: Did you find your extensive background in the study of Abraham Lincoln a help in your research on Grant, or was it a distraction?

Ron White: At one level, writing three books on Lincoln helped. I came to believe Lincoln and Grant formed a mutual admiration society. At another level, it did not help. Because Grant was an important figure in my Lincoln biography, I started out believing I knew the man. It was not long before I had to make a personal confession: I did not know Grant. Yes, I knew what he did—command the Union armies that won the Civil War—but I did not know who he was. And I was sure most Americans also did not know the man.

SG: Did you find influences in Grant’s childhood that might have contributed to his eventual successes?

RW: Some of my first readers warned me about spending too much time on the young Grant. Biographies are popular today, but many move quickly over the early life of their subject. I took my cue from Grant himself who wrote: “I read but few lives of great men because biographies do not, as a rule, tell enough about the formative period of life. What I want to know is what a man did as a boy.”

SG: What was his experience at West Point?

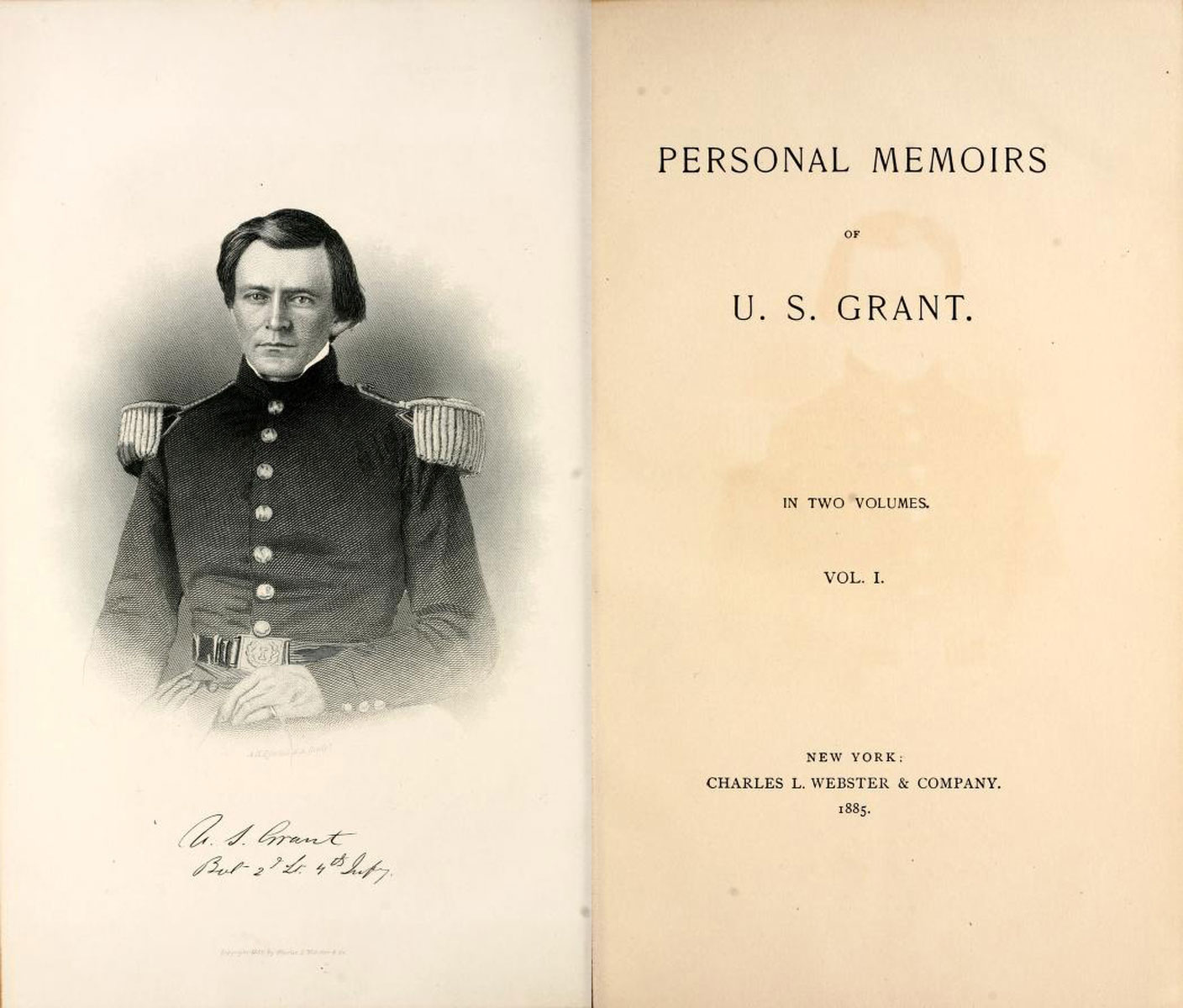

RW: In a similar fashion, previous biographies, to my mind, spent too little time with Grant at West Point. I spent one week at West Point attempting to understand his time there. Grant finished 21st out of 39 in his 1843 graduating class. This rank has contributed to the characterization that he was an intellectual light weight. In his Personal Memoirs Grant apologized: “I spent most of my time reading novels.” He tells us what novels he read. So, I spent considerable time reading what Grant read. Novels in Grant’s day were often quite didactic: “Young reader, you should…” I came to believe that the authors of these novels became tutors for the shy boy from Ohio who was not much interested in some of the traditional science and engineering classes at West Point.

SG: How would you describe, for better or for worse, the time he spent in California?

RW: Posted to Oregon, and then California, forced to leave Julia behind, he fell into loneliness and depression and drinking. On the day he was raised to the rank of Captain, the Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, received Grant’s letter of resignation. He wanted to return to Julia and to his two sons, one of whom he had never seen.

SG: Please give a description and provenance for the Grant Collection at Mississippi State.

RW: I had the benefit of using the complete Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, only completed in 2017. But these 32 volumes comprise only 20% of what is at the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library. I made five trips to the library and benefited from the counsel and guidance of Executive Director John Marszalek and his marvelous staff.

SG: You and I once shared a mutual sadness that the option of using only electronic resources for historical research is not the same as actually “holding the papers in one’s hand.” Please speak to this issue.

RW: I do worry about the new reality of historians working mainly online from their offices at a university instead of traveling to archives and to where their subjects lived, worked, and fought.

SG: I have always been fascinated by the eventual friendship between Grant and Mark Twain. Please comment.

RW: Twain called himself “Grant intoxicated.” Grant did not intend to write his memoirs. He believed memoirs—including William Tecumseh Sherman’s Memoirs—were self-serving and used to settle scores. Only when he was diagnosed with cancer, and wished to provide for Julia after his death, did he agree to do so. He almost signed a contract with the Century Magazine when Twain called on Grant and persuaded him to let Twain’s new company publish them. Twain saw Grant’s promise as a writer when others did not. Twain did not write Grant’s memoirs as some have charged. Twain published the memoirs after Grant’s death and they earned $450,000 for Julia.

SG: Please describe Grant’s post-presidential-financial-woes.

RW: There were no presidential pensions in Grant’s day. Grant’s second son, Buck, became a partner with Ferdinand War, a young Wall Street whiz. The new firm appeared to be doing well and Grant put all his money with Grant and Ward. Ward turned out to be a crook involved in a Ponzi scheme. Grant lost all his money on one terrible day in 1884. Ward went to jail.

SG: What was Grant’s attitude about the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments?

RW: Although Grant’s father, Jesse, was strongly anti-slavery, Ulysses did not involve himself in this issue until his empathy was aroused by African-Americans coming into Union lines when Grant campaigned in the deep South. As a Civil War general Grant was deferential to civilian authority and non-political. His political education began after the end of the war when he lived in Washington and served both as General of the Army, and briefly as Secretary of War. He strongly supported these three Reconstruction amendments.

SG: In your research for this book, what new material most surprised you?

RW: I came to believe that Grant was an introvert—a term not in use in his day—who usually did not reveal his feelings in letters or speeches. Except to Julia. She kept all his letters. These letters became a goldmine in my attempt to understand the inner character of the man.

SG: As a military man, what were Grant’s greatest strengths?

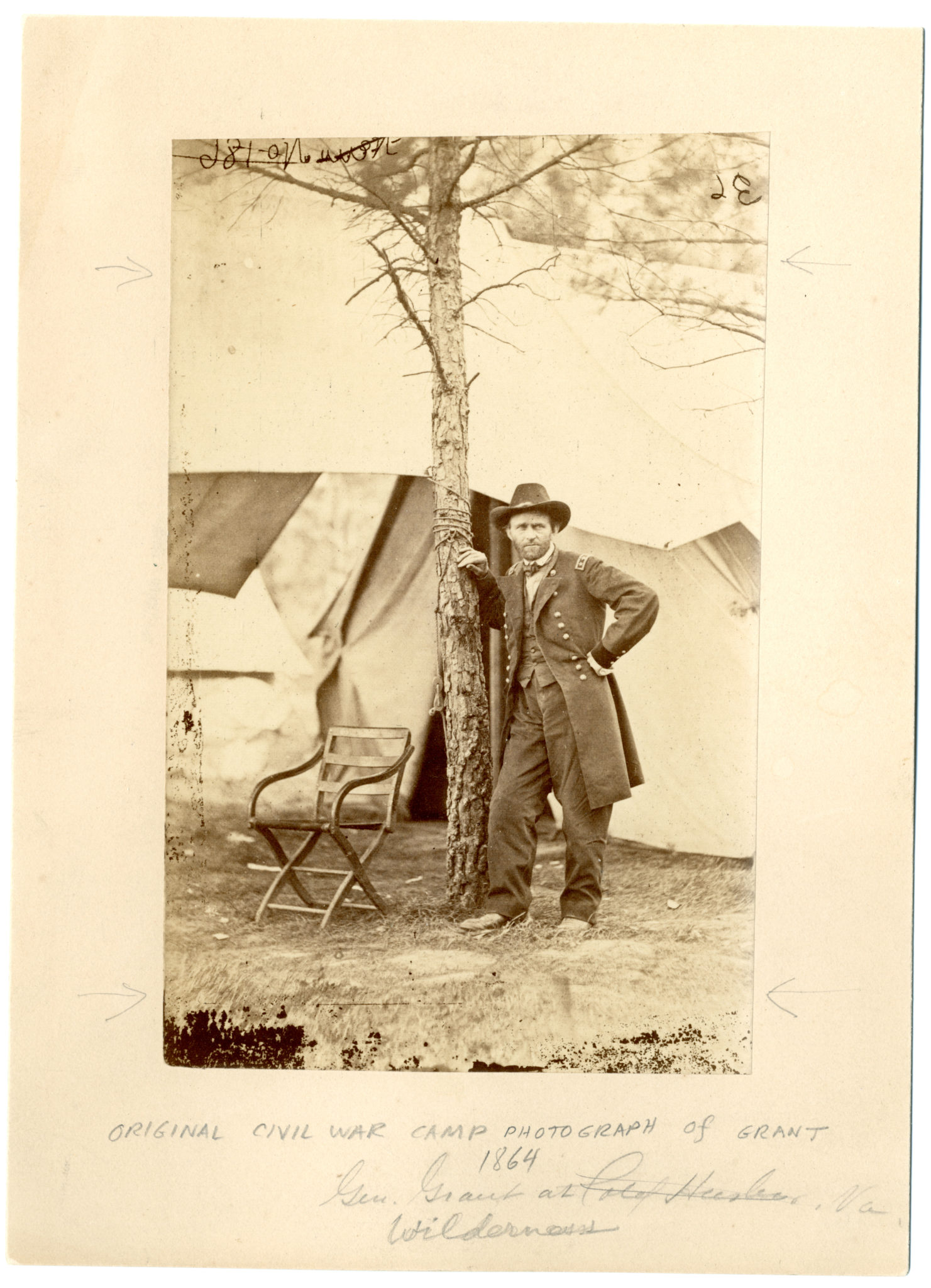

RW: Before the Civil War, the largest American army, just 14,000 men, had been commanded by Winfield Scott in the Mexican-American War. Grant had a least two great strengths. First, he had the ability to command large armies. After Lincoln gave Grant command of all the Union armies in 1864, Ulysses coordinated five armies. Second, Grant’s determination, what Lincoln called Grant’s “pertinacity.” Usually Civil War armies would fight for several days and then pause to refit. Grant, with a larger army, determined to keep up his unrelenting attack on Robert E. Lee. Because of this book I have entered a friendship with General David Petraeus. We have done three events together. General Petraeus tells audiences that Grant is America’s greatest general. He read Grant in preparing to read the “Surge” in Iraq. He commends Grant’s determination.

SG: What kind of reputation did he have with his troops? With his officers?

RW: Grant was a soldier’s general. He generally wore a private’s uniform. In the Mexican-American War he watched closely the two leading American generals: Winfield Scott, old “fuss and feathers,” and Zachary Taylor. He much preferred Taylor for his approachability to the common soldier. Taylor became his model. He worked well with officers because he listened and never micro-managed. In the battle for Chattanooga Grant had responsibility for the whole of East Tennessee. Ambrose Burnside, who had suffered a humiliating defeat at Fredericksburg, and was now mocked by newspapers as “Burnside the Incapable,” was tasked with defending Knoxville. I was impressed with how Grant approached Burnside without prejudgment which heartened both Burnside and his staff.

SG: What were his comments about Robert E. Lee? About the Treaty of Appomattox?

RW: Grant is respectful towards Lee, but his Memoirs offers greater praise for Confederate General “Old Joe” Johnston. The character of Grant is revealed at Appomattox. First, he forbad his soldiers from doing anything to demean the defeated Confederate soldiers. “The war is over: the rebels are our countrymen again.” Second, he offered a magnanimous peace treaty which allowed the defeated soldiers to keep their horses that they might take them to their homes for spring planting.

SG: Probably not a fair question, but please give a brief description of Grant’s presidency.

RW: I approached Grant’s presidency with no prejudgments, but aware of the popular characterization: Grant was a great general and a poor president. I came to believe the scandals in Grant’s second term had obscured all that Grant accomplished in both terms. Here let me suggest just three of his accomplishments. He was first American president to attempt to deal with the immorality of our policies toward the American Indian. Second, with a high volume of anti-British feeling in the air, he put in place a treaty with Great Britain negotiated through international arbitration that became the foundation of our relationship with our closest international partner. Third, and most importantly, just as his Republican party stepped back, he stepped forward to use the power of the federal government to protect the rights of African-Americans, especially the right to vote, against the terrorist attacks of the Ku Klux Klan and the other white leagues.

SG: From what I have read, it appears that Julia Grant was an exceptional woman. Please comment.

RW: I quickly came to believe that Julia had been minimalized and marginalized in the Grant story. With more education than was typically offered to girls in her time, she entered into a remarkable marriage and partnership. If Grant was an introvert, she was an extrovert who, after the scars left by Mary Lincoln’s enemies list, welcomed people to a hospitable White House.

SG: Please describe your position at the Huntington Library. What is your next scholarly project?

RW: I am a Fellow at the Huntington Library. I am privileged to work in this remarkable library with its huge Civil War collection. My next project is a biography of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Rediscovered through the novel Killer Angels, the Ken Burns Civil War Documentary, and the movie Gettysburg, Chamberlain is well known to Civil War buffs and unknown in the public. If he has been returned to heroic stature, Little Round Top now being the most visited place at Gettysburg, the temptation has been to miss the ambiguities and contradictions in his remarkable life.

Ronald C. White is a Fellow at the Huntington Library and a Senior Fellow of the Trinity Forum in Washington, D.C.