An Interview with Lincoln Artist, Wendy Allen

Sara Gabbard: What first attracted you to Abraham Lincoln as a subject for your art?

Wendy Allen: The first question people always ask me is, “Why do you paint Lincoln?” It’s never easy to explain a passion. Simply put, I am painting the exact location of America’s soul.

One of my favorite authors is the late Dr. Richard Selzer, a retired surgeon who taught and practiced at Yale-New Haven Hospital. He was a marvelous writer and poet. In his series of essays, The Exact Location of the Soul, he concluded that the human soul resides in its wounds—and that the strength and character of that soul are shaped by the wounds it works to overcome.

I believe that America’s soul, defined by the wounds of the Civil War, was born at the precise moment Lincoln concluded his address at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. The strength and character of his words, shaped by the most horrific battle that has ever taken place on this continent, ennobled the nation’s sacrifices, made true our sacred charters of freedom—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—and forever changed the course of American and world history.

“Delicate durability” is another phrase Dr. Richard Selzer used to describe the human body in his book Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery. I read it many years ago, but the words still reverberate.

For many years my mother suffered from terminal cancer. She died while I was in college. It was sad, of course, but also oppressive to witness her decline with all of her anger and depression. Her final years, and then her painful death, transformed my life forever. I had always known that I was delicate. But I also found I was durable.

During this time, my college biology professor, Dr. Michael Autuori, challenged the class to consider “What most distinguishes humans from other animals?” We offered up the common observations, such as having a sense of morality. But—like God himself—he dismissed them all. “Humans,” he said, “have a sense of history.” I loved that answer. It was then that I decided to learn as much as I could.

Simply put, I am painting the exact location of America’s soul.

In 1979, I moved from Connecticut to Northern California. It was a foreign land, and I felt liberated. My earliest jobs exposed me to art. As my interest grew, I began visiting all the art museums in San Francisco and Oakland. I flew back to New York in 1980 just to see the monumental Picasso exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. It was at about that time that I decided to become an artist. I had no formal training, but I wanted to paint.

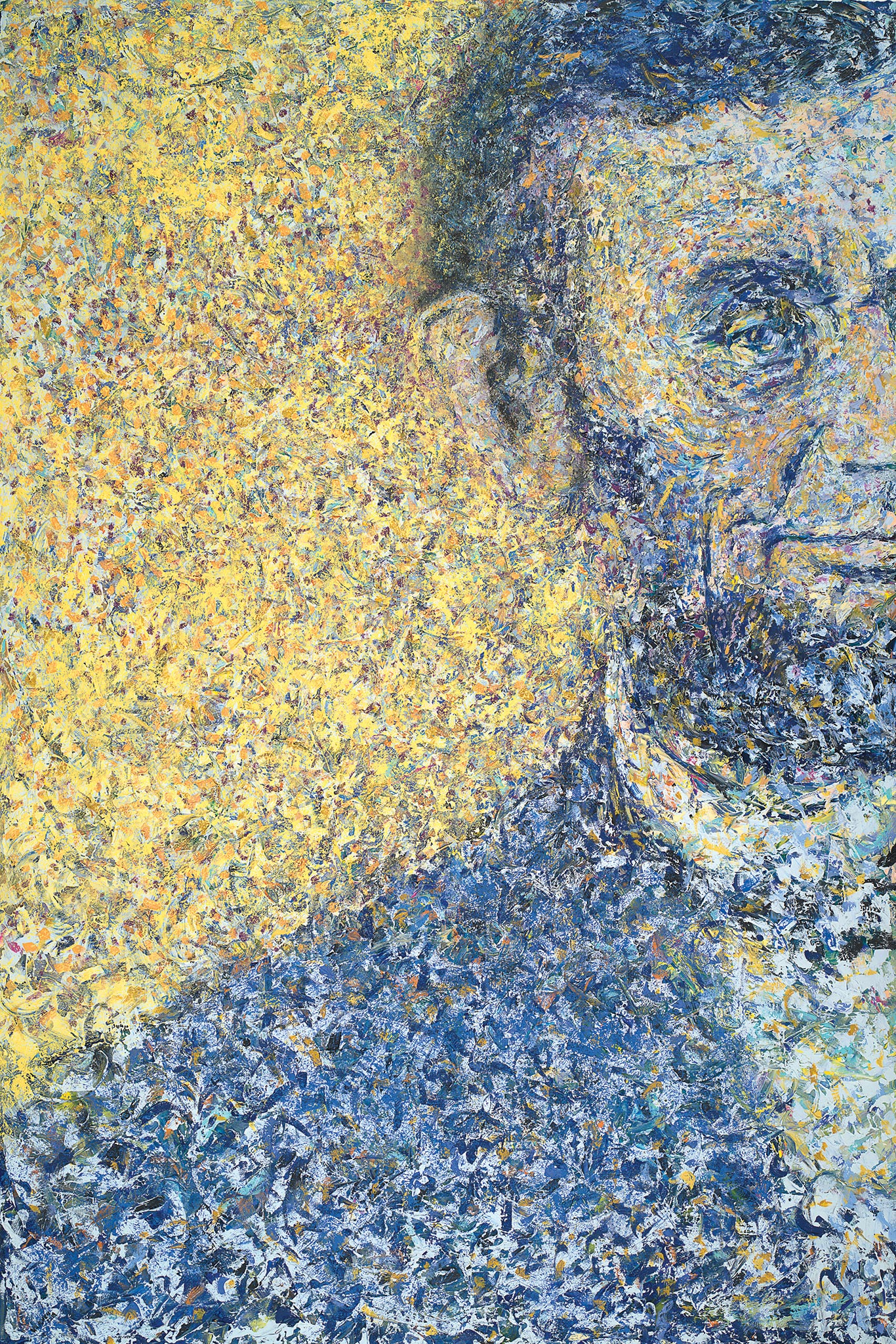

My first paintings, naturally, were amateurish. But what bothered me the most was that I could not find a subject that interested me. Everything I painted felt unimportant. I read voraciously about the masters, learning their secrets and experimenting with different techniques, straining to ignite the canvas with originality. The problem was that I was trying to paint like the artists who inspired me.

Elaine de Kooning once wrote, “If [the artist] did not desire to change all art, he would never get past his love for the artists who first inspired him and be able to paint his own pictures.” That meant, to be original, I had to rebel against the great modern artists I loved. But the more I studied and learned, the more I grew frustrated. I still had not found a subject that inspired me. I certainly did not find it in the art I had grown to love.

Finally, it hit me. Modern art contained no history, the very subject I had grown to value most. Artists had turned their backs on history! How, I wondered, could they ignore the very thing that defines us as human?

My life as an artist was defined. It was time for me to rebel.

In the summer of 1983, I attended the very first conference of the Civil War Institute, founded at Gettysburg College by my now dear friend Dr. Gabor Boritt, one of the world’s great Lincoln scholars. That experience changed the course of my life. I returned to California inspired and eager to paint.

I was too poor to afford an easel, so I placed a blank canvas on the windowsill in the tiny kitchen of my small apartment in Mountain View. The moment I started painting, I became completely absorbed. I worked all night and into the morning.

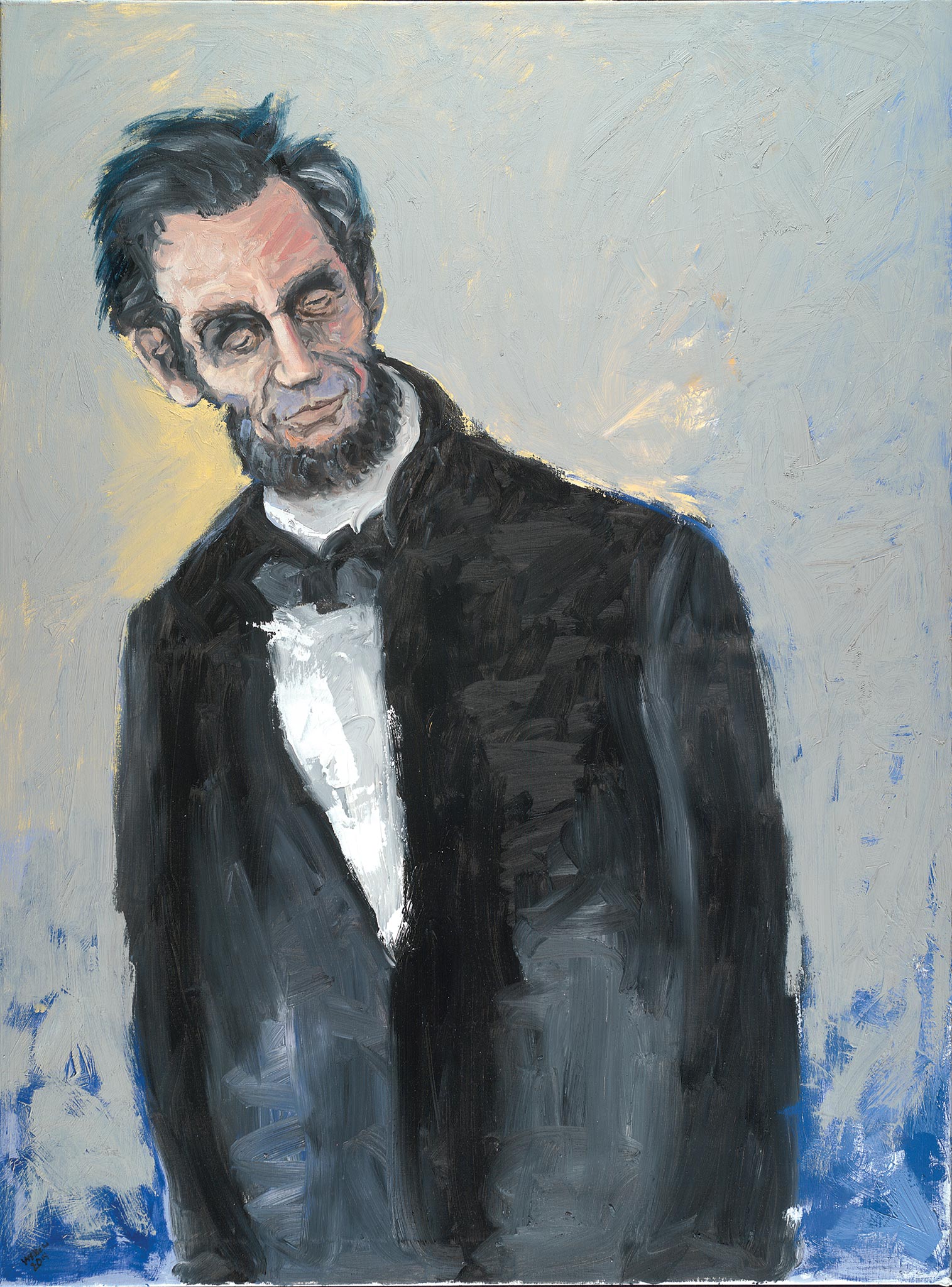

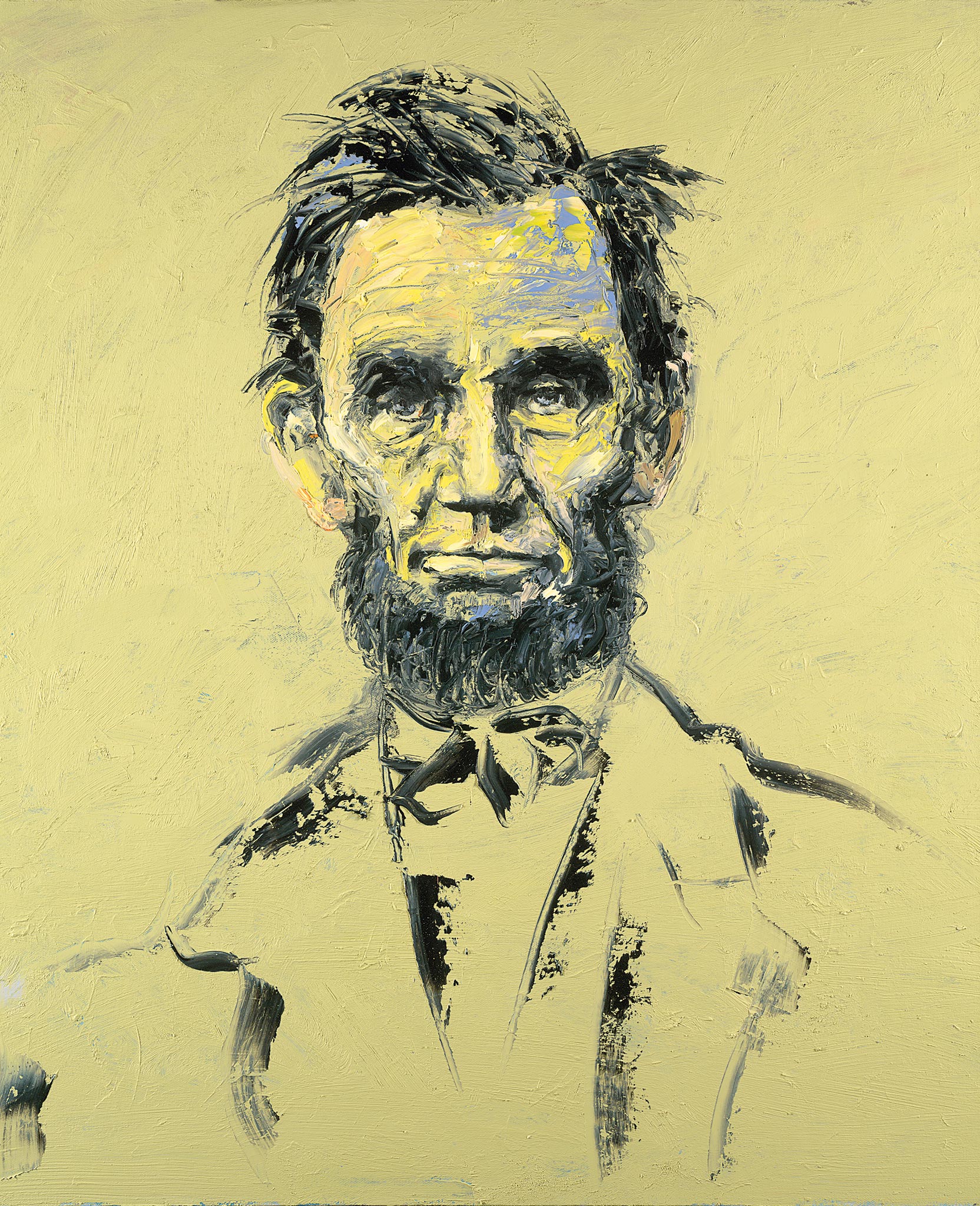

Completing that painting was an extraordinary event in my life. For the first time, I had created something that had a life of its own. It was oil and spray paint and magic and my future. Finally, my heart and ambition had translated onto canvas. I had gone into Merlin’s cave and emerged with the secret of my universe. I had painted my first portrait of Abraham Lincoln.

Looking back now, I wonder why Lincoln, the ultimate subject of my art, had eluded me for so long. I had carried him with me since childhood. I had loved him long before I understood the power of his achievements. To me, he represented the best of humankind. I had found my passion. And, through my art, the world would take a new look at Abraham Lincoln—the very best that history has to offer.

SG: What aspect of Lincoln’s image do you find easiest to capture? The most difficult?

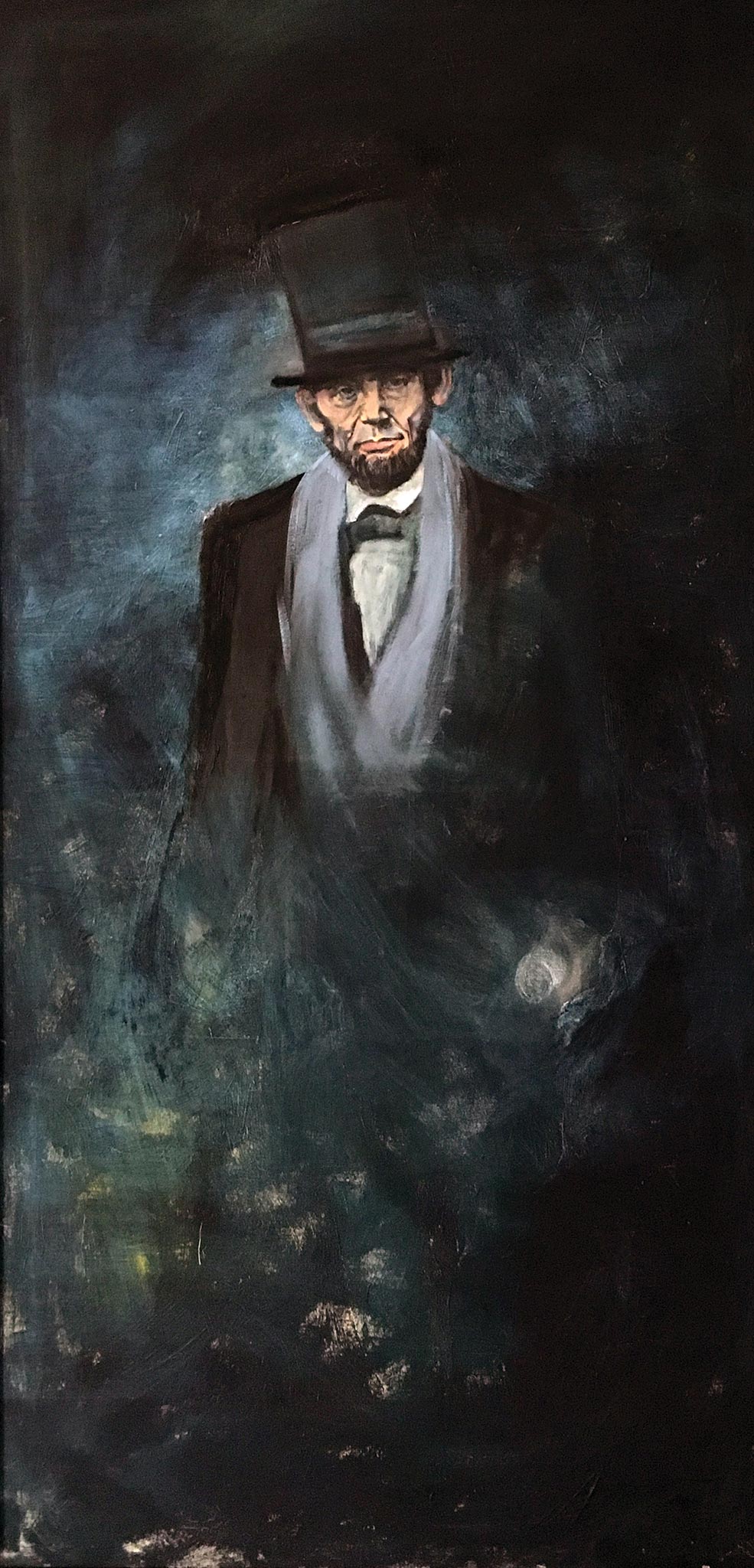

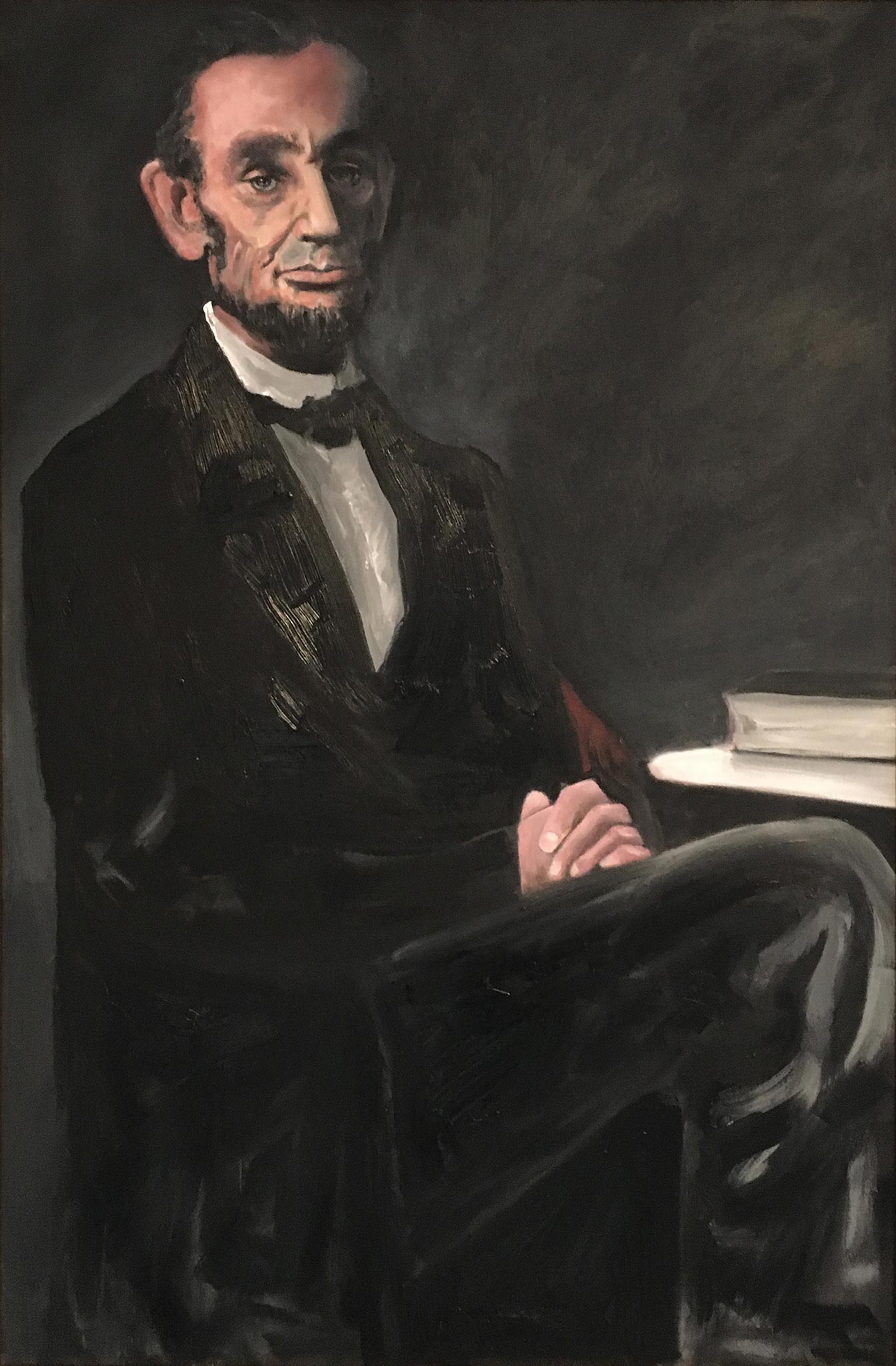

WA: Lincoln had a beautiful face. I love the daguerreotypes of him, especially the impeccably reproduced prints that show every fractaled flaw. The old portraits of Lincoln—the ones we admire today—are modest and rarely glamorized. Even in his most authoritative poses, he wears only a long black coat, a simple white shirt, and a twisted, uneven tie. On a good day, he might have combed his hair.

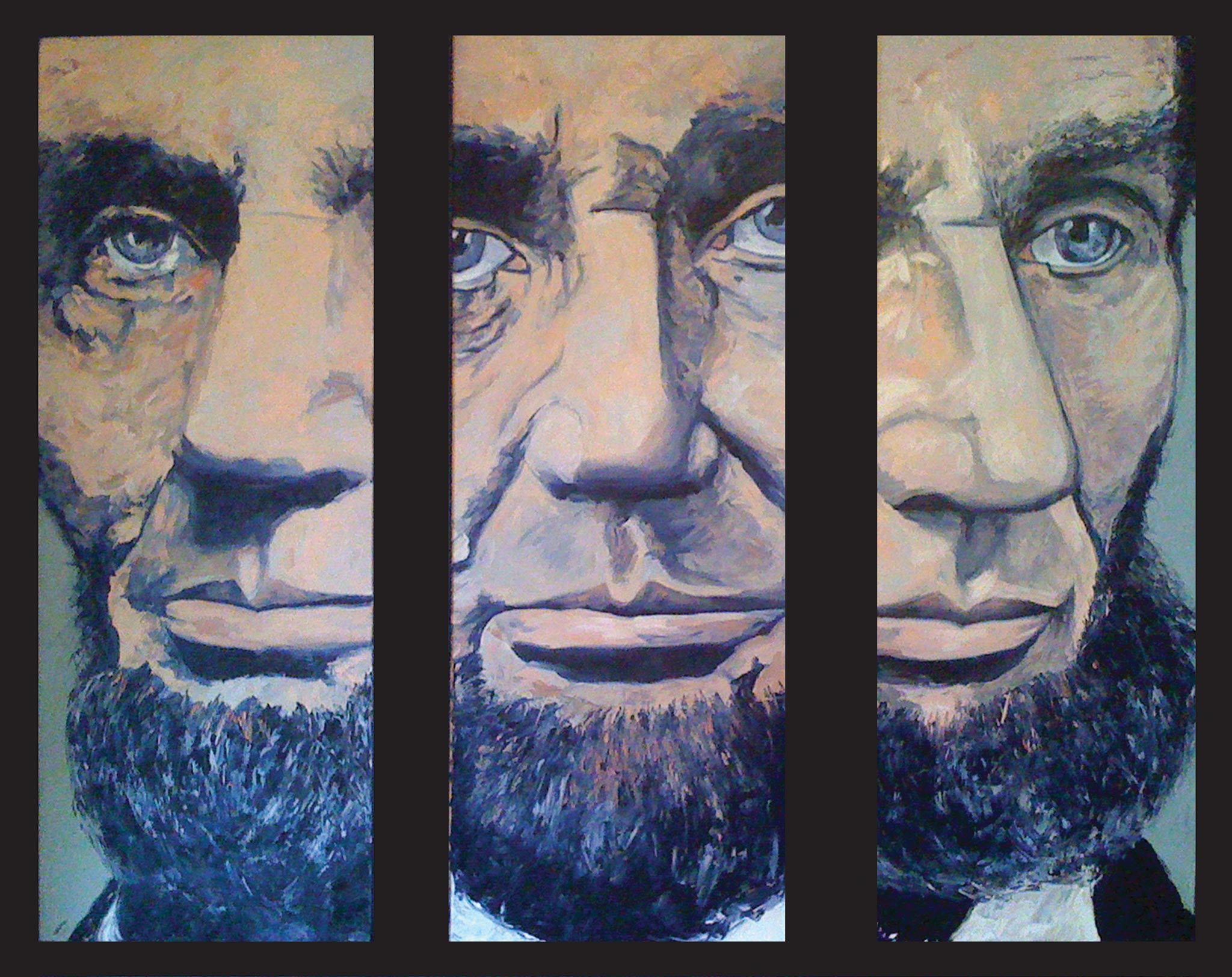

Signature shadows define him. The length of the shadow under his nose betrays its substantial size. The dark sockets of his eyes sink beneath strong brows. Lines are carved into his forehead. Unusually high cheekbones cast downward slashes that accentuate his sunken face. The creases between his eyebrows are so deep, so permanent, one would swear he had been born with them. His mouth is the most difficult to capture. There is barely an upper lip, except for the royal ‘M’ shape in the center. And his crazy bottom lip dips and sways, as if its designer did not have a chance to finish it.

SG: What led to your decision to move your studio to Gettysburg?

WA: I began visiting Gettysburg while I was in college. My sister, Caroline Allen, was a student at Gettysburg College. I visited her often to enjoy her company and as an escape from increasingly difficult times at home; my mother was dying of cancer.

I fell in love with Gettysburg and remained a loyal visitor. By the mid-1980s, I began painting and selling paintings part-time through a gallery owned and operated by Lois Starkey. She gave me the break of a lifetime deciding to sell my work at her downtown Gettysburg gallery. During that time, I made many good friends in Gettysburg. In 2008, I quit my full-time position as a creative director for a children’s publisher to open a studio and gallery in Gettysburg. I also had and continue to have the full support of my wife, Elaine. Her sister, Susan Florence Henderson, the inventor of the Bobby baby pillow was/is a generous patron and business supporter. My older sister, Amy Woodis, has now relocated to the area and is a tremendous supporter of my work and process.

There isn’t a day that passes that I don’t look out my window at Baltimore Street and think about Lincoln passing by this building on his way to deliver the Gettysburg Address. I always find inspiration in this special place.

SG: How do you begin a new piece of work? Do you use preliminary sketches?

WA: Each piece begins differently. Most paintings are impromptu and quickly sketched directly onto the canvas. And there are other paintings where I’ll develop a series of pencil sketches. I usually do these sketches when I am concerned about negative space and effective cropping. The end goal is to have the painting appear fresh. Overthinking a painting can wreck that freshness.

SG: Do current events ever lead to a new portrayal of Lincoln?

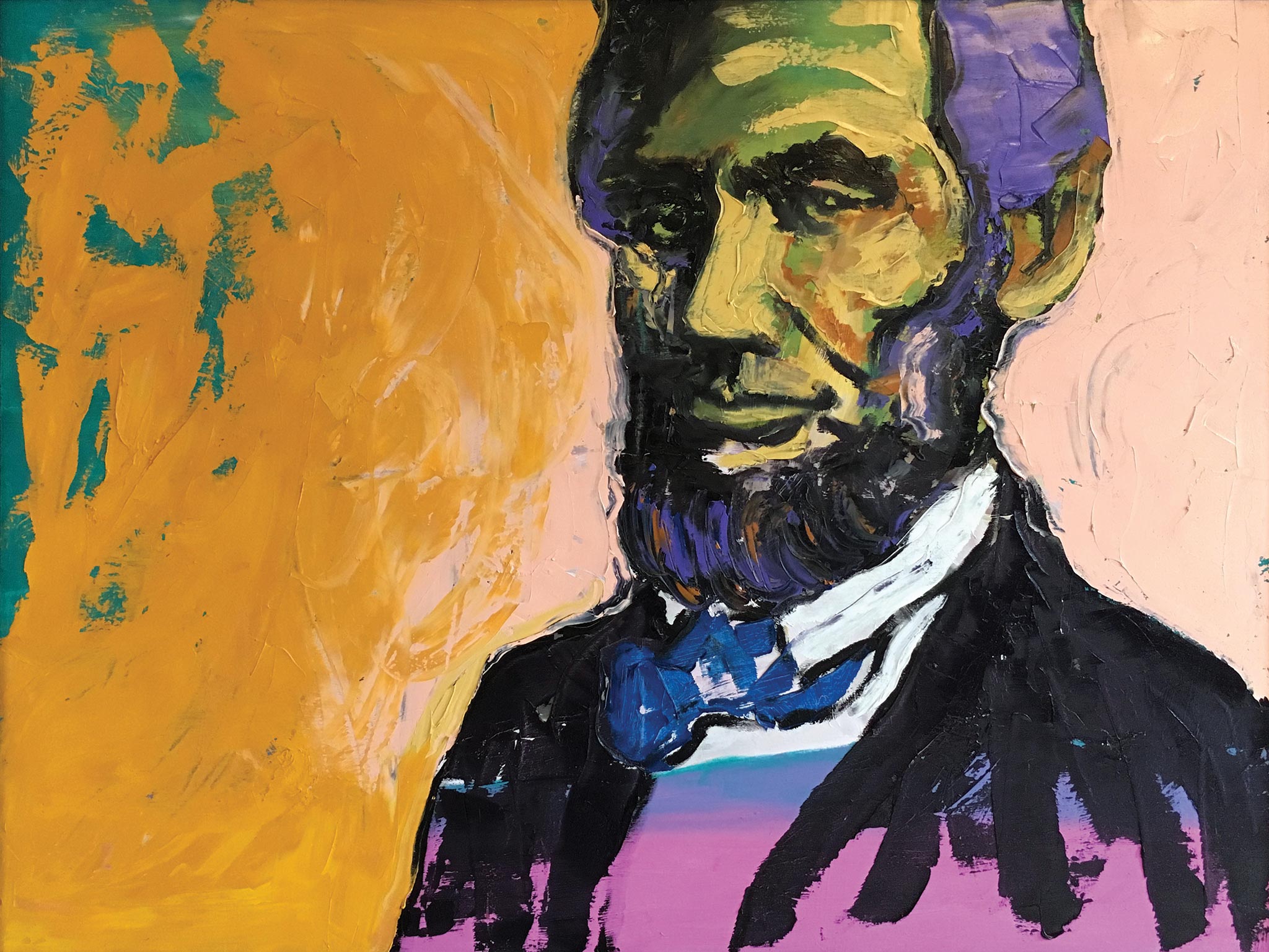

WA: This is a great question. Every Lincoln painting I complete is directly coming from a place that includes my current status in the events of the day. I don’t consider myself an “illustrator” of Lincoln or a portrait painter. I am a post-modern artist of an incredible subject.

“Prejudices, it is well known, are most difficult to eradicate from the heart whose soil has never been loosened or fertilized by education: they grow there, firm as weeds among stones,” Charlotte Brontë wrote in Jane Eyre.

America has a hard time admitting and dealing with its prejudices. But I remain an optimist. I believe in the American Dream. And I thank our Founders, who—as Lincoln famously wrote in his Gettysburg Address—”brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

There has been much discussion lately about the Founders and slavery. It’s a shockingly horrid chapter in our history, and we all hate thinking about it. It’s extremely difficult trying to make sense of the fact that the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence owned human beings. The nation had to wait almost a hundred more years for Lincoln to eradicate that horror.

America is a great democratic experiment, and for me, this great experiment based on new ideas, has been an expanding one. This idea, this proposition, is not so much the American Dream but rather the American Promise—the implicit promise that all men are not just created equal but will be given an equal chance.

True story—Not long ago, a good friend of mine told me she had been talking to a business acquaintance when the name of a female law enforcement officer came up. My friend started praising the woman, saying what a great officer she is and how dedicated she is to her work. Then the business acquaintance chimed in with the snide remark that she had heard the officer was a lesbian—so she was really only “half” a woman. Of course, when I heard the story, I gasped with a most uncomfortable response. This officer was only half a woman?! I was shocked, but pretended to laugh it off.

Then my friend said to me, “you must be used to that kind of comment.” But NO!!! I will never NEVER get used to that sort of comment. NO NO NO! To so casually diminish someone and reduce her to a fraction of who she really is, is eerily similar to the way people used to count slaves as three-fifths of a person.

The 60s and 70s were an interesting time for me growing up as a young gay girl. The Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Rights Movement—these were thrilling and dangerous times. But in addition to the general upheavals going on in the outside world, I lived with a confused feeling—deep inside, you know you are different from other people—but you don’t know how and you don’t know why.

Back in the late 60s, no one ever dared talk to anyone about being gay, so there was nothing for me to do but adapt. Like others like me, I had no choice but to keep my true feelings to myself. The problem was—I began to lie, and pretty soon my whole life became one big lie. And the older I got, the bigger the lies, which only magnified my feelings of isolation.

One of the pivotal things that separates being gay from all other minority concerns is the potential loss of love and support from one’s own family, particularly from your parents. My father and I always had a strained relationship, but when I was young, my mother was always wonderful to me. She was brilliant and I loved her and respected her opinions. But by the time I reached high school, her attitude had hardened toward me. She didn’t know anything about my private thoughts, but one day, after a typical mother-daughter squabble about nothing, she accused me of being mentally ill. She said that she had suspected it for a long time.

I had no idea how to handle that. After that, my relationship with her clearly changed, and I knew I would never be able to trust her or count on her again. She broke my heart. Sadly, it wasn’t long after that she was diagnosed with cancer and passed away.

For years I tried to work through the depression and find something or someone in my life I could really count on. When I moved to California, I came out and began to live truthfully. It was only when I stopped the lying that I became free.

It was in October 1983, 34 years ago, I painted my first Lincoln portrait.

SG: When customers walk into your studio, do they usually have something specific in mind, or do they just say, “I want something by Wendy?”

WA: Someday I hope people “want something by Wendy.” I think that’s every painter’s dream. To be honest, I’m not sure what motivates people to buy my work. I guess you’d have to ask them.

SG: What is your preferred medium? Which do you find most difficult?

WA: I love oil paint and most of my paintings are oil on canvas. I think the most difficult is watercolor.

SG: Is some of your work done on consignment? Is that easier or more difficult than creating something entirely on your own?

WA: It is very difficult for me to create something on commission. I tense up and usually choke in the execution of the piece. It never measures up to what the buyer imagines, and I hate to disappoint.

SG: Please explain the use of Lincoln in your creation of educational posters.

WA: The idea of creating educational posters, using my paintings, was suggested by a high-school teacher here in Pennsylvania. He felt that the paintings combined with Lincoln’s words would be interesting to young adults. We worked hard to get a good cross section of paintings, representing different styles and matching them with valid quotes by Lincoln. We also worked very hard at reproducing them effectively so that we could sell them at a reasonable price.

Artist Wendy Allen can be reached at: [email protected], or (717) 398 2561.