An Interview with Kate Masur on “They Knew Lincoln” by John E. Washington

An Interview with Kate Masur on “They Knew Lincoln” by John E. Washington by Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Who was John E. Washington? What brought him to your attention?

Kate Masur:

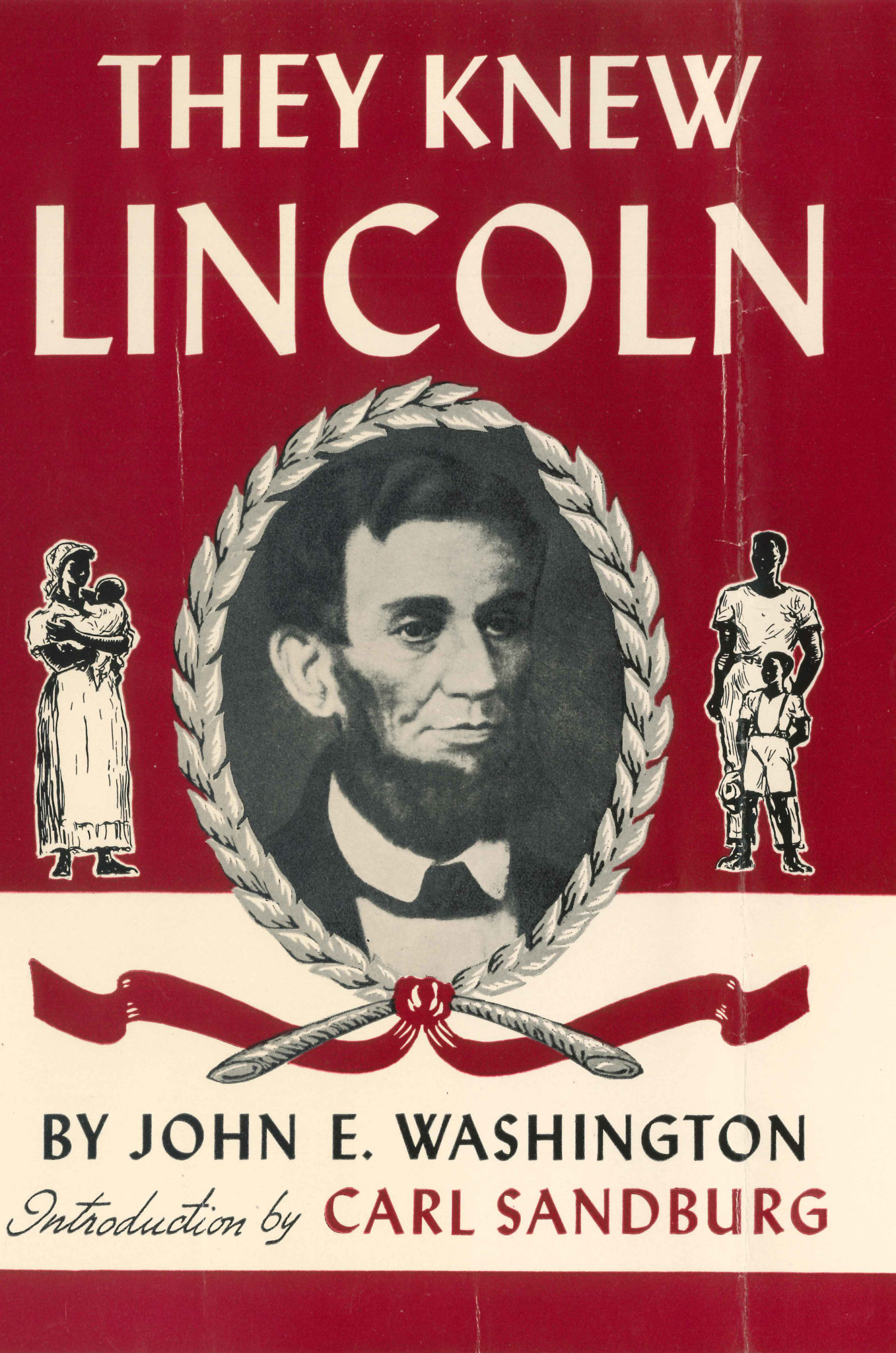

I first came across John E. Washington’s book, They Knew Lincoln, when I was a graduate student at University of Michigan in the 1990s. I found a citation to the book and wanted to have a look for myself. I found the book very intriguing, and I especially wanted to know more about the author. Who was John E. Washington, and how did he come to write and publish this book? At that time, when the internet was just getting started, it wasn’t easy to find any substantive information about Washington. I thought it was strange that he was so obscure. My primary focus at that point was writing my dissertation, but I kept thinking about Washington and his book.

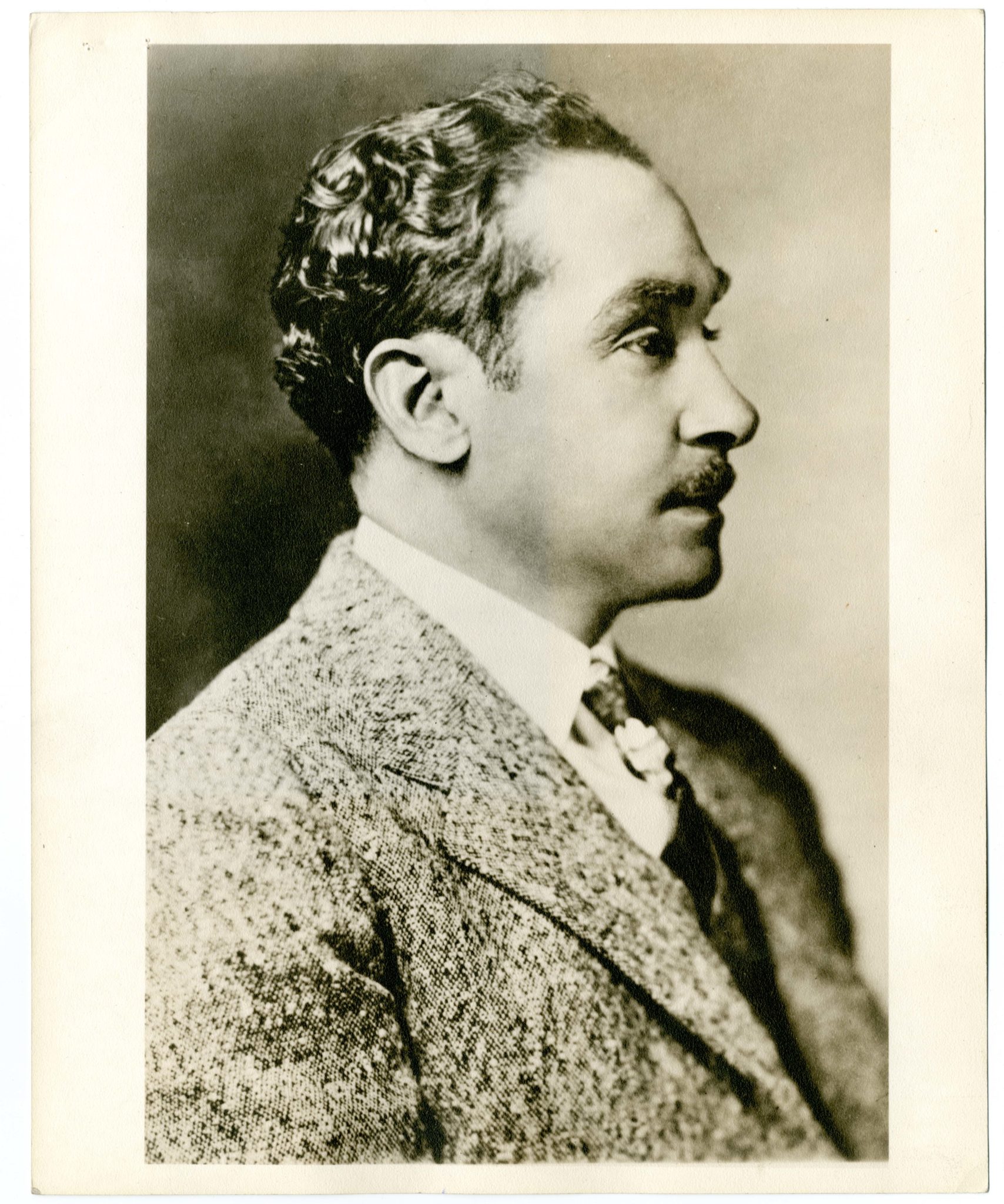

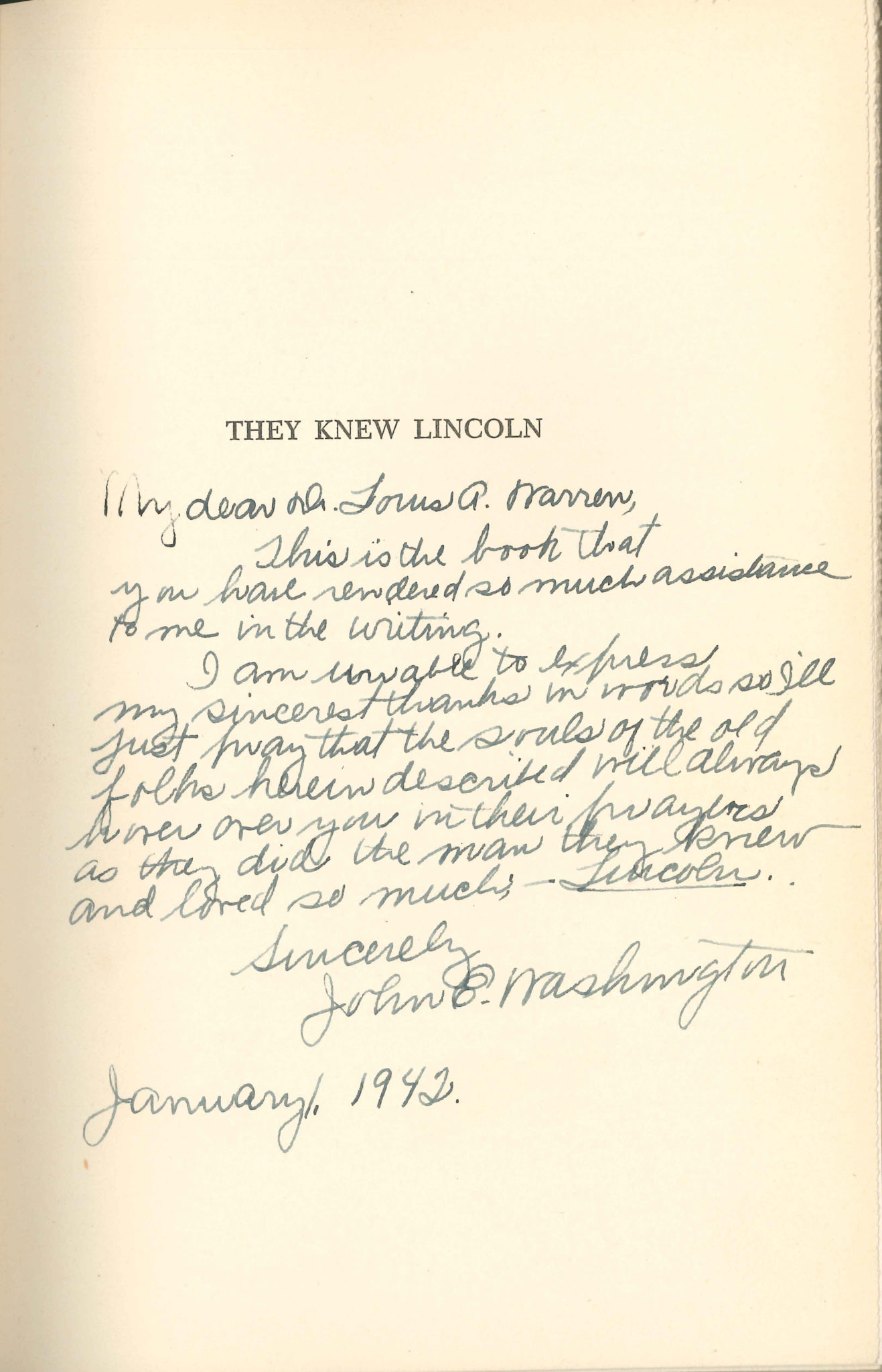

Eventually I learned quite a bit about John Washington and the origins of They Knew Lincoln. In the new edition of the book I provide a narrative of his life and work, but here are the basics: Washington was a man of many talents. The son and grandson of slaves, he was born in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1880. His parents passed away when he was young, and he was raised by his grandmother, Caroline Washington, who ran a boarding house near Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He earned three degrees at Howard University – in teaching, dentistry, and liberal arts – and taught commercial art for decades at Cardozo High School, a business high school for black students in D.C.’s segregated public school system.

Washington became interested in Lincoln and the Civil War Era when he was young. He grew up listening as his grandmother’s friends told stories of those days – of escaping from slavery, of working in the Lincolns’ White House, or of hearing the ghosts that haunted Ford’s Theatre. Washington’s motivation to write publicly about those people and their era began in 1935, when the Associated Press ran a story asserting that Elizabeth Keckly was not the author of her 1868 book, Behind the Scenes, and that in fact Keckly had never existed. Like many other African Americans in Washington, D.C, John Washington knew very well that Keckly had indeed existed and had been closely associated with the Lincolns. His effort to vindicate Keckly eventually led him to write They Knew Lincoln.

SG: Can you briefly describe the status of African Americans living in Washington, D.C., during Lincoln’s presidency?

KM: African Americans’ status in Washington, D.C., was tremendously dynamic during Lincoln’s presidency. Perhaps one way of imagining the big picture is to think about two groups: the African Americans who lived in the District of Columbia in 1861, and the thousands who migrated there during the war. Slavery was legal in the District of Columbia until April 1862, when Congress passed a law requiring that all slaves be freed (and providing compensation to slaveowners). The end of slavery in the nation’s capital was momentous. Abolitionists had been demanding it for decades. Yet the city already had a large free black population. In fact, almost 80 percent of the African Americans who lived in the District of Columbia when the war began were already free. In this sense, the capital was similar to Baltimore and other parts of Maryland, where free black people significantly outnumbered the enslaved.

The antebellum black community of Washington had managed to flourish under difficult circumstances. Its members built churches and developed schools, and by the time Lincoln became president, Washington was home to some very accomplished leaders and organizations, including people like John F. Cook, the pastor at Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, and Kate Brown, who worked in the U.S. Capitol building. Many members of the antebellum black elite had strong ties to the white elite. As in other slaveholding jurisdictions, however, the city’s laws and power structures were designed to secure slavery and racial subordination. Local laws required free African Americans (but not whites) to register their residency and imposed special curfews and licensing requirements on them.

When Congress abolished slavery in the District of Columbia in 1862, it also repealed those racist laws and, for the first time, established a public school system for African American children. Meanwhile, the Civil War, particularly in neighboring Maryland and Virginia, created opportunities for enslaved people to escape into the capital. They came to Washington seeking safety and also employment with the U.S. Army and Navy, which had significant bases in the capital. Thousands of people migrated into the District, leading to a shortage of housing and problems with control of sanitation. Members of the existing African American community mobilized to provide food, clothing, and shelter to the new migrants, but the problem was far larger than they alone could handle. The government established several “contraband camps” that provided temporary housing. In They Knew Lincoln, John Washington explains that one of his grandmother’s friends, Aunt Mary Dines, taught school and supervised the choir in such a camp, and she described what it was like when President Lincoln stopped by.

This was a period of almost unfathomable change in Washington. In 1863, African Americans publicly celebrated July 4 with a huge parade that showcased their churches, Sabbath schools, and mutual aid societies. Such a display would never have been possible before the Civil War. Black men and women demanded equal treatment on the streetcars, attended sessions of Congress, and even sought admittance to parties at the Lincoln White House.

The black population of Washington tripled between 1860 and 1870. The mix of people who lived there at the time – those who had long been free, Civil War migrants, and numerous highly political African Americans from the free states who came to the capital in search of employment and opportunity – made Washington, D.C., an exciting and interesting place during the Lincoln administration and throughout Reconstruction. African Americans demanded equality and respect in all manner of public places, and black men were enfranchised by an act of Congress in 1867. For a short time, the District had a biracial electorate and a mayor and city council that was responsive to the will of the voters. An opposition movement quickly mobilized, however, and in 1871 Congress turned the District into a federal territory, eliminating almost all elected offices and putting power in the hands of the wealthy elite. I’ve written about all this in my book, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. (2010) and also in an article, “Color Was A Bar to the Entrance,” in the March 2017 issue of American Quarterly.

SG: Abraham Lincoln has been described as both too slow and too fast in his path to emancipation. What is your take on his journey?

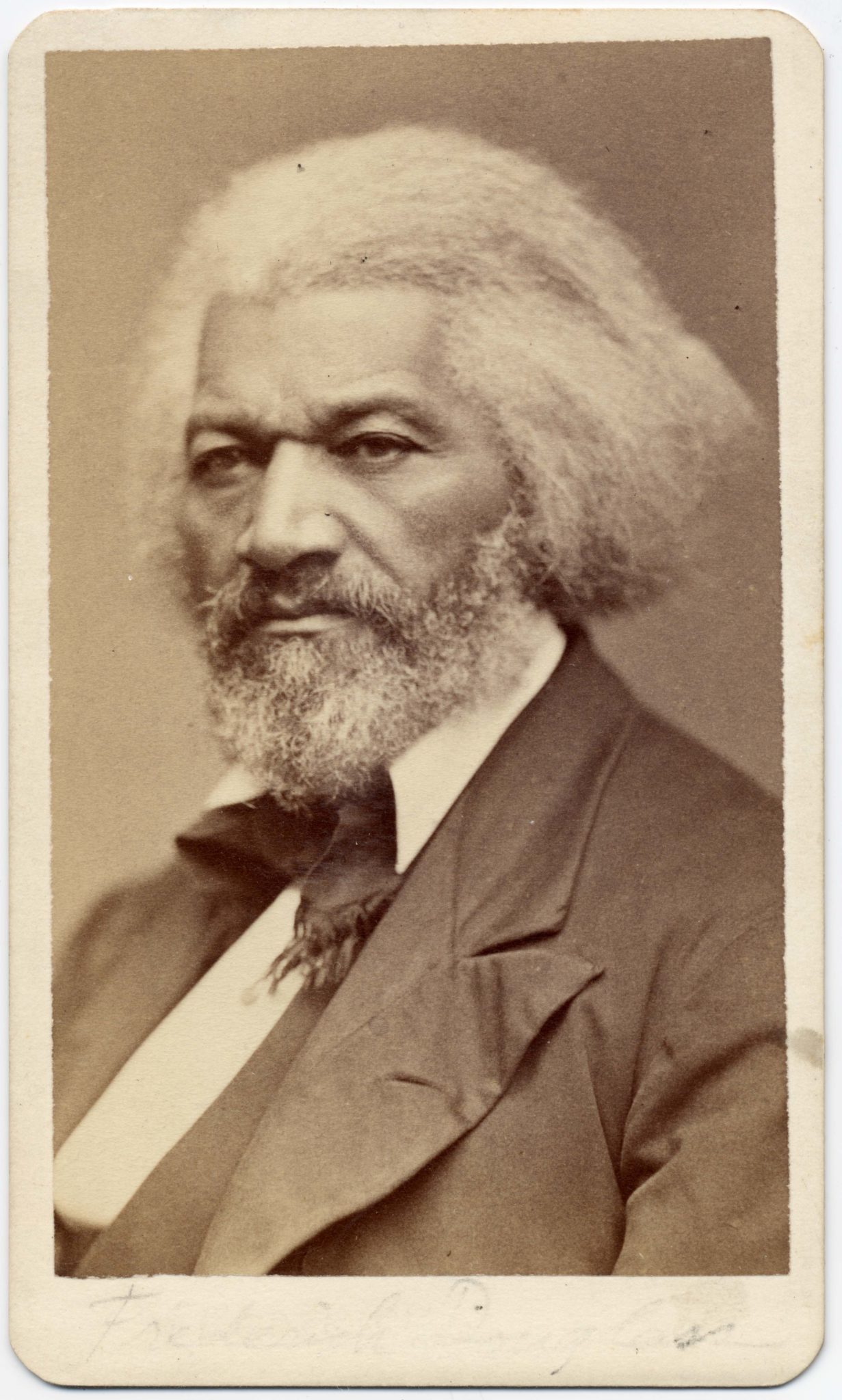

KM: I definitely don’t think he was too fast, and I can certainly understand people’s frustration that he seemed too slow. Many abolitionists believed from the beginning of the war (and even before it started) that war would bring about the end of slavery. They wanted Lincoln to hurry up and realize that – to attack slavery directly rather than, for example, insisting that U.S. military officials allow ostensibly loyal slaveowners to come into army camps looking for escaped slaves. They had no patience for Lincoln’s gradual, voluntary emancipation schemes, nor for his proposal that African Americans voluntarily leave the United States for Central America. As Frederick Douglass wrote in May 1861, “The simple way . . . to put an end to the savage and desolating war now waged by the slaveholders, is to strike down slavery itself, the primal cause of that war.” Douglass was frustrated that the Lincoln administration was not permitting black men to volunteer for the U.S. Army. He wrote, “Until the nation shall repent of this weakness and folly, until they shall make the cause of their country the cause of freedom, until they shall strike down slavery, the source and center of this gigantic rebellion, they don’t deserve the support of a single sable arm, nor will it succeed in crushing the cause of our present troubles.”

Douglass was prescient, but we also need to appreciate how Lincoln saw the issue. Particularly in the first year of the war, he worried that a full-bore attack on slavery would push Maryland or Kentucky out of the Union. Both states were strategically important for the U.S. – and would have been so for the Confederacy as well – and so it was important to show the governments of those states that the Lincoln administration was not, as so many of its opponents insisted, allied with the radical abolitionists and poised to somehow summarily abolish slavery. Moreover, and this may have been even more important, Lincoln believed slavery was legal in the states where it already existed and did not believe he had the authority, as president, to attempt to destroy it. He repeatedly asked Congress to pass legislation that would have allowed the government to pay the loyal border states to end slavery voluntarily, and he signed several congressional measures that increasingly boldly provided for the freedom of enslaved people who escaped to U.S. Army lines. But he was reluctant to use his power as president to act unilaterally against slavery. He was already wielding power more forcefully than any previous president, and he was wary of alienating northerners who suspected him of being a tyrant at heart.

Lincoln’s sense of the limits on the power of the presidency was a major reason it took him a while to decide to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. It was as commander in chief of the U.S. Army and Navy that Lincoln believed he could act against slavery, and his presidential proclamation applied only in places that were in insurrection against the United States. Yet once he took the momentous step of issuing the proclamation, which also called for the enlistment of black men as soldiers, he stood by it despite widespread opposition.

SG: What parts of Lincoln’s life and the Civil War most interest your students at Northwestern? Are there any subjects that they would prefer to ignore?

KM: I teach a freshman seminar called “Abraham Lincoln in History and Memory.” In that class we spend a lot of time reading Lincoln’s own writings, particularly on race and slavery, and then we look at how Americans have remembered Lincoln over the last 150 years or so. Maybe I’m projecting, but I think students are particularly interested in trying to figure out Lincoln’s views on slavery and race. Many have never considered, for example, why Lincoln – if he hated slavery – didn’t just wave his magic wand and end it when he became president. We end up talking quite a bit about the Constitution and also about how Americans imagine presidential power. Students are also interested in thinking about the many ways it was possible to both despise slavery and seriously doubt, as Lincoln did, that white and black people could coexist in the United States in conditions of freedom and equality. Lincoln was such a good writer that it’s always fun to engage directly with his own prose.

SG: Is Reconstruction a topic that is well understood or generally ignored?

KM: I’ve spent a lot of time writing, thinking, and teaching about Reconstruction. The period is generally not well understood, in part because it’s often ignored or glossed over, and in part because our collective misunderstanding of it runs deep. After the Civil War, Americans had to settle two crucial and interrelated questions: How would the nation be brought back together after a brutal war? And how would Americans contend with the abolition of slavery? The process of answering these questions is the history of Reconstruction. The period can be hard to understand, but I’ve come to believe that if we can break it down into these fundamental questions – questions that are absolutely central to American history – Reconstruction can be compelling for students and for all people who want to better understand the United States.

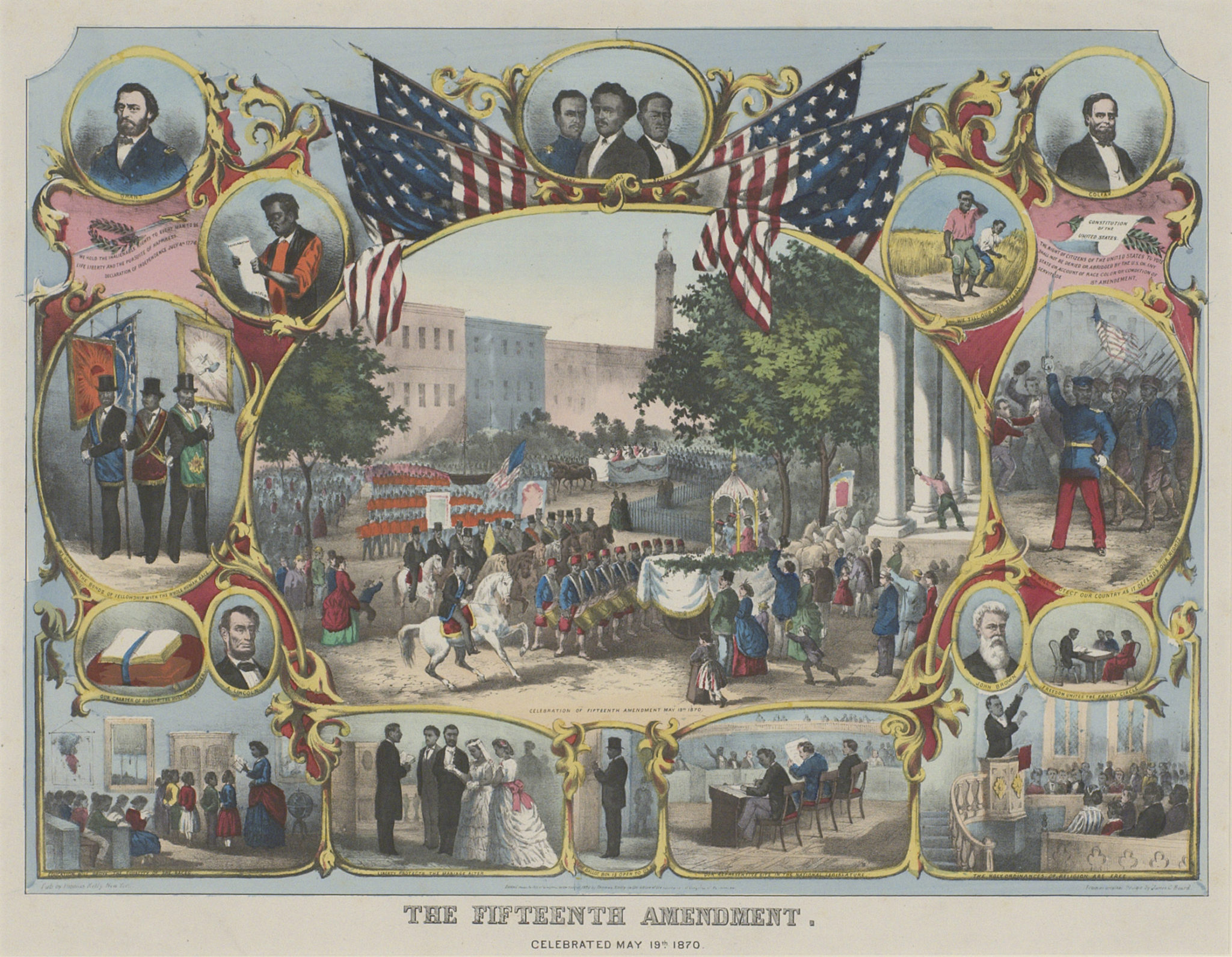

During Reconstruction, African Americans founded independent churches and communities, and many historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) date to this period. Questions about civil rights, voting, and the proper scope of federal power were front and center. Americans passed three new constitutional amendments, dramatically transforming the relationship between the federal government and the states and promising, for the first time, that the U.S. government would protect certain individual rights. The 14th Amendment promises birthright citizenship and basic civil rights, while the 15th prohibits racial discrimination in voting. The 14th and 15th Amendments remain critical to so many facets of American life. Reconstruction was also a tremendously violent period. Many white southerners refused to accept the new order and turned to terrorizing and murdering black southerners and their white allies in an effort to reassert white supremacy.

Congress’s efforts to launch the nation on a new footing during Reconstruction – and to prioritize freedom and equality for all people – were remarkable. Yet for a long time, conventional wisdom held that these policies were a grave mistake, that Reconstruction was an unconstitutional usurpation of state power, and that white southerners were heroic for rejecting federal policy and restoring white domination. That interpretation of Reconstruction prevailed in textbooks and popular culture, and it served to justify the Jim Crow order that endured for much of the 20th century. Most historians have rejected that interpretation since at least the 1960s, but it remains deeply embedded in American culture. It has been heartening to see, over the last five years or so, growing attention to Reconstruction in public life, as communities uncover and discuss their own histories. The National Park Service has devoted growing attention to the period, and in 2017, Barack Obama created the Reconstruction Era National Monument in Beaufort, South Carolina, the nation’s first national park dedicated to interpreting Reconstruction.

SG: I really appreciate studies that take the reader beyond the Treaty of Appomattox and Lincoln’s assassination and focus on effects and repercussions. You co-edited The World the Civil War Made. Your Introduction is titled “Echoes of War: Rethinking Post-Civil War Governance and Politics.” Please comment on your experience in working on this book. Surprises? Changes in outlook? New approaches to teaching the subjects? Affirmation of preciously held viewpoints?

KM: That book was one of the most gratifying things I’ve ever done as an historian. My co-editor, Greg Downs, and I were interested in pulling together and assessing cutting-edge scholarship on the post-Civil War period. Eric Foner’s tremendous 1988 book, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, cast a very long shadow over our field. Foner’s book is a stunning piece of research and writing, and it’s widely influential across all fields of U.S. history. When it came out, one prominent reviewer speculated that there might be nothing further to say on the subject of Reconstruction! Yet scholars continued to produce new work, and we wanted to see what new patterns and approaches we could detect. We deliberately went beyond the usual North/South and black/white dichotomies in Reconstruction scholarship by including historians of the U.S. West and of Native American history. Bill Blair and Penn State’s Richards Civil War Era Center hosted a symposium where scholars gathered, gave papers, and talked about connections across subfields. The participants’ papers were excellent and generated a terrific discussion, and we drew on that stew of ideas to develop the ideas we put forward in the volume’s introduction. Researching and writing history can be very isolating, but this was a collaborative project on many different levels. I hope readers can detect the energy and excitement that went into the volume.

SG: Are you currently working on any special projects?

KM: I’m writing a book about the origins of federal Reconstruction policy – particularly the 14th Amendment – in struggles over the rights of free African Americans in the antebellum North. The book traces how growing numbers of northerners came to believe that racially discriminatory laws had no place in American life. For instance, it highlights the work of black activists and white activists as they worked to strike down racist laws in the Midwest and as they argued that the federal government ought to do more to protect the civil rights of all free persons, regardless of race. The standard story of congressional Reconstruction policy is that Congress was cobbling together responses on a piecemeal basis as it became aware of conditions on the ground in the former Confederacy. This book takes a much longer view, showing that Republican legislators already had very clear ideas about what kind of a nation they would like to live in but did not have the chance to try to put those ideas into practice until the Civil War. This project is introducing me to issues, sources, and historical subfields that are entirely new to me, so I’m having a lot of fun with it.

Kate Masur is the Wayne V. Jones II Research Professor in History at Northwestern University. In 2018-2019, Masur was awarded the National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship.