An Interview with Hon. Frank J. Williams on the Concept of Just War

Sara Gabbard: How far back in history can you trace the concept of Just War?

Frank Williams: In the first millennium, Christians in the Roman Empire, who originally rejected any form of warfare in accordance with their beliefs, ultimately adopted a “Just War” rationale to the use of force against nations to reconcile their beliefs with the needs of the Empire. This rationale identified circumstances in which individuals could resort to force based on a state’s justness of the cause and the purity of motives in employing force. While this Just War tradition focused on regulating the reasons to go to war, it also had effects for the conduct of hostilities, at least when the opposing forces were also Christians. When a war was conducted against non-Christians, these effects disappeared. This conflict would result in an increase, rather than decrease, in brutality. The conduct during the Crusades is an example of this.

As modern Western European nation-states emerged in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and war was fought between nations rather than between leaders, the Just War tradition receded in importance in favor of the use of war alone as an instrument of State policy. Similarly, religion as a basis for limitations on war fighting also receded in importance, and instead scholars identified a “natural law” basis for the applicable rules of international law. Among the leading scholars in this area was Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), whose work, on the Law of War and Peace, is considered a landmark in the development of the modern Law of Armed Conflict. Grotius, “the father of international law,” articulated many of the same principles that applied under the Just War tradition, but based them on his perceptions of natural law, rather than religious law.

Conduct in war, in turn, was justified when it was necessary for success in a Just War. The paradox, however, was that there could only be one just side in a war. The violent acts of the unjustified side were unlawful. Rather than legitimate acts of war, there were illegal acts of violence – assault and murder, trespass, and theft. For the armies of the righteous, by contrast, necessity authorized terrible acts of violence. In Just Wars, armies could lawfully take the goods of the enemy and enslave them. The actions of a Just Warrior were constrained only by the requirements and necessities of victory as limited by one’s definition of Enlightenment principles, i.e., the victor could not try to exterminate its enemy.

When opposing armies were equally convinced of their righteousness, however, the medieval theory of Just War risked taking warfare into the realm of out-of-control destruction.

SG: Saint Thomas Aquinas mentions four requirements for a war to be considered “just.” Please comment on each in the context of the American Civil War.

FW: The first issue is to determine that the reasons for war were just, thus, in Latin, “Jus Ad Bellum,” or “just to war.” Four criteria govern a Just War: (1) authority, (2) cause, (3) intention, and (4) no other alternative.

- Authority

Did the powers starting hostilities have the authority? In Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas insists that “in order for a war to be just” there has to be a “sovereign” with valid authority “by whose command the war is to be waged” because “it is not the business of a private person to declare war” nor “the business of a private person to summon together the people, which has to be done in wartime.” The government of the United States meets this criterion while the government of the Confederacy did not. It is argued that the government of the Confederacy had authority from the states that had seceded from the U.S. and elected to join the Confederate States of America, and, as such, were valid governing bodies. However, the Constitution of the United States, to which all of the states of the Confederacy agreed, gives the right “to raise and support Armies” only to the U.S. government. As president-elect, Abraham Lincoln argued that the Constitution does not provide the means nor does it anticipate that any state or states will leave the Union. Abraham Lincoln, in his First Inaugural Address delivered on 4 March 1861, makes this point:

It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination. Continue to execute all the express provisions of our National Constitution, and the Union will endure forever, it being impossible to destroy it except by some action not provided for in the instrument itself.

- Cause

Thomas Aquinas

“Summa Theologica” by Thomas Aquintis

There must be a just cause for starting a war. What were the reasons to initiate hostilities and what were the opponents’ reasons for engaging in war? There were two for the Civil War: (1) slavery and (2) the U.S. government’s interference with a state’s self-government.

The South believed the cause of the Civil War was the interference on a state’s right to self-government. It, to them, is a contest by the Confederacy against the tyranny of the United States government, as with the colonies against Great Britain during the War of American Independence.

The North, on the other hand, believed the war to be “a struggle to preserve the Union.” Yet, by 1862, it recognized that the only way to preserve the Union was to solve the slavery issue and that it would be necessary to “reconstruct the Union without slavery.” Clearly, the Civil War was a war about slavery.

So which side had a just cause for the initiation of hostilities? Saint Augustine, discussed this as “… one that avenges wrongs, when a nation or state has to be punished, for refusing to make amends for the wrongs inflicted by its subjects, or to restore what it has seized unjustly.” Therefore, if slavery is “wrong,” its sponsor should be punished. The Confederacy “unjustly” seceded from the Union to, in part, uphold the institution of slavery. The U.S. then met the criteria of Jus Ad Bellum and the Confederate States of America did not.

- Intention

Did hostile powers have the correct intentions in commencing war? St. Thomas Aquinas believes that the powers “intend the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil.” There should only be a correction of wrongs on the opponent – not punishment. The Union prevails over the Confederacy for this element of Just War because freedom from bondage became a war aim of the U.S. along with reunion.

- No other alternative

War has to be the final action and last alternative for the war to be just. Even St. Augustine believes that the nation that goes to war is doing so because “it is the wrongdoing of the opposing party which compels the wise man to wage just wars.” Looking at the Civil War, it is clear that it was the U.S. that was required to go to war by force of necessity. All efforts at compromise failed, there was no chance of mediation, and the turbulent 1850s, with: the end of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by passing the Kansas-Nebraska Act permitting the extension of slavery; the Dred Scott case in the Supreme Court that indicated that the black man has no right to be honored by whites; John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859; and failure of the 1860 Peace Conference – all made a “just” war inevitable.

- Summary

The U.S. had the “right to war” in the Civil War and the Confederate States of America did not. The Northern government was the lawful sovereign and the Confederate states were in rebellion. That is how Lincoln treated them, as did his administration. As for just cause, the U.S. wanted to preserve the Union and end the injustices of slavery. The C.S.A.’s insistence on continued slavery, founded on its economic base, was unjust for war.

SG: The Lincoln administration undertook to codify the laws of war consistent with the principles of a Just War. Please discuss.

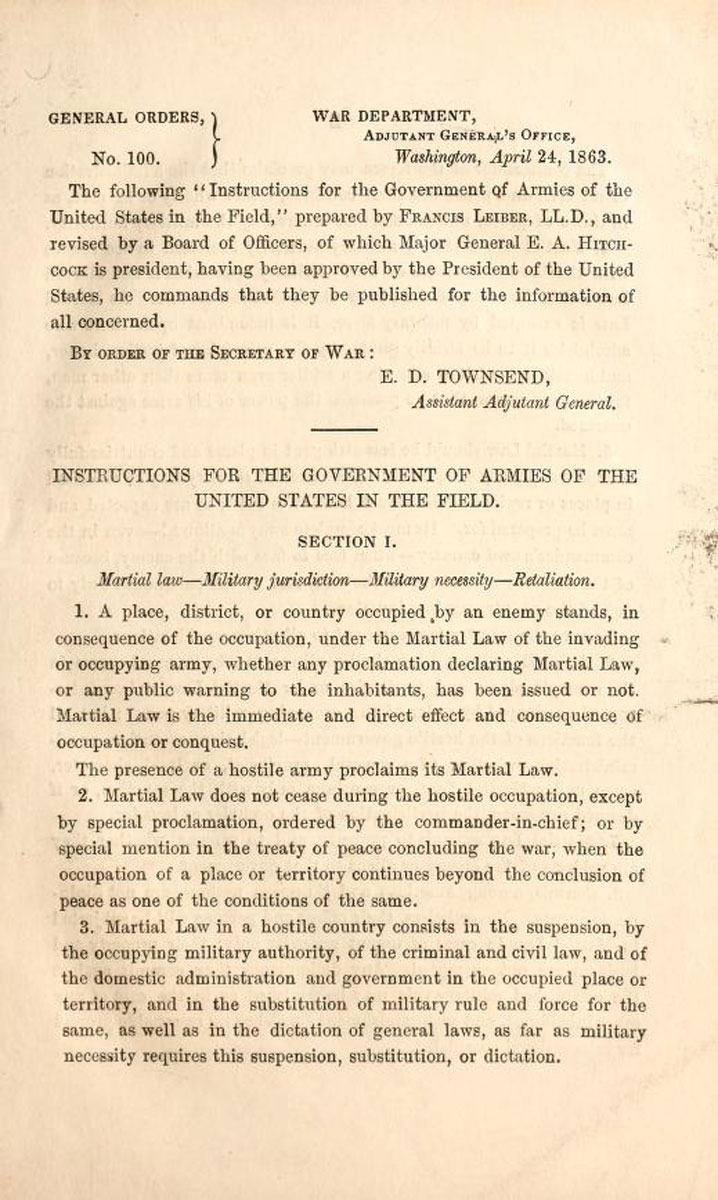

FW: During the American Civil War, Professor Francis Lieber of Columbia College wrote a detailed code of the rules to be followed by Union forces during the conflict with the Confederacy at the urging of Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck and with Lincoln’s support. The rules were intended to secure humane treatment of the population in occupied areas and prevent the already bloody conflict from devolving into unrestrained brutality. Commonly referred to as the “Lieber Code,” Lieber’s Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field were promulgated by President Lincoln as General Order 100 in 1863, and were followed by the U.S. Army well into the Twentieth Century. As the following excerpt shows, the Lieber Code articulates key principles of the law of war, such as necessity and distinction and are reflective of customary international law. The Lieber Code included the following:

* * *

- Military necessity, as understood by modern civilized nations, consists in the necessity of those measures which are indispensable for securing the ends of the war, and which are lawful according to the modern law and usages of war.

- Military necessity admits of all direct destruction of life or limb of armed enemies, and of other persons whose destruction is incidentally unavoidable in the armed contest of the war; it allows of the capturing of every armed enemy, and every enemy of importance to the hostile government, or of peculiar danger to the captor; it allows of all destruction of property, and obstruction of the ways and channels of traffic, travel, or communication, and of all withholding of sustenance or means of life from the enemy; of the appropriation of whatever an enemy’s country affords necessary for the subsistence and safety of the army, and of such deception as does not involve the breaking of good faith either positively pledged, regarding agreements entered into during the war, or supposed by the modern law of war to exist. Men who take up arms against one another in public war do not cease on this account to be moral beings, responsible to one another and to God.

- Military necessity does not admit of cruelty – that is, the infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge, nor of maiming or wounding except in fight, nor of torture to extort confessions. It does not admit of the use of poison in any way, nor of the wanton devastation of a district. It admits of deception, but disclaims acts of perfidy; and, in general, military necessity does not include any act of hostility which makes the return to peace unnecessarily difficult.

* * *

- Public war is a state of armed hostility between sovereign nations or governments. It is a law and requisite of civilized existence that men live in political, continuous societies, forming organized units, called states or nations, whose constituents bear, enjoy, suffer, advance and retrograde together, in peace and war.

- The citizen or native of a hostile country is thus an enemy, as one of the constituents of the hostile state or nation, and as such is subjected to the hardships of the war.

- Nevertheless, as civilization has advanced during the last centuries, so has likewise steadily advanced, especially in war on land, the distinction between the private individual belonging to a hostile country and the hostile country itself, with its men in arms. The principle has been more and more acknowledged that the unarmed citizen is to be spared in person, property, and honor as much as the exigencies of war will admit.

- Private citizens are no longer murdered, enslaved, or carried off to distant parts, and the inoffensive individual is as little disturbed in his private relations as the commander of the hostile troops can afford to grant in the overruling demands of a vigorous war.

Although the Lieber Code was intended only for the U.S. Army, it inspired Germany to adopt it in 1870, and it influenced the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

SG: An interesting thought arises from each of these requirements. Who decides such concepts as legitimacy of the sovereign, “just cause,” and “rightful intention?”

FW: It appears that the Monarch or other leaders of a belligerent nation decide the question of “just cause” and “rightful intention.” John Witte in his Lincoln’s Code gives as example the rising level of violence by 1781 in the American Revolution. This caused James Madison to agree with Thomas Jefferson to increase the level of violence of a “Just War.” The indiscriminate attacks by the British on the towns of New London and Groton, and in the South, made Madison bemoan the “barbarity with which the enemy has conducted the war . . .. The British had acted “like desperate bands of robbers” instead of like a nation at war. The British burned private property and seized slaves, horses, and tobacco. They had, according to Madison, committed “every outrage which humanity could suffer.”

In the War of Independence, the consequences of departing from the Enlightenment principles could have been horrific. Indeed if Madison’s retaliation policy had been adopted, the draconian measures that would have followed could only be imagined. Witte cites the suppression by George II thirty years before the American Revolution against a rebellion in Scotland led by Charles Stuart, heir to the deposed Stuart line of Monarchs. The violence of 1745 was far more draconian than those of the British in South Carolina. Rebels caught with arms would be shot upon capture and many executions were accompanied by disemboweling the victims.

But the boxing-in of General Charles Cornwallis, with a British army of over 7,000 soldiers in Virginia, the dynamic in 1781 changed at a time when the American Revolution seemed to be ending in the colonists’ defeat. General George Washington rushed to Virginia when the French navy under Admiral de Grasse arrived in the Chesapeake with 3,000 men. Cornwallis was then trapped between the Continental Army and the French fleet. Washington had pulled the American War of Independence back from the jaws of destruction.

But what of the requirement that the belligerent – the American colonies – be a recognized entity, rather than a band of guerillas with no organized government? This changed when Great Britain authorized Continental Army prisoners to be treated as prisoners of war – an indicia of a belligerent nation.

SG: Can there still be heroes if a war is considered to be unjust?

FW: I answer this with a qualified “yes.” Take those perceived heroes – at least for the South and the Confederacy and one, despite the contemporary controversy over Confederate monuments, finds strong feelings for Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson, partisan ranger Colonel John Mosby, Generals James Longstreet, Joseph Johnston and others. These are heroes from seceded states, which functioned as the Confederate States of America conducting an unjust war.

The fact is, anyone is a hero who has been widely, persistently over long periods, and enthusiastically regarded as heroic by a reasonable person, or even an unreasonable one. There is also an element of idiosyncrasy as a legitimate part of hero worship as we have seen in the myth of the “lost cause.”

Hero movements can be frequent, continuous, and full of peaks and valleys. British Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, remarked:

Contemporary judgments were illusory; look at Lincoln’s case, how in his lifetime he was thought to be a clumsy lumbering countryman, blundering along without knowing where he was going. Since his death his significance has grown steadily. [Woodrow] Wilson, on the other hand, was for a short spell looked up to like a god, and his fame will gradually shrink. Lincoln is Wisdom, and Wilson is Knowledge.

Heroes in an unjust conflict still evoke wonder or admiration or respect or in some cases sympathy. I think the nub of the issue here is to judge by example and not so much by definition.

The South found a hero in Robert E. Lee. He was a noble and virtuous man, like Abraham Lincoln. But the contrast in their motivations was significant. The two men had quite different ideas about the individual states. Lee was a true hero – despite commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, a herculean effort for an unjust belligerent. He insisted on making possible for others the freedom of thought and action he sought for himself.

SG: Please use the above mentioned concepts to argue that the Civil War was “just” or “unjust,” from the standpoint of both Union and Confederate points of view.

FW: Without exactly articulating it, Abraham Lincoln had come to his decision for emancipation by comprehending what the Enlightenment meant for a Just War. “The will of God prevails.” “In a great contest,” Lincoln wrote in one of his “Fragments” – later to be included in his Second Inaugural Address – “each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God.” But of course the contending sides could not both be right. “Both may be, and one must be wrong,” Lincoln wrote to himself, because “God cannot be for, and against the same thing at the same time.” The great problem, he concluded, was that people could never know for sure whether God had chosen their side or the other. In just a few words, Lincoln had articulated the concept underlying the Enlightenment rules for civilized warfare. Human beings could never know for sure that they comprehended God’s justice. The concept of legal limits on war was an indication that both sides believed they were in the right. Did not war itself require certainty about the justice? Lincoln continued, “I am almost ready to say this is probably true – that God wills this contest.” By now Lincoln had decided on emancipation.

In his decision on emancipation, Lincoln had chosen a just side of the contest. In language that was Lincoln’s own, his proclamation announced that on January 1, 1863, all people held as slaves within a state in rebellion against the United States would be “forever free.” The armed forces of the United States, the president resolved, would thenceforward “recognize and maintain the freedom” of the former slaves and would “do no act or acts to repress” the freed people “in any efforts that may make for their actual freedom.” He also invited free African-Americans to contribute to the war effort by enlisting in the armed forces.

SG: For readers who are interested in this topic, can you recommend a few books?

FW: Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War (Harry Stout); The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Mark Noll); This Republic of Suffering (Drew Gilpin Faust); Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History (John Fabian Witt); and Lincoln on Trial: Southern Civilians and the Law of War (Burrus Carnahan).

Epilogue

“If there is one thing…that will not vary, if there is one firm rock on which we can rely, it is that to make our way through the next crisis will require deliberations on the nature of Just Wars: deliberations like those Lincoln engaged in during the summer and fall of 1862 as he prepared for Emancipation and set the stage for the code that followed. The laws of war require commitment to act on our best notions of justice in a world beset by violence and danger. Sometimes that commitment will require the use of force, not withstanding all war’s perils. But when we do use force, we will have to balance our ideas of justice with humility about our ends.

. . .

…Lincoln…in his Second Inaugural Address …promised to win the war but confessed the sins of the North nonetheless. Lincoln’s General Orders No. 100 aimed to establish a framework for making decisions in wartime that would make salient both of war’s twin imperatives: resolve and humility. All too often Americans have failed to live up to the example Lincoln set. How could we not? But what is equally striking – what is remarkable and enduring – is that men and women have worked ever since to preserve the framework he helped to establish.”

(Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History (John Fabian Witt) p. 373.)

Frank J. Williams is the founding Chair of The Lincoln Forum and the retired Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court. He teaches at the U.S. Naval War College and serves as a mediator and arbitrator. In 2003, he was appointed a judge of the U.S. Court of Military Commissions to hear appeals from enemy combatants detained at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.