An Interview with Allen Guelzo

Sara Gabbard: When you are “on the road” lecturing about Lincoln and the Civil War, what questions do members of the audience ask most frequently? Do responses from your students reflect the same interests?

Allen Guelzo: Far and away, the most-frequently-asked question I encounter from audiences is, “Would things have been different if Lincoln had lived?” What they mean, in most cases, is, would a Lincoln-managed Reconstruction have healed the nation’s wounds more effectively than the one we got, as managed by Johnson and Grant, and spared us a century-and-a-half of racial suffering and turmoil?

The answer is maybe. Even that is mostly based on the not-unreasonable assumption that nothing Lincoln would have done could have been worse than what Andrew Johnson did. But in real terms, Lincoln faced some serious problems in Reconstruction that were almost as formidable as the wartime ones. First, he needed to move the freedpeople toward civil equality, starting with the vote. After all, the Constitution knows no category of semi-citizen; you’re either a citizen or an alien, and with the end of slavery, it would have been unthinkable to classify the freedpeople (180,000 of whom had fought for the Union) as mere aliens. Furthermore, Lincoln would need their votes, since Reconstruction would bring white Southern Democrats back into the political life of the nation (and likely in alliance with their old Northern Democratic allies). Black voters would create for Lincoln a new political constituency in the South to offset white Democratic power, and their voice would be a necessity if the Republicans’ wartime measures (tariffs, the national banking system, the transcontinental railroad) were not to be overturned.

But that created the second problem — how were the freedpeople to be enfranchised, and who would enforce it? No one in the South was going to take this sitting down; there would have to be some element of military oversight, and that would continue to run up the costs of the war. One of the painful lessons we learned out of the Iraq War (and should have learned after World War One) was that you can’t simply walk away after the shooting stops. Lincoln did not want military occupation. He was not a military-minded person, and he was already fearful of the costs of prolonging military expenses at the war’s close. But he would not have had any other choice, given the behavior of the defeated Confederates. As it was, I believe that we broke off military occupation of the South entirely too quickly. We needed to foster, over at least thirty years, the emergence of a new generation of Southern leaders, black and white, who could (as Lincoln said) live themselves out of the old patterns and into the new. But the investment, in time, energy, and money, would have been (to borrow a Lincoln term) “heart-appalling.”

Finally, there is a third limitation on what Lincoln could have done: he would have left office in March 1869, which is not a lot of time in which to effect a Reconstruction. Granted, there was no constitutional inhibition at that time on his running for a third term, but there remained a general sense that this sort of thing wasn’t done (as Ulysses Grant learned when he made noises to that effect).

Curiously, this is not a question often asked by students in the classroom. But I suspect this is because they’re often coming to grips for the first time with these events, and haven’t yet acquired the perspective to ask what if.

SG: Have your students impacted the way that you view the subjects that you are teaching?

AG: I was asked by a Princeton undergraduate recently: why do you always wear a coat and tie to class? Because, I said, I have the most wonderful students in the world, and this is my way of saluting them. And I really have enjoyed some of the most marvelous students, some of whom already are stepping into significant scholarly careers: I think particularly of Brian Matthew Jordan (whose Marching Home was a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize in History), Skye Montgomery, Zachary Fry, John M. Rudy, and Evan Rothera. There are also many who have gone into other pursuits: William Holiman, Isaac N’gang’a, Nick Lulli, Kees Thompson, Ben Foulon, Richard Hildreth. But I cannot say that they have impacted how I teach. I’m afraid I may have intimidated them too much, because they have always been so polite and circumspect. Or maybe, I’ve just been too obtuse to realize how they’ve affected my outlook. I wish I could rule that one out, but I know better.

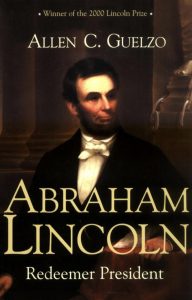

SG: The first of your books that I read was Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. After 20 years, it is still a favorite.

AG: I’m delighted to know that. I’ve been in discussion with Eerdmans about producing an anniversary edition, with some new and updated material. Perhaps it will be worth getting re-acquainted with the book.

SG: The subject matter for your books on Lincoln varies greatly. How do you determine the specific topic which you wish to pursue?

AG: Mostly, I look to ask the questions that haven’t been answered, or better, even asked. Redeemer President was more of a response to an urging from others than an initiative of my own, but once Redeemer President was finished, I realized that the Lincoln field held out more unanswered questions than people suppose. Hardly any reviewer fails to begin a review of a Lincoln book without some useless comment about how many Lincoln books there are and so how can another one be a real contribution. That’s pure absurdity. The Lincoln field is like a meadow over which many wagons have been driven, but most of them follow the same narrow ruts the others have created, while vast stretches of the meadow roll away to the distance, untouched. I have a list of Lincoln book topics that, I loudly lament, have lain unexamined. In fact, many of them are the same topics James Garfield Randall begged students to take up in his famous 1936 address, “Has the Lincoln Theme Been Exhausted?” and that was almost a century ago.

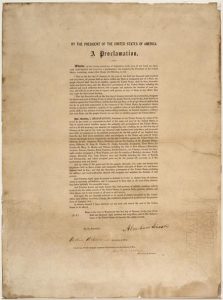

After Redeemer President, I remember sitting at a luncheon in connection with the Abraham Lincoln Institute of the Mid-Atlantic in Washington (now simply the Abraham Lincoln Institute) in the midst of their annual symposium in 2000, and thinking to myself: what should I write next? And it came to me almost in a flash, “There’s been no really serious book about the Emancipation Proclamation!” There was only John Hope Franklin’s brief The Emancipation Proclamation, and that had been written in 1963. So, I pitched heavily into that, and in 2004 produced Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America for Simon and Schuster.

At the end of that project, it occurred to me that the sesquicentennial of the Lincoln-Douglas campaign of 1858 was only four years away. There was, of course, the great Harry Jaffa’s Crisis of the House Divided (1959), but that was a political scientist’s analysis of the debates; I wanted to take in the whole contest, from June, 1858, until January, 1859. And so that became Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (2008). Once done with Lincoln and Douglas, the Civil War sesquicentennial was almost upon us, and I turned without a second thought to writing Gettysburg: The Last Invasion.

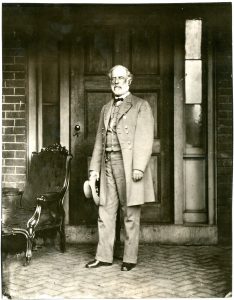

I have just now finished the manuscript of a Robert E. Lee biography, and that, too, was an attempt to answer a question I thought had been ignored: how do you write the biography of a man who commits treason? Besides, having written three large Lincoln books (along with four smaller ones), I thought it might be interesting to look at the only other figure on the Civil War landscape who seemed to be in any way equal to Lincoln in significance, and that was Lee.

SG: Which book was the most difficult to research?

AG: Gettysburg: The Last Invasion was an immense challenge because so much existed in the way of memoirs, reminiscences, and histories of the battle, some of them written before the last of the battle’s dead had been buried. I spent a very long time reading through personal narratives and regimental histories, knowing full well that any one of these I neglected would surely be seized upon by the army of eagle-eyed Gettysburg buffs as some form of fatal omission. What guided me through this vast literature was a determination to see the battle through the eyes of the 19th-century, and cognate 19th-century wars. Hence, even as I was steeping myself in Gettysburg sources, I was reading deeply in 19th-century European military tactics and procedures, and finding a wealth of comparative insights: for instance, the use of column and line, the efficacy of artillery, the purposes of cavalry, the aversion to street-fighting.

Too much American writing on the Civil War, and on Gettysburg, is embarrassingly parochial. We often forget that our Civil War era was also the era of the Crimean War, the Schleswig-Holstein War, the Indian Mutiny, the Tai-ping Rebellion, the Austro-Prussian War and (at the outside) the Franco-Prussian War. American soldiers lived in those times and imbibed those examples. For instance: why did the Union and Confederate armies never develop heavy cavalry, relying entirely on light cavalry throughout the war? Why was Pickett’s Charge not the hopeless, reckless fling that it is so often portrayed as being? The answers are in the overall context of 19th-century warfare.

Gettysburg: The Last Invasion was a challenge of depth; the Lee biography has been a challenge of space. Unlike the papers and letters of Lincoln, Grant, Jefferson Davis and Andrew Johnson, there is no easily-available scholarly edition of the letters and papers of Robert E. Lee. Partly, this is because Lee was an indefatigable letter-writer, sometimes writing several multi-page letters a day, and probably composing 4,000 of them during his adult life. Creating such an edition would be the work of an entire career. What’s worse, these letters are scattered in archives and libraries all across the continent, literally from the J.P. Morgan Library in New York to the H.E. Huntington Library in San Marino, and they all required patient tracking-down, visiting, and copying.

There are several conveniently-large collections at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond, at Washington & Lee University, and at the Library of Congress; on the other hand, there are important Lee materials still in private hands, some of which pop-up incontinently on on-line auction sites. Mercifully, I had wonderful assistance at all of these places – John McClure in Richmond, my dear friend Lucas Morel at Washington & Lee, Michelle Krowl at the Library of Congress. But all the same, managing Lee’s writing was a mammoth task. I had to create my own index of Lee letters: it runs out to 103 pages of single-spaced entries. That’s only a beginning.

Lee is a challenge in another way, because he is a personality very unlike Lincoln. He was not a profound thinker, and not very much of a reader, and he alternated emotionally between a desire for security and a desire for independence. He was no enthusiast for either slavery or secession. But like many elite Virginians, he simply averted his eyes from any personal responsibility for slavery, and allowed himself to be sucked into the secession movement under the impression that he could somehow become an agent for mediation, as well as protecting the family’s Arlington property. He was wrong about both.

Lee is also a challenge because he was an engineer rather than a lawyer like Lincoln, and that demands a biographer acquire certain mastery of technical finesse in order to be able to understand Lee’s career, which was spent mostly in the U.S. Army’s Corps of Engineers. (I never thought I would read a textbook on coastal engineering, but for Lee, I did). He served in the Mexican War, and with conspicuous success, but as a staff officer. People are surprised to realize that Lee only commanded troops in action for the first time when he was given charge of the company of Marines that suppressed John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. After the war, as president of Washington College, Lee remarked that the worst mistake of his life had been “to take a military education.” He might have been happier as a civil engineer, but he could not bring himself to abandon the security of the Army. He was probably at his happiest as president of Washington College in the last five years of his life, when he was remarkably successful and progressive as a curriculum innovator and a fund-raiser.

SG: Please tell our readers about your program at Princeton.

AG: One of the two hats I wear at Princeton is that of Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities. The Council is not really a “council,” but a department of its own, and is interdisciplinary across the humanities, so that I get to teach a variety of courses under its umbrella. My status as a Senior Research Scholar leaves me a wide variety of choices, and that especially means the freedom to do a lot of writing. My other hat is the Director of the James Madison Program’s Initiative on Statesmanship and Politics. The James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions was the brainchild of Robert P. George, the McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton, and has grown over twenty years to embrace both graduate and undergraduate students in fellowships and other programs connected to the American political tradition. The Madison Program is “dedicated to exploring enduring questions of American constitutional law and Western political thought,” and especially “to examining the application of basic legal and ethical principles to contemporary problems.” The Initiative on Statesmanship and Politics is still under construction, and will focus on the investigation of models of statesmanlike leadership in political life, and what qualities distinguish it from other forms of political activity.

Lincoln, of course, will be a major figure because he gives us clues to the definition of statesmanship through several remarkable qualities: by his cultivation of an understanding of issues and contexts…by visibility to the nation…by his love and reverence for the rules and workings of political life…by mastering his organization…by converting personal liabilities into political assets…by his persistence…and by his resilience. Those qualities are also the particular preserve of democratic statesmanship, and they differ in nature from the qualities required by monarchical leadership, which is about honor, style, and the acquisition of power, or bureaucratic leadership, which is about efficiency, competence, and procedure.

SG: A website refers to you as specializing in “American intellectual history from 1750 to 1865.” Why those beginning and ending dates?

AG: That’s because I am, at the meat-and-potatoes level, an American intellectual historian. I am, and have always been, fascinated by American ideas, believing that (as the Psalmist said), “As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he.” I actually only backed into doing the American Civil War to the extent I have because of Lincoln, and only backed into Lincoln because of the attraction he offered as a man of ideas.

Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President is, after all, an intellectual biography of Lincoln, and it’s modeled on other species of that genre. As an undergraduate, I fell under the spell of Perry Miller, and especially his great intellectual biography of Jonathan Edwards, so that set me on the course of following the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century as the era of Edwards’s greatest prominence. My dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania, under the eminent intellectual historians Bruce Kuklick and Alan Kors, was on Jonathan Edwards and the problem of free will and determinism in 18th-century America. Once I had the PhD in hand, my first instinct was to write a second book, taking the story of American ideas on that knotty philosophical problem forward from 1858 to the present. This is what brought me alongside Lincoln. I knew that Lincoln had more than a few things to say about fatalism and determinism, and I thought it would be boundlessly clever of me to include Lincoln in a book whose cast of characters was otherwise theologians and philosophers. I ended-up writing a paper about Lincoln’s “Doctrine of Necessity” which was more successful than I had anticipated, and led to the suggestion I write Redeemer President. Once I had my hand in the Lincoln cookie jar, I couldn’t get it out. I’ve never gotten back to writing free-will-and-determinism 2.0.

Not that I have any complaint about that. The group of scholars clustered around the study of Edwards was a very tight circle; my experience of the Lincoln fraternity was entirely different. People like Michael Burlingame and Doug Wilson welcomed me, a stranger, with open arms in the 1990s. And I have made such wonderful friends among the Lincolnites – Lew Lehrman, Joe Fornieri, Tom Schwartz, Tom Klingenstein, Bill Harris, Jon White, and so many, many more. (Yes, you too, Sara!) I sometimes think the generous spirit of Lincoln insinuates itself into those who study him.

I surprise my students when I tell them that I never took a course on the Civil War on either the undergraduate or graduate level – or on Lincoln, for that matter. But I have always had an interest in Lincoln, going back to my childhood, when I pestered my grandmother to buy me a comic-book biography of Lincoln (it was the Classics Illustrated no. 142, and yes, I still have it). I wrote my high-school senior thesis on Lincoln and the election of 1860, and drew the ticket to narrate Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait with my high-school orchestra under my much-loved music director, Luca Del Negro. (Forty years later, I narrated it again under Del Negro’s direction with the Rose Tree Pops Orchestra – what a reunion that was). But somehow I never thought of making a serious business out of studying Lincoln. Far from pursuing Lincoln, in my first year in college I was a music composition major – that is, until I discovered that I really didn’t have the talent for it! But I have always grabbed for any opportunity to narrate Lincoln Portrait, and I always take delight in assuring the conductor that, no, I don’t need any special cues, I can read the score myself, thank you. In 2009, for the Lincoln Bicentennial, Michael Colburn, then music director of the U.S. Marine Band (“The President’s Own”), invited me to serve as narrator, not only for Lincoln Portrait, but for the world premiere of Roland Bass’s A New Birth of Freedom in Washington. I could not imagine a more exciting way of celebrating Lincoln’s 200th.

SG: Please rate Lincoln as a Commander-in-Chief.

AG: I’ve come to believe that Lincoln was in many ways a better president than he was commander-in-chief. Lincoln had very little experience in military matters and very little taste for them (something which was reinforced by his Whiggish politics, since the Whigs were the enemies of the “military chieftain,” Andrew Jackson). As president, he assumed that he could master military affairs the same way he had mastered the law – by reading the standard textbooks, which he proceeded to borrow from the Library of Congress.

As the son of a career Army officer and the father of another, I can testify that this is not the path to military understanding. If anything, he learned all the wrong lessons from the textbooks. He was convinced that a single Jacksonian demonstration of military determination would be enough to scare the Confederates into shivering imitations of the nullifiers of 1832; that did not work at Bull Run. When he called George McClellan east to take command, McClellan spent most of his first year creating a fortification ring to protect the capital, and training an army for invasion – both of which were necessary, and both of which Lincoln mistook for dithering. McClellan then formulated a highly-sophisticated combined-operations strategy for besieging and capturing Richmond, based on the models used by the British and French in the Crimea. Lincoln saw no virtue in this whatsoever, and wondered why McClellan didn’t simply smash straight overland at the Confederate army.

The miserable failure of the Peninsula Campaign convinced Lincoln that any further suggestions for combined operations of the McClellan sort were mere excuse-mongering, and he demanded that McClellan’s successors – Burnside, Hooker, Meade – conduct his favorite idea of a straight-on, heads-down overland campaign. He demanded the same thing of Grant, even though Grant was skeptical of an overland campaign. Grant nevertheless did what he was told. But by the time he reached Cold Harbor, it was clear that an overland campaign was not working. Happily, Grant had built up enough political capital with Lincoln (something McClellan, a Democrat, never tried to do) that he was given a free hand to change directions, which he did by shifting the entirety of his campaign across the James and Appomattox Rivers and locking Petersburg and Richmond in a siege.

The truth was that armies, by the mid-nineteenth century, had grown to such size, that their logistical demands made impossible their survival anywhere farther than twenty-five miles from a major supply center or railroad. Lee understood that, which is why he often said that if Grant was able to besiege and capture Richmond, it would only be a matter of time before the Confederate army went the same way. It was. Once Richmond fell, Lee’s army lasted exactly seven days on the run. Headlong battles of the sort Lincoln had read about in the textbooks were a thing of the Napoleonic past, at least in terms of being the hinge that wars turned upon, and in fact the so-called “decisive battle” associated with Napoleon may have been obsolete by his time, too. On the other hand, Lincoln trusted Grant, and trusted him enough to let Grant have his own leash. That was what won the war.

SG: You have won the coveted Lincoln Prize three times. Please comment on the circumstances which surrounded the decision to write each book.

AG: I’ve already hinted a little bit at these circumstances, and in the case of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and Lincoln and Douglas, the initiative came from me, channeled to Simon & Schuster through my agent, Michelle Rubin. Redeemer President was different. That book was the offspring of the mid-1990s, when I was still doing the work of an American intellectual historian, and teaching American history courses at Eastern University. I had never planned to write a book about Lincoln, but the impact made by the paper I wrote on “Lincoln and the Doctrine of Necessity” generated a call from Chuck van Hof, then the editor at Wm. B. Eerdmans in Grand Rapids. Eerdmans has a multi-volume series, the Library of Religious Biography, and Chuck suggested I write a book on Lincoln’s religion. I said no. I was aware that a great deal had been written about Lincoln and religion, much of it very mawkishly done, and I didn’t want to sink into that swamp. Van Hof called me a second time; a second time I said no. He even signed up a mutual friend, Mark Noll, to make the request; I still said no. Finally, Van Hof came back to me one more time, telling me that if I didn’t take on the project, he would give it to Professor G——-. I knew Professor G——–, and shuddered at the likely result. So, I made a counter-offer: let me write an intellectual biography of Lincoln, speaking to the general intellectual milieu of his time, of which religion would be a part. Van Hof was agreeable, and so Redeemer President happened.

I originally wanted the title (which was borrowed from Walt Whitman) to read, Redeemer President: Abraham Lincoln and the Ideas of Americans. But Van Hof overruled me, and it became Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President – largely, I suspect, so that Lincoln’s name would be one of the first two words in the short-title distributors use in their catalogs. Books, after all, are a business, just like Leonardo’s paintings. Eerdmans nevertheless did a lovely production job. The dust jacket featured the Edwin Marchant portrait of Lincoln from the Union League of Philadelphia, and the endpapers show the handwriting of the Second Inaugural. There are no maps or illustrations, and originally, in keeping with the format of the Library of Religious Biography, no footnotes. At the last minute, however, it was decided that some form of notation was necessary, so I had to go back and reconstruct all the notes, in the form of running endnotes for each chapter.

Gettysburg: The Last Invasion was one of those books that the hour (meaning, the impending sesquicentennial) seemed to ask for. I finished the manuscript at the end of August, 2012, and it was in production and ready for release the following May, just in time for the anniversary of the battle. I had drawn maps for Lincoln and Douglas, but GTLI required much, much more in that way, and much more in the way of illustrations. I was fortunate in having the co-operation of the Adams County Historical Society and of William Frassanito for the illustrations. Not surprisingly, I spent a great deal of that summer doing nothing but talking about the battle of Gettysburg.

What did surprise me was the book winning the Lincoln Prize – having won the Prize twice before, I assumed that this would probably discount any likelihood of making what Brian Jordan called a “three-peat.” But then, one fine February morning, Brian strolled into my office and broke the news. No one could have been more astonished than myself. But the greatest astonishment was yet to come, when GTLI won the Guggenheim-Lehrman Military History Prize, the Fletcher Pratt Award and the Richard B. Harwell Award. I attended the Guggenheim-Lehrman award ceremony with no idea of who the winner might be, and found myself in the company of a bevy of military historians whose work I had come to admire profoundly – Richard Overy, Saul David, Hew Strachan. I could not imagine someone who had spent so much time writing about philosophers deserving a place at a table featuring such giants. So, I remember sitting, utterly unprepared, in the front row of the auditorium of the New-York Historical Society, as Andrew Roberts stood at the podium and said, “And the winner is, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion.” My mouth literally dropped open. I almost blurted out, “No, you don’t mean that.” I was asked to come up to the podium and say something, but I was emotionally dazed, and to this day I have no idea what I actually said.

SG: What is your next project?

AG: I’ve devoted the last six years to writing a biography of Robert E. Lee, which looks like it will be of about the same physical proportions (as a book) as GTLI. I want now to get back to Lincoln, and I have in mind a book which will speak to Lincoln’s ideas about democracy. Curiously, Lincoln used the word democracy sparingly. His most extended example is the famous note, “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” Yet, no one in our history has come closer to embodying what we think of as the best in our democracy. The question is whether democracy, as it worked in Lincoln’s world, still works in ours.

Allen Guelzo is Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University.