Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, An Interview with Allen Guelzo

Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President

Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President

An Interview with Allen Guelzo by Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Please explain the circumstances of this new edition of your book.

Allen Guelzo: I have to answer this a little shamefacedly. I did it with a question. Four years ago, I was delivering a lecture on Lincoln in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the headquarters of Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President’s publisher, William B. Eerdmans. One of the Eerdmans editors attended the lecture, and we struck up a conversation about how the book has stayed on their best-seller list over the last two decades. That prompted me to suggest that maybe it was time for an “anniversary” edition of ALRP.

At the back of my mind, I was thinking principally about how I could correct some of the bloopers in the text – and yes, Sara, I have to admit, that like all Lincoln books (except Michael Burlingame’s) there are some bloopers. So, the motives were mine, and they were prompted by self-interest – which is what, you’ll remember, Lincoln said most action was prompted by, so I’m still being a consistent Lincolnite.

SG: I have always been interested in your description of Lincoln’s somewhat ambivalent feelings about Thomas Jefferson. Please comment.

AG: Lincoln grew up in log-cabin poverty, among the 90% of Americans who then farmed for a living, and though later political promoters made the most they could of his common-man origins, Lincoln disliked talking about them. “I have seen a great deal of the backsides of the world,” was how he began and ended discussions of his origins. Charles Ray (of the Chicago Tribune) opened a correspondence with Lincoln after the 1858 campaign in which Ray delicately hinted his suspicion that Lincoln had not been born with a silver spoon in his mouth.

Ray had no idea how right he was, and that’s an indication of how tight a curtain Lincoln wanted to draw across his upbringing. Even as a presidential candidate, Jesse Fell and John Locke Scripps had to twist biographical details out of him. For Lincoln, the world in which he had grown up was violent, crude and drunken, and he left it behind as soon as was legally entitled to. He admitted to Fell that “If a straggler supposed to understand latin, happened to sojourn in the neighborhood” in which Lincoln grew up in Indiana, “he was looked upon as a wizzard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three; but that was all.”

We often romanticize the frontier. But the truth is that the West of Lincoln’s youth was the place that all the square pegs who didn’t fit into Eastern round-holes were sloughed-into – people like Jim Bowie, Jim Bridger, Joseph Smith, Davy Crockett. Dennis Hanks told Herndon that the prevailing spirit of Lincoln’s adolescent environment could be summed-up in the snarky adaptation of the patriotic song, Hail Columbia:

Hail Columbia, happy land

If you ain’t drunk, I will be damned

What Lincoln wanted was self-transformation, and that meant putting as much distance as he practically could between himself and frontier life. Transformation was what he read about in the books he pored through; that was what drove him to commerce rather than agriculture; and that what was what made him an ardent Whig and an opponent of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic party. Jefferson never tired of telling people that agriculture was the only pursuit which guaranteed independence and virtue.

“Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people,” Jefferson wrote in his Notes on the State of Virginia, “whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue.” Jefferson regarded commerce and manufacturing with an evil eye: commerce was about tricking people into buying things they didn’t need or could make for themselves, and thereby putting themselves into debt, while manufacturing reduced citizens to wage-earners who were entirely at the mercy and manipulation of the manufacturers. This outlook led Jefferson into conflict with Alexander Hamilton, who saw commerce and manufacturing as the only way the infant American Republic could escape dominance by Great Britain.

That conflict set up a second generation of political strife between Jefferson’s heirs, Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party, and Henry Clay, the founder of the Whig Party. Like many Whigs, Lincoln saw commerce as the path to a new and better life, and his career as a trial lawyer was largely devoted to smoothing the pathways of commerce. Jefferson and Jackson might talk about the glories of agriculture, but both of them were enormous landowners, not the actual pushers of plows, and the plows that were pushed on their properties moved by the muscle of slaves.

Even worse, in Jefferson’s case, there were wide-spread stories already in circulation of Jefferson’s sexual exploitation of at least one slave woman, Sally Hemings.

All of this struck Lincoln as the rankest hypocrisy, a hypocrisy which ran down to the very bases of the Democratic program. “Mr. Lincoln never liked Jeffersons moral character,” Herndon wrote in 1866. Herndon once told Ward Hill Lamon that “Mr. Lincoln hated Thomas Jefferson as a man,” and in 1844, Lincoln seems to have written a scathing editorial piece during that year’s presidential election, describing Jefferson’s character (and thus the character of Democratic politicians in general) as “repulsive.” That was in 1844, though, when Lincoln was still the highly partisan Illinois Whig, happy to hit whenever he could below the political belt.

A decade and a half later, Lincoln rose from the partisan cocoon as the idealistic enemy of slavery, and as fuel for that opposition, Lincoln turned almost naturally to Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence as the rock on which slavery had to shatter. In April, 1859, he wrote in response to a speaking invitation from Boston that “The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society” and would serve as “a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.” I suspect Lincoln was conscious of performing something of a volte-face this way: in that same response, he suggests that Jefferson’s political heirs “have changed hands” and thus left Jefferson to be claimed by the new Republican party. This is, of course, a political and intellectual stretch.

But it does indicate that by the time Lincoln emerges as an anti-slavery leader, he needs Jefferson the champion of liberty, and will quietly dispense with the personal Jefferson whose conduct and other ideas so offended him. At a singular moment in 1863, when Salmon Chase urged Lincoln to extend the Emancipation Proclamation unilaterally to the Border States, Lincoln replies with Jefferson’s words: “Would I not thus be in the boundless field of absolutism?”

SG: Please explain your statement that Lincoln “lived most of his life as a Victorian.”

AG: The Victorian age marked the triumph of the middle classes – the bourgeoisie, if you will. Rising on the wings of the Industrial Revolution, the ranks of the bourgeoisie expanded tremendously, and so did their political power. Even monarchs, like Queen Victoria, found themselves shedding the old trappings of aristocracy to dress and speak like their middle-class subjects. At any time before 1700, this bourgeoisie would have been unimportantly small in number, concentrated in the cities (hence the term bourgeoisie, which is kin to the German burgher, or city-dweller), and despised for dirtying their hands in trade.

The bourgeoisie could never be genteel; they could only be tolerated, sometimes despised, and frequently sneered-at by their landowning betters. Even as late as Jane Austen’s Emma, her bourgeois characters might be “friendly, liberal and unpretending,” but they were also “of low origin, in trade, and only moderately genteel.” This changes immeasurably in the Victorian era, and Lincoln is very nearly as good a marker of this as anyone else in 19th-century America. Although Lincoln never entirely shed his backwoods accent and poor-boy mannerisms, he acquired by middle age all the signs of the successful bourgeoisie: he married into a successful commercial family, owned a substantial but unpretentious house, lived and worked in a city, and acquired manners which are sufficient to mark him as “genteel.”

When Jane Martin Johns met Lincoln in 1849, she found that “the ungainliness of the pioneer, if he ever had it, had worn off and his manner was that of a gentleman of the old school, unaffected, unostentatious, who ‘arose at once when a lady entered the room, and whose courtly manners would put to shame the easy-going indifference to etiquette.’” Above all, Lincoln became a lawyer, and a successful one at that. In the eighteenth-century, American lawyers were gentry, and mostly policed the morals of communities. By Lincoln’s day, lawyers have become what Charles Sellers called “the shock troops” of commerce, and few were better at administering and managing those shocks than lawyer Lincoln.

SG: In the last sentence in the Introduction to the original book, you state: “But then again, the strife of ideas brought us Abraham Lincoln.”

AG: As I was writing ALRP, I was reading the philosopher Richard Rorty’s Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, which deplored the baleful influence Rorty believed that ideas had in motivating people to argument and conflict. As the good offspring of the pragmatists – William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, John Dewey – Rorty believed that people should pay more attention to what made their lives better, rather than pursuing mental blueprints for what was right or true or beautiful, or insisting “that the world or the self has an intrinsic nature.” I do not find this philosophically appealing, and neither would Lincoln. He took for granted that the universe (and human beings in it) had been made a certain way, and that the task of ideas was to discover that pattern, not merely make pleasant compromises or experiments with our circumstances. “Moral principle is all, or nearly all, that unites us,” Lincoln said, and he had particularly in mind the natural law principles enshrined in the Declaration – that everyone is hard-wired with certain inherent rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

What made slavery criminal was the gross violation slavery represented of natural law. Even “the ant who has toiled and dragged a crumb to his nest, will furiously defend the fruit of his labor, against whatever robber assails him.” It’s a natural instinct. So, likewise, even “the most dumb and stupid slave that ever toiled for a master does constantly know that he is wronged.” Slavery was to be opposed because it violated in the most outrageous way these principles of natural law – not because it was merely inconvenient or (in the term of John Rawls) unfair, but because it was wrong.

The danger Rorty (and his pragmatist forerunners) saw in ideas was that people make compromises over inconveniences; they make wars about ideas. It was the abiding insistence of the pragmatists that ideas had resulted in the bloodshed of the Civil War and not much more than that (a complaint Louis Menand made plain two years after ALRP was published in his The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America). Hence, Rorty wanted to wean us off our fascination with ideas as too likely to bring on conflict. My response was to say that if we feared “the strife of ideas,” we would also have to give up Lincoln.

People often speak of Lincoln as a pragmatist. But they are using the word pragmatist as a synonym for practical, not in its philosophical sense, as what William James called “a doctrine of relief.” Lincoln could hardly have disagreed more vehemently with that meaning of pragmatism.

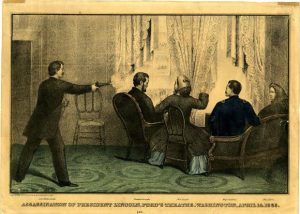

SG: When reporting on the public response to Lincoln’s death, you quoted Jane Addams as saying that, after witnessing her father’s emotional response, she said that she was too young to fully grasp the situation but she “dimly caught the notion of the martyred President as the standard-bearer to the conscience of his countrymen.” Please comment on the general mood of the country in response to this tragedy.

AG: Americans prided themselves, as citizens of a democracy, on the distance they enjoyed from monarchies; and monarchies were the places that told sad tales of the death of kings by assassination, murder, and poisoning. William Henry Seward even declared in 1862 that “assassination is not an American practice or habit, and one so vicious and so desperate engrafted into our political system.” He found out the hard way how wrong he was on the night of April 14, 1865. But it’s no wonder that the shock of Booth’s assassination plot, in murdering Lincoln and nearly killing Seward, hit Americans with more than just the force of bad news. It unsettled our understanding of ourselves as a democratic culture.

The assassination cut all the more deeply coming so hard on the heels of what everyone assumed was the collapse of the Confederacy and the end of the Civil War. The remembrances people left are so numerous and varied that they resemble a kind of photographic flash, a moment everyone recalls for where they were and what they were doing, a moment people felt compelled to record in diaries and letters. One of my favorite “flash” bulbs is in the diary of John Langdon Sibley, the librarian of Harvard College. Walking into Harvard Square (one of my old and favorite haunts) the morning of Lincoln’s death, “there was a deep feeling of thoughtfulness and sadness on every face & there were tears as people crowded round the post office, & the bulletin board at the room where newspapers were sold.”

Sibley found the “same feelings, in an intensified state” across the Charles River in Boston, where “places of business were rapidly closed & their fronts all along the main streets were draped in mourning…Where people congregated, speeches & in some places prayers were made.”

The same “flash” bulb went off elsewhere. Edward Neill, one of Lincoln’s White House staffers, was roused from sleep by a railroad crossing guard pounding on his door, who announced that “all travel on the road from Washington had been stopped, and then he burst into tears.”

Neill rode into Washington on the morning of April 15th “upon the tender of a locomotive” and found the streets around the White House crowded, but inside, “the halls of the mansion, ordinarily filled with visitors, were still, and everything seemed to weep.” Richard Lathers, a merchant who shuttled between New York City and South Carolina, was living in New Rochelle. He came down to New York City at once on April 15th, discovering that clerks at A.T. Stewart were already rationing the amount of black drapery – “bombazine” – customers could buy. Lathers advised anyone from the Southern states who was in New York City “to return to their hotels and lock themselves into their rooms for the day” for their own safety, since “a most respectable Northern commission merchant” who had unwisely said that “the South should not be held responsible for the acts of madmen and assassins” only “escaped with his life …by taking refuge in a cellar, whence he was able to get unperceived into a side street.”

The vast array of frenzied responses to the assassination has been dramatically reviewed in Martha Hodes’ Mourning Lincoln, in Richard Fox’s Lincoln’s Body, and Thomas Turner’s Beware the People Weeping, just to mention three (to which I’ll quickly add Lloyd Lewis, Ed Steers and David Chesebrough).

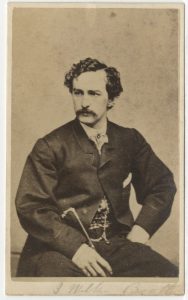

SG: Is there any evidence that Booth was cognizant of the fact that his plot was to take place on Good Friday…or was it simply a coincidence once he heard about the planned visit to Ford’s Theatre?

SG: Is there any evidence that Booth was cognizant of the fact that his plot was to take place on Good Friday…or was it simply a coincidence once he heard about the planned visit to Ford’s Theatre?

AG: Booth never showed much serious interest in religion, so while he was surely aware that April 14th was Good Friday (if only because everything buzzing around him in Washington would remind of that), Booth never showed any sign of connecting the day with his plot. Booth had been baptized an Episcopalian, and was wearing a small Catholic medal at the time of his death (which may have come from his sister, Asia, who was a convert to Catholicism). But Booth himself was described by one friend as a “free thinker,” so it’s not likely he attached any religious significance to the day he would kill the 16th president. The trigger for his deed was the discovery that morning that Lincoln would visit Ford’s that night for Laura Keene’s benefit performance, which for Booth was like the fly obligingly walking into his dramatic web.

SG: In reporting on the assassination, you mention several references connecting the Good Friday attack on Lincoln with the crucifixion of Jesus. You also point out some objections to this comparison. Please comment:

AG: Preachers who took to their pulpits that weekend were sometimes quick to draw a parallel between Jesus’ death on Good Friday and Lincoln’s assassination on that same day in the calendar. Laura Towne heard one freedman claim that “Lincoln died for we, Christ died for we, and me believe him de same mans.” That was, however, precisely the identification the preachers preferred to avoid, since it would have been blasphemous to have affirmed that Lincoln was a latter-day Christ. But some of them came pretty close.

Joseph Parrish Thompson, in a sermon in New York City, described Lincoln as a man of “grandeur” – “not greatness of endowment nor of achievement, but grandeur of soul. Grand in his simplicity and kindness; grand in his wisdom of resolve and his integrity of purpose; grand in his trust in principles and the principles he made his trust; grand in his devotion to truth, to duty, and to right; grand in his consecration to his country and to God…” One preacher in Buffalo, speaking extemporaneously, raised the rhetorical stakes still higher when he claimed that “Abraham Lincoln’s death by murder canonizes his life” and made “his words, his messages, his proclamations…the American Evangel.” Lincoln’s words now became “the political Gospel of our country, sealed with blood.”

However, it was more prudent for many preachers to make the comparison to Moses, dying just on the verge of entering the promised land. Just as “our Moses led the people through the wilderness to the borders of Canaan, and saw as from Mount Pisgah the glorious land of Promise, and laid him down to die,” so Dutch Reformed minister Ebenezer Platt Rogers, speaking at a mass meeting in New York’s Union Square, declared that God had taken this new Moses and sent “another Joshua” – Andrew Johnson – “to take his work upon him, and to clear this beautiful land of the last remnant of the rebellious tribes.”

Even so, Lincoln’s assassination in a theatre posed more than a little difficulty for the preachers, who had not lost their horror of theatres as the resorts of low-lifes and prostitutes, much less to have it take place on Good Friday, when a presumably pious president ought to have been spending time in church. “Would that he had fallen elsewhere than at the very gates of Hell – in the theatre,” complained George Duffield, the author of the antislavery hymn ‘Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus.’ “God grant that it may prove the brand of infamy consigning the theatre…to the disgrace it merits, and the abhorrence of this nation.”

There were even preachers who rebuked their congregations for worshipping Lincoln too much in life, and who were being taught in his death not to trust in human resources. “The people of this country are inclined to hero-worship,” one Troy, New York, Presbyterian preacher complained, “It may be on this account that our President has been taken from us. God is a jealous God and will not suffer the honor and glory that are due himself to be ascribed to any creature.”

I suppose that if I had to preach a sermon on the death of Lincoln, it would be less about Lincoln and more about my hearers. Why did God permit the murder of Lincoln? Wrong question. No, I tell you. Unless you repent, you will all likewise perish (Luke 13:3).

SG: Please report on William Herndon’s response to the assassination.

AG: Only four days before Lincoln’s assassination, Herndon had spoken at a mass celebration meeting in Springfield at the State Capitol building. There were parades – even Lincoln’s horse, ‘Old Bob,’ was one of the featured items – a 20-gun salute, and fireworks, and at eight in the evening, Jesse DuBois presided over an assembly in the Hall of Representatives where Herndon and four others gave speeches.

Then came the news of the assassination. Herndon felt Lincoln’s death with particular pain. Lincoln had trusted him and confided in him more than any other individual in Springfield, and now Lincoln was gone. He wrote to Caroline Dall a month later that “the news of his going struck me dumb, the deed being so infernally wicked – so monstrous – so huge in its consequences, that it was too large to enter my brain.” But not so dumb that he couldn’t manage a speech. Although Springfield itself “wore the appearance of deep gloom and sadness” and “a stillness almost oppressive reigned throughout the city.” Herndon was tagged on April 19th as one of the featured speakers, along with James Cook Conkling, at the First Baptist Church, where Herndon and Conkling “delivered most eloquent and interesting addresses…in the course of which many interesting reminiscences of the late Chief Magistrate were called up.”

Five days later, Herndon was the draftee of a series of resolutions for the members of the Springfield bar association, lauding Lincoln as “endeared to all who knew him by his uprightness, integrity, cordiality and kindness of heart, amenity of manner and his strict attention not only to the rights, but to the feelings of all…” Afterward, Herndon “made an appropriate, touching and eloquent address, in the course of which he alluded to his professional and social relations with Mr. Lincoln, and eulogized his public and private virtues.” After another week, Herndon was informing people that he was contemplating some sort of biography of Lincoln, and in many ways, that biography became the story of much of the rest of Herndon’s life.

SG: What new information did you find in preparing this second edition?

AG: I saw the second edition less as an opportunity to introduce new material as to correct some of those bloopers I described. The most obvious one, the making of which I still do not quite understand, concerned Lincoln’s famous reply to Horace Greeley’s “Prayer of Twenty Millions.” In 1999, I identified the venue for Lincoln’s reply as the Daily National Republican; it was actually the National Intelligencer that Lincoln choose to use as his mouthpiece for replying to Greeley, probably because the National Intelligencer was the capital’s ‘paper of record’ at that time and edited by the old-line Whig, W.W. Seaton.

Another point I missed entirely was the vote count in the Lincoln-Douglas senatorial contest of 1858 – although in this case, I was not so much making a mistake as relying on a common oversight. Since the 1858 election was not a direct election – people voted in November 1858 for state legislators, who then in turn voted for US senator the following January – it had long been common to turn to the vote tallies for the two state line offices which were up for direct election in November 1858, and use the vote for the Democratic and Republican candidates as a proxy for what the vote for Lincoln or Douglas would have been. The numbers for those two offices are usually cited from Greeley’s Tribune Almanac for 1859, as either 124,566 Republican for the state education superintendent’s race (against 122,413 for the Democratic candidate) or 125,430 (as opposed to 121,609 for the Democratic candidate) for the state treasurer’s race. Those are the statistics most usually cited in books that mention the Lincoln-Douglas contest. On that reasoning, the results of the 1858 campaign should have given a slight, but only a very slight edge, to Lincoln. That did not make the seven great debates look all that towering, after all.

Several years later, however, I went through the ballot records in the archives of the Illinois Secretary of State and tabulated the votes as they had been recorded, precinct-by-precinct, for the legislative candidates. The votes for state legislators were the real proxies for a direct popular vote for US Senator, so if there was a difference between that and the customary reference to the Tribune Almanac, that would mean something. And there sure was. If those state legislative races were the real proxies for a popular vote, Lincoln should have defeated Douglas decisively.

Counting all the votes cast in the state House districts, there were actually 366,983 ballots cast, of which 166,374 were for Democratic candidates and 190,468 for Republicans. That means that if those votes had been cast directly Lincoln or Douglas, Lincoln would have “won” 52 percent of those votes. Of the 99,482 votes in the twelve open state Senate races, 44,750 went to Democrats, but 53,784 went to Republicans, so that Lincoln would have “won” there with an overwhelming 54 percent of the vote. The problem, however, was that the Illinois state constitution gave a lopsided apportionment edge to the downstate Democratic legislative districts, so when the voting took place in the legislature in January, 1859, Douglas was declared the winner.

SG: Probably an unfair question, but do you wish to comment on your own perception of Abraham Lincoln’s faith?

AG: No, I don’t think it’s unfair at all. The facts are pretty straightforward: Lincoln never joined a church, never was baptized, never took communion, never made a profession of faith in any religion. He was certainly born in a religious home. But Lincoln himself never showed any indication of religious commitments. His step-mother, Sarah Bush Lincoln, told Herndon that her step-son “had no particular religion—didn’t think of that question at that time if he ever did.” From her, Lincoln “learned to read the Bible — study it & the stories in it and all that was moraly & affectionate in it.” But as a twenty-something in New Salem and Springfield, he gained a reputation for being a “skeptic” or an “infidel,” and if Samuel Hill’s account to Herndon is true, Lincoln even wrote a short essay, glorifying unbelief – which Hill prudently threw into the fire before people could use it to smear Lincoln’s reputation.

This indifference to religion began to soften through the 1840s and ‘50s, partly because it was doing him no political good to be known as an unbeliever, but partly because of the personal losses he began to suffer through the death of his second son and then his father. He began to speak of himself as a kind of seeker, trying to struggle his way through skeins of doubt and uncertainty. “Probably it is my lot to go on in a twilight, feeling and reasoning my way, through life, as questioning, doubting Thomas did,” Lincoln told Aminda Rogers Rankin. But it did not make him a churchgoer, and the pastor of the 2nd Presbyterian Church in Springfield complained that Lincoln generally spent Sundays reading newspapers.

The Civil War softened that indifference still more, as he struggled to make sense of how a cause so plainly just as that of the Union could be meeting with so much defeat and disgrace. By 1862, Lincoln began speaking in almost personal terms about his need for the help of God and his confidence that Divine Providence would bring the war and the emancipation of the slaves to a successful conclusion.

Nevertheless, he still declined joining a church. He spoke of God, but not of Jesus or any other religious figure. Orville Hickman Browning noticed that Lincoln frequently spent Sunday afternoons reading the Bible, but only as a man might relax while reading a good book; no one ever saw him pray, either before meals or anywhere else. In his last great speech, his Second Inaugural, he spoke as no other American president has ever spoken about God and God’s direction of human affairs. But he spoke only of God as a Judge, not in theological terms, as a Father, a Forgiver, a Redeemer.

Lincoln was, as Herndon remarked, a religious man, but it was a religion of his own making, not the religion of the Bible. This did not prevent a host of well-intentioned people from claiming, after Lincoln’s death, that he had been secretly baptized, that he had decided to join the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church just before his assassination, that he had made all kinds of private revelations about being converted. “It is said upon good authority,” insisted Joseph Parrish Thompson, in one of the post-mortem eulogies the preachers delivered about Lincoln, “that had he lived he would have made a public profession of his faith in Christ.” And Lincoln’s first full-length biographer, Josiah Gilbert Holland, featured a story in his 1866 The Life of Abraham Lincoln in which he claimed to have heard from Newton Bateman, the Illinois state superintendent of education, that proved that “Mr. Lincoln had, in his quiet way, found a path to the Christian stand-point – that he had found God, and rested on the eternal truth of God.” But there is no evidence that any of these stories has anything but wishful thinking behind them.

Allen Guelzo is Director of the James Madison Program Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship and the Senior Research Scholar in the Council of the Humanities at Princeton University.