A Seldom Seen “Emancipator”

As Perplexing as Ever, a Century and a Half Later

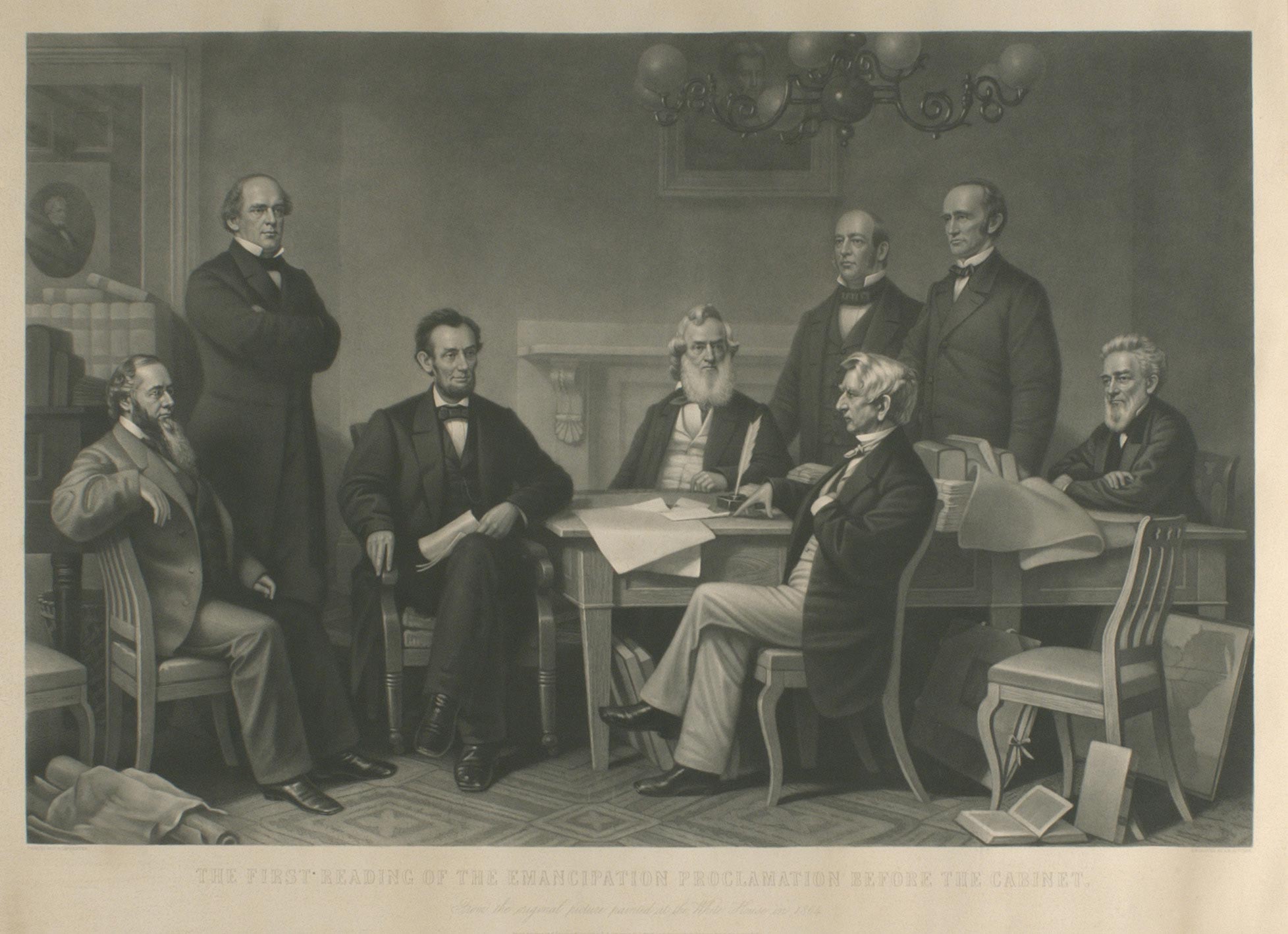

Few artists did more to cement the reigning nineteenth-century image of Abraham Lincoln as “Great Emancipator” than Francis B. Carpenter, whose monumental canvas, The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet, won critical acclaim on national tour beginning in 1864 and inspired an 1866 engraving that remained a best seller for decades. The print proved so ubiquitous and compelling that it stimulated rival printmakers to issue blatantly pirated variants, prints that similarly showed Lincoln reading his decree to his Cabinet ministers. Judging from the number of copies that survive in both institutional and private collections, such shamelessly plagiarized adaptations, by the likes of Edward Herline and Thomas Kelly, achieved significant popularity of their own.

The same cannot be said of a print based on a painting that was much more ambitious and considerably more original and that interpreted the “emancipation moment” from a far different perspective—focusing on its inspiration and composition rather than its mere announcement. The rarity of surviving copies, however, indicates that audiences of the day found something about this unique work of art unappealing—or perhaps unfathomable. Among the precious few surviving copies is a pristine chromolithograph in the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection at the Indiana State Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana.1

Believing his work “need borrow no inspiration from imaginary curtain or column,” Carpenter employed a “realistic” approach to his portrayal.2 He kept his composition simple and uncluttered, providing lifelike portraiture, a realistic setting (Lincoln’s office), and minimal and easy-to-parse symbolism (Carpenter chose respective left-and-right grouping of Cabinet liberals and conservatives). American audiences seldom understood, much less embraced, more complex “messages.”

That apparently did not discourage the Irish-Scottish painter David Gilmour Blythe (1815-1865). While still a teenaged immigrant in Pittsburgh, Blythe had begun studying art as an apprentice interior designer. In subsequent travels, he was exposed to the work of Boston artist David Claypoole Johnston (whose own son painted Abraham Lincoln from life in 1860), and seems to have embraced the elder Johnston’s humorous, complex, often grotesquely exaggerated style—part portraiture, part caricature. Through the 1840s and 1850s, Blythe himself evolved into a busy portrait and history painter, ever restless to experiment with new styles.3

Like many artists of his time, Blythe was gripped by the drama of the Civil War, although he seemed unable to develop a consistent way of depicting it. He produced a straightforward, panoramic landscape of General Doubleday Crossing the Potomac en route to Gettysburg, and also a hellish scene of human suffering in Libby Prison.4 Rejecting realism, he portrayed the president for the first time in Lincoln Crushing the Dragon of Rebellion, painted in 1862. In a symbol-laden, cartoon-like composition, Blythe portrayed a casually dressed president literally beating back a Copperhead monster with a club shaped like a Lincolnian log rail.5

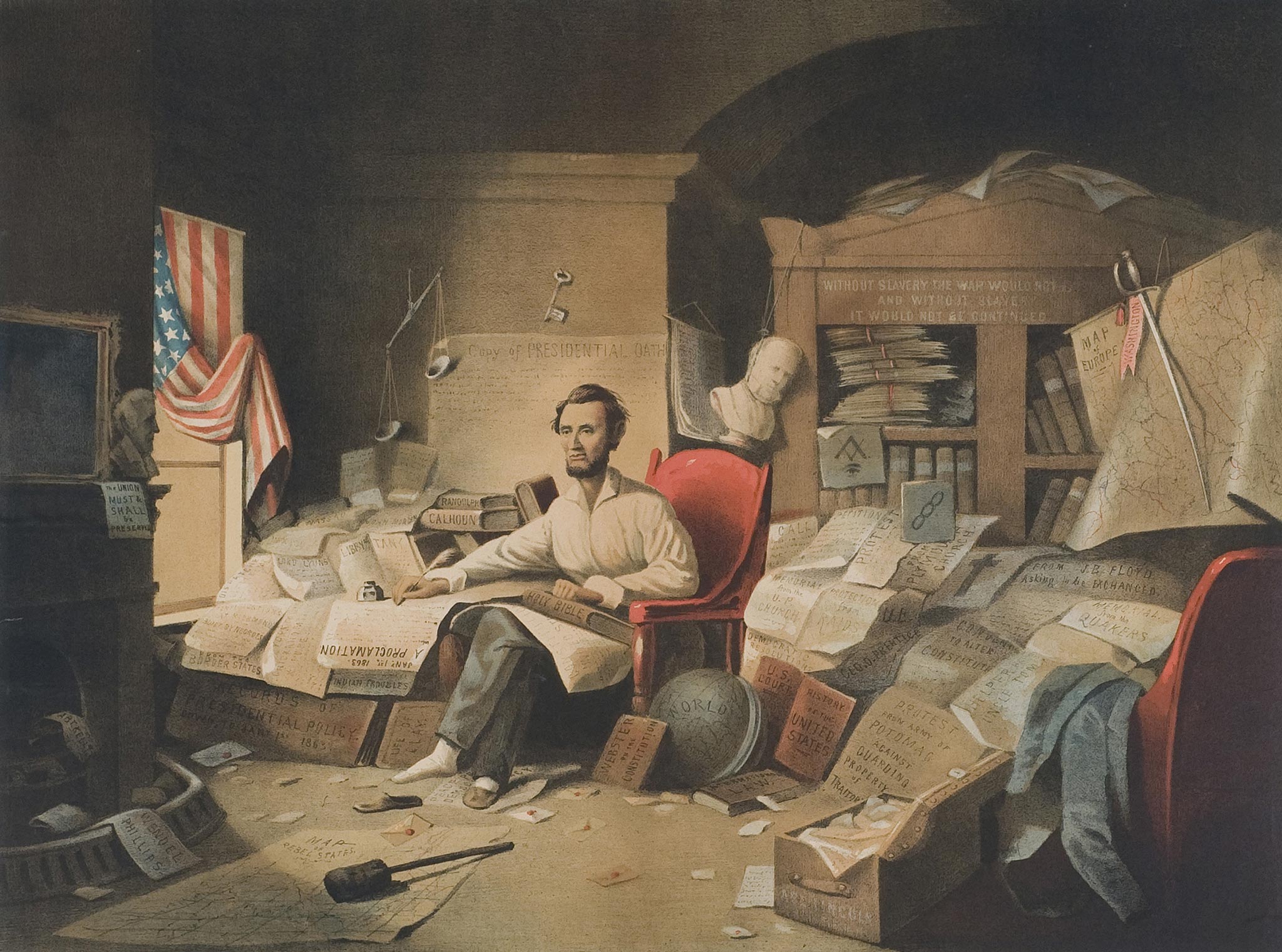

Blythe reached the apogee of his new, expressionistic style with the canvas Lincoln Writing the Proclamation of Freedom January 1, 1863. Here was the polar opposite of Carpenter’s subsequent, formally clad Great Emancipator. Blythe’s Lincoln, his face dark and downcast, his hair rumpled, was shown sitting in a cluttered office wearing an open white shirt and bedroom slippers, one of which has fallen off his foot. He balances the proclamation-in-progress on his lap atop a pile of books and documents, including the Bible and the Constitution. Everything strewn about the disordered room seems to suggest either the chaotic state of national war or the pressures facing the beleaguered Union leader—not to mention the unrestrained inventiveness of the painter.

Blythe made sure the details and decorations symbolized either Lincoln’s determination or challenges: a map of the Rebel states covered by a rail-splitter’s maul; another map, of South Carolina, provocatively kept in place by a cannonball; and a map of Europe (representing the dangerous potential for foreign intervention); a bust of Lincoln’s ineffective predecessor, President James Buchanan, hanging from a bookcase by its neck; and scales of justice to remind Lincoln that, in striking against slavery, he must balance his quest to restore the Union with a determination to respect the Constitution. A masonic symbol can be glimpsed as well—in this case attesting to the fact that the artist, not his subject, was a Mason.

American flags serve as patriotic decoration in the Blythe canvas: a copy of the presidential oath reminds Lincoln of his pledge to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution; and various religious and military tracts scattered about the floor suggest both inspiration and authority. Visible in the foreground is a battered old trunk bearing Lincoln’s name and Springfield hometown, perhaps to not only represent Lincoln’s humble origins, but to suggest the very real political danger of his imminent return to private life in Illinois should the emancipation policy backfire. This Emancipator is already packed to head home!

If Blythe’s painting was ever displayed anywhere, no record of its exhibition has ever been discovered. In fact, the canvas might have been entirely lost to history had it not been adapted a year after its creation by a Cincinnati lithographer, Ehrgott, Forbriger & Co., and published by M. Dupuy in Blythe’s Pittsburgh hometown. Yet this attempt to broaden its appeal failed—judging alone from the exceptional rarity of surviving copies. Its scarcity (compared to the abundance of surviving Carpenter prints) suggests that Blythe’s design, and the lithographer’s adaptation (he changed some details), elicited little notice or approval from picture-buying audiences of the Civil War era. This proved the case even though the lithographers made Lincoln a bit more recognizable by discarding Blythe’s rudely sketched likeness and substituting a slavishly copied Mathew Brady photograph—one that ironically had been posed by Carpenter himself as a model for his painting.

What do we make of Blythe’s failure? Was his canvas a miscalculation of interpretation and stylistic sensibility? Or was its failure attributable to market forces? For one thing, its obscurity certainly suggests that to secure popularity for an original image, it helped to have it copied expertly and mass-produced by a major publisher in a large Eastern city. Carpenter’s canvas was handsomely engraved in mezzotint by Alexander H. Ritchie and issued by Derby & Miller, a thriving New York publishing house that promoted it in all its other publications, including Carpenter’s own memoirs.

Blythe’s canvas, on the other hand, was reproduced in chromolithography—a hastier, more inexpensive, less prestigious medium than engraving. And while this meant that it was made available to purchasers more cheaply than the Carpenter adaptation (signed proof copies of which sold for $50), the firm of M. Dupuy of Pittsburgh could hardly match its rival’s distribution and promotion capabilities, even though the Blythe print did boast the added appeal of colorful tinting.

That said, some of the “blame” for the Blythe picture’s obscurity must rest squarely with the painter’s daring conception and frenzied style. Americans who supported the Proclamation in all likelihood preferred to celebrate it by displaying straightforward, easily comprehensible pictorial tributes that touted emancipation and honored the Emancipator as a statesman. Blythe’s canvas, its originality notwithstanding, made Lincoln’s efforts seem almost madcap. A print buyer contemplating its purchase might have been thoroughly confused by the cacophony of discordant symbolic devices crowding the scene, perhaps even somewhat offended by the sight of an unshod chief executive sitting in what appears to be his nightshirt amidst perplexing disarray that reminded viewers of his uncertainty when admirers may have preferred representations of his determination and authority. By attempting to reflect Lincoln’s anguish, perhaps accurately, David Gilmour Blythe sacrificed commercial success to his artistic and historical vision—and in the process relegated one of the most interesting of all emancipation images to obscurity.

It might be added that in print publishing, as in so many other fields of commercial endeavor, timing is invariably everything. The print adaptation of Francis Carpenter’s painting took years to produce, perhaps fortuitously. When it finally appeared, Lincoln had been dead (and sanctified) for a year, the amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery was law, and the late president’s most hotly controversial acts—like the Proclamation—had been reinterpreted in the forgiving afterglow of martyrdom. By contrast, Ehrgott, Forbriger published its Blythe print in the din of the 1864 presidential campaign, when emancipation remained a hotly debated and divisive issue and its author a highly controversial figure—to some, a tyrant. Whether an informally clad Lincoln ever experienced such uncertainty in pondering each word of what he later called “the great event of the nineteenth century,”6 Americans evidently preferred to remember him confidently reading the resulting text to his Cabinet members—and chose to celebrate the proclamation later, rather than sooner.

Harold Holzer is the Jonathan F. Fanton Director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College.

* * *

- See Lincoln Lore No. 1494 (August 1962), 2.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House with President Lincoln: The Story of a Picture (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1866), 25.

- Dorothy Miller, The Life and Work of David G. Blythe (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1950), 1, 2, 5, 9, 14.

- For the latter, see American Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2 vols. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1969) 1:39.

- Ibid., 57-58, 88-89.

- Frank Carpenter, “Anecdotes and Reminiscences,” in Henry J. Raymond, The Life and Public Services of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Derby & Miller, 1865), 764.