A Right Smart Get Out

A Right Smart Get Out by M. Kelly Tillery

It is difficult to imagine, much less fully appreciate, that in June of 1864 the democratic republic as a form of government was extremely rare and under siege. This nation was the only large democracy, other than Britain, though that nation restricted the vote to less than 5% of its citizenry and had a monarch and one hereditary house of its legislature. The tiny Swiss Republic, the Republic of San Marino, Liberia and the Boer Republics in South Africa were the only other democracies in a world otherwise governed by dictators, dynasties, warlords, and a wide variety of so-called “royals.”

This nation and its special form of government, “of the people, by the people and for the people” was still an experiment, and, sadly, one then in serious danger of failing.

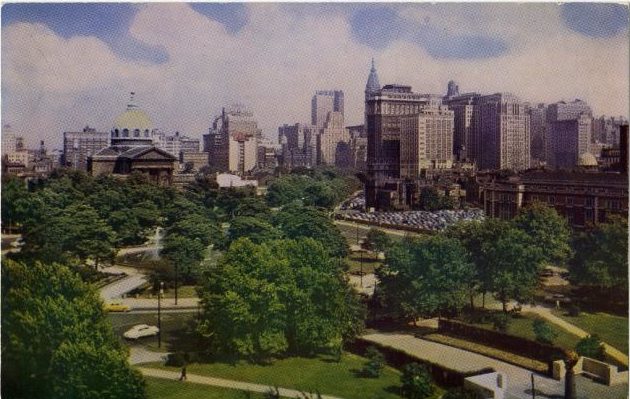

Come with me now, for a moment back in time to June 16, 1864, Logan Square, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

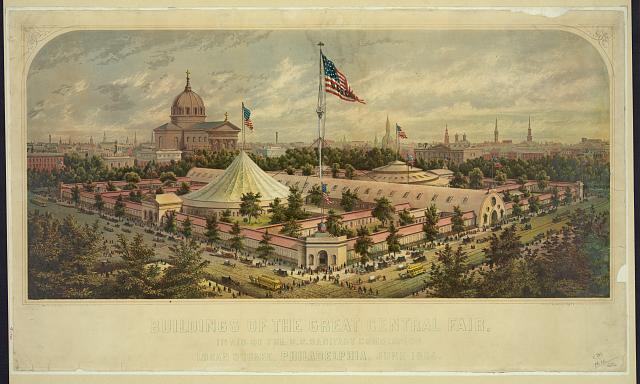

President Lincoln had approved the U.S. Sanitary Commission as an official, though voluntary, organization in 1861, to provide comfort and relief to the troops. The Philadelphia Branch, in conjunction with the New Jersey and Delaware Branches and with support from The Union League, sponsored a Great Central Fair on June 7-28, 1864 in Philadelphia on Logan Square, a fundraising event that raised over $1,000,000 the equivalent of almost $15,000,000 today.

Although invited to attend the opening ceremonies on June 7th , Lincoln declined, but then agreed to attend on the 16th.

The greatest orator of the day, Edward Everett, was also set to speak. Lincoln had shared the podium with Everett, seven months before at Gettysburg. There, on November 19, 1863, Everett spoke first, for two hours; Lincoln spoke next, for two minutes.

The Fair organizers thought it best that the President speak first – and he did. Everett knew it best, too. The day after the Gettysburg ceremony, Everett humbly had written to Lincoln, “… if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

Although in the midst of a campaign for re-election, and one that he then fully expected to lose, Lincoln, the politician/statesman, consciously chose not to use this visit to make political speeches. At a banquet in the Main Assembly Hall, laid out across Logan Square, at about 7 P.M., Lincoln gave a brief speech commending the fine work of this private, volunteer organization in giving comfort and relief to Union soldiers.

Impressed with Philadelphia’s effort on his behalf, the President was overheard to whisper, in his inimitable folksy way, that this was “a right smart get out.”

As he spoke, however, the war dragged on. While General Meade had driven Lee from Pennsylvania the summer before, over 100,000 men under Grant were then engaged in a fierce battle outside of Petersburg, Virginia, 270 miles away just south of Richmond. The Army of the Potomac was attacking the Army of Northern Virginia in a bloody battle that would start the ten-month Siege of Petersburg.

The war was far from over and Union victory was not yet certain. Less than a month later, Confederate troops under General Jubal Early came to within five miles of the Executive Mansion, the closest hostile troops had come since the British burned it in 1814.

In 1864 Philadelphia, the host city, had a population of 600,000. It was the second largest city in the United States and fourth largest in the Western world.

Temple University’s Dr. Anthony Waskie called Philadelphia, in his wonderful book of the same name, the “Arsenal of The Union.” It had over 6,300 manufactories, two major arsenals, a navy yard, and scores of armories.

Philadelphia was also the largest center for medical care in the nation, if not the world at the time – 24 military hospitals and scores of branches. Over 157,000 Union soldiers received medical treatment in the City during the war, most of whom were aided in some way by the Commission.

A review of the Final Report of the U.S. Sanitary Commission Philadelphia Chapter reveals that the ladies of the Commission provided, as one might expect, substantial food and medical supplies. They also provided “comfort” to the troops, which included supplying a considerable amount of alcohol and tobacco. And, inexplicably, an inordinate amount of combs and handkerchiefs. Apparently, even back then, looking good was as important as feeling good.

Professor Waskie has observed that the Commission “was probably the greatest purely civic act of voluntary benevolence ever attempted in Philadelphia.” That is, I suppose, until LIVE AID, 121 years later.

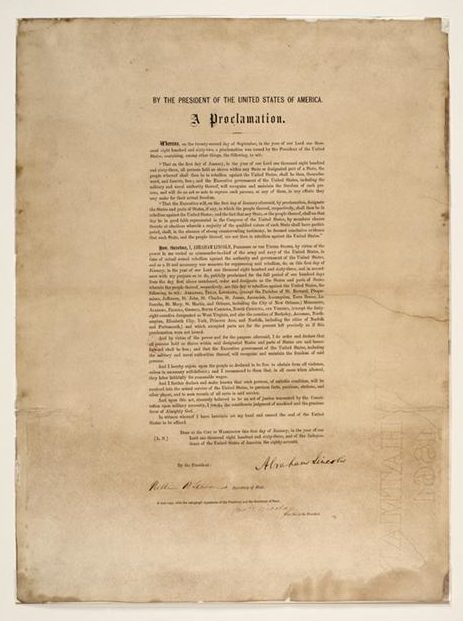

President Lincoln had approved, by Executive Order, the Commission almost precisely three years before on June 9, 1861. He did so reluctantly, however, concerned that, as he said, “it might become a fifth wheel to the coach.” His Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton detested the Commission as being meddlesome in military affairs. But, as part of Lincoln’s genius was his ability to learn from experience and accordingly adapt his views and policies, he came to appreciate the substantial value of the Commission to the Union cause. He knew that five men died of disease for every two killed by wounds and thus more sanitary conditions amongst the Union’s forces might ensure its survival.

While we remember the Sanitary Commission for the incredible work of the thousands of women volunteers who did the hard day to day work of aid and comfort to the Union soldiers, it is well to note that (and perhaps this was a sign of the times) every one of the Commission members, officers, executives and committee members was a man.

The male Commission members actually frowned upon these local fairs thinking they supported local branches at the expense of the national organization. But when the Commission men tried to hold their own fair in New York, City, it was a failure by comparison to others.

Though claiming, somewhat in jest, not to understand them, Lincoln had always supported and appreciated the women of America. He had supported giving them the vote as early as 1836, 84 years before they got it.

Not three months before at a similar fair in Washington, he had concluded his remarks, praising the role of women in alleviating soldiers’ suffering, saying, “God Bless the women of America!”

Kelly Tillery practices law at Pepper Hamilton in Philadelphia.