A New Lincoln Discovery

A New Lincoln Discovery: Family of Lincoln Enthusiast Finds Unprecedented Autograph Collection & Lincoln-Related Items

Jason Emerson

Some new Lincoln relics have surfaced recently, owned by the family of a man who had met and “known” Abraham Lincoln and had spent decades traveling the world talking about the Great Emancipator. While today we all carry cell phones in our pockets and record life in selfies, this man, Rev. Francis D. Blakeslee, traveled through his later life with an autograph book in his pocket, and met some of the most important and fascinating people of his generation. His book contains not only Abraham Lincoln’s signature (and five other US presidents), but also a number of signatures connected to the Lincoln family, the Civil War, and the 1865 assassination. A second book owned by Blakeslee describes how he acquired many of the autographs, a Lincoln-signed envelope, and a unique 1860 Republican Party Lincoln badge. Blakeslee also left for posterity numerous written recollections of his meetings with and sightings of the great Civil War president, including one experience that historians have since used to verify Lincoln’s location on the afternoon of his assassination. Like most such discoveries of previously unseen historical artifacts, Blakeslee’s family had these items in their possession but only found them about 10 years ago, and did not really understand the importance of what they had. Nobody outside their family has seen the artifacts since probably the 1930s.

Who was Francis Blakeslee?

Blakeslee was known for much of his life as a national authority on Abraham Lincoln. He spoke across the country and around the world on Lincoln, wrote two booklets and numerous articles, and was labeled during his life as one of the last people to see Abraham Lincoln alive on the day of his assassination. “I probably have had more contacts with Mr. Lincoln than any man living,” Blakeslee said in 1939.[1]

Francis Durbin Blakeslee was born Feb. 1, 1846, in Vestal, N.Y. During the Civil War, being too young to enlist without his parents’ permission, he was quartermaster’s clerk in the 50th New York engineers in Rappahannock Station, Va., in 1863-64, and a clerk in the quartermaster-general’s office at Washington, D.C. in 1864-65. After the war, he got married and had three children. He became an ordained Methodist Episcopal minister in 1870. Blakeslee served in numerous positions as educator, administrator, and pastor throughout his life; he was also an ardent temperance advocate, and served many years as superintendent of the Binghamton, NY chapter of the Anti-Saloon League.

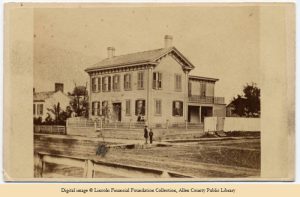

During his life, Blakeslee traveled the world — and lectured as he went. During his early years, his main topic was prohibition and the evils of alcohol. Starting in the 1920s, Blakeslee’s lectures began to mix his views on temperance with his belief in Abraham Lincoln’s disdain of liquor. Finally, his lectures came to focus solely on his personal recollections of Abraham Lincoln and his belief in the Great Emancipator’s historical worth. Blakeslee was also an inveterate writer. He contributed articles to newspapers across the U.S. in which he detailed his national and world travels as well as his connections to Abraham Lincoln. In the 1920s, after he moved to California from Binghamton, he wrote articles about numerous subjects, including a detailed description of his visit to Lincoln’s Home in Illinois and his personal recollections of Abraham Lincoln.[2]

During his life, Blakeslee traveled the world — and lectured as he went. During his early years, his main topic was prohibition and the evils of alcohol. Starting in the 1920s, Blakeslee’s lectures began to mix his views on temperance with his belief in Abraham Lincoln’s disdain of liquor. Finally, his lectures came to focus solely on his personal recollections of Abraham Lincoln and his belief in the Great Emancipator’s historical worth. Blakeslee was also an inveterate writer. He contributed articles to newspapers across the U.S. in which he detailed his national and world travels as well as his connections to Abraham Lincoln. In the 1920s, after he moved to California from Binghamton, he wrote articles about numerous subjects, including a detailed description of his visit to Lincoln’s Home in Illinois and his personal recollections of Abraham Lincoln.[2]

Blakeslee and Lincoln

While a clerk in the War Department in 1864-65, Blakeslee saw Lincoln often, as the president was a regular visitor. But mostly, the 18-year-old clerk saw Lincoln at public functions and in public places. He saw the president sometimes at the theater, outside the White House, at church, and at public events while Lincoln gave speeches. “While engaged in my position as a clerk in the Quartermaster General’s Office, I had many excellent opportunities of seeing Lincoln, and in fact I had often met him,” Blakeslee wrote in 1909.[3]

But certain moments stood out to Blakeslee, and these he spoke of often in his Lincoln talks. One such moment was how his father, Rev. George H. Blakeslee, a Methodist minister from Binghamton, met the president and obtained his autograph.[4] The senior Blakeslee was on leave from his pastoral duties in response to a call from the U.S. Christian Commission asking all men of the cloth to go to the front and minister to soldiers on the battlefields and in the hospitals, and to hold religious services among the troops. George did this from Oct. 4 to Nov. 4 and, stopping in Washington on his way home from the battlefields to visit his son Francis, decided to call upon the president at the White House.

According to the elder Blakeslee’s dairy, he watched the president interact with a number of people — and his reactions are not what modern-day people would expect of the historic figure who is typically characterized as almost Christ-like in his kindness and forgiveness:

“Four young men approached the president who were anxious to get his aid relative to a matter which I

did not understand. But Mr. Lincoln, who was seated in his chair, replied to them kindly but firmly, ‘I can do nothing for you.’ When they urged that their papers should be read, he replied, ‘I should not remember if I did. The papers can be put into their proper places and go through their proper channels.’A lady next appeared and presented a paper. He took it out and read it and replied, ‘This will not do. I can do nothing for your husband.’ ‘Why not?’ said the lady. ‘Because,’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘he is not loyal.’ ‘But he intends to be; he wants to take the oath of allegiance.’ ‘That is the way with all who get into prison,’ replied the President. ‘I can do nothing for you.’ ‘But you would,’ said the lady,’ if you knew my circumstances.’ ‘No, I would not. I am under no obligation to provide for the wives of disloyal husbands.'”[5]

After watching Lincoln’s interactions, George Blakeslee and his companion, Rev. E.W. Breckinridge (no relation to John C. Breckinridge, one of the four candidates for President in 1860, which the reverend told Lincoln when they met), watched Lincoln dispatch another widow in the same way, then shook hands with the president, and Blakeslee asked for the president’s signature. Lincoln “cheerfully” gave his autograph “For G.H. Blakeslee” in a memorandum book of the Christian Commission, given to George as one of the delegates of that service.

“I treasure as prized possessions the leather-bound book which contains the autograph inscription in Lincoln’s own hand, and my father’s diary relating how he secured this precious memento that memorable day,” Francis wrote in 1927.[6] In a later newspaper article he stated, “The ink is as black as the day it was written.”[7] Francis also saw the president as an official visitor himself on Jan. 2, 1865, with two women from his boarding house. “Shook his paw with gusto,” Francis wrote in his diary.[8]

Three months after meeting the president, Blakeslee was present for what would become Lincoln’s last two public addresses before his death, which he delivered from a second-story window of the White House on April 10 and 11, 1865 shortly after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered his army to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9.

In the April 10 speech, Lincoln responded to calls for impromptu remarks by declining, and promising he would speak the next day. The April 11 speech was “long and formal,” read from a written draft, and delivered to “an immense throng of people, who with bands, banners, and loud huzzahs, poured into the semi-circular avenue in front of the Executive Mansion,” wrote reporter Noah Brooks.[9] Lincoln’s remarks that night focused on the topic of Reconstruction, especially as it related to the state of Louisiana. Within that speech, Lincoln expressed his support for black suffrage for the first time in public. Francis Blakeslee was at the White House and part of the immense crowds cheering Lincoln at the successful conclusion of the war. In his diary that night, Blakeslee’s anticlimactic description of that momentous April 11 speech simply stated, “It was about 20 minutes long and related to the problems confronting the nation at that crisis of its history, and may be found today among his published writings.”[10]

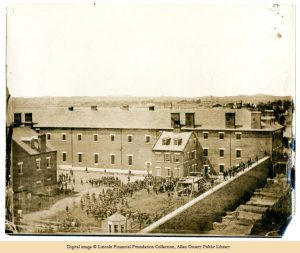

Blakeslee also saw Lincoln on the afternoon of April 14, 1865 — the day the president was assassinated. Blakeslee and a few of his friends had gone to the Navy Yard to admire the ironclad ships damaged in the battle at Fort Fisher, and which were docked for repairs. As the friends stood on a platform in the Yard, the president and Mrs. Lincoln drove up in their carriage and stopped at the opposite end of the platform. “We saluted, and the salute was returned,” Blakeslee wrote.[11] He also told a correspondent in 1910 that it was between 5 and 6 o’clock that day that he saw the Lincolns at the Navy Yard. “He and Mrs. Lincoln came there in their carriage on their afternoon drive. They came within a rod or two of where I was and I saluted him,” Blakeslee wrote.[12]

Blakeslee also saw Lincoln on the afternoon of April 14, 1865 — the day the president was assassinated. Blakeslee and a few of his friends had gone to the Navy Yard to admire the ironclad ships damaged in the battle at Fort Fisher, and which were docked for repairs. As the friends stood on a platform in the Yard, the president and Mrs. Lincoln drove up in their carriage and stopped at the opposite end of the platform. “We saluted, and the salute was returned,” Blakeslee wrote.[11] He also told a correspondent in 1910 that it was between 5 and 6 o’clock that day that he saw the Lincolns at the Navy Yard. “He and Mrs. Lincoln came there in their carriage on their afternoon drive. They came within a rod or two of where I was and I saluted him,” Blakeslee wrote.[12]

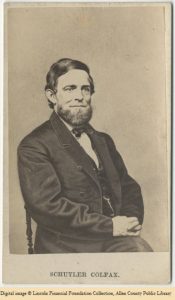

Blakeslee recounted that in later years he met former Speaker of the House and former Vice President Schuyler Colfax following one of Colfax’s lectures on Lincoln. “Mr. Colfax told me that he knew for a fact that I saw the great man later than did any of his Cabinet. He said to me, ‘I know where they all were that day and evening, and not one of them saw Mr. Lincoln as late as you did.’ No credit to me; only one of the accidents or incidents of my early manhood. ‘But I am ahead of you,’ he continued; ‘I was talking with him at the White House when he entered the carriage to go to the theater.’”[13]

Blakeslee recounted that in later years he met former Speaker of the House and former Vice President Schuyler Colfax following one of Colfax’s lectures on Lincoln. “Mr. Colfax told me that he knew for a fact that I saw the great man later than did any of his Cabinet. He said to me, ‘I know where they all were that day and evening, and not one of them saw Mr. Lincoln as late as you did.’ No credit to me; only one of the accidents or incidents of my early manhood. ‘But I am ahead of you,’ he continued; ‘I was talking with him at the White House when he entered the carriage to go to the theater.’”[13]

Decades later, Blakeslee was told by Lincoln scholars that the “disputed question” of where the Lincolns actually took their final carriage ride on that fateful day seemed to hinge on his own testimony, with nobody apparently knowing that they even went to the Navy Yard until Blakeslee made it known. His story is recounted — either by quoting his 27-page monograph, “Personal Recollections and Impressions of Abraham Lincoln,” or by his correspondence — by Lincoln scholars John W. Starr (New Light on Lincoln’s Last Day, 1926), Rufus Rockwell Wilson (Intimate Memories of Lincoln, 1945) and W. Emerson Reck (A. Lincoln His Last 24 hours, 1987).[14]

That night, April 14, 1865, Blakeslee went to bed early in his lodging just down the street from Ford’s Theatre. Despite the noise and crowds out on the street that night after the president had been shot and lay dying in a boarding house on 14th Street, Blakeslee slept through the entire event. The next morning, he went to his usual restaurant for breakfast and noticed it was unusually quiet. “While the waitress was filling my order, the only other man at my table turned his daily papers — and then I read the black headlines telling me of the awful event of the night before,” he wrote in his diary. “My father, living hundreds of miles away … knew of the tragedy before I did.”[15]

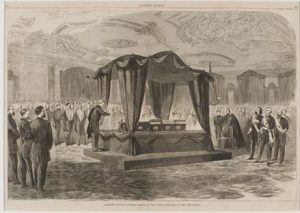

While Lincoln’s body lay in state in the White House, Blakeslee stood in line for hours and eventually got in. He stood by the casket and “looked into the cold face of him whom I had saluted in life a few hours previously.” As a civil servant, Blakeslee also watched and participated in the grand funeral procession of the president’s remains down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House to the Capitol on April 19.[16] He also spent two days attending the military trial of the assassination conspirators on the third floor of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary (nowadays on the grounds of Fort Lesley J. McNair). Blakeslee also met, on May 2, 1865 — six days after Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth was killed by Union troops — Boston Corbett, the soldier who killed the actor. Blakeslee said he was at a regular class meeting at McKendree Chapel (Now McKendree United Methodist Church, on Lawrence Street NE in Washington, DC) when he noticed a stranger present, who turned out to be Corbett. “I had a chat with him, got his autograph. He told me what I never saw in print, that the gun with which he shot Booth and for which he had been offered over $1,000, when he went to get it to loan to the Sanitary Commission Fair at Chicago, it was stolen,” Blakeslee wrote.[17]

While Lincoln’s body lay in state in the White House, Blakeslee stood in line for hours and eventually got in. He stood by the casket and “looked into the cold face of him whom I had saluted in life a few hours previously.” As a civil servant, Blakeslee also watched and participated in the grand funeral procession of the president’s remains down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House to the Capitol on April 19.[16] He also spent two days attending the military trial of the assassination conspirators on the third floor of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary (nowadays on the grounds of Fort Lesley J. McNair). Blakeslee also met, on May 2, 1865 — six days after Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth was killed by Union troops — Boston Corbett, the soldier who killed the actor. Blakeslee said he was at a regular class meeting at McKendree Chapel (Now McKendree United Methodist Church, on Lawrence Street NE in Washington, DC) when he noticed a stranger present, who turned out to be Corbett. “I had a chat with him, got his autograph. He told me what I never saw in print, that the gun with which he shot Booth and for which he had been offered over $1,000, when he went to get it to loan to the Sanitary Commission Fair at Chicago, it was stolen,” Blakeslee wrote.[17]

Coincidentally, more than 30 years later, Blakeslee serendipitously met more people with direct connections to Abraham Lincoln, including his only surviving son, Robert. When Blakeslee became president of Iowa Wesleyan University in 1898, the president of the board that elected him (and the university’s former president), was former U.S. Senator James Harlan, who had been a personal friend of President Lincoln and had been named a cabinet member shortly before the assassination. Harlan was also the father-in-law of Robert T. Lincoln, the oldest and only surviving son of Abraham and Mary Lincoln. When Harlan died in 1899, Blakeslee spoke at the funeral in the college chapel. During the funeral, he met Robert Lincoln and his wife, Mary Harlan Lincoln and, a few years later, interviewed Robert in Chicago when Lincoln was president of the Pullman Car Company.[18]

Blakeslee’s autograph collection

Francis Blakeslee’s autograph book, as mentioned above, was an 1864 memorandum book given to his father, George H. Blakeslee, as a member of the U.S. Christian Commission.[19] George started the practice of obtaining autographs in the book not with President Lincoln, but with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, whose signature — along with the signatures of 11 members of his senior staff: Brig Gen. John A. Rawlins, Gen. O.E Babcock, Lt. Col. Theodore S. Bowers, Lt. Col. E.S. Parker; Lt. Col. W.S. Duff; Lt. Col. M.R. Morgan, Lt. Col. Cyrus B. Comstock, Lt. Col. Adam Badeau, Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls, Gen. John C. Barnard, and Lt. J.H. Oberteuffer, Jr. — George obtained during his time in the field when he stopped at Union headquarters in City Point, Va.

While the autograph book — about 5×7 in size, rebound in the 1930s in black leather, but with worn, browned pages — contains signatures of people from all walks of life from across the globe, there is a certain Lincoln-centric aspect to it. In addition to Lincoln and Grant, autographs Blakeslee obtained include poets Edwin Markham (Oct. 13, 1913) and Carl Sandburg (January 1937), both of whom wrote about Abraham Lincoln, and E.J. Edward, the daughter of the sister of Col. E. D. Baker, one of Lincoln’s close friends. There are also Lincoln-related signatures that should be in Blakeslee’s book, but are not. In his many writings, Blakeslee said he obtained the autographs of James Harlan and Boston Corbett, but neither is in there. Blakeslee never said he got Robert Lincoln’s autograph, but it seems highly unlikely that he would have met Lincoln’s son at least twice and never asked for his signature. However, Robert’s signature is also not in Blakeslee’s book.

Perhaps the most amazing set of names that should be in the memo book but are not are the members of the nine-member military tribunal that tried the Lincoln assassination conspirators in May-June 1865. In his writings, Blakeslee said he attended two days of the assassins’ trial and, while there, he obtained the autographs of every judge by passing his autograph book across the bar. Again, those signatures are not in the book. A Binghamton newspaper, recording an interview with Blakeslee in April 1909 for the centennial of Lincoln’s birth, mentioned Blakeslee’s securing of the assassination trial judges’ signatures and called it, “what is considered to be one of the most valuable mementoes in the United States.” The article stated, “It is doubtful if there is a duplicate of this collection in the country, and needless to say Dr. Blakeslee prizes it highly. In the same collection is a signature of Lincoln which was secured not a great while before the assassination.”[20]

Perhaps the most amazing set of names that should be in the memo book but are not are the members of the nine-member military tribunal that tried the Lincoln assassination conspirators in May-June 1865. In his writings, Blakeslee said he attended two days of the assassins’ trial and, while there, he obtained the autographs of every judge by passing his autograph book across the bar. Again, those signatures are not in the book. A Binghamton newspaper, recording an interview with Blakeslee in April 1909 for the centennial of Lincoln’s birth, mentioned Blakeslee’s securing of the assassination trial judges’ signatures and called it, “what is considered to be one of the most valuable mementoes in the United States.” The article stated, “It is doubtful if there is a duplicate of this collection in the country, and needless to say Dr. Blakeslee prizes it highly. In the same collection is a signature of Lincoln which was secured not a great while before the assassination.”[20]

Why none of these autographs are in Blakeslee’s book, although they should be, is unknown. However, there are four pages in the book that have been neatly excised. It is logical to conclude that the signatures were on those pages and Blakeslee, or maybe one of his descendants, at some point cut them out. Blakeslee’s current living relatives have no idea about the missing pages.

Blakeslee often referred to his autograph book in his Lincoln lectures, and more than once he pulled the book out of his pocket to regale his audience with the book that Lincoln signed. In August 1934, the Poughkeepsie Eagle-News mentioned Blakeslee’s autograph book, starting with the news that the Los Angeles-based man had brought his book to the city and, while there, taken it to a local bindery for repairs. “A little black memorandum book has been handled gingerly these past two days at the Glendon Bates book bindery company. So highly is it regarded that it has reposed for the greater part of 48 hours in a huge fire-proof safe,” the article stated. “The yellowish, almost brittle pages saw the light yesterday when the press representative of a neighboring summer theater saw in it the value of a drama ‘news story.’ It contained drama of the past, but its interest may be even greater in the future.”

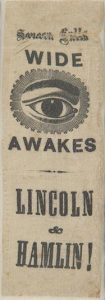

The article also describes as “probably the most interesting bit of Lincoln memorabilia” in the book is the 1860 Wide Awake Lincoln-Hamlin campaign ribbon, which is tucked in a clear folder inside the front cover. Blakeslee told the reporter that the badge may have been worn at the Republican nominating convention in 1860.[21] Blakeslee wrote in one of his articles that he spent decades researching the 1860 Wide Awake campaign ribbon and never found another like it, nor anyone who had ever seen or heard of a similar ribbon. He believed his ribbon may be the only one of its kind in existence. “I have been investigating it for 15 years,” he wrote in 1936, “holding it up before G.A.R. posts, and other audiences asking for a duplicate, without avail. The four great collections of Lincolniana haven’t it. Those badges and buttons of such organizations are almost never preserved. How this one came to be saved I cannot tell.”[22] James Cornelius, former Lincoln curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Ill., said the campaign ribbon is “highly unusual” and one that he has never seen before — although there is no way to say if it is indeed one-of-a-kind.[23]

The article also describes as “probably the most interesting bit of Lincoln memorabilia” in the book is the 1860 Wide Awake Lincoln-Hamlin campaign ribbon, which is tucked in a clear folder inside the front cover. Blakeslee told the reporter that the badge may have been worn at the Republican nominating convention in 1860.[21] Blakeslee wrote in one of his articles that he spent decades researching the 1860 Wide Awake campaign ribbon and never found another like it, nor anyone who had ever seen or heard of a similar ribbon. He believed his ribbon may be the only one of its kind in existence. “I have been investigating it for 15 years,” he wrote in 1936, “holding it up before G.A.R. posts, and other audiences asking for a duplicate, without avail. The four great collections of Lincolniana haven’t it. Those badges and buttons of such organizations are almost never preserved. How this one came to be saved I cannot tell.”[22] James Cornelius, former Lincoln curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Ill., said the campaign ribbon is “highly unusual” and one that he has never seen before — although there is no way to say if it is indeed one-of-a-kind.[23]

In addition to the Lincoln-related signatures that are (or are supposed to be) in the Blakeslee autograph book, there are numerous others from different years and numerous places around the world. The approximately 50 pages of autographs in Blakeslee’s book contain the names of many famous world characters. The presidents in the book include not only Lincoln and Grant (although Grant’s signature was obtained before he was president) but also William Howard Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Other American political names in the book include U.S. Senator Hiram Johnson and 19th century U.S. Senators Daniel Webster, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. There are also world leaders, soldiers, scientists, explorers, and entertainers.

Blakeslee also created a second, hand-written book in which he described the circumstances in which he obtained some of these signatures. His description of meeting Taft is interesting in that he stated that he told the former president, “I have with me tonight the autograph of Abraham Lincoln and I want to couple you on with Abraham Lincoln.” As I extended my fountain pen and the autograph album. “I should be most happy,” was his reply and he proceeded to write his name. Blakeslee also intrigued Theodore Roosevelt and got his signature in the book in a similar way. A Blakeslee associate called on the former president at his home in Oyster Bay, N.Y., a few months before Roosevelt’s death. Blakeslee said that Roosevelt, an ardent Lincoln admirer, was “more interested in the [1860 campaign] badge than in anything else in the book. I believe that he had never seen one like it.”[24]

The Blakeslee family artifacts

Blakeslee’s autograph book and accompanying artifacts have been in his family’s possession since the 1860s — or more than 150 years. Francis stated more than once that he found his father’s memo book and personal diary in the attic after George’s death. Apparently, Francis’ children likewise kept all his items. His great-grandchildren found the Blakeslee autograph book on a bookshelf in the Blakeslee family home about ten years ago and, when they were cleaning the house out after their grandparents’ death, they made sure to take the book with them.

In addition to Francis Blakeslee’s autograph books and Lincoln campaign badge, another family member owns additional historic family heirlooms, including a photograph of Abraham Lincoln that once belonged to her great-great grandfather Francis. The photo is mounted in a frame along with an envelope addressed to R.S. Thomas, Esq., with return address signed by A. Lincoln. There is no visible date, postal stamp, or address visible on the envelope, as it has faded from decades of exposure to sunlight. Richard Symmes Thomas was a lawyer in Virginia, Illinois, and an active Whig. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln show that Lincoln wrote to Thomas in the 1840s and early 1850s, including when Lincoln was a member of Congress in 1847-49.

Blakeslee’s final years

Francis Blakeslee was a prolific writer, speaker and traveler. After moving with his wife to California in the 1920s, Blakeslee criss-crossed the country preaching, and speaking about prohibitionism and Abraham Lincoln. It was in the 1920s that Blakeslee printed his two Lincoln-related pamphlets, and during that decade and the next he continually submitted articles to newspapers across the country. By the 1930s and early 1940s, Blakeslee was known nationwide not only as a Lincoln scholar and lecturer, but as the oldest living person to have met Abraham Lincoln, shaken his hand, heard him speak, seen the funeral, and more. When Blakeslee died in 1942 at age 96, the news was carried in numerous newspapers across the U.S. “Another chapter in American history closed yesterday with the death of Dr. Francis Durbin Blakeslee, 96, believed to be the last remaining person to have seen Abraham Lincoln the day he was assassinated,” stated the Los Angeles Times.[25]

Perhaps the best look at Blakeslee was printed in February 1942, seven months before he passed away, in the Los Angeles Times. The article shows Blakeslee, despite his advanced age, living his life as he always did. It described him “seated in his easy chair writing an essay on ‘My Memories of Lincoln.’ Dr. Blakeslee, who has given hundreds of lectures on Lincoln, no longer is able to give public addresses, but he continues to write his memoirs of the statesman.”[26] That night, Blakeslee was honored at a Syracuse University Alumni of Southern California dinner, after which he attended — you guessed it — a lecture on Abraham Lincoln.

Jason Emerson is the author of The Madness of Mary Lincoln and Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert Todd Lincoln.

(Portions of this article were published in the book co-authored with Erica Barnes: “The Bear Tree” and Other Stories from Cazenovia’s History.)

[1] “Ex-Cazenovia Seminary Head Still Excels as Wood Cutter,” Cazenovia Republican, April 6, 1939, 1.

[2] These articles were printed in newspapers across the U.S., particularly those published in towns in which Blakeslee previously or currently lived, such as Cazenovia, N.Y., Potsdam, N.Y., Binghamton, N.Y., Penn Yan, N.Y., and Los Angeles, California.

[3] “Talked to Lincoln Later than Cabinet officers,” Cazenovia Republican, April 22, 1909, 1. This article reprints the Binghamton newspapers article. Francis Durbin Blakeslee, Personal Recollections and Impressions of Abraham Lincoln (Gardena, Calif: Spanish American Institute Press, 1927).

[4] Blakeslee tells the complete story in his booklet, How My Father Secured Lincoln’s Autograph, privately printed: Spanish American Institute Press, 1927. See also Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 11-12; F.D. Blakeslee, “Lincoln As I Knew Him,” Cazenovia Republican, April 23, 1936, 10.

[5] Ibid, 2.

[6] Blakeslee, How My Father Secured Lincoln’s Autograph, 3-4.

[7] Blakeslee, “Lincoln As I Knew Him,” 10.

[8] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 7.

[9] Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time, ed. Herbert Mitgang (N.Y; Rinehart & Co., 1958), 224-226.

[10] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 7.

[11] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 8. Blakeslee wrote and spoke of this incident constantly throughout his life, practically every time he talked about Lincoln.

[12] F.D. Blakeslee to Major J.B. Merwin, June 29, 1910, in “J.B. Merwin and Abraham Lincoln” scrapbook, page 42, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

[13] Francis D. Blakeslee, quoted in Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln (Elmira, N.Y.: The Primavera Press, 1945), 430; also in Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 9.

[14] John W. Starr, New Light on Lincoln’s Last Day (Harrisburg, Pa.: privately printed, 1926); Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, 428-436; W. Emerson Reck, A. Lincoln: His Last 24 Hours (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1987), 49.

[15] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 10.

[16] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 9; Blakeslee, quoted in Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, 430.

[17] Blakeslee, “Lincoln As I Knew Him,” 10, Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 10.

[18] Blakeslee, Personal Recollections, 10-11.

[19] The book, “Autograph of Abraham Lincoln and Others,” is currently owned by Kim Nunnari.

[20] “Talked to Lincoln Later than Cabinet officers,” Cazenovia Republican, April 22, 1909, 1. This article reprints the Binghamton newspapers article.

[21] “Blakeslee Brings Autographs of Lincoln and Webster Here,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, August 18, 1934, 1.

[22] Blakeslee, “Lincoln As I Knew Him,” 10.

[23] James Cornelius, email to the author.

[24] Blakeslee, “The Story of the Autographs.”

[25] Dr. F.D. Blakeslee, Authority on Abraham Lincoln, Dies,” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 13, 1942.

[26] “Dr. Blakeslee is Ninety-Six,” Potsdam Herald-Recorder, Feb. 27, 1942, 4. This article is a reprint of the original Los Angeles Times article of Feb. 11, 1942.