Lincoln’s Strangest Document: The “Blind Memorandum” of August 23, 1864

Abraham Lincoln’s mature style as a writer and speaker was always terse, with little wastage of words. He loathed blow-hards, and remarked to a legal protégé in Illinois that one Chicago merchant who had turned politician “can compress the most words in the fewest ideas of any man I ever knew.”[i] Sometimes, however, the terseness could border on the cryptic, and no document of Lincoln’s is quite so cryptic, or quite so impenetrable, as the sixty words which comprise what Mark Neely, in his Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia, simply described as the “blind memorandum” of August 23, 1864.[ii] It reads:

Executive Mansion

Washington, Aug. 23, 1864.

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly

probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it

will be my duty to so cooperate with the Government President-elect,

as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he

will have secured his election on such ground that he can not

possibly save it afterwards.

On at least one level, the “blind memorandum” seems to be quite straight-forward:

- first, Lincoln has come to the conclusion that he will not be re-elected to the presidency in the November, 1864, national election

- second, he will plan to use the three months between the lost election and the inauguration of the new president (on March 4, 1865) to put on as much steam as possible to win the war; and

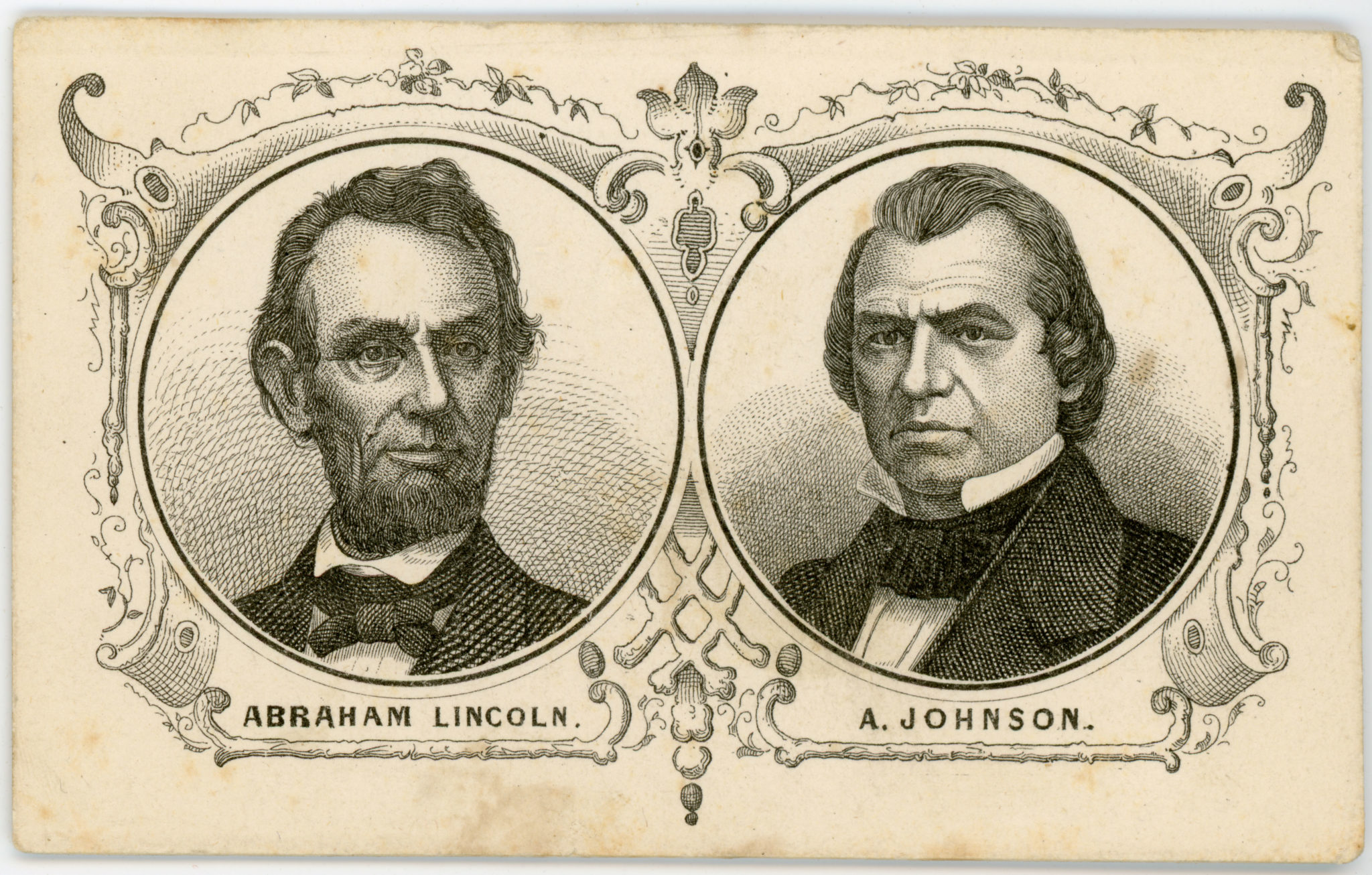

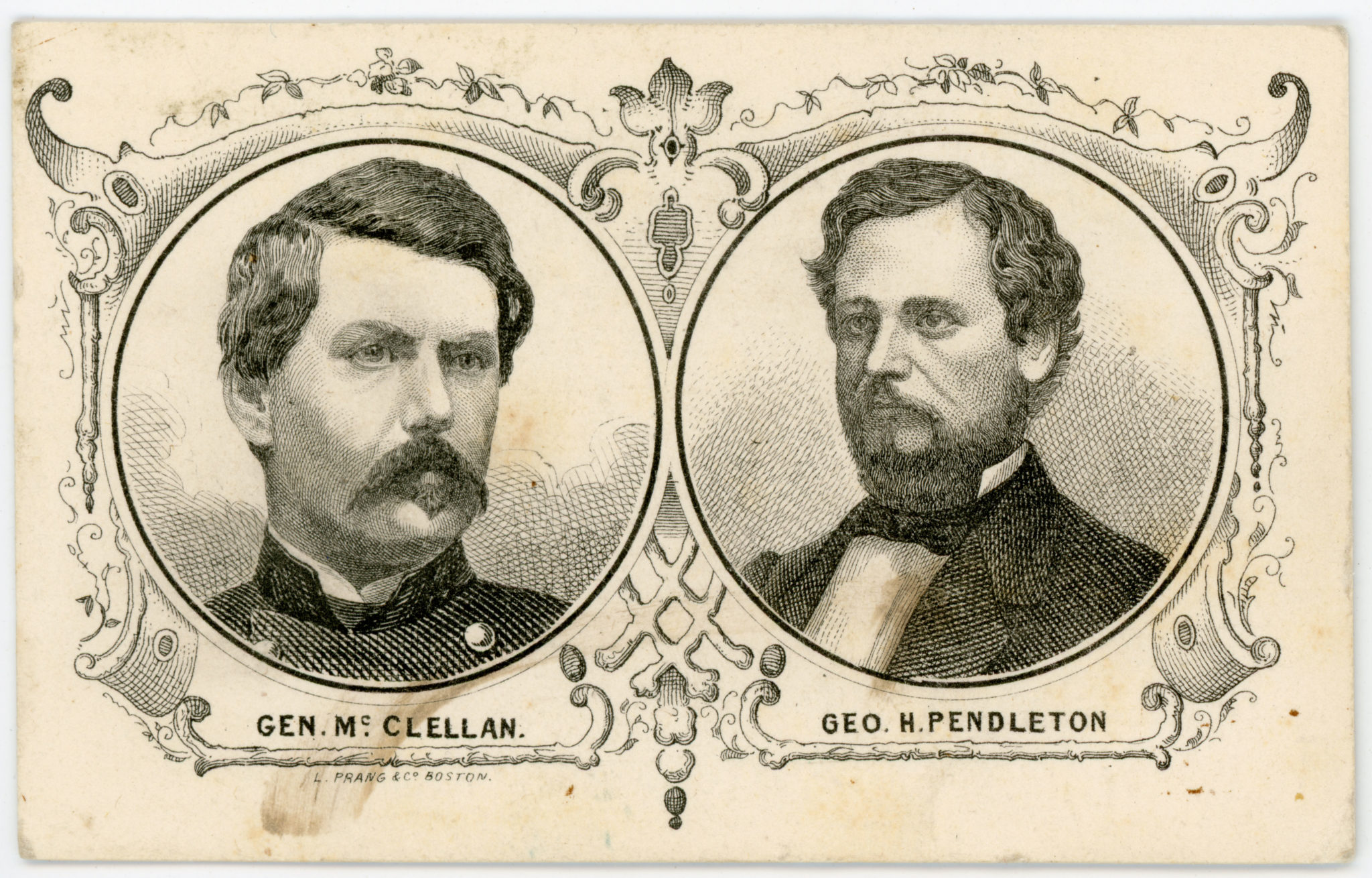

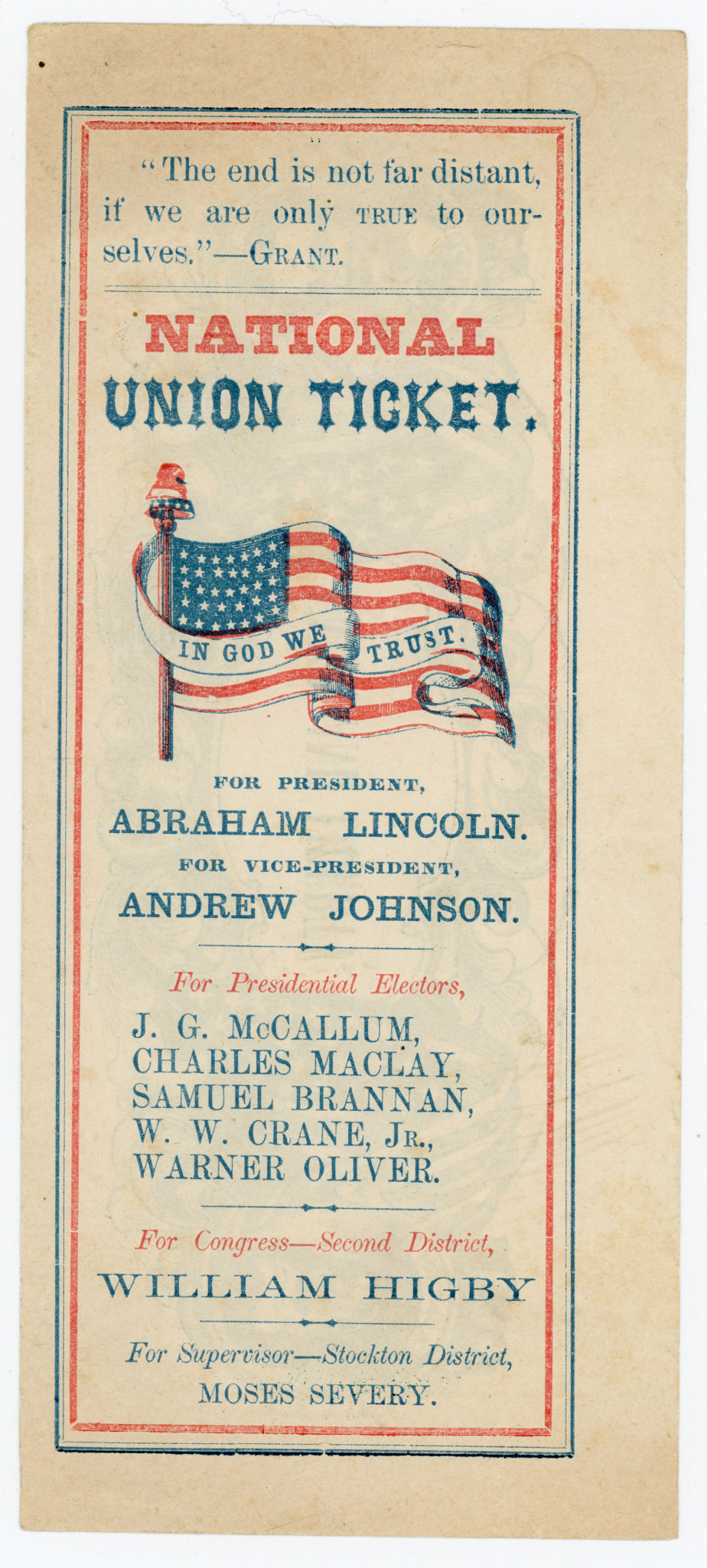

- third, this window of opportunity would only exist until March 4, 1865 because the new president – and no one doubted on August 23rd that the soon-to-assemble Democratic national party convention would nominate George B. McClellan as its candidate – would have been elected on a peace platform that would, once he actually became president, make it impossible (or at least unlikely) that the war would be won, much less continued.

This was not a terribly optimistic assessment of Lincoln’s political fortunes, especially coming from a president who had frequently expressed his determination to carry the war forward to a successful reconstruction of the Union, and without legalized slavery. Leonard Swett, who carried out a number of private missions for Lincoln during the war, remembered that Lincoln

kept a kind of account book of how things were progressing for three, or four months, and whenever I would get nervous and think things were going wrong, he would get out his estimates and show how everything on the great scale of action the resolutions of Legislatures, the instructions of delegates, and things of that character, was going exactly — as he expected.[iii]

Only a year before, in a public letter he wrote for a state-wide Republican “mass-meeting” in Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln had seized on the recent twin victories of Gettysburg and Vicksburg as evidence that “the signs look better” and that “peace does not appear so distant as it did.”[iv] And only days before the August 23rd memorandum, Lincoln had appeared to Wisconsin Governor Alexander Randall and Judge Joseph T. Mills to be “a man of deep convictions & an unutterable yearning for the success of the Union cause,” and convinced that he “should be damned in time & in eternity” if he backslid from the emancipation cause.[v] When Ulysses Grant quizzed him in the spring of 1865 whether he had “at any time” doubted “the final success of the cause,” Lincoln’s “prompt and emphatic” reply was Never for a moment, and he “leaned forward in his camp-chair and enforced his words by a vigorous gesture of his right hand.”[vi]

But Lincoln always had a realistic respect for contingency. There was, Lincoln told Grant, “a limit to the sinews of war, and a time might be reached when the spirits and resources of the people would become exhausted.”[vii] And then there was always the nagging metaphysical question of whether the Union cause was also God’s cause. Even in 1861, when Orville Hickman Browning (an old Lincoln friend who had been appointed to fill the U.S. Senate seat vacated by the death of Stephen A. Douglas) told Lincoln that “we can’t hope for the blessing of God on the efforts of our armies, until we strike a decisive blow at the institution of slavery,” Lincoln countered with the possibility of God having a different view of things. “Browning,” Lincoln replied, “suppose God is against us in our view on the subject of slavery in this country, and our method of dealing with it?”[viii]

In the most immediate political sense, the “blind memorandum” also reflects an element of realism in Lincoln’s assessment of what had happened – and not happened – over the spring and summer of 1864, when most of the contingencies looked like they had gone disastrously awry.

- Grant’s Overland Campaign, which had jumped-off with high expectations that it would finish the war in 1864, had instead turned into a series of costly head-to-head battles across northern Virginia, ending in nothing more decisive than a siege of the Confederate capital at Richmond.

- The co-ordinated campaigns Grant had entrusted to William T. Sherman (in Georgia), Franz Sigel (in the Shenandoah Valley), Ben Butler (on the James River) and Nathaniel Banks (against Mobile, Alabama) had produced even less: Sherman had tick-tacked across northern Georgia and was now locked in another apparently-pointless siege, of Atlanta; Sigel’s campaign in the Shenandoah Valley had been blunted and then reversed as a Confederate raid under Jubal Early stormed down the Valley, crossed into Maryland, and in July even threatened the outskirts of Washington; Ben Butler landed his Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred and proceeded to threaten Richmond, only to be driven back into the Bermuda Hundred peninsula “like a bottle tightly corked;” and Nathaniel Banks took his own counsel and launched a botched operation up Louisiana’s Red River from which his command escaped by the skin of its teeth.

- The federal conscription law, signed by Lincoln in March 1863, had triggered a wave of urban riots in the North (which frequently turned into racial pogroms), and three new draft calls in February, March and July of 1864 stimulated so much flight to Canada that a Toronto newspaper reported that “our towns and villages, not only on the frontier, but inland, are crowded with motley groups of fugitives from the draft.”[ix]

- Even within Lincoln’s own Republican party, Radicals who were unhappy with the leniency of the Reconstruction plan he had announced in December were challenging him, first with a rival plan which he pocket-vetoed in July, and then with a ‘dump-Lincoln’ insurgency which called its own convention in Cleveland and nominated a rival presidential candidate, John Charles Frémont.[x] At the same time, a ‘conservative unionist’ faction at the other end of the Republican party also considered mounting a challenge to Lincoln, claiming that he had changed “the character of the war from the single object of upholding the Government to that of a direct interference with the domestic institutions of the States.”[xi]

“We have,” wrote Noah Brooks with considerable understatement, “a forbidding picture to contemplate.”[xii]

No wonder, after such a cascade of bad news, that Lincoln irritably informed New York politician Schuyler Hamilton that “You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do, and unless some great change takes place, badly beaten…. The people promised themselves when General Grant started out that he would take Richmond in June. He didn’t take it, and they blame me….”[xiii]

Ultimately, however, the ‘blind memorandum” also represents a darker aspect of Lincoln’s psyche: his weakness for depression, not unmixed with self-pity, and his expectation, under stress, that the likeliest results were usually the worst ones. “I have hours of depression,” Lincoln admitted to Iowa congressman Josiah B. Grinnell, “You flaxen men with broad faces are born with cheer and don’t know a cloud from a star. I am of another temperament.”[xiv]

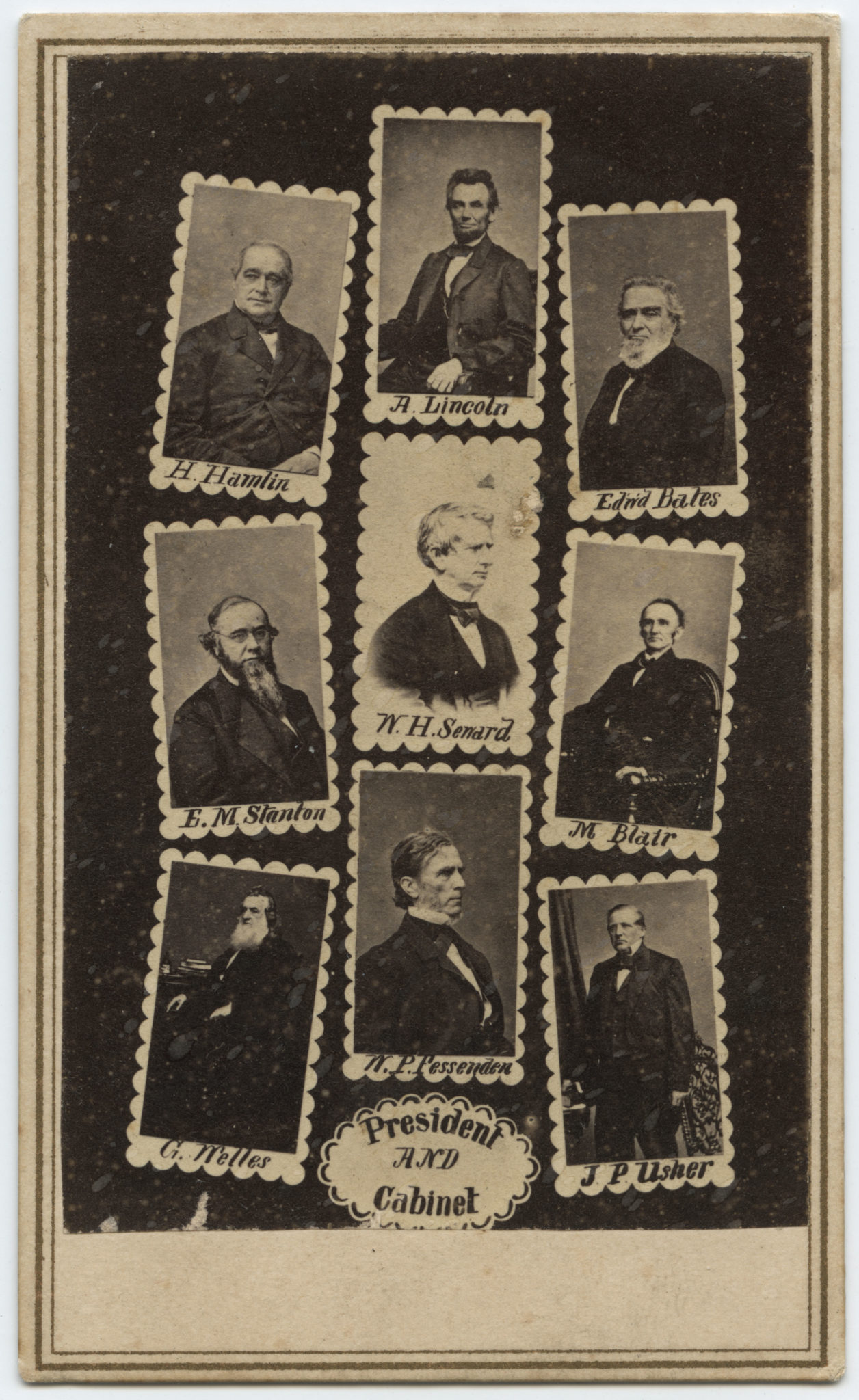

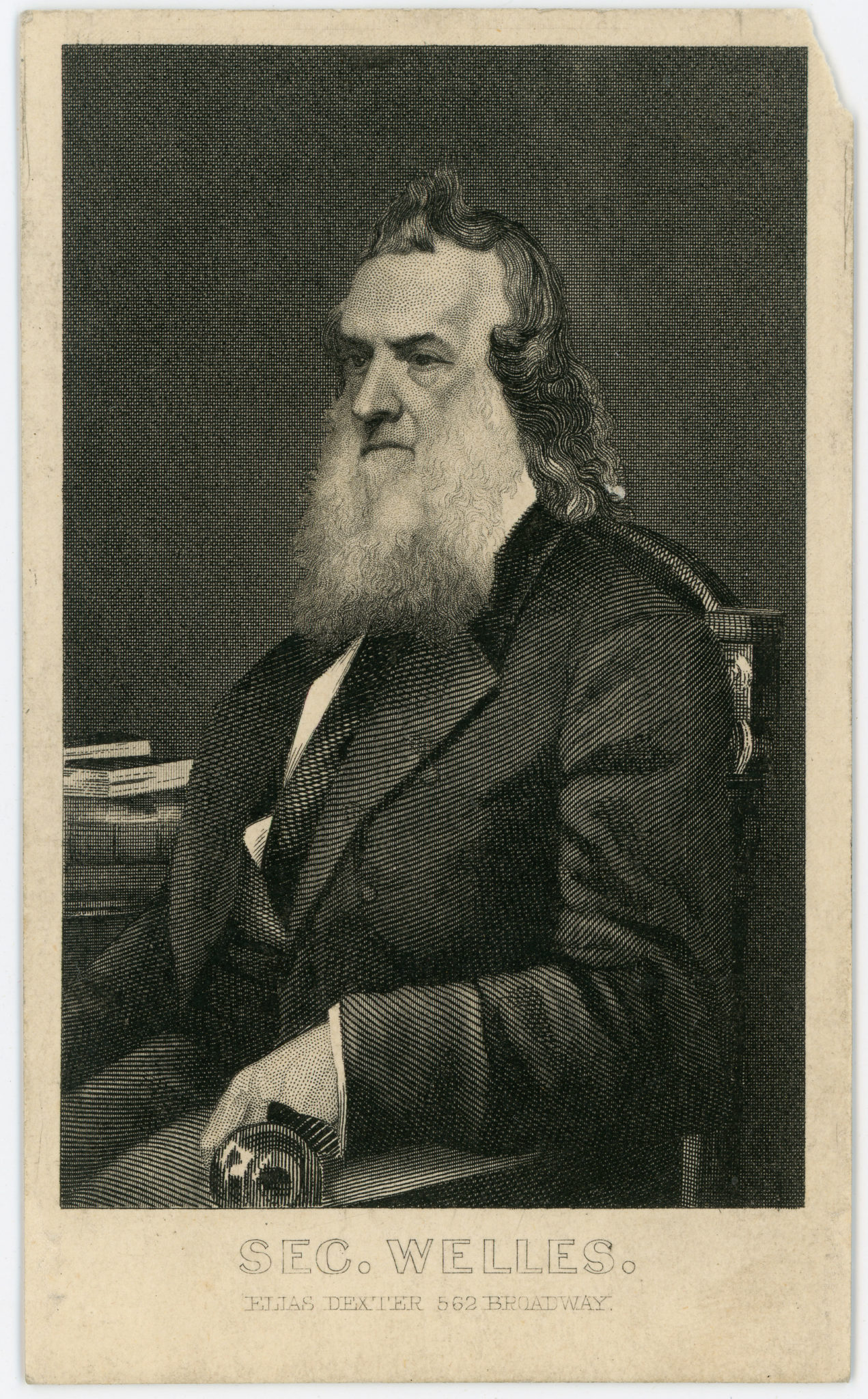

These factors seem to suggest that the “blind memorandum” should be read simply as a confession of despair, from a man with plenty of reason to feel despairing. But immediately behind them crowd a series of questions which render the memorandum even more curious. Begin with the audience for which he intended this little piece of political drama: his cabinet, which on August 23rd was composed of William Henry Seward (State), Edwin M. Stanton (War), William Pitt Fessenden (Treasury, having just replaced Salmon Chase the month before), Gideon Welles (Navy), Edward Bates (Attorney-General, although only until the end of the year), Montgomery Blair (Postmaster-General), and John Palmer Usher (Interior).

We know that the “blind memorandum” was intended as an item of cabinet business on August 23rd, although that knowledge comes surprisingly long after the fact. Of the two great diary-keepers in the Cabinet, Edward Bates has no entry at all for August 23rd and the published edition of Gideon Welles’ diary for that day has only a lengthy rant about official Washington’s lack of recognition for the accomplishments of the Navy and of David Farragut in particular.

No mention of the “blind memorandum” appears in the diary or correspondence of Lincoln’s secretarial staffers, John Hay and John G. Nicolay, and in fact no first-person description of the “blind memorandum” appeared at all until 1877, when Gideon Welles, in an article written for the Galaxy, described how Lincoln, “borne down with the anxiety and labor of recruiting, reinforcing, and supplying the army,” met him as he arrived for the regular Tuesday cabinet meeting on August 23rd with “a sealed envelope,” and

a request that I would write my name across the back of it. One or two members of the Cabinet had already done so. In handing it to me he remarked that he would not then inform me of the contents of the paper enclosed, had no explanation to make, but that he had a purpose, and at some future day I should be informed of it, and be present when the seal was broken.[xv]

Sure enough, the reverse of the “blind memorandum” contains the signatures of all seven cabinet secretaries, Welles fourth in order after Seward, Fessenden and Stanton, and dated in Lincoln’s hand again.

Lincoln was as good as his word. On November 11, 1864 – three days after what turned out to be a triumphant re-election – Lincoln again began a cabinet meeting with the “blind memorandum” in hand, and this time with John Hay’s diary as a witness:

At the meeting of the Cabinet today, the President took out a paper from his desk and said, “Gentlemen do you remember last summer I asked you all to sign your names on the back of a paper of which I did not show you the inside? This is it. Now, Mr Hay, see if you can get this open without tearing it!”: He had pasted it up in so singular [a] style that it required some cutting to get it open. He then read as follows….[xvi]

From that moment, the “blind memorandum” suddenly became a novelty, and as Hay recounted to Nicolay in a letter in 1878 (after the publication of Gideon Welles’ article in the Galaxy), members of the Cabinet began clamoring for copies, starting with Edward Bates, followed by Welles, “then everybody.” Hay told Nicolay that he “cussed silently” at these requests, but in fact Hay made a copy for himself and even had the Cabinet secretaries endorse it as they had the original.[xvii]

But far from answering any questions about the meaning of the “blind memorandum,” the peculiar mode of its two-stage presentation to the cabinet only deepens the mystery. Why, in the first place, did Lincoln think in August that a memorandum about his prospective defeat in the upcoming election should be presented to the cabinet, and why, when he presented it, did he then refuse to let them see the contents (hence, the “blind” part of the memorandum)? It has been suggested that Lincoln feared the document might be leaked; but in that case, why should he have written it at all? Nor does any of this explain why (in the second place) he wanted the cabinet to endorse it, as though they were witnessing his last will and testament. If witnesses were all he wanted, Nicolay and Hay would surely have done as well as anyone.

The waters grow considerably muddier when we turn to asking what the “blind memorandum” actually proposed as Lincoln’s course of action in the event of his defeat. The memorandum states simply that he would “so co-operate with the President-elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration.” Yet, the explanation Lincoln offered to his cabinet on November 11th makes it clear that this is exactly what he did not expect would happen. “I resolved,” he explained (according to Hay’s diary),

In the case of the election of General McClellan, being certain that he would be the Candidate, that I would see him and talk matters over with him. I would say, “General, the election has demonstrated that you are stronger, have more influence with the American people than I. Now let us together, you with your influence and I with all the executive power of the Government, try to save the country. You raise as many troops as you possibly can for this final trial, and I will devote all my energies to assisting and finishing the war.”

Given the rocky road the Lincoln and McClellan had travelled in 1862, the idea of co-operation between them seems almost risible. But McClellan remained enormously popular with the Army of the Potomac (less than a year before, Secretary of War Stanton had had to squelch a movement among the Army of the Potomac’s senior officers to create a ‘memorial’ to McClellan), and the likelihood of his nomination to oppose Lincoln had been a virtual given since the fall of 1863, when McClellan had publicly endorsed George Woodward, the Democratic candidate in the crucial governor’s election in Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 1864, Lincoln had suggested out-flanking McClellan’s political ambitions by re-calling him to a major command – “a military place in which he could be most useful,” as Montgomery Blair described it – and Lincoln used Francis Preston Blair as an emissary to McClellan in New York. What exactly was offered is unknown: perhaps appointment as a glorified chief-of-staff under Grant as general-in-chief, perhaps even displacing George Meade at the head of the Army of the Potomac.[xviii] And in a secret high-level meeting at Fortress Monroe, the subject of McClellan again came up between Lincoln and Grant yet again in July.[xix]

McClellan, however, ignored these suggestions: he understood all too well that this ploy was intended to prevent “my name to be used as a candidate for the Presidency.” And, in fact, Lincoln expected to be ignored again, because on November 11th, Secretary of State Seward interrupted Lincoln to protest that even if Lincoln humbled himself sufficiently to invite McClellan to co-manage what would have been left of Lincoln’s term in office, McClellan would find some way to dither out of Lincoln’s grasp: “The General would answer you, ‘Yes, Yes’; and the next day when you saw him again & pressed these views upon him he would say ‘Yes—yes’ & so on forever and would have done nothing at all.” Lincoln’s response was short and dismissive. “At least,” he replied, “I should have done my duty and have stood clear before my own conscience.”[xx]

But this only begs the question of why Lincoln’s conscience should have needed McClellan, of all people, as its salve. Why should Lincoln not simply have said that (as president of the United States) he remained president until March 4, 1865, and would prosecute the war with renewed zeal, entirely on his own, without involving McClellan (from whom he expected no co-operation anyway)? For that matter, why did he even need to say that much, since no one would have been in the least surprised if Lincoln had kept the machinery of war in full force until his last hour in the White House? And why should he need the witness of seven cabinet members to show that he had thought that way in August?

The fundamental clue to unraveling Lincoln’s skein of thinking occurs in the last sentence of the “blind memorandum”: You raise as many troops as you possibly can for this final trial, and I will devote all my energies to assisting and finishing the war. McClellan, in other words, was needed as a magnet for recruitment and, especially in the summer of 1864, re-enlistment of the three-year Volunteers whose terms of service were ending; and indeed, if Lincoln had gone down to defeat at the polls on November 8th, the task of both recruitment and conscription would probably have been rendered difficult, if not impossible, and with it any hope of a successful conclusion to the war. An announcement of McClellan’s willingness to co-operate in some interim co-presidency would sustain enlistment, keep up conscription, and most important, ensure that the veterans of the Army would renew their terms of service when asked-to by Little Mac.[xxi]

But wooing McClellan into some form of temporary interregnum between November and March might succeed in achieving a second goal, as well, and that would be splitting McClellan from the larger web of his Democratic Party backers. After all, Lincoln’s Republicans had renamed themselves in 1864 as the ‘National Union Party’ with precisely the aim of wooing War Democrats to their banner, and Lincoln had even accepted as his vice-president exactly such a Democrat in Andrew Johnson. Co-opting McClellan would not depart very far from that strategy. It has been almost routine, reflecting on the conflict between Lincoln and McClellan in 1862, to imagine that these two were forever irreconcilable, and that they represented two polar ends of the political spectrum.

But McClellan, whatever his other faults, was a Unionist – which is to say that he understood “the original object of the war” to be “the preservation of the Union, its Constitution & its laws,” and was “convinced that the Union of the States should never be abandoned.” Much as he criticized “a course which unnecessarily embitters the inimical feeling between the two sections,” he told Francis Preston Blair that he also would “deprecate a policy which far from tending to that end tends in the contrary direction,” and still ends up in disunion. McClellan was also, in the end, a War Democrat. He roundly condemned Ohio Democrat George Washington Morgan’s call on August 4th for “an armistice,” spluttering that “these fools will ruin the country.”[xxii] And when he finally was nominated by the Democratic national convention in Chicago on August 31st, he labored through six drafts of an acceptance letter which eventually declared that he “cannot realize that the existence of more than one Government over the region which once owned our Flag is compatible with the peace, the power & the happiness of the people.”[xxiii]

This contrasted, with embarrassing sharpness, with the prevailing temper of McClellan’s party. The Chicago convention turned into a bacchanalia of anti-war fervor. The principal voices belonged to the Copperheads – the Peace Democrats, Clement Vallandigham, Alexander Long and Benjamin Gwinn Harris — while Samuel S. Cox, the Democratic minority leader in the House, was heckled with shouts of “Get down, you War Democrat!” and “Vallandigham! Vallandigham!” The party platform included a specific repudiation (written by Vallandigham) of the war and a call for an immediate armistice:

after four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war, during which, under the pretense of a military necessity, or war power higher than the Constitution, the Constitution itself has been disregarded in every part, . . . the public welfare demands that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities with a view to an ultimate convention of the States, or other peaceable means to the end that at the earliest practicable moment peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal union of the States.

The chair of the convention, New York’s Horatio Seymour, had come to Chicago precisely to prevent the Peace Democrats from running the show, but in the face of the Peace Democrats’ vehemence, Seymour studiously avoided criticizing them. Not even McClellan was exempt from cat-calls: Alexander Long attacked McClellan as “this weak tool of Lincoln’s,” and Benjamin Harris lustily asked “Will you vote for such a man? I never will!”[xxiv]

Could a president-elect McClellan be peeled away from the loons of his own party, especially when invited by Lincoln to take up a military man’s hand and join in saving the Union, and especially over the four months when he would not have Peace Democrats hounding him from cabinet seats or from newly-won seats in Congress? The Peace Democrats were noisy, but not as numerous as their noise suggested. Lincoln, in the same situation in 1860, had been begged by frantic Democrats and Unionist Whigs to issue some statement qualifying the Republican platform in order to head off secession, even to the point of abandoning his opposition to popular sovereignty in the territories.[xxv] Why not McClellan, too? After March 4th, McClellan’s options would shrink, since he would be surrounded by a cabinet which would have to include Peace Democrats, and compelled to conform to the dictates of a party which will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it [the Union] afterwards.

Given the stakes, it was certainly worth Lincoln’s time to think about a strategy for unmooring McClellan from the Copperheads long enough to finish the war; but it was not worth thinking about it in public where the idea would dishearten his own party faithful. Still, it would demonstrate the sincerity of the offer if it could be shown that Lincoln had been contemplating this offer for a considerable period of time before the election, and not merely as a last-second ploy to hamstring McClellan’s victory. Hence, the resort to a memorandum, describing the offer; hence also, the desire not to reveal its contents, but to have the cabinet, as the senior officials of the administration and the people who would have to participate in this experiment, endorse the “blind memorandum” as proof of its genuineness.

This would certainly have been something of a constitutional anomaly, or at least a departure from anything that looked like conventional practice in presidential transitions. The Constitution dictated only that “Congress may determine the…Day” on which presidential voting should occur (not until January, 1845, did Congress even stipulate that “the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November” would be the uniform day for presidential elections) and the 12th Amendment laid down March 4th as the conclusion of a presidential term.[xxvi]

Apart from that, nothing was said about what relationship, if any, the outgoing president and president-elect should have, and in the most notorious cases – John Adams, sitting up til midnight on March 3rd, signing judicial commissions, and John Quincy Adams leaving town so as to avoid the spectacle of Andrew Jackson’s inauguration – the less said between the two was often the better. On the other hand, Martin Van Buren had graciously offered to move out of the White House two weeks before William Henry Harrison’s inauguration in order to accommodate the old Whig general, and James Knox Polk yielded the presidency to Zachary Taylor in 1849 riding “beside General Taylor in the carriage that conveyed them to the capitol” and “rejoicing, meanwhile, that he was himself relieved from the cares and anxieties of public life.”[xxvii]

But there was no precedent for the kind of co-operative interim Lincoln described in the “blind memorandum” – for meeting with McClellan or “assisting” him — thus no incentive on McClellan’s part to join it. In the end, as he admitted on November 11th, Lincoln regarded the likelihood of McClellan grasping a co-operative hand to finish-up the war as remote, although this was not because McClellan (as Seward complained) was an inveterate ditherer. Lincoln offered McClellan a partnership, but not the sacrifice of principle Lincoln had been asked to make in 1860. The “blind memorandum” presented McClellan and the Democratic party with no pay-off – no willingness to consider an armistice if Lincoln’s little entente with McClellan failed to keep the armies in the field, no offers of compromise on tariffs, banks, railroads and other issues so dear to the Democratic heart, and above all else, no step backwards on emancipation. Much as McClellan was willing to “resort to the dread arbitrament of war…for the restoration of the Union,” he was as silent as the Sphinx on the survival and extension of slavery, the status of the Emancipation Proclamation, and the rendition of contrabands and fugitives which Lincoln had declared he would be “damned in time & eternity” if he would allow.[xxviii]

We cannot see the “blind memorandum” more mistakenly than if we take it, as Gideon Welles did in 1877, as a statement of Lincoln’s despair, or as merely another example of Lincoln’s penchant for burying layers of meaning under short, Delphic phrases. The “blind memorandum” was actually a document of determination, that even in the worst case, Lincoln intended to move forward toward victory, even if it took an unconventional route. It was also a canny determination, pointed toward exploiting the rift within George McClellan’s own party. And, one might say, it was also a humble determination, since in the “blind memorandum” Lincoln announced a willingness, as he had once said, “to hold McClellan’s horse if he will only bring us success.”[xxix]

Despite McClellan’s outrageous behavior toward Lincoln, passing the boundaries of insubordination and bordering in 1862 on treason, Lincoln “always felt kindly toward McClellan, and desired to befriend him as far as political necessities permitted,” and in this dire circumstance was even willing to share the laurels of a prospective victory.[xxx] At the same time, that humility had its limits: the “blind memorandum” envisions Lincoln staying in the presidential race and losing, but not Lincoln stepping aside in the face of certain defeat to allow a different candidate to run in his place.

Surprisingly, for a man who often described himself as “an old Henry Clay Whig,” Lincoln was willing to explore a constitutional and political ambiguity which might well have had enormous consequences for presidential transitions in the future. But, as Lincoln had half-feared and half-expected, the “blind memorandum” and its proposal came to naught, not so much by McClellan’s response as because of the news of victories at Mobile Bay and elsewhere, and even more momentous victories shortly to be won in September and October by William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan, and then followed by Lincoln’s re-election on November 8th. And in any event, he would be secure in the knowledge that he had “done my duty and have stood clear before my own conscience” – something which, for any politician, is no small accomplishment.

Allen Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College and the William L. Garwood Visiting Professor for the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University (2017-18). He is a winner of the 2018 Bradley Prize.

[i] Whitney, Life on the Circuit with Lincoln, ed. Paul Angle (Caldwell, ID: Caxton printers, 1940), 183.

[ii] “Blind Memorandum,” in The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia, ed. Mark E. Neely (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), 32; “Memorandum Concerning His Probable Failure of Re-election,” in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7:514. Neely was probably the first to call this document the “blind memorandum,” in “The Lincoln Theme Since Randall’s Call,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 1 (1979), 18.

[iii] Swett to W.H. Herndon (January 17, 1866), in Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Statements, and Interviews about Abraham Lincoln, eds. R.O. Davis & D.L. Wilson (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 165.

[iv] “To James C. Conkling” (August 26, 1863), CW, 6:409-410.

[v] Joseph T. Mills, diary entry for August 19, 1864, in Conversations with Lincoln, ed. Charles M. Segal (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1961), 339-340.

[vi] Horace Porter, Campaigning With Grant (New York: Century, 1906), 408.

[vii] Horace Porter, “Lincoln and Grant,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, ed. Peter Cozzens (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 6:79.

[viii] “Conversation with Hon. O.H. Browning” (June 17, 1875), in An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, ed. Michael Burlingame (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), 5.

[ix] Toronto Globe (August 11, 1863), in Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War, 1863-1864 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971), 129.

[x] Andrew F. Rolle, John Charles Frémont: Character As Destiny (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 230.

[xi] William C. Harris, “Conservative Unionists and the Presidential Election of 1864,” Civil War History 38 (December 1992), 310. This included old Lincoln allies John Todd Stuart and Orville Hickman Browning; see John Hay to John G. Nicolay (August 25, 1864), in At Lincoln’s Side: Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 93.

[xii] “A Military Failure” (August 1, 1864), in Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, ed. Michael Burlingame (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 129.

[xiii] Hamilton (August 11, 1864), in Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words, 196-197.

[xiv] Grinnell, Men and Events of Forty Years: Autobiographical Reminiscences of an Active Career from 1850 to 1890 (Boston: D. Lothrop, 1891), 171.

[xv] Welles, “The Administration of Abraham Lincoln, V” in Lincoln’s Administration: Selected Essays by Gideon Welles, ed. Albert Mordell (New York: Twayne, 1960), 176-177; David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln’s Re-election and the End of Slavery (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994), 189; John Waugh, Re-electing Lincoln: The Battle fort the 1864 Presidency (New York: Crown, 1997), 269-270.

[xvi] Hay, diary entry for November 11, 1864, in Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, eds. Michael Burlingame & J.R.T. Ettlinger (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 247; Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 2:675; Waugh, Re-electing Lincoln, 360.

[xvii] Hay to John G. Nicolay (February 27, 1878), in William Roscoe Thayer, The Life and Letters of John Hay (New York: Houghton & Mifflin, 1915), 2:22.

[xviii] McClellan to Blair (July 22, 1864), in The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, ed. Stephen W. Sears (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1989), 583; see also Montgomery Blair’s comment, op cit, 575; Paul D. Escott, Lincoln’s Dilemma: Blair, Sumner, and the Republican Struggle over Racism and Equality in the Civil War Era (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014), 179.

[xix] “From Fortress Monroe – Interview between the President and Gen. Grant,” New York Times (July 31, 1864); “To Julia Dent Grant” (July 30, 1864), in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 11:356; “To Ulysses S. Grant,” (July 29, 1864), in CW 7:470; John Y. Simon, “Grant, Lincoln and Unconditional Surrender,” in The Union Forever: Lincoln, Grant, and the Civil War, ed. Glenn W. LaFantasie (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 218.

[xx] Hay, diary entry for November 11, 1864, in Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, 248.

[xxi] Matthew Pinsker, “Seeing Lincoln’s Blind Memorandum,” in Lincoln and Leadership: Military, Political and Religious Decision-Making, ed. Randall Miller (New York: Fordham University Press, 2012), 74.

[xxii] McClellan to William C. Prime (August 10, 1864), in Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, 586.

[xxiii] “To the Democratic Nomination Committee” (September 4, 1864), in Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, 590; Ethan S. Rafuse, McClellan’s War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 383; Stephen W. Sears, “McClellan and the Peace Plank of 1864: A Reappraisal,” Civil War History 36 (March 1990), 63-64.

[xxiv] Noah Brooks, “Two War-Time Conventions,” Century Magazine 49 (March 1895), 732-733; James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress: From Lincoln to Garfield (Norwich, CT: Henry Bill, 1884), 1:528-529; “Democratic National Platform, 1864,” in The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction, ed. Edward McPherson (Washington: Solomons & Chapman, 1875), 118; William C. Harris, Two Against Lincoln: Reverdy Johnson and Horatio Seymour, Champions of the Loyal Opposition (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 176..

[xxv] “To John D. Defrees” (December 18, 1860), in CW 4:155; Mark E. Neely, Lincoln and the Democrats: The Politics of Opposition in the Civil War (New York” Cambridge University Press, 2017), 86-96.

[xxvi] The Public Statutes-at-Large of the United States of America, ed. Richard Peters (Boston: Little, Brown, 1856), 5:721.

[xxvii] John Niven, Martin Van Buren: The Romantic Age of American Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 478; John S. Jenkins, James Knox Polk, and a History of His Administration (New Orleans: Burnett & Bostwick, 1854), 323.

[xxviii] “To the Democratic Nomination Committee” (September 4, 1864), in Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, 591.

[xxix] Ormsby Mitchell, in Recollected Words, 332.

[xxx] Edward H. Wright (December 26, 1886), in William Styple, McClellan’s Other Story: The Political Intrigue of Colonel Thomas M. Key, Confidential Aide to General George B. McClellan (Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Press, 2012), 289.