Marx and Lincoln

Marx and Lincoln by Jeffery R. Kerr-Ritchie

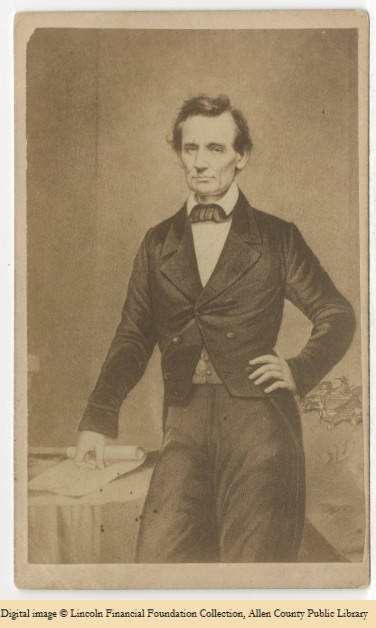

In November 1864, Abraham Lincoln was re-elected president of the United States. Numerous bodies outside America welcomed his re-election. One such was the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA).

The IWMA was officially founded on September 28, 1864, at St. Martin’s Hall in central London. Its members were mostly European radicals, socialists, communists, anarchists, trade unionists, artisans, and working people. Its central objective was to organize the working-class internationally in a struggle against industrial capitalism and for the establishment of socialist societies. One expanding group consisted of immigrant laborers who had settled in the United States over the previous several decades. They worked the fields, factories, towns, and ships of the massive new republic and required inclusion in this global crusade.

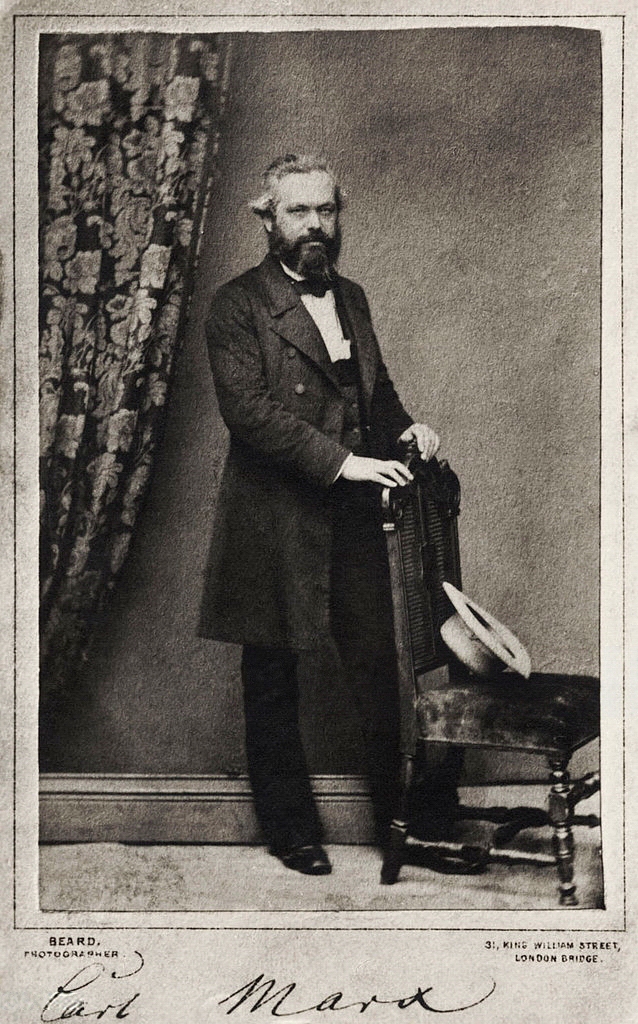

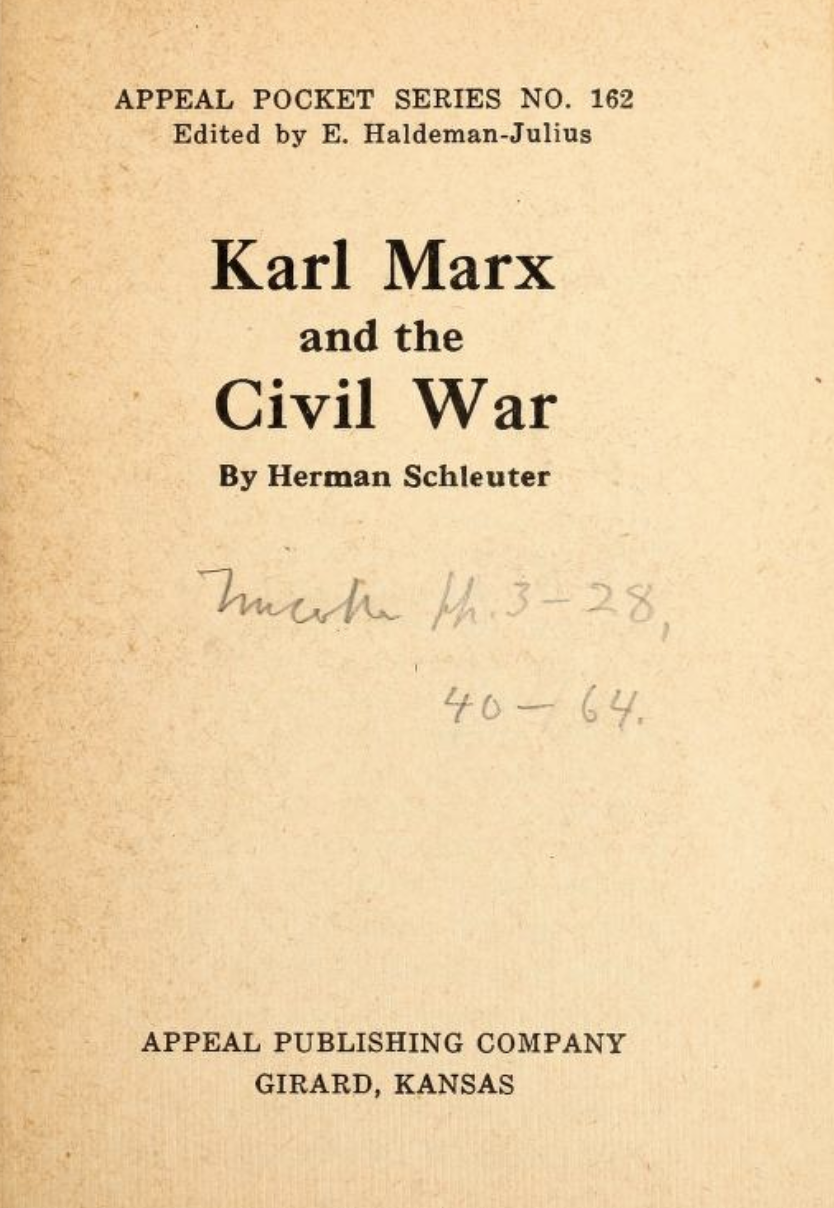

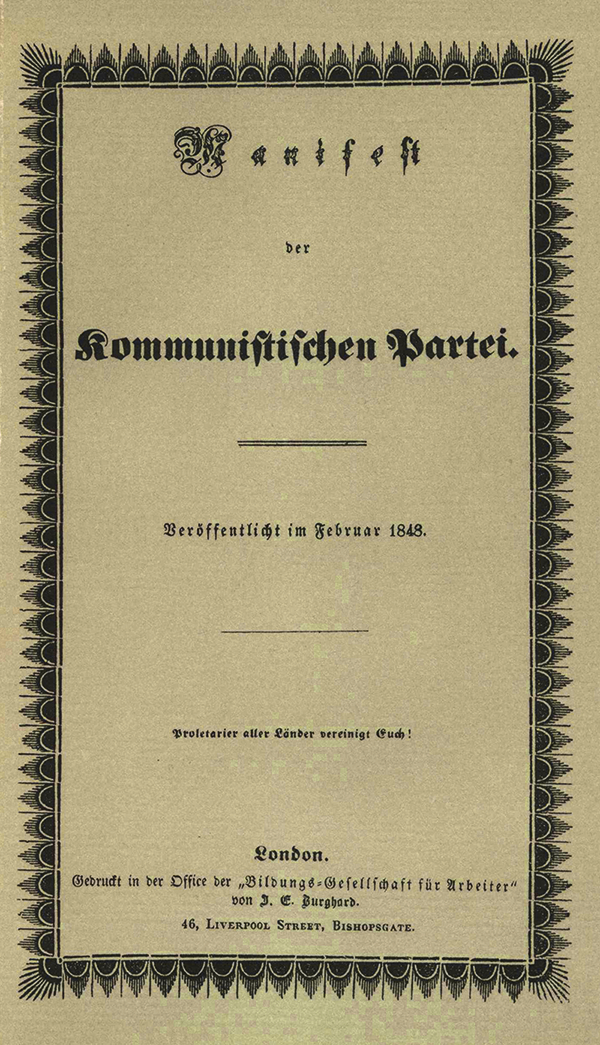

On November 29, 1864, the Central Council of the IWMA drafted an Address to President Lincoln. The organization’s Corresponding Secretary for Germany wrote it in English. This man, Karl Marx, was forty-six years old at the time (compared to the fifty-five year old Lincoln) and living as an exile in central London. He had been persona non grata since the publication of the explosive call for international working class solidarity expressed in The Communist Manifesto published during the early months of the 1848 European Revolutions.

The 1864 Address made four key points. First, it offered congratulations to the president for his consistent opposition toward slavery. In the first presidential election in 1860, Lincoln’s watchword had been “resistance to the Slave Power.” In his second election of 1864, it was the “Death of Slavery.” Both met with the approbation of his supporters. What is striking about this opening point is that even contemporary outsiders recognized that the American Civil War was primarily about slavery.

Second, the working class of Europe had a vested interest in this “titanic American strife.” It boiled down to one simple proposition: was the “virgin soil of immense tracts” to be available to the “emigrant” or was it to be “prostituted by the tramp of the slavedriver?”

Again, this was a powerful statement on the role of differences concerning slavery’s expansion in the new republic as being foundational to civil war causation.

Third, this was a global struggle between capital and labor. On the one side, a slaveholders’ rebellion representing a “holy crusade of property against labor.” Opposed were “men of labor” with future hopes and aspirations. Their opposition was firmly expressed in bearing hardships during the cotton famine in which factories stood idle and working people starved because of the absence of the southern staple crop. These workers had also opposed intervention by respective European governments to support proslavery interests. And immigrants were joining Union armies and contributing their “quota of blood” to the good cause.

This third point is based upon some questionable assumptions. Not all factory operatives in the textile districts of Lancashire in northern England supported the Union. It is not at all clear how working people were interested in stopping their respective governments from recognizing the Confederacy. Also, immigrants who fought for the United States often did so under compulsion rather than as part of a holy crusade under the banner of international solidarity. One powerful representation is the movie scene of Irish immigrants getting off ships in New York City harbor and being immediately drafted into the Union army in Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York.

The fourth point of the 1864 Address was that the Civil War was historically progressive. Before it, northern labor was unable to attain “true freedom” because slavery “defile[d] their own republic,” and they were forced to sell their labor to the highest bidder. Moreover, American workers were unable to support their European brethren while being subservient to capital. Now this was over.

The IWMA Address to Lincoln concluded that this War was a historical watershed in terms of ushering in history’s progressive class. If the Revolutionary War brought in the rule of the “middle class,” so the “American Antislavery War” would usher in the ascendancy of the working class. It was only appropriate that Lincoln, “the single-minded son of the working class,” should lead this epochal struggle. Again, historical accuracy was sacrificed for sweeping rhetoric. As we know, Lincoln’s famous log cabin image should not be confused with his more comfortable and successful legal and political careers. Moreover, it is hard to see how the middle class became ascendant after the American Revolution. Rather, the price of a successful anti-colonial struggle was an independent nation that protected property—including enslaved people as chattel—which resulted in the making of the most powerful slaveholding republic in human history and its contestation by moral abolitionists and political anti-slavers which led to civil conflagration in the 1860s.

Fifty eight members of the Central Council of the IWMA signed the Address. These included some interesting signatories. Bavarian-born Louis Wolff served as secretary to exiled Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini during the 1860s. English artisan and trade unionist George Howell moved up (or down depending on your view) from radical circles to service as a Member of Parliament from 1885 to 1895. Johann Eccarius was a Thuringian- born tailor and activist who served as the corresponding secretary with American supporters during the 1870s. The Address was then sent to Ambassador Charles Francis Adams at the American Legation. He penned a response dated January 28, 1865.

The U.S. ambassador and prominent scion of the presidential family informed the IWMA secretary William Cremer that the Address had been transmitted and received by Lincoln. The president willingly accepted the “sentiments” from “his fellow citizens” (Lincoln never forgot his political obligations even in a private letter!) as well as “friends of humanity and progress” globally. Moreover, the government of the United States insisted on refraining from “propagandism and unlawful intervention” in pursuit of “equal and exact justice to all states and to all men.” President Lincoln had his eye on the presidential reconstruction of the post-bellum Union. Finally, this present conflict was of universal significance. The nation’s conflict with “slavery-maintaining insurgents” represented the cause of human nature. As such, the nation was emboldened by the fact that the “workingmen of Europe” supported the “national attitude.” The Address was first published in the London Daily News on December 23, 1864. (Both documents can be accessed here ).

Perhaps the most striking feature of this correspondence was its emphasis on different forms of progress. President Lincoln saw the death of slavery as the opening of a new chapter in United States history. This was equal and exact justice “to all men.” One can trace this egalitarian creed back to the 1863 Gettysburg Address as well as the 1776 Declaration of Independence. Its future lay in greater happiness for Americans. Alternatively, the IWMA believed that the American War on Slavery would result in the emergence of working class rule globally. One could argue that the following decades did indeed see a remarkable historical emergence of organized labor globally. Its international solidarity was to perish brutally on the killing fields of the First World War.

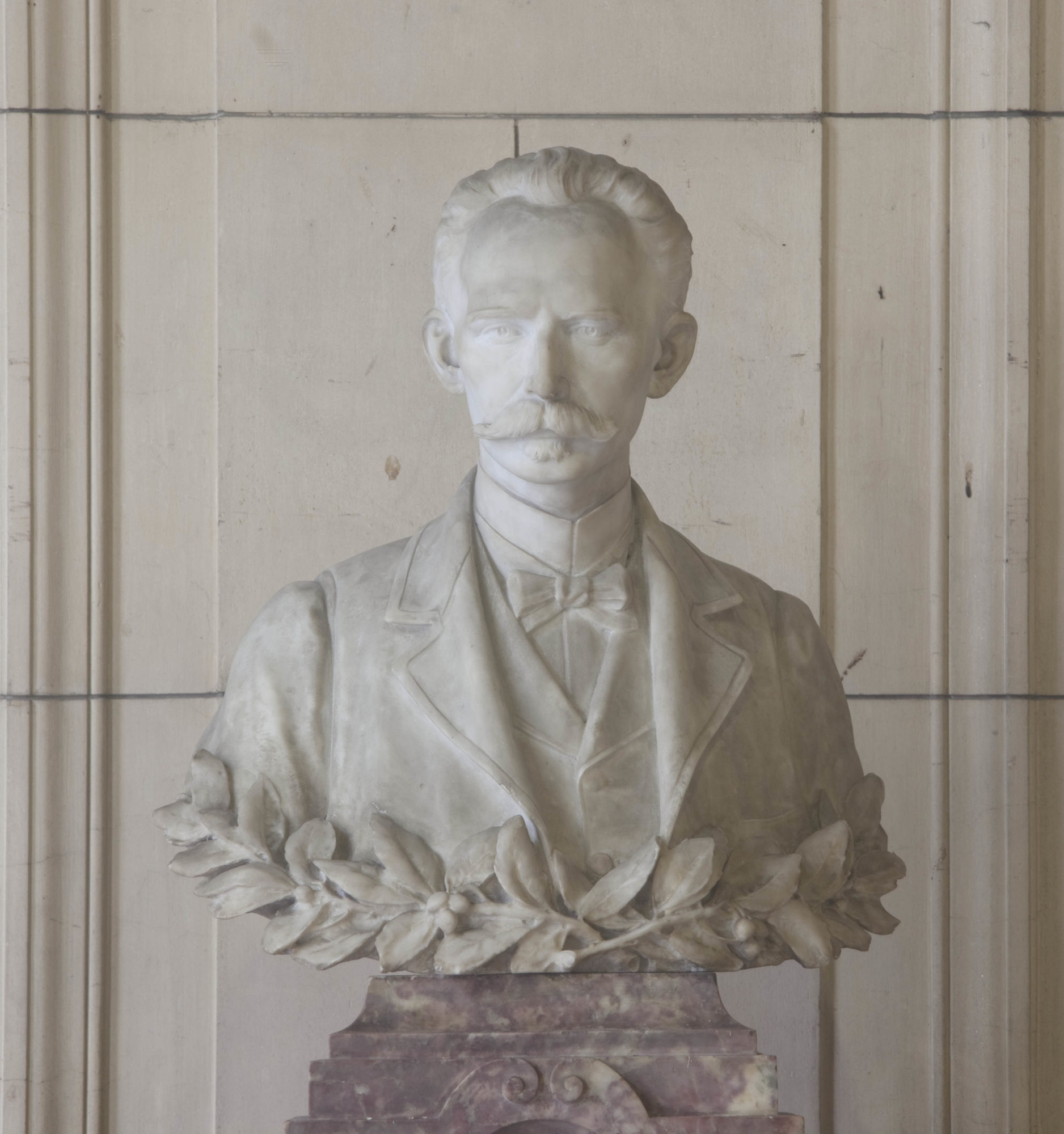

José Martí LC-DIG-highsm-06416

Why should we care about this brief transatlantic encounter during the mid 1860s? Most immediately, one is struck by the contrast between the civility of the exchange and its extreme unlikeliness in today’s political climate. More substantially, there are three reasons why these documents are significant. First, the correspondence reminds us of the tremendous importance of London as a refuge for exiled intellectuals and dissenters. It served as a magnet for all of those exiled revolutionaries, dreamers, and internationalists. This role would be taken up by New York City from the late nineteenth century onwards. Just think of Cuban nationalist José Martí during the 1880s, Marxist Leon Trotsky in the early twentieth century, and Black internationalist Marcus Garvey in post World War I. Second, the Address and Adams’s reply with their emphasis on slavery as being central to the conflict makes one wonder what exactly professional historians have been debating concerning Civil War causation over the past 150 years? Are we just keeping ourselves employed or is there a more insidious reason why generations of American historians have offered every other explanation—states’ rights, bumbling politicians, ambitious politicians, industry versus agriculture, and so forth—except the one that was pretty evident to contemporaries?

The denial of freedom simply does not comport with a nationalist narrative of natural rights and liberty for all. Third, and most importantly, these two documents illustrate the international dimensions of the American Civil War. Most Americans—together with interested outsiders—see this fascinating era primarily in nationalist terms. It was a war that pitted Americans against each other. In contrast, the IWMA saw the conflict as a historical watershed with global ramifications while the U.S. administration recognized the cause of humankind. Indeed, in contrast to Lincoln’s famous expression in his 1863 Address, the world very much took note of what was done at this time.

Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie teaches at Howard University.