An Interview with Gerald J. Prokopowicz

An Interview with Gerald J. Prokopowicz

Jonathan W. White

Gerald J. Prokopowicz is professor of history at East Carolina University and a longtime member of The Lincoln Forum Advisory Board. A highly sought-after public speaker and battlefield tour guide, Prokopowicz is perhaps best known as the host of the popular podcast Civil War Talk Radio, which can be heard on Voice America, Apple podcasts, and other platforms—and which began its twentieth season in August! He is the author of two books: All for the Regiment: The Army of the Ohio, 1861–62 (University of North Carolina Press, 2001), and Did Lincoln Own Slaves? And Other Frequently Asked Questions about Abraham Lincoln (Pantheon, 2008). From 1996 to 2002 he was editor of Lincoln Lore. He joins us today to discuss his career in the Lincoln and Civil War fields.

JW: You practiced law for several years in Chicago after attending the University of Michigan for both undergrad and law school. What led you to leave that career and to pursue graduate work in history?

GP: History was always my first interest. When I was growing up, I was surrounded by adults who had participated in World War II. My grandfather had fought in World War I. So when I was a boy, playing army in the backyard with my friends, we all assumed that we would one day end up taking part in World War III. We watched “Combat” with Vic Morrow on TV and played with GI Joe. The kid who wasn’t interested in WWII history was the exception.

The Civil War was another story. I knew little about it until my family drove from Michigan to Washington, DC, to visit friends when I was in 4th grade. My parents weren’t history or Civil War buffs, but on the way back, they decided to detour to Antietam. My two younger brothers had fun playing on the cannons and climbing the observation tower, but I was transformed by the experience. To look at photographs of the Dunker Church and the Bloody Lane in the visitor center and then go outside and see those places right there was incredible. It was November when we were there, as practically the only visitors on the field, but I felt like there were a lot of ghosts present. I wanted to know more about them. Why had they come here to fight and die? How did they do it? And why?

In college I majored in history to pursue that interest, but I didn’t go to graduate school right away, because everyone in 1980 was saying that the job market for history professors was down but should improve once the GI Bill generation retired. I decided to go to law school instead, in order to be able to make a living. I spent a few years practicing commercial real estate in Chicago, representing developers who were building new strip malls along Cicero Avenue. It wasn’t very fulfilling work. I finally figured that the developers could get along without my expertise, and since I was still deeply interested in Civil War-era history, I decided to apply to a half dozen of the most selective history programs I could find, with the thought that if I could get into one of those, I might have a chance of becoming a professor someday, even with the job market as it was.

JW: What was it like to work with David Herbert Donald as your dissertation advisor?

GP: It was a wonderful experience. He was a great mentor and an extremely dedicated teacher. He would return thesis chapter drafts with more comments in the margin than there was text on the page. He was also very patient with me, more I’m sure than I deserved. Over the years, I’ve met people in the field who mentioned Professor Donald’s famous temper, but in eight years working under him, I never saw it displayed. One time I wrote a research assignment for his biography of Abraham Lincoln, and I didn’t do it the way he expected. He wasn’t happy, but instead of raising his voice, he just spoke quietly in his Mississippi accent, sort of like the way Martin Sheen as Robert E. Lee talks to Jeb Stuart in the Gettysburg movie: “Well, Gerry, this is not really what I expected.” It was just like, “Well, General Stuart, you are here at last,” as Lee supposedly said, and it was equally devastating.

But what I more often remember about him was how generous he was with his time. He set an example that I try to follow with my own graduate students, not always successfully. Seeing how much help they need makes me painfully aware of what a burden my classmates and I must have been for Professor Donald, and of how much I owe him for whatever I’ve been able to accomplish as a historian.

JW: Your first job out of graduate school was at The Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne. How did you wind up there, and what impact did it have on your career?

GP: I have Professor Donald to thank for that first job as well. A representative from the museum contacted him after Mark E. Neely Jr. left that position when he won the Pulitzer Prize for The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. As a fresh ABD [“all but dissertation”], still finishing my thesis, I couldn’t pretend to fill Mark’s shoes, but fortunately the people running The Lincoln Museum were willing to take a chance on me. Up to that time, I had never even thought about practicing history in a museum, but as of 1993 the market for tenure-track historians was no better than a decade earlier, so I was happy to get any kind of history-related job.

As it turned out, the job exceeded my expectations. The Lincoln Museum, which was founded in 1928 by Louis Warren as part of what became the Lincoln National Corporation, had an extraordinary collection of Lincoln-related artwork, documents, books, and artifacts. Better still, Lincoln National had just committed $6 million to creating a new home for the museum in their headquarters building in downtown Fort Wayne, Indiana. My first two years there were spent working on the design and construction of the new museum. I learned on-the-job about exhibit design, label writing, artifact acquisition and conservation, fundraising, education, community outreach, docent training, and all the other aspects of building and running a major museum. I hadn’t studied any of those things in grad school, but I got to work with some very talented professionals. Our bosses at Lincoln National originally thought that we could complete the project in a month, but fortunately they consulted with a panel of museum professionals from around the country who told them that it would take a minimum of two years. The bosses backed down and gave us a year and a half, which led to some long hours, but we got the museum open on time and on budget. Between 40,000 and 50,000 people visited the museum every year after that, until it was closed in 2008. It’s gratifying to have participated in a project that was viewed by more than half a million people, many more than will ever read my books or listen to my podcasts.

JW: In 2001, you invited Lerone Bennett to speak at the museum. What was that experience like?

GP: One of my responsibilities at the museum was to help organize the annual R. Gerald McMurtry Lecture, which has hosted many of the giants of Lincoln history. My first choice, in 1995, was to invite David Herbert Donald, who had just published Lincoln to national acclaim. In contrast, in 2000 Lerone Bennett published Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream and upset a lot of people. Bennett pointed out that historians traditionally excused anything Abraham Lincoln ever said that sounded racially inappropriate to twentieth-century ears by saying that he was just being a practical politician, appeasing the deep racism of his nineteenth-century voters. When Lincoln said something more virtuous, like, “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong,” the same historians said that those were Lincoln’s true feelings. Bennett asked, what if the opposite were true? He reversed these interpretations to portray a Lincoln whose real commitment was to white supremacy and who only spoke for freedom and equality as a cynical political expedient. It reminded me of Bizarro, the evil clone of Superman. I thought then, and still think, that Bennett’s interpretation was wrong, but it was fascinating to see how consistently he stayed with the original documents, just reading each one 180 degrees from the way everyone else had. It was an argument that exposed the traditional bias in Lincoln interpretation and opened the door for other scholars to take more complex and nuanced views of Lincoln and race, as Brian Dirck would do ten years later in Abraham Lincoln and White America. I didn’t agree with Bennett’s conclusions, but I thought that his work was important enough to merit a hearing in a venue like the McMurtry Lecture that had always featured more mainstream speakers.

The lecture was supposed to happen in September 2001, but a week or so after September 11th, Lerone called me to talk about what had just happened. He said that the country was now in a different place and national unity was important. He didn’t think that it was the right time for his iconoclastic approach to an American hero like Lincoln, so we rescheduled the lecture for late October.

When it finally happened, the lecture was a great success. We had one of the largest turnouts for any McMurtry Lecture during my time at the museum, and by far the most diverse audience ever, generationally as well as racially. I did receive a little bit of negative feedback, presumably from people uncomfortable with Bennett’s challenge to their views of Lincoln, but my only regret was that I was not able to schedule more events with such provocative speakers.

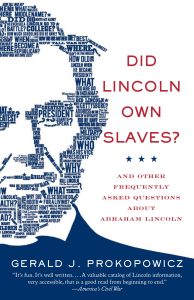

JW: Tell us about Did Lincoln Own Slaves? What led you to write that book, and what did you enjoy most about the process of conceptualizing and writing it?

GP: One of my favorite things about working at The Lincoln Museum was talking to visitors and giving presentations to non-academic audiences. I especially enjoyed the question-and-answer sessions that came at the end of talks. It was fascinating to me to see what kinds of things people really wanted to know about the past, and to see how sharply their interests often differed from those of academic historians. Since grad school, I’ve posted on my office wall a quote attributed to Leo Tolstoy: “Historians are like deaf people who go on answering questions no one has asked them.” Sometimes we do need to think of and answer questions that no one else has yet thought to ask, but there’s a real danger of irrelevance if those are the only questions that historians answer. If we don’t stop and listen to the questions people really are asking, then people are going to get their answers somewhere else.

I left The Lincoln Museum in 2003 to see if I could finally live the dream of becoming a history professor. Unfortunately, the job market had gotten no better, at least not for Civil War history professors. As I was looking at job ads, though, I kept seeing positions for people who could teach something called “public history,” which I had never heard of. When I got around to researching what it was, I discovered that it was what I’d been doing for the past nine years. That opened up some new opportunities that led to my current position teaching American history, military history, and public history at East Carolina University.

Teaching was every bit as fulfilling as I had hoped, but I didn’t want to lose my connection to the world of practical public history or forget all the fascinating question-and-answer sessions about Abraham Lincoln that had been part of my work at The Lincoln Museum. That’s why I wrote Did Lincoln Own Slaves? And Other Frequently Asked Questions about Abraham Lincoln, formatted as a prolonged question-and-answer session. The questions were a way to recognize the importance of the public’s particular interests, while the annotated answers were intended to summarize the best of serious Lincoln scholarship.

JW: Civil War Talk Radio is one of my favorite podcasts—both as a listener and a guest. When you began doing the show in 2004, it seems you were on the cutting edge of what is now known as digital humanities. What led you to start the program, and how has doing the show changed over the years?

GP: The show was started as part of something called World Talk Radio, based in Phoenix. The entrepreneurs who created it imagined that there was a market for what they called “internet radio.” Their expectation was that listeners would tune in to their computers to hear scheduled live webcasts, the way people used to listen to radio programs in the 1930s. One program idea they had was for a show about the Civil War, something they called “Civil War Talk Radio.” Through a friend of a friend, I was asked to do a sample program, which I did. They didn’t have anyone lined up for the next week’s show, so I did that one too, and the next six hundred after that. It wasn’t anyone’s plan.

As it turned out, almost no one listened to the show when it went out on the internet live. Few people listen to the live webcast today, maybe twenty in a good week. But the shows were posted in an archive online after they were produced, and it soon turned out that lots of people were downloading the archived recordings so they could listen on their iPods when they were washing dishes or mowing the lawn, instead of listening live. Civil War Talk Radio was essentially podcasting in 2004, making it today one of the oldest continuously running podcasts.

In terms of the format of the program, very little has changed over the past twenty years. The idea has always been to find guests who have done interesting work in Civil War history, as authors, curators, preservationists, musicians, or through any other form of public history, and then to let them have time to develop their ideas over the course of an in-depth interview. Despite the name of the program, it has never sounded anything like typical “talk radio.” The guests get to do most of the talking, there are no callers into the show, and the host doesn’t interrupt or rant and rave about anything. Well, actually, I do sometimes rave about topics of interest to me during the first ten minutes of each program, but that’s before the guest comes on. Sometimes I’ll talk about current issues in Civil War history, but more frequently it will be about administrative nonsense at East Carolina University, or the games of my daughters’ soccer teams (back when they were kids), or the ups and downs of University of Michigan sports. Some listeners have written in to say that they enjoy the personal connection that they feel from hearing about whatever’s on my mind each week. Others have no use for the monologue, but that’s what the fast forward button is for.

JW: Listeners can learn more about Civil War Talk Radio at www.impedimentsofwar.org/. How did you come up with that URL? And what can readers of Lincoln Lore find there?

GP: Like the name of the show, “Civil War Talk Radio,” the name of the website “Impediments of War” wasn’t my idea. The website was created and is maintained by Mark Gaffney, whom I’ve never met. He created it as a fan website many years ago and I’ve been happy to work with him. I send him the schedule of upcoming shows as soon as I have commitments from guests, and he updates the website and Facebook page for Civil War Talk Radio. Occasionally I’ll send him a box of books that I’ve received from publishers that I haven’t been able to use on the show, as a gesture of thanks for all that he does, but other than that, Impediments of War is purely a labor of love on his part, and one for which I’m very grateful.

JW: Over the course of nineteen seasons, you’ve conducted more than 600 hours of interviews. Looking back over those hundreds of episodes, do you have any that stand out?

GP: There have been so many interesting guests that I could never pick a favorite show, but there have been some that stand out in memory for other reasons. One of them was an interview with two sisters who were recent college graduates and authors of a book called Badass Civil War Beards. As a lark they had been writing a blog about the beards worn by Civil War generals, the sort of whimsical thing that you find on the internet when looking for something else, and apparently the blog was popular enough that they decided to compile their work into a book. I get messages from authors’ publicists all the time, but theirs was relentless in her effort to get them on the show. I wasn’t sure that I could put together 50 minutes’ worth of questions about beards, but the publicist wouldn’t take no for an answer, so I asked the listeners what they thought of the topic, and by a substantial margin they said they wanted me to do the interview. It turned out that the two co-authors were delightful people who unfortunately did not know a great deal about the Civil War, other than what they had picked up while compiling amusing photographs of bearded generals. But they were also close in age to my own two daughters, and I desperately wanted to avoid embarrassing them. What could I ask them that wouldn’t expose their lack of knowledge? Fortunately, some of the listeners who had voted for the topic had included questions that they wanted me to ask, so I turned to those. Some of the questions went well beyond the frivolous nature of the book, dealing with issues like masculinity and self-image, but at least they didn’t require any detailed knowledge of Civil War history and gave the program a semblance of meaning. One way or another, we got through the hour without any prolonged awkward silences. Most weeks, at the end of the show the guest and I are both a little surprised by how quickly the time has flown by, but the beard book interview was definitely the longest fifty minutes I’ve ever spent behind a microphone.

JW: Have there ever been any fireworks on the show? Any books where you challenged the author’s views?

GP: Fireworks? No. I’m pretty sure that in 20 years of recording the show I’ve never raised my voice when speaking with a guest. If someone is looking for drama in the presentation, Civil War Talk Radio will disappoint. But that’s not to say that I agree with everything I hear. I read every book in advance and make notes whenever I find something that I think merits some pushback. Gary Gallagher, who has been on the show several times, is one of my favorite guests, and he and I definitely don’t agree on some issues, but the kind of dialogue that results is, I hope, the kind that provokes thought instead of triggering an emotional response.

On a few occasions I’ve had guests whose work I thought deserved some serious criticism. Normally, I don’t invite someone onto the show unless I think that the listeners will find their work valuable. I don’t want to waste their time or mine talking about books that are neither interesting nor informative, but once in a while I’ll schedule an interview about a book that looks promising but turns out to have little to recommend it. Maybe the author doesn’t have anything original to say, or maybe they’re just not a very good writer. When that happens, I don’t spend the hour confronting the author with their work’s flaws, but I will usually probe a little to see if they recognize where their work might not measure up. Not long ago I spoke with a bestselling author who was unwilling or unable to recognize the distinction between his work as a journalist who spent a year or two reading secondary sources in order to write an engaging but superficial narrative, and the work of a professional historian who spends a career steeped in primary sources to create works of original archival scholarship. I wasn’t impressed by the guest’s lack of self-awareness, but I figured that I had pursued the point far enough for the listeners to draw their own conclusions, so we moved on, and no fireworks ensued.

Actual talk radio is nothing but fireworks. I keep my car radio tuned to the station that plays East Carolina University sports, and if I turn it on when there’s no game, what I usually hear is “sports talk radio,” which as far as I can tell consists of two or more men talking loudly, interrupting one another, and delivering their opinions with an attitude of absolute certainty that implies that only an idiot could disagree. The content of their opinions is irrelevant. I’m pretty sure that they don’t actually care if LeBron or Jordan is the greatest player of all time, they just take up opposing views so they can generate the necessary verbal fireworks. It’s the audio equivalent of professional wrestling, and it’s the opposite of what I try to do on Civil War Talk Radio.

JW: You really have your finger on the pulse of Civil War scholarship. (I’ve always been impressed by the wide variety of guests you have on your program.) What is your sense of the state of the field?

GP: I’m continuously impressed by the way that scholars keep finding new and unexpected approaches to the study of the Civil War era. Over the last twenty years, the so-called “Dark Turn” shifted research toward aspects of the war that were previously considered inappropriate, or too arcane, or that simply had never been thought of, but which now dovetail with the interests of many contemporary readers. The expansion of environmental history is one example. The growth of interest in guerrilla warfare, or the fighting in the Far West, are two others.

Your book, Midnight in America: Darkness, Sleep, and Dreams during the Civil War, looks at literally half of the Civil War era that historians have largely ignored because the sun was down. It’s an extraordinary conceptual leap.

I also see scholars using new technological tools as well as intellectual ones to expand what we know about the Civil War. The recent identification of the place Lincoln was standing when he delivered the Gettysburg Address, for example, answers a long-asked question that isn’t itself critical, but the use of 3D visualization software to triangulate well-known photographs and draw new information out of them is potentially the biggest step forward in Civil War photographic research since William Frassanito’s work in the 1970s. [Editor’s Note: Christopher Oakley originally presented his research on the location of the speaker’s platform at The Lincoln Forum in November 2022. Unbeknownst to Gerry, the Summer 2023 issue of Lincoln Lore, which contains Oakley’s article on this subject, was being printed at the very moment Gerry was answering this question.]

The intersection of Civil War studies and contemporary politics is another place where I see the field likely to evolve, perhaps in unpredictable directions. The controversy over the past few years regarding how we remember the Civil War and how we have memorialized it over the past century and a half has advanced the quality of discourse about public history dramatically. Ordinary people didn’t think much about monuments twenty years ago, and when they did, they treated them as though they had sprung out of the earth. But now we see vigorous debate over both the subjects of Civil War memorials and the motives and meanings of the generations that put them up. I hope that scholars will capitalize on this interest to keep educating the public on the topic.

Perhaps even more important, the value of evidence and the possibility of reaching conclusions about past events have been challenged by the evolution (or devolution) of political rhetoric and the ability of anyone to communicate to wide audiences via the internet. I see the discipline of history, not just Civil War-era history but the entire field, standing as a bulwark against the notion that anything can be true if you say it’s true often enough and to enough people. As I tell my students over and over, we are practitioners of an evidence-based discipline. We can disagree as to interpretation, but we share a common respect for historical evidence as the common ground upon which we can judge one another’s interpretations. Thus far, Civil War studies have largely maintained their integrity in this regard. We disagree amongst ourselves all the time, but we support our arguments with reference to historical sources, not by trying to drown out contrary interpretations with mere repetition. If Civil War Talk Radio makes any contribution to the field, it is in promoting this kind of evidence-based discourse.

JW: What are you working on now?

GP: Just the next season of Civil War Talk Radio at the moment. I’m planning to get back to research and writing as I approach retirement, but that I hope is still a few years away.

JW: Thank you so much for joining us today!

GP: Thank you for the invitation. I’m pleased that Lincoln Lore is in such good editorial hands!