The Unhappy Fate of Fitz John Porter

The Unhappy Fate of Fitz John Porter

By Allen Guelzo

The American Civil War was a political war. That should not matter hugely to those of us who study the art of command in the war, since it is one of the basic tenets of the American system of governance that the military remains in strict subordination to civilian authority, and leads apolitical lives in uniform. Military leaders who have forgotten the strictness of that subordination have, from Andrew Jackson to Stanley McChrystal, been reminded of it in some very unpleasant ways. But the American Civil War was different. It forced political decisions on American soldiers at the very beginning, and the gaping divisions those decisions created fostered an atmosphere of political mistrust and conflict that inhabited every nook and cranny of military command.

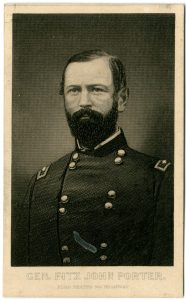

This is not the way we would prefer to remember the Civil War; we would rather think of it strictly in strategic, tactical or logistical terms, as we usually do with the great World Wars. But we cannot. George McClellan, perhaps the most politically insubordinate general in American history, will not allow us, nor will the political leadership he railed against—starting with Abraham Lincoln. And no one offers a more agonizing example of how politics elbowed its way into the art of command in the Civil War than Major General Fitz John Porter, whose court-martial and dismissal for his conduct at the Second Battle of Bull Run offers a painful example of the risks and follies of soldiering in a political war.

Fitz John Porter was the child of a military family, although it was not an association from which he derived much profit. His grandfather had commanded privateers in the American Revolution, but his reputation was clouded in the postwar years by rumors “to his prejudice . . . for keeping a Public house of Ill fame in Boston” and losing “a ship in such a way as to induce suspicions of his integrity.”[1] His father, David Porter, yet another naval officer, managed to wreck his first command, and his career was plagued by quarrels, mismanagement, and alcoholism. His wife, Eliza Clark Porter, was the real head of the household, and it was Eliza Porter who was chiefly responsible for placing her second child, Fitz John Porter, as a cadet in the U.S. Military Academy in 1841, graduating 8th in his class in 1845, in the same year as Charles Stone (another victim of Civil War politics) and a year ahead of George McClellan.

Porter was part of Winfield Scott’s great inland march to Mexico City in the Mexican War, earning two brevet promotions to captain and major, and returned to West Point as an assistant professor and temporarily (under the superintendency of Robert E. Lee in the 1850s) post adjutant. Oliver Otis Howard remembered Porter’s conduct as precise and competent in managing “the whole corps of cadets” on the parade ground, “and I was exceedingly pleased with his military bearing.” But if Porter was competent, he was also dull. His wife, Harriet, remarked that Porter was “shy and retiring,” and his daughter would recall that she had never once heard her father laugh.[2] When Jefferson Davis, as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, created two new light cavalry regiments in 1855, Porter was passed over for a command in them, and only the urgent intercession of Eliza Clark Porter won her son a belated posting to the West. Even then, it was only as adjutant to the Department of the West at Ft. Leavenworth, and the only serious action he saw was as adjutant for Albert Sidney Johnston’s bloodless expedition against Mormon Utah.

The outbreak of the secession troubles after Lincoln’s election saw Porter buzzing from pillar to post: reporting to the War Department on a flying visit to Charleston in November 1860, another flying visit to the Gulf coast in February 1861, to supervise the extraction of seven companies of U.S. troops from secessionist Texas, trying to manage the forwarding of Pennsylvania militia and the 2nd U.S. Cavalry to Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in April, then as adjutant to Major General Robert Patterson’s half-hearted advance into Virginia in July.[3]

Patterson’s failure and subsequent shelving might have put a period to Porter’s Civil War career. But on August 1, 1861, Porter wrote directly to George McClellan, who had just been called from his successful campaign in western Virginia to command the dispirited Union forces around Washington, D.C. “I can be of much use and render the country essential services,” Porter pleaded. “I cannot bear” to “see my companions, my juniors, rising to distinction and position, while I must plod away in a beaten and sandy track.”[4] It is not clear exactly when Porter first became an intimate of McClellan’s—there is nothing in their student record to suggest any connection, and only one stray reference to Porter in McClellan’s Mexican War papers, but they did share quarters at West Point when both were on station there in 1850. Yet, they evidently knew each other well enough in the small confines of the pre-war Army that Porter could urge McClellan to resign from his civilian job in 1861 and re-enter the service, while McClellan would remember asking for Porter as an adjutant when he was first given command of the Department of the Ohio.[5] The plea worked. On August 7th, Porter found himself commissioned as colonel of the 15th U.S. Infantry; three days later, he was a brigadier general of volunteers. By the fall, he was commanding one of McClellan’s divisions.

It was not clear, either, what Porter’s politics were—at first. Like so much of the old Army, Porter cultivated a studied distance from politics, partly from the principle of subordination to civilian authority, but partly from the example of what happened to soldiers like Winfield Scott when they crossed politicians like President James Polk. But the outbreak of the Civil War brought a tremendous influx of new volunteer officers into the service, in command of the new volunteer regiments. Their appointments were the plaything of Northern state governors and they often made little secret of their hostility to slavery and the Democratic Party. When Porter discovered that one of his volunteer colonels, John Pickell of the 13th New York, had assisted a slave in taking flight from his master, Porter ordered the slave expelled from his camps. “Slavery existed” by law, Porter explained (as though this was supposed to deal with any objections), “and we were in a slave state and the owner was entitled to his servant and no officer had the right to use his rank to take property from a loyal” owner.[6]

This tone-deafness to the volatility of the slavery question might have stymied any further advancement for Porter in what became known as the Army of the Potomac, had not the Army’s commander been George McClellan, who suffered from more than a little tone-deafness of his own on the subject. Instead, Porter grew closer and more confiding to McClellan, and McClellan played Porter more and more as a favorite. McClellan cultivated New York Democratic politicians, and encouraged Porter to do likewise; he also cultivated New York Democratic newspapermen like Manton Marble of the New York World, and—unwisely—Porter also did so.

None of this went unnoticed in Congress or the Executive Mansion. President Lincoln warned McClellan in May that it had become all-too-well known that “you consult and communicate with nobody but General Fitz John Porter.”[7] When Lincoln mandated a reorganization of the Army of the Potomac into French-model corps d’armée, Porter’s name was not among the division officers promoted to corps command.

Not that this seemed to matter once the Army of the Potomac finally embarked on its great Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862. McClellan appointed Fitz John Porter director of the siege of Yorktown, and with his usual methodical precision, “the operations were conducted with skill.” But McClellan’s favoritism infuriated pro-administration officers, including Porter’s own corps commander, Samuel Heintzelman, who groused that “McClellan is giving great dissatisfaction in this Army, particularly about Gen. Porter.” No matter: on May 18th, McClellan decided to subdivide the existing corps of the Army of the Potomac, and handed one of the new commands, the Fifth Corps, to Porter.[8]

The Peninsula Campaign did not end well for McClellan, for whom the Seven Days’ Battles in June concluded with the Army of the Potomac backed into a tight perimeter around Harrison’s Landing on the James River. Porter, however, did remarkably well in corps command, “gallantly standing off” a savage attack by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Gaines Mill on June 27th, and mowing down Lee’s Confederates from the commanding height of Malvern Hill on July 1st. McClellan evidently planned to cross to the south side of the James and, at Porter’s urging, renew his advance.[9] Lincoln was having nothing of it. Lincoln was clearly offended during a visit to Harrison’s Landing on July 8th by McClellan’s arrogant declaration that the president must abandon any thought of emancipating Southern slaves lest the Army of the Potomac disintegrate—as though McClellan would bear no responsibility for such disintegration. Two weeks later, Lincoln appointed a new general-in-chief, Henry Wager Halleck, to put a bit in McClellan’s mouth.

McClellan was too much the darling of the Democratic opposition for Lincoln to risk an outright dismissal. Instead, in late June, Lincoln created a new Army of Virginia (from pieces of units that had been pummeled that spring in the Shenandoah Valley by “Stonewall” Jackson) under Major General John Pope. In August he ordered the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac piece-by-piece from the Peninsula, and fed those pieces into the structure of the Army of Virginia. Pope’s official qualifications for command in the east rose from his success that April in forcing the surrender of the Confederate post at Island No. 10 in the Mississippi River, which pried open the river to federal gunboats as far south as Vicksburg. But his real qualifications were political: the son of the one-time presiding judge over Lincoln’s old court circuit in Illinois and one of the four officers who formed Lincoln’s personal bodyguard for his inaugural trip to Washington, Pope was solidly anti-slavery and hence regarded as “the Coming Man . . . of the army.”[10]

John Pope was everything McClellan was not, and Porter did not mind saying so. In late July, after Pope had assumed command of the Army of Virginia, Porter described him as “what the military world has long known, an ass…and will reflect no credit on Mr. Lincoln.” As July turned to August, Porter turned up the heat in his letters, describing Pope to New York World editor Manton Marble as a “fool,” and—still worse—wishing that McClellan “was in Washington to rid us of [the] incumbents ruining our country.” By the time Porter and the Fifth Corps had, by road, boat, and rail, reported to Pope on August 27th, Porter was earnestly “wishing myself away from” Pope “with all our old Army of the Potomac,” and begging Ambrose Burnside, “if you can get me away, please do so.”[11]

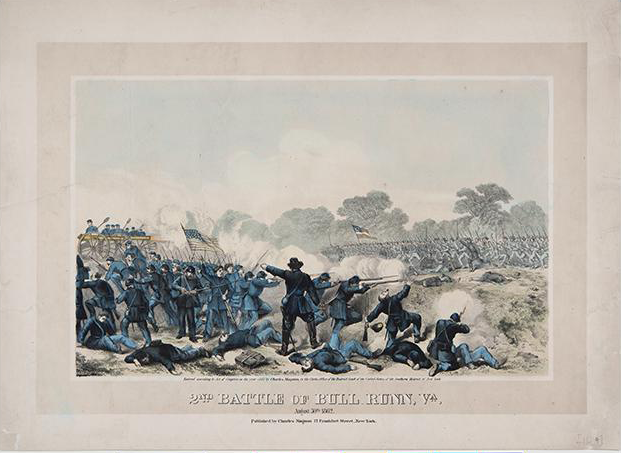

Porter’s opinion of Pope had not been improved by the beating which elements of the Army of Virginia received at the hands of “Stonewall” Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9th, nor by the disastrous raid Jackson and J. E. B. Stuart staged on Pope’s communications and supplies at Manassas Junction on August 27th. The next day, Jackson drew off to the old Bull Run battlefield, luring Pope after him under the delusion that Jackson’s portion of the Army of Northern Virginia was sufficiently isolated that Pope’s army could destroy it. Marching through the ruins of Manassas Junction, Porter and the Fifth Corps were ordered to take position southwest of the Sudley Springs-Warrenton Turnpike crossroads (at the center of the 1861 battlefield), under the impression that Porter would be able to turn Jackson’s right flank. But the orders Pope issued for Porter’s movement “at once on the enemy’s right flank” on August 29th were vague, confusing, and—above all—late (the order for Porter to attack Jackson was written by Pope at 4:30 in the afternoon, but did not reach Porter until 6:30, when dusk was coming on). Porter also was beginning to realize what Pope did not: that the balance of the Army of Northern Virginia, under James Longstreet, was moving into position on Jackson’s right, and ready to strike a devastating blow at Pope. Apprehensive, Porter ordered a pull-back of his skirmishers.[12]

A copy of Porter’s pull-back order crossed Pope’s 4:30 attack order, and Pope promptly sat down at 8:50 that night and wrote out yet another order, demanding that Porter appear before him for an explanation. Porter did the next morning, August 30th, and tried to convince Pope of the trap waiting to spring on him. Pope would hear nothing of it. “I am positive, that at 5 o’clock on the afternoon of the 29th General Porter had in his front no considerable body of the enemy,” Pope later insisted. “Every indication during the night of the 29th and up to 10 o’clock on the morning of the of the 30th pointed to the retreat of the enemy from our front.”[13] He could not have been more wrong. “No orders of this campaign,” Porter later remarked, “more erroneously stated the attitude of the opposing forces or led to more serious disaster.” That afternoon, Longstreet’s “twenty-five thousand braves moved in line by a single impulse” over the Fifth Corps and everything else that composed Pope’s left flank; by that evening, Longstreet and Jackson had crushed the Army of Virginia and sent it fleeing in disarray toward Washington.[14]

Pope, his army a shambles, at once flailed around for excuses, and found his principal target in Porter. “I think it my duty to call your attention to the unsoldierly and dangerous conduct” manifested “by officers of high rank,” Pope wrote to Henry Halleck early on September 1st, and he was particularly incensed at “one commander of a corps who . . . fell back to Manassas without a fight.”[15] There was no mystery about who Pope had in mind. Pope had his acolytes in the Army of Virginia fully as much as McClellan had in the Army of the Potomac. Robert Milroy, an Indiana abolitionist who commanded one of Pope’s brigades, exploded that the defeat at Bull Run was causedby the “treachery and incompetency . . . of the Generals in the interest of McClellan,” and “especially was Gen. Fitz John Porter most roundly berated.” George Templeton Strong, the New York lawyer and treasurer of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, hinted at what would emerge as a continuing theme, that “McClellan, F. J. Porter and others” had long been “personally friends, allies and political congeners” with “Jackson, Lee and Joe Johnston,” and were looking for an opportunity to “agree on some compromise or adjustment, turn out Lincoln and his ‘Black Republicans’ and use their respective armies to enforce their decision north and South.” The New-York Tribune was more direct in who it fingered for blame. “I was with Pope’s army as a correspondent,” wrote Nathaniel Paige, and “Porter did not intend to help Pope win that battle.”[16]

Pope submitted a preliminary report on September 4th. The next day, Lincoln suspended Porter from command and ordered the convening of a court of inquiry into Porter’s conduct at Bull Run.[17]

That should have spelled the end of Porter’s military career. It didn’t, because the crisis that prevailed in the wake of Pope’s Bull Run disaster was so grave that Lincoln felt he had no choice but to recall George McClellan, first to supervise the defense of Washington on September 2nd and then on September 6th to resume direction of the Army of the Potomac, with all of Pope’s fragments securely under his control. Lincoln explained this volte-face as a recognition that McClellan “is a good engineer . . . [and] there is no better organizer,” and “he can be trusted to act on the defensive.” But behind that rationale was Lincoln’s fear that although “there has been a design, a purpose in breaking down Pope . . . there is no remedy at present. McClellan has the army with him.”[18] And with the restoration of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan demanded—and got—the re-instatement of Porter, first for command of the capital fortifications on the south side of the District, and then for the Fifth Corps again on September 11th.

Lee had no intention of challenging the Washington fortifications. Instead, he crossed into Maryland in hopes of rallying slaveholding Marylanders to take their state out of the Union, and then planning to venture brazenly into Pennsylvania, where he could inflict political damage on the Northern will to continue the war. The good news for Porter was that McClellan succeeded beyond almost every expectation in frustrating those plans. In just two weeks’ time, McClellan rallied a beaten and disorganized army’s morale, resupplied and re-organized it with new leadership at the corps level, integrated an ill-trained and ill-prepared wave of recruits into his existing forces, and then set off in pursuit of Lee’s Confederates through Maryland. McClellan, in fact, moved so fast that Porter only caught up with McClellan on September 14th, with two divisions under General George Morell and General George Sykes.[19] On that day, McClellan won a significant victory over Lee at South Mountain, and then won (at least) a victory at Antietam three days later.

The bad news was that none of this was sufficient to dispel the clouds of mistrust generated by Second Bull Run, over either McClellan or Porter. McClellan fell under immediate suspicion in Washington for not pursuing Lee after Antietam with sufficient verve, as well as for showing noticeably little enthusiasm for Lincoln’s issuance of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22nd. If anything, Porter (who was even more explicit in his criticism of the Proclamation to Manton Marble on September 30th) fared even worse. Throughout the entire day at Antietam, McClellan held Porter and the Fifth Corps in reserve at his headquarters at the Pry House, and the optics of that reserve looked like nothing so much as a conspiratorial repeat of Second Bull Run. David Strother, a staff officer, noticed that Porter spent the day “with a telescope,” surveying the battlefield and speaking to McClellan “in words so low-toned and brief that the nearest by-standers had but little benefit from them,” as though the battle was “a drawing-room ceremony.”[20]

This arrangement was not as palsied as it looked. Through the day, pieces of the Fifth Corps were detached to prop up General Edwin Sumner’s Second Corps, to support a tentative movement across the Middle Bridge over the Antietam Creek, and to cover the army’s trains and reserve artillery, so, that by the close of the fighting, Porter’s command was “not then 4000 strong” and perhaps “but little over three thousand men.”[21] Nevertheless, hostile newspaper correspondents saw only typical Porter inaction. When “Burnside is pressed,” wrote the New-York Tribune’s correspondent, George Smalley, McClellan turned to Porter, whose “15,000 troops are lying . . . fresh and only impatient to share in the fight.” But Porter only “slowly shakes his head and one may believe that the same thought is passing through the minds of both generals. ‘They are the only reserves of the army; they cannot be spared.” Even the Times of London’s correspondent, Francis Charles Lawley, sang the same damning song, that “General Fitz John Porter, with 15,000 men in reserve” became “the only body of men on the Federal side which was not engaged.”[22] Nor did it help Porter that, on September 20th, the Fifth Corps was given the job of treading on the retreating Confederates’ heels across the Potomac at Shepherdstown, only to receive a humiliating brush-back.[23]

This was only the beginning of sorrows for Porter. McClellan’s failure to chase Lee down after Antietam heated Lincoln’s ire to a hot pitch, and on November 7th, once past the danger line of the off-year congressional elections, Lincoln dismissed McClellan once and for all. McClellan bade his farewells to the Army of the Potomac on November 10th, and the uproar of protest nearly crossed the boundaries of mutiny. “As General McClellan passed along its front, whole regiments broke and flocked around him, and with tears and entreaties besought him not to leave them, but to say the word and they would soon settle matters in Washington.”

Porter did not imagine he would do any better—“You may soon expect to hear that my head is lopped,” he wrote to Manton Marble on November 9th—and he was right. Two days after McClellan’s departure, Porter was once again relieved of command of the Fifth Corps. “The troops gave proof of their grief in many ways at the loss of the honored and beloved commander, who had, by his heroic bravery in battle, and by his kindness of heart in camp, endeared himself to them,” remembered the historian of the Fifth Corps, William H. Powell. But there was nothing like the demonstrations that had tried to persuade McClellan to defy Lincoln’s orders. “We are not aware,” remarked the laconic chronicler of the Pennsylvania Reserve division, “of there being any particular amount of ‘weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth’ at the event.” The engines of the post-Bull Run court of inquiry began turning once more, and on November 17th Porter was placed under arrest and “confined to the limits of his hotel” in Washington. On November 25th, the inquiry was reconstituted as a court-martial. [24]

The court-martial required no crystal ball to predict its outcome. Porter was charged with nine violations of the Articles of War, all of them centering on his alleged disobedience of John Pope’s orders on August 29th and 30th. McClellan, called as a witness on January 2nd, testified to Porter’s “loyalty, efficiency and fidelity,” but from McClellan, those accolades were almost the kiss of death. When John Pope appeared as a witness, he was was so confident of himself that he declared that “had General Porter fallen upon the flank of the enemy” on the night of August 29th, “we should have destroyed the army of Jackson.” From there, it was only a short distance to the testimony of Pope’s aide, Thomas C. H. Smith, that he had been “certain that Fitz John Porter was a traitor,” and that Smith was ready to “shoot him that night, so far as any crime before God was concerned, if the law would allow me to do it.” The law did not, but it also did not prevent the court-martial from finding Porter guilty of all but two of the specifications on January 10th. Curiously, the New York Times had predicted that the trial would “unanimously” acquit “Gen. Porter of the charges brought against him,” and even the New-York Tribune conceded that “outside public opinion acquits the General.” But not the court. And above all, not Abraham Lincoln, who not only approved the verdict on January 21st (which dismissed Porter from the Army) but was convinced that Porter’s “disobedience of orders and his failure to go to Pope’s aid” at Bull Run had “occasioned our defeat and deprived us of a victory which would have terminated the war.” Lincoln told his confidante Leonard Swett that he had “read every word in that record, and I tell you Fitz John Porter is guilty and ought to be shot . . . He was willing the poor soldiers should die while he from sheer jealousy stood within hearing of the guns waiting for Pope to be whipped.” Porter’s inaction at Antietam only made matters worse, and Lincoln told his son, Robert, that “the case would have justified, in his opinion, a sentence of death.”[25]

Fitz John Porter set to work almost at once to obtain a reversal of the verdict, and his chief counsel at the court-martial, Reverdy Johnson, published a vigorous condemnation of the court-martial’s proceedings, raging that “a greater injustice was never done through the forms of a judicial proceeding, than was done by the sentence of the Court Martial in the case of that gallant officer.”[26] And indeed, the entire trial can only be read (and was so read by Emory Upton in 1879) as a kind of star-chamber proceeding in which Porter became the American version of Admiral Byng, pour encourager les autres who might show insufficient enthusiasm for emancipation. Wheeled into action on only two days’ notice, by a general (namely, John Pope) whom few people—even among those who condemned Porter—were unembarrassed enough to praise or promote, Porter may have been unimaginative in his decisions. But, those decisions were neither decisive in the outcome of Second Bull Run—that judgment belongs on Pope’s and Irvin McDowell’s heads—nor treasonous to the Union cause. And his supposedly baleful influence on McClellan at Antietam owes most of its force to the scandalous irresponsibility of the journalists who had already conceived a narrative to which Porter was made to fit.

It would, however, take years for Porter to get the re-hearing he demanded. He found employment in mining and civil engineering—even, in 1871, assuming the job of cleaning-up the corruption left behind by “Boss” Tweed as Commissioner of Public Works in New York City. It was not until 1878 that Porter’s case was finally re-opened by the War Department, and, even then, unburied partisanship denounced “General Porter’s conduct…at the second battle of Bull Run” as “essentially traitorous.” Jacob Dolson Cox, one of the rare abolitionist general officers in McClellan’s army (and who served as governor of Ohio immediately after the war), wrote a particularly vindictive review of the Porter case in 1882, which declared that Porter’s “disaffection to Pope had led him beyond the verge of criminal insubordination.” It was not until 1886 that President Grover Cleveland—the first Democrat president since the war—signed a bill restoring Porter to his original U.S. Army rank of colonel. Porter officially retired from the Army four days later. Weakened by the ravages of diabetes, he died on May 21, 1901.[27]

The unhappy fate of Fitz John Porter is a story of unfairness, even cruelty, meted out to a soldier whose only military crime had been the same myopia in the fog of war that afflicts all but the most acute possessors of the coup d’œil. It may be difficult to say more than that about him, too. Porter “departed…with the sincere regrets of all of his soldiers,” but not near-mutiny. His humiliation, recorded one Massachusetts soldier, was “enough to move a heart of stone,” but “by this time the old army had become a heart of stone,” and Porter did not move it much. He was neither a traitor nor an idol, nor was he (as Otto Eisenschiml wanted to portray him) “an American Dreyfus,” so, in the end, his condemnation says less about him than it does about the frailty of his condemners, even the frailty, in this case, of a man as ordinarily lacking malice as Abraham Lincoln.[28]

Yet Fitz John Porter was also a man very much mistaken about the nature of the war he was fighting. He had imagined that he could make pronouncements on civilian policy (and about a rival general charged with implementing those policies) that no one would notice, that he could ally himself with anti-administration associations without consequences, and that he did not need to concern himself over whether tactical decisions were liable to be understood as political malingering. Although Americans have liked to imagine that the principle of separation-of-powers organizes the civil-military relationship as much as it organizes the branches of government, the truth of that relation is a one-way street. American soldiers may not dally in politics, a lesson taught as early as George Washington’s confrontation with his officers at Newburgh; however, American politicians may—even must—exercise a controlling influence over the military, and the military must submit to that one-way conundrum. Sixty-five years ago, Samuel P. Huntington warned that “the essence of subjective civilian control is the denial of an independent military sphere.”[29] Fitz John Porter, and the American Civil War, may be our most enduring reminders of that reality.

Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Director of the Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship in the James Madison Program at Princeton University.

[1] George Gale to George Washington (September 4, 1792), The Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series, ed. C.S. Patrick (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 11:70; William Marvel, Radical Sacrifice: The Rise and Ruin of Fitz John Porter (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 1-4.

[2] Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General, United States Army (New York: Baker & Taylor, 1908), 1:96; Evalina Porter Doggett, in Otto Eisenschiml, The Celebrated Case of Fitz John Porter: An American Dreyfus (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1950), 309; John J. Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” in Ethan S. Rafuse, ed., Corps Commanders in Blue: Union Major Generals in the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014), 18.

[3] “The Porter Court-Martial,” Washington National Republican (January 10, 1863).

[4] Porter to McClellan (August 1, 1861) in W.C. Prime, ed., McClellan’s Own Story (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1887), 74.

[5] The Mexican War Diary and Correspondence of George B. McClellan, ed. Thomas W. Cutrer (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 63; Donald R. Jermann, Fitz-John Porter, Scapegoat of Second Manassas: The Rise, Fall and Rise of the General Accused of Disobedience (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 124; McClellan’s Own Story, 141.

[6] Porter, in Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 21; Marvel, Radical Sacrifice, 89-90.

[7] Lincoln to McClellan (May 9, 1862), in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. R.P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 5:208.

[8] Heintzelman, in Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 30; Jerry D. Thompson, Civil War to the Bloody End: The Life and Times of Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2006), 195.

[9] Thomas Hyde, Following the Greek Cross: Or, Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1894), 67, 81; Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 33.

[10] John Hay, “Washington Correspondence” (July 27, 1862), in Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the press, 1860-1864, ed. Michael Burlingame (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998), 28

[11] Porter to Joseph C.G. Kennedy (July 17, 1862), in Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 37; Porter to Burnside (August 27, 1862), in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1885), 12(pt 2 – Supplement): 919; Proceedings and Report of the Board of Army Officers, Convened by Special Orders No. 78…in the Case of Fitz-John Porter (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1879), 13; Marvel, Radical Sacrifice, 187, and Burnside (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 106-108.

[12] Pope’s August 27th general order and follow-up order to Porter, his “joint order” to Porter and Irvin McDowell of August 29, and the 4.30 order are in the Official Records, volume 12(pt 2):18, 70-72, 76; see also Pope to Porter and McDowell (August 29, 1862), in Proceedings of a General Court-Martial for the Trial of Major General Fitz John Porter, United States Volunteers, in Executive Documents Printed by order of the House of Representatives During the Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1863), 6-8; “Report of Major General John Pope to the Hon. Committee on the Conduct of the War,” in Supplemental Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1866), 2:154; John S. Slater, An Address to the Soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, and Especially to the Surviving Members of the Fifth Corps, Containing a Brief Review of the Case of Gen. Fitz John Porter (Washington: Thomas McGill, 1880),14; Marvel, Radical Sacrifice, 211; Peter Cozzens, General John Pope: A Life for the Nation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 190; John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 268-9, 306, 464.

[13] Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 306-7, 311-3; Pope to Porter (August 29, 1862), in O.R., 12(pt 2):18, 40, and “Report of Major General John Pope,” 2:155; Cozzens, General John Pope, 155.

[14] Porter, in Proceedings and Report of the Board of Army Officers, 357; James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1896), 188; Scott C. Patchan, Second Manassas: Longstreet’s Attack and the Struggle for Chinn Ridge (Washington: Potomac Books, 2011), 18..

[15] Pope to Halleck (September 1, 1862), in O.R., 12(pt 2): 83; “Report of Major General John Pope,” 2:166-7.

[16] Franklin Sawyer, A Military History of the 8th Regiment Ohio Vol. Inf’y: Its Battles, Marches and Army Movements (Cleveland: Fairbanks & Co., 1881, 65-66); Strong, diary entry for September 13, 1862, in A Diary of the Civil War, ed, Allan Nevins (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 255-6; “Unwritten History of the War: A Talk with a Former Tribune Correspondent,” New-York Tribune (March 14, 1880).

[17] “Special Orders No. 223” (September 5, 1862), in O.R., 19(pt 2):188; Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 41; Eisenschiml, The Celebrated Case of Fitz John Porter, 66.

[18] Ethan S. Rafuse, McClellan’s War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 268; Welles, diary entries for September 7, 1862, and September 2, 1862, in Diary of Gideon Welles, 1:105, 113; Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times, 91

[19] William H. Powell, The Fifth Army Corps (Army of the Potomac): A Record of Operations During the Civil War (New York: G.P. Putnam’s, 1896), 264.

[20] Hennessy, “Conservatism’s Dying Ember: Fitz John Porter and the Union War,” 42; Strother, “Personal Recollections of the War – Tenth Paper,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 36 (February 1868), 282.

[21] “Report of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, U.S. Army, commanding Fifth Army Corps, of the battle of Antietam” (October 1, 1862), in O.R., 19(pt 1):339; Powell, The Fifth Army Corps, 285-6; J.R. Sypher, History of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps: A Complete Record of the Organization (Lancaster: Elias Barr, 1865), 387; John Lord Parker, Henry Wilson’s Regiment: History of the Twenty-second Massachusetts Infantry (Boston: Rand Avery, 1887), 191; Ezra Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, ed. T.G. Clemens (El Dorado, CA: Savas Beatie, 2012), 2:388.

[22] “The Contest in Maryland,” New-York Tribune (September 20, 1862); “Battles in Maryland,” Times of London (October 7, 1862); Eugene D. Schmiel, Citizen-General: Jacob Dolson Cox and the Civil War Era (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2014), 89-90. For variations on Porter’s “thought” about “the only reserves of the army” (which he denied making), see “Battle of Antietam Creek,” New York Times (September 20, 1862), and Thomas M. Anderson, in Jacob Dolson Cox, “The Battle of Antietam,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, eds. R.U. Johnson & C.C. Buel (New York: Century, 1887), 2:656.

[23] Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, 3:1-16; Benjamin Franklin Cooling, Counter-Thrust: From the Peninsula to the Antietam (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 256.

[24] Marvel, Radical Sacrifice, 263, 267; History of the Corn Exchange Regiment, 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers (Philadelphia: John L. Smith, 1888), 107-8; Powell, The Fifth Army Corps, 322; Evan Morrison Woodward, Our Campaigns: Or, The Marches, Bivouacs, Battles, Incidents of Camp Life (Philadelphia: John L. Potter, 1865), 224-5.; “Arrival of Gen. Hooker,” New York Times (November 15, 1862); “The Courts of Inquiry,” Washington Evening Star (November 25, 1862); “The Case of Gen. Porter. A Court Martial Ordered,” New-York Tribune (November 26, 1862).

[25] Proceedings of a General Court-Martial for the Trial of Major General Fitz John Porter, 2-9, 69, 313; “The Porter Court-Martial,” Washington National Intelligencer (January 3, 1863); “The Porter Court-Martial,” New-York Tribune (January 12, 1863); “The Verdict Rendered,” New York Times (January 12, 1863); Lincoln, “Order Approving Sentence of Fitz John Porter” (January 21, 1863), in CW, 6:67; Orville Hickman Browning, William D. Kelley & Robert Todd Lincoln, in Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, eds. Don & Virginia Fehrenbacher (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 66, 276, 298; Swett, in Robert S. Eckley, Lincoln’s Forgotten friend, Leonard Swett (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), 125. Whether Lincoln actually had time to read the entire 900-page report, or even glance through parts of it, remains a matter of dispute.

[26] Johnson, A Reply to the Review of Judge Advocate General Holt, of the Proceedings, Findings and Sentence of the General Court Martial in the Case of Major General Fitz John Porter (Baltimore: John Murphy, 1863), 4; William C. Harris, Two Against Lincoln: Reverdy Johnson and Horatio Seymour, Champions of the Loyal Opposition (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), 53-54; Upton to James Garfield (December 8, 1879), in Peter Smith Michie, The Life and Letters of Emory Upton (New York: D. Appleton, 1885), 460.

[27] “The Taint of Treason,” Vermont Watchman & State Journal (March 24, 1880); Cox, The Second Battle of Bull Run, as Connected with the Fitz-John Porter Case (Cincinnati: Peter J. Thompson), 71; Marvel, “The Framing of Fitz John Porter,” Civil War Monitor 12 (Summer 2022), 65. Even to the present, some chroniclers of the battle lay “the real cause of the lost battle” at “Porter’s inaction, and the real cause of his inaction was almost certainly a tacit understanding among the Democrats of the Army of the Potomac not to allow Pope a victory that would make him overshadow the Democrats’ idol, McClellan.” Wallace J. Schutz and Walter N. Trenerry , Abandoned by Lincoln: A Military Biography of General John Pope (Urbana: University of Illinois press, 1990), 168.

[28] Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 465.

[29] Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil–Military Relations (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 83.