We Mourn Our Fallen Father: Abraham Lincoln’s Easter Sermon and the Beginning of his Martyrdom

We Mourn Our Fallen Father: Abraham Lincoln’s Easter Sermon and the Beginning of his Martyrdom

By Kayla Gustafson

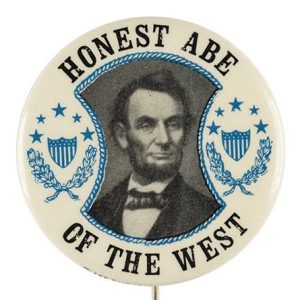

During his life, Abraham Lincoln bore a myriad of nicknames: the Railsplitter, Honest Abe, Father Abraham, and the Liberator, just to name a few. But, after his death, he became a martyr for the nation, that martyrdom being proclaimed in sermons on Easter Sunday in 1865.

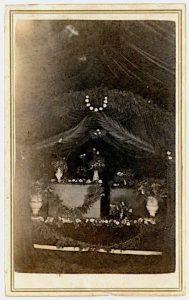

The timing of the assassination made Easter Sunday 1865 highly important to citizens from all walks of life. Easter 1865 was supposed to be a joyous occasion, a mix of rejoicing the risen Christ and the end of the Civil War, but, instead, it was a day of mourning and great loss. Abraham Lincoln was shot on Good Friday and died on Holy Saturday. As the news of his assassination spread throughout the country, parish women removed the daffodils and brightly-colored tulips from their parishes, leaving the white Easter lilies. They brought in black fabric and draped it along the altar, windows, and pulpit. They added paintings and photos of the fallen President and draped those, too, in mourning. This day would be remembered in history as “Black Easter.” Rev. James Smith Bush of Grace Church in Orange, NJ, explained, “We do not give up our Easter flowers to-day, but wreath them even around the garments of our mourning.”

Church leaders from all faiths, faced with the shock of the news and the grief of the nation, changed their sermons overnight making them into funeral sermons. Abraham Lincoln guided the nation through one of its darkest times, from being the Commander-in-Chief throughout the Civil War to being the “Great Emancipator.” He paid the ultimate price for the American people. Some religious leaders would say that Lincoln died for the sins of the republic.

The image of Lincoln painted by religious leaders in these sermons can still be seen today. The characterizations can be categorized into four tropes: the Great Emancipator, a man who is larger than life, the common self-made man, and the Champion of Democracy.

Rev. Charles H. Hall of The Church of the Epiphany in Washington, D.C., wrote his sermon, “A Mournful Easter: A Discourse,” in haste the Saturday night before delivering it. Rev. Hall was chosen to be one of four ministers to lead services at the White House funeral the following Wednesday. The following excerpt is a touching sentiment:

“We gather now around an open grave, permitted to be opened on this Easter Day by the awful and wicked tragedy of this last Good Friday, to temper our pious gratulations as believers with the sorrow which has befallen us as citizens. The grave and gate of death open before us as a people, and we mourn the sanguinary crimes which have made our Good Friday so marked an event in the history of the world… We are an afflicted nation, horrified by the darkest crimes which can befall a people.”

Hall closed his discourse with the appeal:

“May God give comfort to the afflicted families, whose losses will make Good Friday memorable in our national records. May He give repentance to the wretched criminals who have stained their hands, wantonly and stupidly in innocent blood, before they are called upon to meet the just punishment for their atrocities. May He give us grace to understand the seriousness and solemnity of our duties to the government over us; and as He only can, bring good out of this evil.”

In many sermons, Lincoln took on a larger-than-life form—that of a messiah, a man deemed the bringer of liberation. This notion hearkens back to Lincoln’s visit to Richmond. Admiral David D. Porter, who landed with Lincoln in Richmond on April 4, 1865, recalled,

“There was a small house on this landing, and behind it were some twelve negroes digging with spades. The leader of them was an old man sixty years of age. He raised himself to an upright position as we landed, and put his hands up to his eyes. Then he dropped his spade and sprang forward. ‘Bress de Lord,’ he said. ‘Dere is de great Messiah! I knowed him as soon as I seed him. He’s bin in my hear fo’ long yeahs, an’ he’s cum at las’ to free his chillun from deir bondage! Glory, Hallelujah!’ And he fell upon his knees before the President and kissed his feet. The others followed his example, and in a minute, Mr. Lincoln was surrounded by these people, who had treasured up the recollection of him caught from a photograph, and had looked up to him for four years as the one who was to lead them out of captivity. “

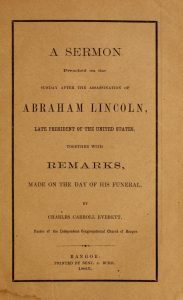

In his sermon, Rev. Charles Carroll Everett of the Independent Congregational Church of Bangor, ME, reminisced on the President’s visit to Richmond: “We remember now, what we read with a smile before, how the poor freed negroes of Richmond greeted him by the name of “Jesus,” him their savior and their deliverer. To them he did represent, so far as any outward form could do it, the power of Christ, to break the chain and set the captive free.”

In their last-minute writing, many religious leaders searched for possible parallels between biblical figures and Lincoln; the characterization was one that religious leaders understood well and could lean on in their sermons. Rev. Alexander S. Twombly of the State St. Pres. Church in Albany, NY, said in comparison that, much like Moses, Lincoln didn’t live to see the “promised land.” Lincoln led the nation through one of the darkest chapters of American history, watching countless men die for the sake of a free nation. Lincoln, much like Moses, died just as he came to see the free land. He also parallels Moses in his goal of freeing enslaved men and women. Rev. John Falkner Blake of Christ Church in Bridgeport, CT, also saw similarities between Abraham Lincoln and the biblical figure Moses. Blake stated: “I know the depth of your love for our murdered President, and therefore I ask you to weep with me to-day while we consider his late relations to us as a people. As I ponder over them, they seem to me to bear a striking analogy to those which Moses sustained to the children of Israel.” The Reverend continued: “…We had all become slaves, and as God sent Moses to deliver the children of Israel from slavery, so, I believe, he sent Abraham Lincoln to deliver us.”

Rev. Samuel Gorman of the First Baptist Church in Canton, OH, had a similar statement: “He will be remembered by his friends, as the Benefactor of our Republic and of our race. And how precious will be his memory to the millions whom he has helped to free! He will be to them as Moses has ever been to the Jews. This generation will tell of his greatness and goodness to the next, and so on, down to the end of time.”

Rev. Charles S. Robinson of the First Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, NY, made special note in his sermon to remember the “poor freedmen”: “I think more than all, of the poor freedmen, when they hear of the President’s death. How they will wonder and will wail! They called him “Father,” as if it were part of his name. Oh, they believed in Abraham Lincoln! They expected him, as the Israelites did Moses.”

Other leaders found refuge in the parallels between Jesus Christ and Lincoln. One such leader was Rev. Cephas Bennett Crane of The South Baptist Church in Hartford, CT. He exclaimed:

“Yes, it was meet that the martyrdom should occur on Good Friday. It is no blasphemy against the Son of God and the Savior of men that we declare the fitness of the slaying of the Second Father of our Republic on the anniversary of the day on which he was slain. Jesus Christ died for the world; Abraham Lincoln died for his country. The consecration of Jesus to humanity began in the antiquity of eternity, and found its culmination when he cried with white, yet triumphant, lips, on the cross, “it is finished.” The consecration of Abraham Lincoln to the American people had its phenomenal and most manifest beginning in the summer of 1858 when he entered upon that memorable Senatorial Campaign…”

Religious sermons were written with one of two distinct, yet contradicting, images of Lincoln. He was either a man who represented frontiersmen, the working class, and common and average Americans, or he was superhuman, larger than life, and closer to biblical figures and royalty. Lincoln, a man who rose above his station, liberated slaves, took a broken nation and pieced it back together, did in fact come from impecunious beginnings.

During the 1860 election, Lincoln was nicknamed the Railsplitter at the Republican Convention, solidifying his image of being a common man. He gave the average citizen a voice in the political chasm of 1860. Lincoln’s opponents were more well-known and elite politicians. By the 1864 election, Lincoln was called Father Abraham, the father of the nation, the man who freed the slaves. There began his shift from a common to an extraordinary man. Clergymen cemented these characterizations in the sermons they preached the day after Lincoln’s death.

Rev. Theodore L. Cuyler of the Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, NY, preached, on the following Wednesday, of Lincoln being an ambitious common man, one of humble beginnings who made himself into an honest and noble statesman—a feat so inherently American. Cuyler gave a short biography of Lincoln’s life, focusing on the careers that he pursued:

“Born in Hardin County, Kentucky, of farmer parentage, on the 12th of February, 1809; his boyhood spent in clearing forests with the woodman’s axe; one year only spent in the rudimentary studies of a district school; at the age of nineteen toiling as a hired hand on a Mississippi flat-boat; then a clerk in a country store of Illinois; next a student of law from a few books borrowed in the evening, to be returned in the morning; in 1834 a member of the State Legislature; in 1846 in the National congress… and from that lofty eminence, in the very moment of victory, translated through martyrdom to a seat in history beside our first Washington himself.”

On the other hand, Rev. John H. Drumm of St. James Church in Bristol, PA, focused on Lincoln as an extraordinary man, stating that “he was more than a great man: he was our PRINCE… by our own free and deliberate choice!” Giving Lincoln the title of “prince” painted him as American royalty. The position of a royal is one a common person could never imagine inheriting, but Drumm stated that Lincoln ascended to royalty much like the first US president, George Washington.

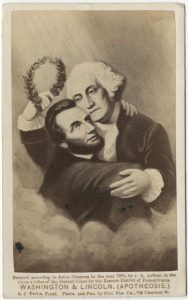

After his death, Lincoln’s image started to take the form of an American myth. His character became tied to those of the founding fathers, the leaders of this land who fought for liberty against all odds. Many clergymen took the stance that Lincoln’s character is rivaled only by that of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Rev. Everett portrayed the verbal picture of Lincoln’s soul entering heaven, stating “Already the pure, the incorruptible humble souls of all times, have welcomed him; already has Washington greeted him as brother; and Christ welcomed him…” Rev. Drumm preached something similar to Everett, saying, “[Lincoln is] so noble, so spotless is it, that I hesitate not to say that, next to George Washington, his will be the purest and noblest record in the annals of this land.” Rev. M.P. Gaddis of Sixth Street M.P. Church in Cincinnati, OH, chose for his sermon the subtitle Washington the Father, Lincoln the Savior of Our Country.

As the nation mourned the fallen president, religious leaders tried to calm the crowds of people who attended religious services on that Easter. Easter is a high holy day where believers make it a point to observe their faith. On Easter of 1865, the crowds grew to twice their normal size with people rushing to services in hopes of finding peace. Lincoln was the first president to be assassinated, shocking the nation. Never before had the nation been faced with such a horrendous crime. How would they overcome this grief? Many turned to their faith, attending church on Easter, hoping this could help them find the peace that they needed.

After hearing these sermons, congregants found a great deal of respect for the fallen president. The man who worked unceasingly to bring the broken country back together, to free the enslaved, and to bring the country peace would never get to experience the new-found freedom he helped create. This solidified his legacy as an American martyr.

Kayla Gustafson is a Senior Lincoln Librarian at the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, IN. The sermons cited are curated in the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection at the library.