The Grant Administration & International Law

“Respect the Rights of All Nations, Demanding Equal Respect for Our Own”[1]

“Respect the Rights of All Nations, Demanding Equal Respect for Our Own”[1]

The Grant Administration & International Law

Burrus Carnahan

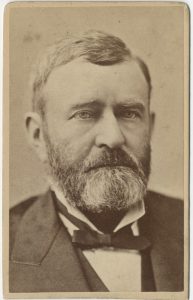

In the last decade, historians have reassessed the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Previously considered one of our worst presidents, new scholarship has discovered accomplishments and strengths earlier ignored. Grant wanted “let us have peace” to be the dominant theme of his administration. It is therefore surprising that Grant’s contribution to the development of international law has been relatively neglected in recent reassessments. The Grant administration established important precedents in the peaceful settlement of disputes, in the law of war and neutrality, and in the protection of human rights in both war and peace.

The CSS Alabama Arbitrations

One success of the Grant administration has received considerable attention, more from scholars of international law rather than from Presidential historians. This was the 1872 judgment of an international tribunal awarding the United States $15,500,000 against Great Britain for the so-called “Alabama claims.”

At the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy sent naval officer James Bulloch to the United Kingdom to build or purchase warships there. The British government had declared itself neutral in the war, so Bulloch had to act clandestinely because the Foreign Enlistment Act prohibited British subjects from arming or “fitting out” naval vessels for use against a belligerent power at peace with Great Britain. Through Bulloch’s skill at deception, together with bureaucratic bungling, ambiguity in the law, and perhaps, as many Americans suspected, unofficial English sympathy for the South, several Confederate warships sailed from British ports to prey on Union maritime commerce.

The most notorious of these was the CSS Alabama, constructed in England at Bulloch’s direction and sailing from Liverpool on July 29, 1862. Between then and her destruction by the USS Kearsarge on June 19, 1864, Alabama captured over 60 Northern merchant vessels. She still holds the record for the most tonnage of enemy merchant shipping destroyed in war, a record not exceeded by any submarine or commerce raider in either World War. The Alabama and Bulloch’s other ships obliterated pre-war Yankee dominance in the international carrying trade.

Britain initially refused to admit that the US damage claims had any legitimacy at all, but she finally expressed “regret” at American losses. (Expressing regret is a diplomatic dodge still used by governments to make sympathetic noises about damage done to another state’s interests without conceding that they had actually done anything wrong.)

President Grant nevertheless insisted

that the Alabama claims be decided by arbitration. In the 1871 Treaty of Washington, the United Kingdom agreed to submit the American claims to a five-member international tribunal to meet in Geneva, Switzerland. The United States and Britain would each name one judge, with the other members chosen by Italy, Brazil, and Switzerland.

While continuing to refuse to admit that she had violated any rules of neutrality as they existed in the 1860s, Britain agreed in Article VI of the Treaty that the tribunal should apply the following three rules in judging its behavior during the Civil War:

“First, to use due diligence to prevent the fitting out, arming, or equipping, within its jurisdiction, of any vessel which it has reasonable ground to believe is intended to cruise or to carry on war against a Power with which it is at peace; and also to use like diligence to prevent the departure from its jurisdiction of any vessel intended to cruise or carry on war as above, such vessel having been specially adapted, in whole or in part, within such jurisdiction, to war-like use.”

“Secondly, not to permit or suffer either belligerent to make use of its ports or waters as the base of naval operations against the other, or for the purpose of the renewal or augmentation of military supplies or arms, or the recruitment of men.”

“Thirdly, to exercise due diligence in its own ports and waters, and, as to all persons within its jurisdiction, to prevent any violation of the foregoing obligations and duties.”

Finally, both parties agreed that these rules would apply to future wars in which they were involved, and to ask other nations to agree to them as well. In 1907, at an international conference at the Hague, Netherlands, these rules were included in a multilateral treaty called the Convention on International Neutrality in Naval War and are now widely considered to be part of international law.

At the Geneva tribunal, the United States claimed that the United Kingdom had violated the three rules in its handling of 14 ships used by the Confederacy. In the end, the tribunal found, by four votes to one (Britain dissenting) that it had failed to exercise due diligence in the cases of the Alabama and two other vessels, the Florida and the Shenandoah. Like the Alabama, the Florida had been built at Liverpool with secret Confederate financing and allowed to escape British territory despite US diplomatic protests. Between January, 1862, and September, 1864, she captured 37 US merchant ships.

The Shenandoah, on the other hand, had been built in Scotland as a legitimate merchant vessel named the Sea King. In 1864 she had completed one commercial voyage before being secretly purchased by the Confederacy and sailed to Spanish territory to be armed and commissioned as the CSS Shenandoah. The tribunal did not find Great Britain at fault for allowing her to leave Britain. In early 1865, however, the Shenandoah had called at the British colony of Australia, having already captured twelve American merchant ships. Great Britain was found to have failed to exercise due diligence to prevent her from being repaired, resupplied, and recruiting crewmen in Australia, over the protests of the US consul at Melbourne, and the British government was held liable for the loss of the 26 ships she captured after leaving that port.

The Alabama arbitration is still regarded as a major precedent for the peaceful settlement of international disputes. In the words of the Australian legal scholar Julius Stone, “The importance of this case in the history of arbitration is independent of the particular outcome. For it showed that arbitration could be used for claims … involving interests which important Powers regarded as major and even vital ….” The success of the Geneva tribunal soon led to numerous other arbitrations involving nations in both Europe and the Western Hemisphere.

British Claims Against the United States

In addition to the Geneva tribunal, the Treaty of Washington also created a three-member arbitral commission to consider other claims arising from the Civil War, chiefly those of British subjects who owned property, located in rebel territory, that had been seized or destroyed by the Union army. President Grant named James Frazer, a former justice of the Indiana Supreme Court, as the US member and Russell Gurney, a member of Parliament, represented Great Britain. These two selected Count Louis Corti, the Italian ambassador to the United States, as the third member. This tribunal sat in Washington, DC, from 1871 to 1873, and heard 478 claims against the United States. Only 181 of these were found justified, and an award of $1,929,818 was made against the United States.

Before 1800, it was generally accepted that all enemy property, whether owned by the government or private citizens, was subject to confiscation or destruction in war. By the 1860s, however, a consensus had developed among legal experts that private property of enemy citizens should be protected unless there was a “military necessity” for its seizure or destruction, that is, unless there was a valid military reason for it.

During the war, President Lincoln had invoked this principle as a legal justification for the Emancipation Proclamation in his August, 26, 1863, James Conkling Letter. If, as the Confederacy claimed, slaves were property, then, he reasoned, “Is there–has there ever been–any question that by the law of war, property, both of enemies and friends, may be taken when needed? And is it not needed whenever taking it, helps us, or hurts the enemy?”

The decisions of the Washington tribunal established early precedents for the application of military necessity to the treatment of civilian, in this case neutral, property. The commission thus disallowed claims for British property damaged by bombardment during sieges of cities, or destroyed to clear a field of fire for artillery. Also disallowed was a claim for destruction of a sawmill in Mississippi by a Union raiding party, when the mill had produced wooded ties for southern railroads. Similarly disallowed was claim for the destruction of a foundry and machine shop in Atlanta, before General Sherman’s army abandoned that city for his march to the sea.

The precedents with the most far-reaching significance related to the destruction of British-owned cotton. The United States argued that cotton played a unique role in the Confederacy’s war economy. As restated in the American counsel’s report to the Secretary of State, cotton was “the great staple from which … derived the principal means of that government for the carrying on of the war, which was the principal basis of its credit, the source of its military and naval supplies, and on which it relied to maintain its independent existence ….” All but one of the numerous claims for destroyed cotton were denied. (The exception involved a claimant who had been granted a license by the US Treasury to deal in Confederate-controlled cotton. Frazer dissented, arguing that the license had been procured by fraud.)

The decision that it was lawful to attack industries supporting an enemy economy would assume major significance with the invention of the airplane in the 20th century. It was used to justify strategic

bombing in both World Wars. Most recently, the successful American air campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria concentrated on oil and banking facilities supporting the enemy.

Surprisingly, the Washington tribunal denied most claims for pillaging by Union troops. In its defense, the United State relied on European precedents, principally the denial by the Austrian Empire of British claims based on looting by the Austrian army when suppressing an 1848 revolt in northern Italy. The argument was that a certain amount of looting was to be expected during any large-scale military operation, and was just a normal incident of warfare.

While this assumption has been rejected by later developments in the law of war, the one pillaging claim that was allowed has significance for other reasons. In Missouri, members of the 7th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, US Army, had pillaged a country store owned by a British national. The 7th Kansas was more commonly known as “Jennison’s Jayhawkers.” Hatred between the citizens of Kansas and Missouri went back to the “Bleeding Kansas” era of the 1850s, when gangs of Kansans and Missourians fought over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. “Jayhawkers” was a common nickname for the anti-slavery Kansans. Both sides terrorized the other’s civilians, a practice revived during the Civil War.

The colonel of the 7th Kansas was Charles R. Jennison. Historian Thomas Goodrich has described him as “a genuine savage.” During the winter of 1861-62, according to Goodrich, Jayhawker bands “went on a rampage of theft, arson and murder” in Missouri. “None displayed more ferocity nor reached greater heights of savagery than Jennison’s regiment.”[2] The US counsel’s 1873 report to the Secretary of State conceded that the evidence showed “great neglect of discipline on the part of Colonel Jennison, … and his neglect and refusal to take any steps for the surrender of the stolen property or the punishment of the offenders ….”

On these facts, the tribunal unanimously approved an award of damages. This decision established a precedent for the modern principle that governments have a duty to maintain discipline in their armed forces, to include enforcing the laws of war. Grant vocally supported peaceful settlement of international disputes for the rest of his life. In 1877, during his post-presidential world tour, he spoke to a pro-arbitration group in Birmingham, England. There he expressed the hope that, “at some future day the nations of the earth will agree upon some sort of congress,” that would render binding decisions on international “questions of difficulty,” thus anticipating the 20th century League of Nations and United Nations. While neither of these organizations lived up to the hopes of its founders, Grant’s speech demonstrated thinking far ahead of his time.[3]

The Humanitarian Role of Neutral Powers

Elihu Washburne was a congressman from Galena, Illinois, Ulysses Grant’s home town at the start of the Civil War. A strongly anti-slavery Republican, he was an ally of the Lincoln administration and Grant’s legislative sponsor during the Civil War, supporting his promotions and defending him from political critics.

When Grant became president in 1869 he appointed his friend to the plum diplomatic post of American minister Paris. Neither realized, of course, that in 1870 the French Emperor Napoleon III would plunge his country into war with Prussia and its German allies in the North German Confederation.

When armed conflict breaks out between nations, each country normally breaks off diplomatic relations with the other. In such circumstances it is common for a country to request a neutral nation, known as the “protecting power,” to act as a channel for diplomatic communications with the enemy and to otherwise look out for its interests.

In 1870 the United States accepted this role on behalf of France’s German enemies. As President Grant reported in his State of the Union message for that year, soon after war broke out, “the protection of the United States minister in Paris was invoked in favor of North Germans domiciled in French territory. Instructions were issued to grant the protection.” Protection was later extended to Prussian allies Saxony, Gotha, Hesse and Sax-Coburg. The President noted that the “charge was an onerous one, requiring constant and severe labor, as well as the exercise of patience, prudence and good judgement.”

The task was onerous because Washburne had gone beyond the minimum diplomatic tasks of his position to extend humanitarian assistance to the thousands of Germans, most of modest economic means, residing in France. As enemy aliens they were subject to expulsion or internment by Napoleon’s government. The US mission issued safe-conduct passes and arranged railroad transportation for 30,000 Germans expelled from France. For those who remained, Washburne’s mission intervened on behalf of those arrested for espionage on inadequate evidence, distributed relief funds from their home governments, and provided other assistance. President Grant expressed his “entire satisfaction” with Washburne’s performance, an opinion later echoed by the French and German governments.

With President Grant’s support, the American diplomatic initiative during the Franco-Prussian War laid the foundation for an expansion, during the later 19th and 20th centuries, of protection by neutral powers of enemy civilians, prisoners of war, and other war victims. The humanitarian role of protecting powers is now codified in the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

Human Rights Protection of Religious Minorities

The single most disturbing incident in Grant’s career occurred on December 17, 1862, when, as major general commanding the Military Department of the Tennessee, he issued an order expelling all Jews, “as a class,” from the area under his command. The order was quickly rescinded at the direction of President Lincoln, and thereafter Grant was embarrassed at having issued it. As he explained to a friend on September 29, 1868, the order had been hurriedly issued ‘without one moment’s reflection” at a time when he believed Jewish merchants were engaged in smuggling goods to the Confederacy. He specifically repudiated the order, rejected “prejudice against any race or sect,” and wanted “each individual to be judged by his own merit.”

During his presidency, Grant tried to make up for the order, personally attending the opening of a new synagogue in Washington, DC, and appointing a record number of Jewish officials. At the international level, he asked the State Department to protest the forcible movement of 2000 Jewish families by Russia. Czar Alexander II eventually reversed the removal order, though it is not clear to what extent this was due to foreign reaction.

In response to newspaper reports of pogroms in Romania, then a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, Grant visited the State Department to request investigation of the reports and ask the Turkish government to intervene on behalf of the Jews. In further response to the situation in Romania, in 1870 Grant appointed an American Jew, Benjamin Franklin Peixotto, as US consul in Bucharest. The President analogized his role to that of “a missionary … for the benefit of the people who are laboring under severe oppression …,” i.e., the Jews. During his five years as consul, Peixotto formed a friendship with the country’s ruler, Prince Carlos I, formerly Prince von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen of Germany. While the prince was constrained by his country’s 1866 constitution (which denied civil rights to Moslems and Jews), Carlos retained considerable influence as a national symbol and, at the urging of Peixotto, was able to prevent some pogroms and moderate anti-Semitic policies of elected politicians. After an 1872 riot involving alleged Jewish desecration of a church, the US consul sheltered some victims in his home and was able to secure the release of those wrongly charged.

Grant’s support for international human rights was far ahead of its time, and was opposed by his own Secretary of State. Under 19th century international law, persecution of ethnic and religious minorities was regarded purely an internal matter, off-limits to official expressions of concern by other governments. The President nevertheless persisted. As his biographer Ron Chernow observed, “Grant set a new benchmark for fostering human rights abroad.”

Conclusion: “It is too late in the day to persecute any one on account of condition, birth, creed, or color”[4]

By submitting the Alabama claims to an international tribunal, President Grant was arguably pursuing not only the peaceful settlement of an important dispute, but also the interests of the United States. In light of British reluctance to even entertain the claims, a negotiated settlement was unlikely. That is less true of the war claims considered by the Washington tribunal. Little publicity was given to its activity, probably deliberately. The American public was isolationist, and was unlikely to welcome foreigners judging the legitimacy of military measures taken to save the Union.

Napoleon III had tried to violate the Monroe Doctrine and had leaned towards the Confederacy, so US public opinion was hostile to France at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War, a sentiment shared by President Grant. Still, American exertions as protecting power for German nationals went contrary to the general isolationism of the American public and served no material interest of the United States. Fundamentally, Grant’s decision to back his Minister in Paris rested on humanitarianism. Again, as his own State Department pointed out, no discernable US national interest justified Grant’s policy of promoting the human rights of foreign Jews.

A soldier who had fought in two major wars, as an infantry subaltern and as a commanding general, Grant knew the inherent cruelty of war. As president he left his country a worthy legacy of promoting peace and humanity in international relations.

Burrus M. Carnahan is Adjunct Professor of Law at George Washington University.

[1] First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1869 in Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 19: July 1, 1868-October 32, 1869, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois U. Press, 1995) 139, 142.

[2] Thomas Goodrich, Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border (Bloomington: Indiana U. Press, 1995) 24

[3] Speech to the Midland International Arbitration Union, October 16, 1877, in Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 28: November 1,1876-September 30, 1878, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois U. Press, 2005) 290-291.

[4] President Grant’s reaction on hearing of Russian persecutions, quoted in Washington Chronicle December 1, 1869, in Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 21: November 1,1870-May 31, 1871, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois U. Press, 1998) 76.