Interview with Jay Winik

Interview with Jay Winik by Sara Gabbard

Sara Gabbard: Your book April 1865: The Month that Saved America is a “must read” for those intent on understanding the ramifications of the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, and the aftermath of both assassination and war. What prompted you to undertake this challenge?

Jay Winik: When I was searching around for a topic for my book, I was trying to find something that I thought would be fresh, would be exciting, would have a pounding narrative, and would really change the way people look at things. What really struck me about April 1865 is that you had this dramatic surrender at Appomattox, this moving surrender at Appomattox, yet it was not a surrender of the entirety of the Confederate Army, and then five days later, Abraham Lincoln was dead. I thought that’s the story that we don’t hear enough about, and that’s the story that needs to be told. That in the end is what prompted me to undertake the lofty challenge of making sense of what would become April 1865. One thing I would add is that the readers obviously agreed with me.

SG: Tell our readers something about Lincoln’s meeting at City Point with Grant and Sherman as April 1865 dawned.

JW: As April 1865 was about to dawn, Abraham Lincoln called the very important meeting with his two top generals, Ulysses S. William and William T. Sherman. He wanted to talk about the war: when it would end and how it would end. He did some things that were really quite crucial there. One of the first things he said to them was something that had deeply concerned him. That was the possibility, as Lincoln put it, that the southerners would take to the hills with their hearty horses and hearty men and then wage in effect what would be guerrilla warfare. At that point Grant agreed that was a real possibility. And then Lincoln wanted to talk about something else with both Grant and Sherman and that was, as he put it, that there would be one final bloody Armageddon. And he said, “Must there be more bloodshed, must there be one final great battle?” Grant said, “Lee being Lee, there will be a final cataclysmic war.” There was one other thing that Lincoln wanted to talk about. It was an extremely insightful comment: when this war is over, there must be no bloody work, no hangings, there must be none of that. In other words, what he was talking was the need for a soft peace. His reference was to something that loomed large in the minds of all Americans in that day and age: that there could be a repeat of the French Revolution in America with terrible consequences of an ongoing cycle of bloodshed and civil war that would continue on without end.

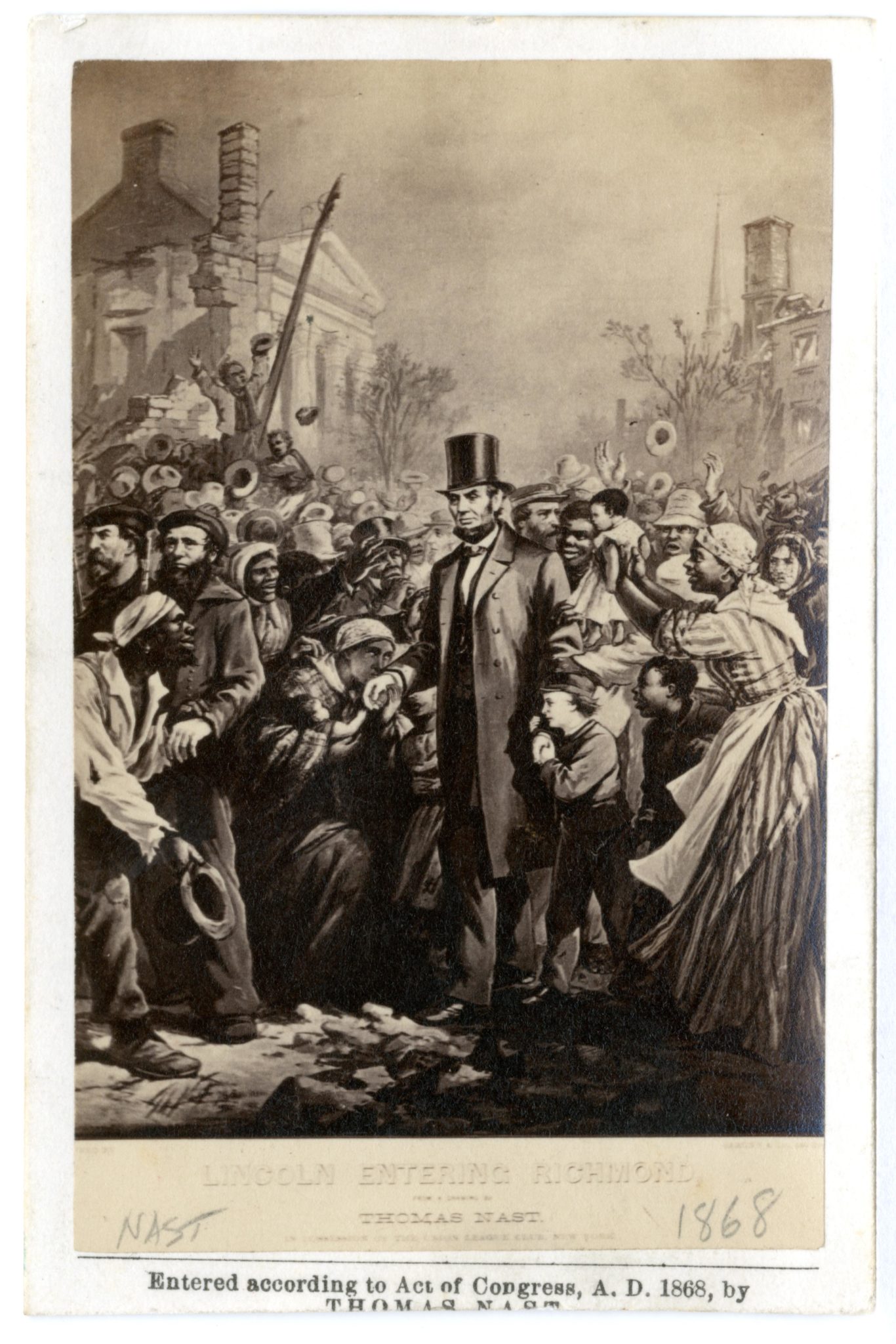

SG: Can you please describe Lincoln’s appearance in Richmond on that stirring day of April 4th?

JW: As Lee was retreating, this had to have been one of the most stirring days, not only in the entirety of April, not only in the entirety of the Civil War, but in the entirety of all American history if not modern contemporary history. Lincoln wanted to see the now-fallen rebel capital, and he wanted to see it with his own eyes. He got into a small boat and made his way to Rocketts Landing in Richmond. He then got off the boat and was surrounded by a number of men who were there to guarantee his security. All of a sudden President Lincoln saw a crowd of African Americans, many of whom had been slaves. They wanted to get a look at the man they considered to be their liberator. They wanted to see him with their own eyes. They tried to touch him. At one point, Lincoln said to them very poignantly, “You’re free, you’re free as air.” It was at that point another one of these former slaves threw himself at Lincoln’s feet, and the president wagged a stern finger at him and said, “From now on you do not kneel to me, you kneel to your God, you kneel only to your creator.” He then proceeded to visit the office of Jefferson Davis. That was that stirring day in Richmond that will live in time and memorial as a powerful moment in American history.

SG: Could you please comment about Lee’s retreat and its significance?

JW: If you think about what Abraham Lincoln was saying to Grant and Sherman, he was talking about a “soft peace” and reconciliation. Lincoln had his ideas, but Robert E. Lee had a totally different mindset. Lee was thinking that he could retreat from Richmond as well as Petersburg, take his army down south, hook up with Joe Johnston, and from there he would strike at William Sherman. He would then “take to the hills” and continue the war from there, prepared to fight as long as possible. Lincoln feared more than anything else this mindset of Lee. In the actual retreat itself, all Lee had to do was “hook down south” with his army and link up at a place called Amelia Courthouse, where rations were waiting for him. When Lee began his retreat, this epic military measure spawned over four sets of long lines stretching over thirty-five miles each. However, when he left Richmond and Petersburg, he had taken military equipment but no food. His men marched hour after hour and day after day, and finally arrived at Amelia Courthouse. Lee made his way to the train tracks, where the precious cargo was waiting for him. He opened up one of the boxcars, and what did he find? He found weapons and other military equipment. He found everything but food and water. In other words, the absence of these essentials threatened to undo this mighty Army of Northern Virginia. But it was at this point that Lee resolved that he and his men would fight with whatever they had. They would continue this retreat with great spirit and determination. On April 7th they would have a bitter battle against the North at a place called Saylor’s Creek. They would fight with their weapons, but they would be fighting hand-to-hand combat as well. Lee’s forces eventually lost this battle, and by April 8th and then April 9th, it was obvious that they were surrounded on the east, west, and south sides. The option to head north was not a viable alternative. It was at this point that Lee was forced to consider surrendering.

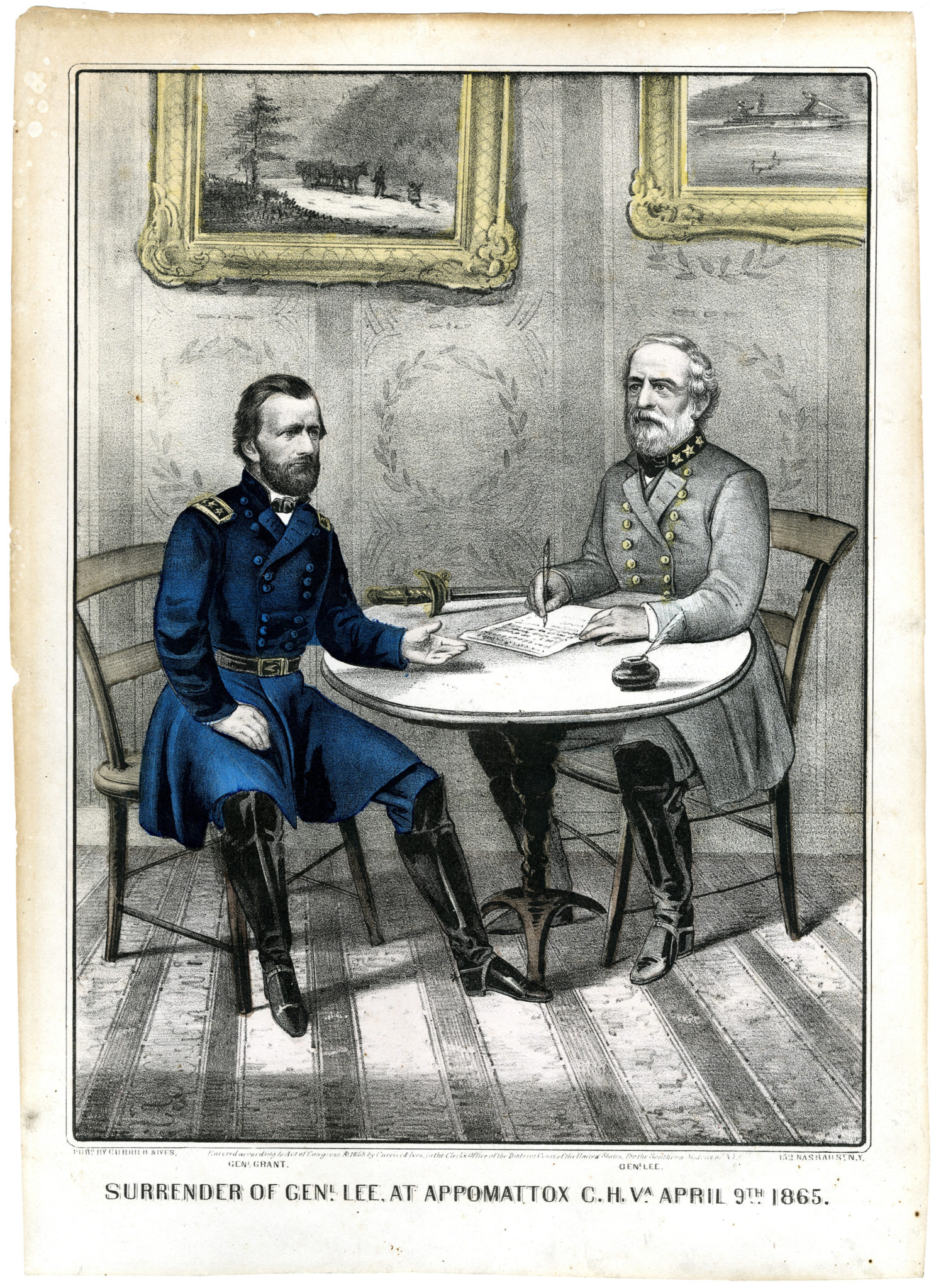

SG: Please describe what you consider to be the most generous terms of the peace treaty at Appomattox.

JW: This is one of the great moments in all of American history. Grant and Lee met at the Wilmer McLean house. Lee wore his finest uniform, and Grant appeared in muddy military clothes. The most important provisions were: Confederate soldiers were allowed to return to their homes, and they were allowed to keep their horses. After the signing of the treaty, Lee left the house, mounted his horse Traveler, and left the premises.

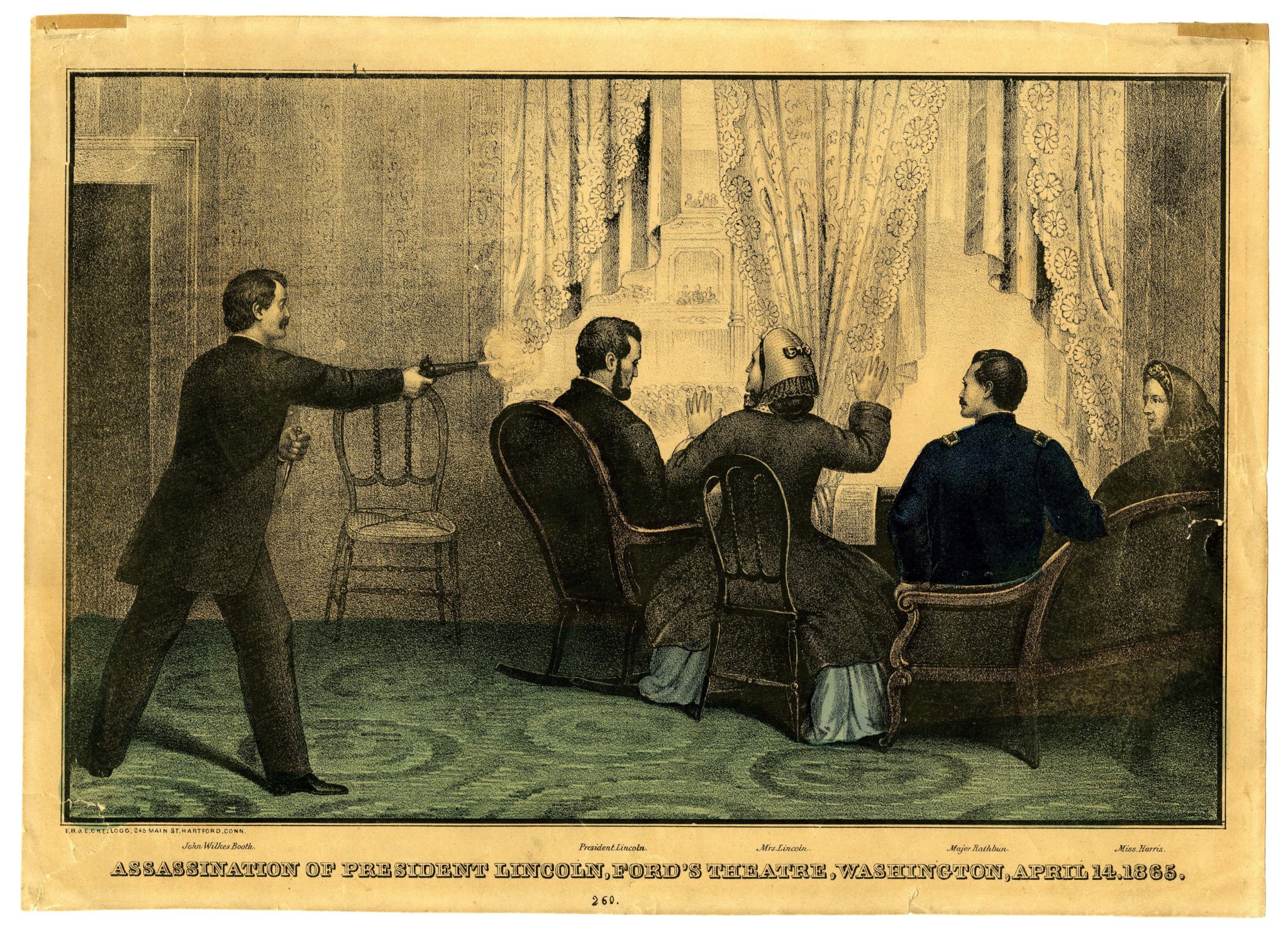

SG: Since your book is titled April 1865 would you please comment on the assassination in that month?

JW: What’s so dramatic is that when Lee surrendered, he surrendered only his army. There were still three Confederate armies in the field, ready to fight to the bitter end. Also, there was still Mary Lee, who was a direct descendant of Martha Washington, calling for continued fighting; and there was Jefferson Davis calling for guerrilla warfare. The situation was so unstable that chances for reconciliation were, at best, uncertain. Five days later in Washington, D.C., on April 14th, three deadly assassins fanned out across the city. First was, of course, John Wilkes Booth, who shot the president at approximately 10:15 p.m. The next morning at 7:22 a.m., the great Abraham Lincoln died. The second deadly assassin made his way to Secretary of State William Seward’s house, managed to gain access to his bedroom, and stabbed him multiple times. Seward’s life was left hanging by a thread, but he survived. The third member of the assassination conspiracy planned to kill the vice president, Andrew Johnson, but by happenstance, he got cold feet at the end and did not make an assassination attempt. Imagine the chaos and the turmoil that rippled through Washington, D.C., at that point. That was the 9/11 of their day. Indeed, the Chief Justice of the United States said it was a night of horrors. It was a night of chaos. The American people had not had sufficient time to experience the relief promised after the surrender of Robert E. Lee when their president was taken from them.

SG: How real was the threat of guerilla warfare by Confederate groups and individuals?

JW: It was incredibly real. Between the riders and the fighters and men like John Mosby, Nathan Bedford Forrest, the legendary William Quantrill, and the James boys, it would have been possible to carry out guerrilla war, not only for days, but for weeks, if not for years.

SG: At the end of your chapter titled “Reconciliation,” you tell a moving story of an incident at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. Please repeat that story for our readers.

JW: The marvelous anchor of ABC news, Peter Jennings, told me that, when he read the scene, it caused tears to form. But I want to give a little bit of setting just for a second. One thing that Robert E. Lee did after the war was to give an interview to the New York Herald Tribune. In this interview, he said the best men of the South were rejoicing at the end of the slavery, and he talked about what we in the United States should do next. The reason that this statement is so significant is that in earlier days when he said “we,” he always meant the Confederacy. Now he said “we” in the context of what the country should do next. The moving scene at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond occurred during the service when a black man walked to the chancel rail to take communion. Members of the congregation were unsure as to what would happen next. All of a sudden, an elderly man who looked sickly made his way up to the rail and took communion next to that black man. That man was Robert E. Lee.

SG: Such disparate individuals as President George W. Bush and actor Tom Hanks read and reacted to April 1865. Please comment on their reactions.

JW: This book really has had a remarkable set of individuals who have read it: President George Bush and President George Herbert Walker Bush; Bill Clinton; Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts; many senators, including Mitch McConnell; and the legendary actor Tom Hanks. In George Bush’s case, he read the book and finished it the day after 9/11 and was observed carrying the book as he exited Marine 1 on the south lawn of the White House on September 12, 2001. Tom Hanks gave an interview to Maureen Dowd, a great journalist of the New York Times. At one point, he went into his library and he came out with April 1865 and said that this book was amazing.

SG: Do you have an upcoming project which you can share with our readers?

JW: I’m not at a point where I’m yet ready to share with your readers, but I can give one little inkling into what I’m doing. In each of my books, I try to find a profound turning point in time. I try to write about a significant president as well. I try to write about something fresh. So while I’m not at liberty yet to tell you what I’m writing about, you might think about what I’ve written before: George Washington in his era; Lincoln in his era; and FDR in his era. In each of these are momentous periods and momentous presidents. So I’m hoping to do the same with my next book and all I can say is: “stay tuned.”

Jay Winik is the author of April 1865: The Month that Saved America. He will give the annual R. Gerald McMurtry Lecture at the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on September 16, 2019.