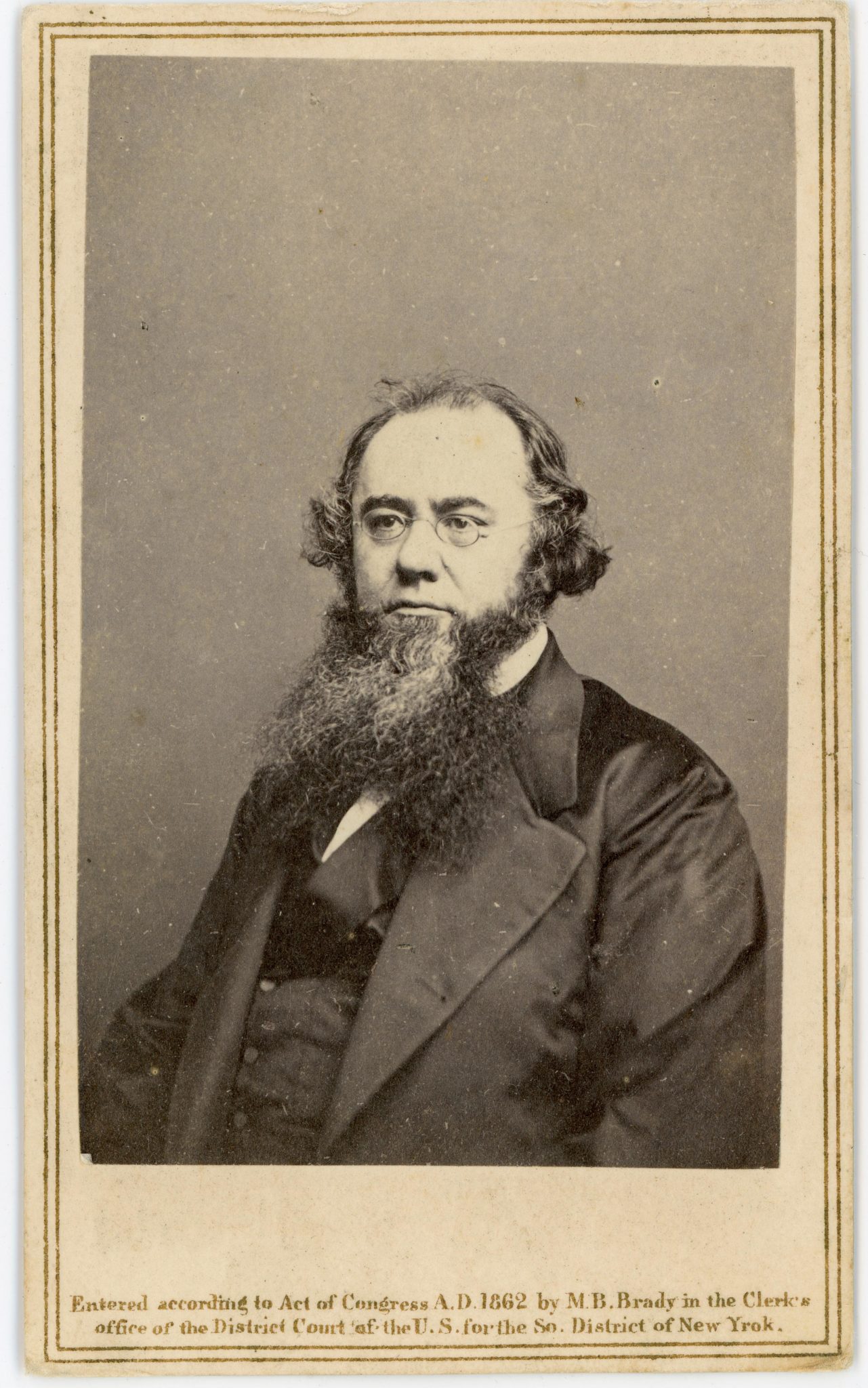

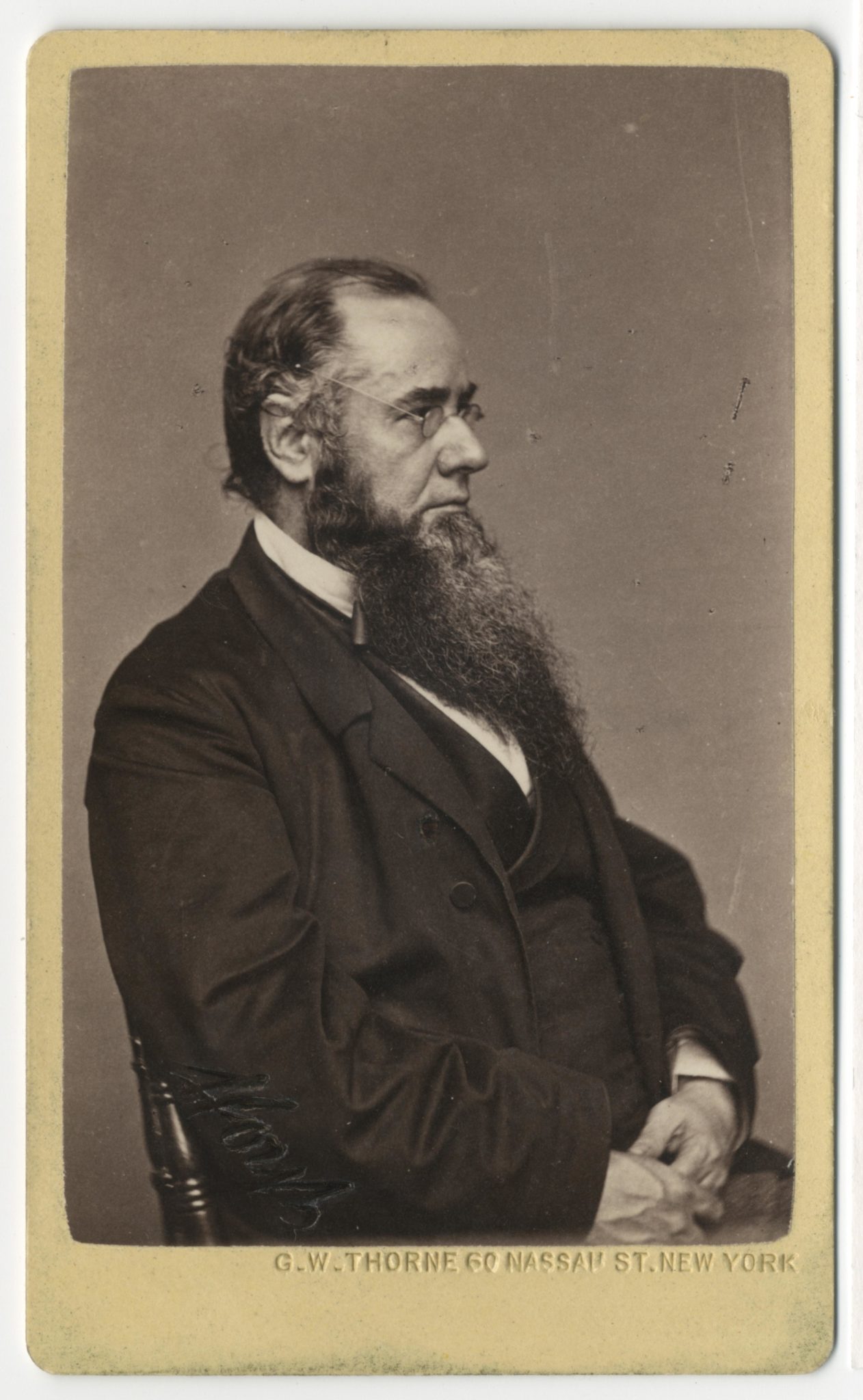

Edwin McMasters Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton by Frank J. Williams

Edwin McMasters Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, on December 19, 1814. On the eve of achieving his life’s dream, chronic asthma caused his death on December 24, 1869. His lifelong struggle with poor health also contributed to his volatile temper, as did the early loss of his father and the deaths of his brother and two children. Upon his father’s death, young Stanton had to take work at a bookstore to support his mother. He became a lawyer in 1836 and married Mary A. Lamson, with whom he had two children.

Judge Benjamin Tappan, a family friend, invited Stanton to join his law firm in 1837. Tappan, a Democrat with anti-slavery leanings, mentored Stanton and provided the base for Stanton’s political direction. In 1837, Stanton was elected prosecuting attorney for Harrison County, Ohio. He also played a major role in the election of his partner to a U.S. Senate seat.

After Mary died in 1844, Stanton sank into deep depression. Obsessed by work, Stanton expanded his law practice, and he left Tappan in 1845. In 1847, he partnered with Charles Shaler, and he soon had clients throughout Ohio and Pennsylvania. Stanton was extremely bright, shrewd, and aggressive and was soon regarded as one of the best trial lawyers in the country. Helen Hutchinson entered Stanton’s life, and they married in 1856. They had four children.

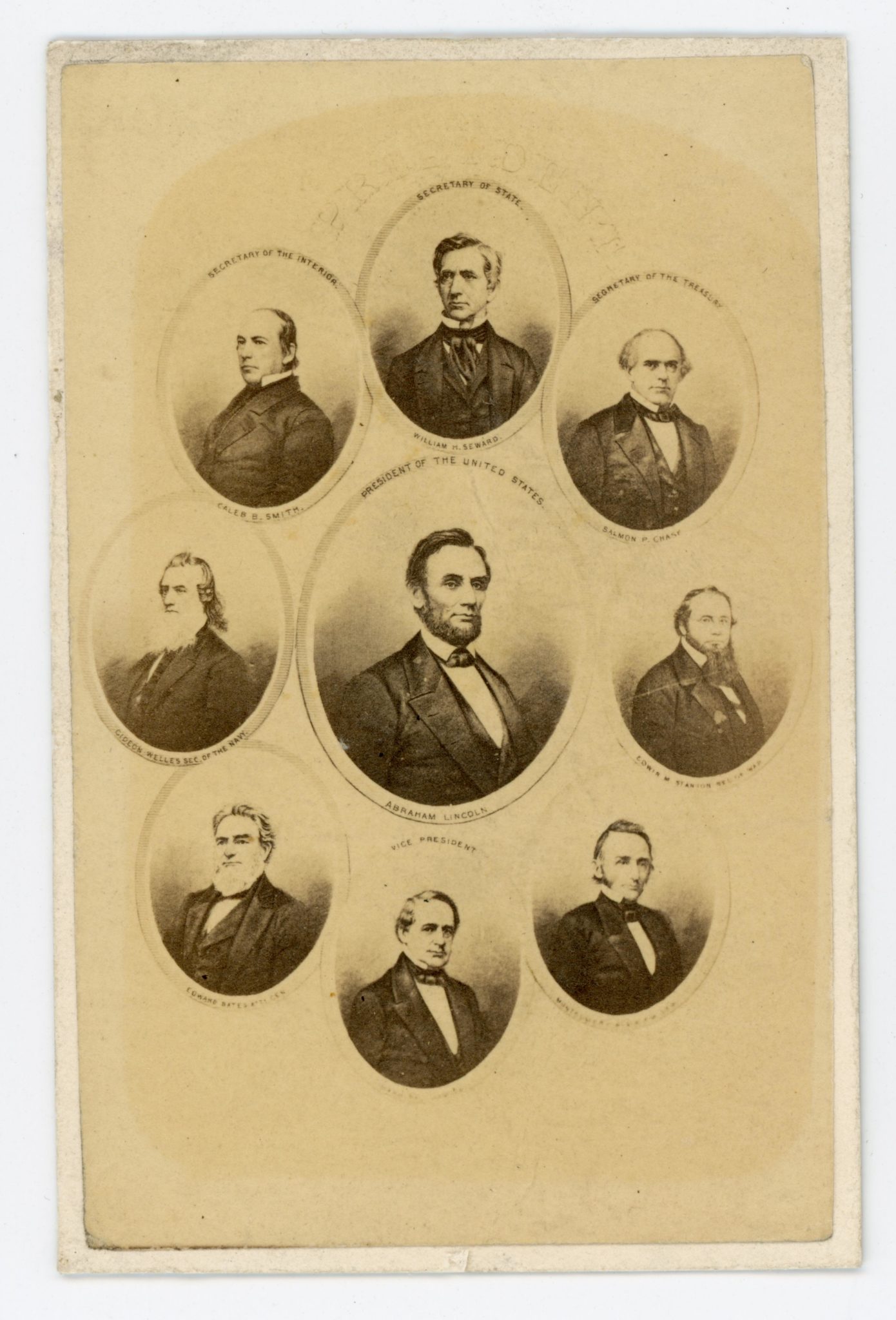

After moving to Washington in 1856, Stanton began arguing cases before the Supreme Court of the United States. Forming a close friendship with Attorney General Jeremiah S. Black, who served under President James Buchanan, Stanton supported Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge for the presidency in 1860 because he believed that only Breckinridge could save the Union. After Lincoln was elected in November, Buchanan appointed Black to serve as secretary of state, and Stanton became his successor as attorney general. Stanton supported the Union and did all that he could to prevent secession. He and Black pressured Buchanan to push back against the secessionist elements in the South. Stanton also back-doored intelligence to the incoming secretary of state, William H. Seward.

Stanton greeted Abraham Lincoln’s arrival in Washington as president-elect with contempt. After Lincoln was inaugurated the 16th president on March 4, 1861, Stanton remained in Washington where he became a consultant to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. In December 1861, he helped Cameron draft a report that recommended enlistment of African-American troops. When Cameron was compelled to resign due to his mismanagement and corruption of contracts in the War Department, Lincoln named Stanton as Cameron’s replacement. It’s uncertain why Lincoln made this appointment, as Stanton was a Democrat and Lincoln had been insulted by Stanton in a patent case while Lincoln was the local counsel in Illinois. But Seward, who thought Stanton was a moderate, had recommended him. And Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase, an abolitionist, was impressed with Stanton’s anti-slavery views.

Stanton was a much better manager than his predecessor Cameron. Working well with leaders of both parties, he made efforts to cultivate relationships in Congress, especially with those who had a major say on military appropriations bills. He reorganized the War Department and reformed the guidelines by which the department conducted business, establishing a system of open, competitive bidding for contracts. He also assumed control of the Union’s railroad system and telegraph network. He eventually befriended Major General George B. McClellan, the new Commander of the Army of the Potomac, who had replaced General Winfield Scott as commander in chief of the army. But after McClellan’s repeated failures to take aggressive action, Stanton asked Lincoln to remove McClellan from command of all the Union armies, and Lincoln complied, leaving the general in command of only the Army of the Potomac. McClellan, true to his insecurity and failures as a battlefield commander, blamed Stanton. They then became bitter enemies until McClellan was finally relieved of all command by President Lincoln after the Battle of Antietam in the fall of 1862.

The Lincoln-Stanton relationship evolved into mutual respect, despite Stanton’s initial low opinion of Lincoln as a lawyer and as a president. While the two often disagreed, the president was able to soften the war secretary’s harsh demeanor and draw him out of his self-absorption. They became close friends. To Lincoln, Stanton became his “no” man, turning down outrageous demands of the president’s time from those seeking government contracts and patronage.

Between late 1862 and 1864, Stanton played a central role in Lincoln’s administration, especially in the appointment and removal of military commanders. He oversaw military operations and, along with Lincoln, played a role in shaping Union strategy. He was an advocate of total war and, like Lincoln, supported the confiscation of slaves and other property of secessionists as a war measure, believing that the federal government could seize the slaves and free them because they were considered property by the slaveholding South. He therefore strongly supported Lincoln’s issuance of the preliminary and final Emancipation Proclamations and urged inclusion of the call for enlistment of African-American troops in the final proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Stanton’s most controversial function during this period was to supervise internal security, a duty that he assumed from Secretary of State William H. Seward in March 1862. Initially, Stanton restricted the exercise of martial law and ordered the release of most of the citizens interned under Seward after Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus. Bitter objections to conscription – the first draft in American history – as well as the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation caused the administration to broaden the suspension of habeas corpus nationwide, and military arrests rose dramatically. In March 1863, Congress established a militarized provost marshal’s bureau that was placed under Stanton’s control. This created, in effect, a national police force. Stanton used this apparatus vigorously to enforce the draft and combat dissent, including the arrest and detention of civilians and their trial before a military commission (there were over 4,200 U.S. citizens tried before these tribunals), as well as closure of disloyal newspapers. But he did support General in Chief Halleck’s collaboration with Columbia University Professor Francis Lieber, who drafted the first code on the law of war. President Lincoln approved the code, and it became General Order 100 in 1863. (It would become the basis for the first Hague Conventions in 1899 and 1907.)

Because his supporters were now primarily Republicans and like the trial lawyer he once was, Stanton did not hesitate to seek Republican support for military appropriations. His position on soldiers voting in the canvas of 1864 helped the Republicans and President Lincoln achieve victory. This was the first soldier vote, and it permitted voting in the field.

With the appointment in early 1864 of Ulysses S. Grant as general in chief, President Lincoln, almost unbeknownst to himself, created the first effective joint chiefs of command structure with General in Chief Grant, Army Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck, and the president as commander in chief. With Stanton providing logistics through the War Department, the armies were provided the tools to wage war. Lincoln provided overall direction, and his acuity as a politician helped assure a successful political strategy. Halleck acted as a conduit between the president and secretary of war to Grant and other military departments.

Stanton’s relations with Grant’s colleague and friend, General William T. Sherman, were less cordial, especially when Sherman gave more generous terms to the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s army than those Grant gave at Appomattox. Stanton revoked the order. Because Sherman felt he was following Grant’s lead, Stanton’s action upset him. They would remain enemies for the rest of their lives.

The assassination of President Lincoln on April 9, 1865, enraged Stanton. Grieving at Lincoln’s deathbed, he allegedly said, “He now belongs to the ages,” which somehow morphed into, “Now he belongs to the angels.” (Stanton biographer Walter Stahr believes the secretary of war uttered nothing when Lincoln breathed his last.) After the assassination, a furious Stanton assumed control of the government and used all his resources to hunt down the conspirators who had orchestrated this crime and the attack on Secretary of State Seward. He pressed President Andrew Johnson and Attorney General James Speed for a military commission to try the conspirators and personally directed the prosecution, using Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt and Congressman John Bingham as his surrogates. The judge advocate general and the congressman actually joined in the deliberations of the members of the military commission that tried the conspirators. Stanton favored the death penalty for the convicted conspirators, including Mary Surratt, the proprietor of the boarding house where the plotting had transpired. It is unfounded that Stanton withheld the recommendation of the military court for clemency in Surratt’s case, nor was he himself involved in the conspiracy as some have alleged.

Stanton remained secretary of war under President Johnson, so he was actively involved in Reconstruction and overseeing the demobilization of the Union armies. Reports of violence against freedmen changed Stanton’s view of Johnson’s policy of lenient Reconstruction. Stanton came to believe in stronger measures. Working with Grant, he tried to convince the president to accept the more Radical view of Reconstruction by Congress.

Stanton and Grant began an alliance with Congress because of the failure of Johnson’s policies. Stanton supported the first and second Reconstruction Acts despite opposition from the president. There was to be no compromise with the president, and Johnson turned against him. Stanton and Grant drafted a third Reconstruction Act that removed the armies in the South from the president’s control.

Johnson demanded Stanton’s resignation. Stanton refused, and on August 11, 1867, Johnson suspended him and named Grant as his successor ad interim. Congress in January 1868 ordered Stanton restored to his office under the terms of the Tenure of Office Act, which Congress had passed over Johnson’s veto in March 1867 to protect Republicans in the cabinet, including Stanton himself. Grant immediately acquiesced, and Stanton resumed his duties. Johnson again tried to replace Stanton, this time with General Lorenzo Thomas, but Stanton refused to acknowledge the appointment by blockading himself in his office. On February 22, 1868, the House of Representatives drafted articles of impeachment against President Johnson on charges of violating the Tenure of Office Act. Johnson was acquitted by one vote in the Senate.

Disappointed that the Senate was unable to convict Johnson, Stanton remained in his post. But on May 26, 1868, he resigned and was replaced by General John M. Schofield. Stanton returned to private life, exhausted, in ill health, and virtually bankrupt. He did, however, participate in the campaign to elect Ulysses S. Grant president in November 1868. Grant was elected, but Stanton’s health had suffered another setback from his active support of General Grant.

Grant appointed Stanton to a vacant seat on the Supreme Court out of gratitude and for his years of friendship and service. Although the Senate ratified the appointment, Stanton’s asthma finally took his life at the age of fifty-five, before he could take the oath.

Stanton was one of the central and most controversial political figures in the Civil War era. Lincoln referred to him as his “Mars” – the chief manager under the president in the Union’s war effort. Stanton engendered intense hostility because of his abrasive personality, his autocratic leadership style, and his position as director of internal security, which inevitably made him a lightning rod for dissent. Yet his efforts did much to redeem the sacrifices of the war.

Suggested reading:

Walter Stahr, Stanton: Lincoln’s War Secretary (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017)

William Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

Frank J. Williams is Founding Chair of the Lincoln Forum and serves as President of the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library and Museum at Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS